by Evropa Soberana

Antiquity

With the de-barbarization that ensued after the emergence of a sedentary lifestyle, the people soon realised that a society uprooted from Nature immediately degenerates. In short, humanity woke up to the dangers of civilisation.

To compensate for it, the leaders of these societies set up processes aimed at counteracting the pernicious effects of the greatest cancer that humanity has suffered: dysgenics, that is, the degeneration of the race that results from the absence of natural selection.

Here we will see that, in many civilised societies of antiquity, the laws of Nature were automatically followed. Its leaders intervened consciously and voluntarily to stop human reproduction and allow reproduction only to the best, so that the species did not degenerate. As Madison Grant wrote, where the environment is too soft and luxurious and it is not necessary to fight to survive, not only weak individuals are allowed to live. Strong types also gain weight mentally and physically!

The most illustrative examples of this era are Hindus, Greeks (among these the Spartans) and Romans. The Hellenic ideal of the kalokagathia, that is to say, an association of goodness-beauty—achieved by maintaining the purity of blood within the framework of a process of selection of the best—laid the foundations to everything that in the West has been considered ‘classical’ and ‘beautiful’ since then until recently.

The most illustrative examples of this era are Hindus, Greeks (among these the Spartans) and Romans. The Hellenic ideal of the kalokagathia, that is to say, an association of goodness-beauty—achieved by maintaining the purity of blood within the framework of a process of selection of the best—laid the foundations to everything that in the West has been considered ‘classical’ and ‘beautiful’ since then until recently.

In another long essay we have seen that the art that has come to us from European antiquity is perhaps only two percent of what existed and, to top it off, probably the least interesting and sublime: primitive Christians destroyed almost every legacy Greco-Roman civilisation. No one can know how many philosophers and authors suffered total destruction of their works, without anyone knowing again who they were or what they thought; and many other classic writings were censored, adulterated, corrected or mutilated.

However, we have at least some spoils of the pre-Christian era. Although ninety-eight percent of classical art was destroyed by the early Christians, what survived speaks for itself as a tribute to the selection, balance, health and excellence of all human qualities.

However, we have at least some spoils of the pre-Christian era. Although ninety-eight percent of classical art was destroyed by the early Christians, what survived speaks for itself as a tribute to the selection, balance, health and excellence of all human qualities.

The Hindus. The Indo-European (i.e., Nordic) invaders arrived in India around 1400 BCE and immediately placed measures to favour high birth rates of the best elements of the population, identified with the Aryan invaders, and the decline of the worst, identified with the Negroid-Dravidic stratum.

The entire caste system was a great eugenics process in which the chandala (a term also used by Nietzsche to define the morals of Jews and Christians), the outcast, the untouchable, the sinful caste, the one considered inferior, was subjected to a horrendous lifestyle: using only the clothes of the dead bodies, drink only water from stagnant areas or animal tracks, not allow their women to be attended during childbirth, prohibition of washing, work as executioners, burials and latrine cleaners, and an unpleasant etcetera. Such impositions favoured that diseases were endemic among them; they fell like flies so that their numbers never constituted a danger for the best.

We are therefore faced with an example of negative eugenics: limiting the procreation of the worst. These measures are included in the Laws of Manu, the legendary Indo-Aryan legislator who laid the foundations for caste hierarchy. According to scientist Theodosius Dobzhansky, a renowned Ukrainian geneticist, ‘The caste system of India has been the greatest genetic experiment ever conducted by man’ (Genetic Diversity and Human Equality).

A woman always gives the world a child endowed with the same qualities as the one who has fathered him… A man of abject birth takes the natural evil of his father or his mother, or both at the same time, and can never hide its origin (Law of Manu, Book X).

Lycurgus (8th century BCE), a regent of Sparta, travelled through Spain, Egypt and India accumulating wisdom and, later, carrying out a revolution in Sparta after which the polis would militarize and establish a social system based on eugenics. The measures of this program highlight the infanticides of deformed, ugly or stupid newborns. Broadly speaking, Lycurgus’s policy was based on training perfect human beings that gave birth to perfect human beings, and there was no place for genetic engenders in that plan. On the other hand, the crypteia, carried out by the Spartan authorities on the helots (the submissive plebs) can perfectly be considered a very brutal and primitive example of negative eugenics.

Lycurgus (8th century BCE), a regent of Sparta, travelled through Spain, Egypt and India accumulating wisdom and, later, carrying out a revolution in Sparta after which the polis would militarize and establish a social system based on eugenics. The measures of this program highlight the infanticides of deformed, ugly or stupid newborns. Broadly speaking, Lycurgus’s policy was based on training perfect human beings that gave birth to perfect human beings, and there was no place for genetic engenders in that plan. On the other hand, the crypteia, carried out by the Spartan authorities on the helots (the submissive plebs) can perfectly be considered a very brutal and primitive example of negative eugenics.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: Having helots as slaves was a fatal flaw for Spartan civilisation. The laws of Lycurgus did not foresee that eugenic customs would fatally relax after a catastrophic war (as would happen after the Peloponnesian War). A real solution would have been, as William Pierce saw in his study on Greece, to exterminate the non-Nordic Mediterraneans of Sparta and extend such policy to all Greece, and eventually to all Europe.

______ 卐 ______

As for the Spartan policies of positive eugenics—favouring the multiplication of the best—we see popular rituals such as the coronation of a male champion and a female champion in a sports competition, or a king and queen in a beauty pageant, or tax exemption to the citizens who left four children. The best were expected to marry the best. Single people over twenty-five years old were extremely frowned upon and punished with fines and humiliating acts.

If the parents are strong, the children will be strong (Fr. 7).

Heraclitus (535-484 BCE), a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher known for his aphorisms in the style of the Oracle of Delphi. He established that wisdom was much more than a mere accumulation of knowledge and intelligence, also valuing intuition, instinct and will. He said: ‘I ask all mortals to father well-born children of noble parents’.

Leonidas (dies in 480 BCE), King of Sparta and supreme commander of the Greek troops in the Battle of Thermopylae. He fought in numerical inferiority against the Persians until the end, giving time for the evacuation of Greek cities, granting margin for an Athenian victory in the battle of Salamis and laying the foundations of the definitive Persian defeat in Plataea. Leonidas and his Spartans are an example of heroism, dedication to their people, a spirit of sacrifice, training and honour for all Western armies of all time.

Leonidas (dies in 480 BCE), King of Sparta and supreme commander of the Greek troops in the Battle of Thermopylae. He fought in numerical inferiority against the Persians until the end, giving time for the evacuation of Greek cities, granting margin for an Athenian victory in the battle of Salamis and laying the foundations of the definitive Persian defeat in Plataea. Leonidas and his Spartans are an example of heroism, dedication to their people, a spirit of sacrifice, training and honour for all Western armies of all time.

Marry the capable and give birth to the capable! (exhortation to the Spartan people before leaving for the Thermopylae according to Plutarch, On the Malice of Herodotus, 32).

Theognis of Megara (6th century BCE) was one of the great Greek poets. He has bequeathed us in his Theognidea a series of interesting reflections and advice to his disciple Cyrnus. Among other things, Theognis divides the population into ‘good’—the nobility, identified with the Hellenic invaders—and ‘bad’—the native plebeian population of Greece, which progressively accumulated money and rights:

In rams and asses and horses, Cyrnus, we seek

the thoroughbred, and a man is concerned therein

to get him offspring of good stock;

Yet in marriage a good man thinketh not twice of wedding

the bad daughter of a bad sire if the father give him many possessions;

Nor doth a woman disdain the bed of a bad man if he be wealthy,

but is fain rather to be rich than to be good.

For ’tis possessions they prize;

and a good man weddeth of bad stock and a bad man of good;

race is confounded of riches.

In like manner, son of Polypaus,

marvel thou not that the race of thy townsmen is made obscure;

’tis because bad things are mingled with good.

Even he that knoweth her to be such, weddeth a low-born woman for pelf,

albeit he be of good repute and she of ill;

for he is urged by strong Necessity, who giveth a man hardihood.

Critias (460-403 BCE), Athenian philosopher, speaker, teacher, poet and uncle of Plato. He is known for being part of the Spartan occupation government known as the thirty tyrants. We will appreciate the importance that this man attached not only to inheritance, but to sports training without which a human being will never be complete.

I begin with the birth of a man, demonstrating how he can be the best and strongest in the body if his father trains and endures hardness, and if his future mother is strong and also trains.

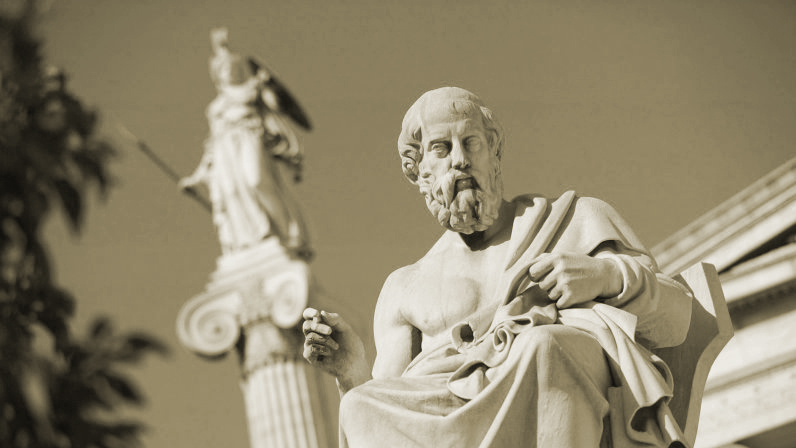

Plato (428-347 BCE), probably the most famous philosopher of all time, was inspired by Sparta to propose the measures of Greek regeneration in his work The Republic, plagued with values of both positive eugenics—promoting the best—as negative eugenics—limit the worst—, especially with regard to the caste of the ‘guardians’. Plato, like most Greek philosophers, was in favour of exposing defective children to the weather so that they died.

Plato (428-347 BCE), probably the most famous philosopher of all time, was inspired by Sparta to propose the measures of Greek regeneration in his work The Republic, plagued with values of both positive eugenics—promoting the best—as negative eugenics—limit the worst—, especially with regard to the caste of the ‘guardians’. Plato, like most Greek philosophers, was in favour of exposing defective children to the weather so that they died.

It is necessary, according to our principles, that the relationships of the most outstanding individuals of one sex or the other are very frequent, and those of the lower individuals very rare. In addition, it is necessary to raise the children of the first and not of the second, if you want the flock to not degenerate (The Republic).

Based on what was agreed, it is necessary for the best men to join the best women as often as possible, and on the contrary, the worst with the worst; and the offspring of the best and not the worst should be raised, so our flock will become excellent (Statesman, 459).

That even better children are born from elite men, and from useful men to the country, even more useful children (Statesman, 461).

Xenophon (430-354), soldier, accomplished horseman during the Peloponnesian war, mercenary in the heart of Persia during the expedition of the ten thousand, philosopher, pro-Spartan and historian. Notorious anti-democrat who abhorred the Athenian government, he longed for fairer forms of government such as those he met in Persia and Sparta, where he sent his children to be educated. Together with Plutarch, Xenophon is the greatest source of information about Sparta, admiring the eugenic practices established by Lycurgus.

Xenophon (430-354), soldier, accomplished horseman during the Peloponnesian war, mercenary in the heart of Persia during the expedition of the ten thousand, philosopher, pro-Spartan and historian. Notorious anti-democrat who abhorred the Athenian government, he longed for fairer forms of government such as those he met in Persia and Sparta, where he sent his children to be educated. Together with Plutarch, Xenophon is the greatest source of information about Sparta, admiring the eugenic practices established by Lycurgus.

[Lycurgus] considered that the production of children was the noblest duty of free citizens (Constitution of the Lacedaemonians).

An old man had to introduce his wife to a young man in the prime of life whom he admired for his qualities, to have children with him (Constitution of the Lacedaemonians).

Isocrates (436-338 BCE), politician, philosopher and Greek teacher, was one of the famous ten Attic speakers and probably the most influential rhetorician of his time. He founded a public speaking school that became famous for its effectiveness and criticised the politics of many Greek cities, which instead of stimulating their birth rate inflated their numbers through the mass immigration of slaves, which he considered inferior to the Hellenic population. In this quotation it is verified to what extent Isocrates valued quality versus quantity:

It should not be said as happy that city which, from all extremes, randomly accumulates many citizens; but the one that best preserves the race of the settled since the beginning.

Euripides (480-406 BCE), playwright, a friend of Socrates and undoubtedly one of the greatest poets of all antiquity; his stain was an excessive machismo that led him to criticise the greater freedom enjoyed by women in Sparta. Disappointed and disgusted by the policies of a decadent Greece he retired to Macedonia, a place where Hellenic traditions were still pure, where he finally died.

Euripides (480-406 BCE), playwright, a friend of Socrates and undoubtedly one of the greatest poets of all antiquity; his stain was an excessive machismo that led him to criticise the greater freedom enjoyed by women in Sparta. Disappointed and disgusted by the policies of a decadent Greece he retired to Macedonia, a place where Hellenic traditions were still pure, where he finally died.

There is no more precious treasure for children than to be born of a noble and virtuous father and to marry among noble families. Curse to the reckless who, defeated by passion, joins the unworthy and leaves his children to dishonour in return for guilty pleasures (Heracleidae).

Aristotle (384-322 BCE), the famous philosopher who educated Alexander the Great and laid the western foundations of Hellenism, logic and sciences such as biology, taxonomy and zoology. Aristotle extends extensively in his work Politeia on the problems posed by eugenics, birth control, childhood feeding and education (books VII and VIII). He generally admired the ancient Spartan system, with some reservations—in my opinion unfounded as Sparta was not decadent—because the ephorate was tyrannical.

Aristotle (384-322 BCE), the famous philosopher who educated Alexander the Great and laid the western foundations of Hellenism, logic and sciences such as biology, taxonomy and zoology. Aristotle extends extensively in his work Politeia on the problems posed by eugenics, birth control, childhood feeding and education (books VII and VIII). He generally admired the ancient Spartan system, with some reservations—in my opinion unfounded as Sparta was not decadent—because the ephorate was tyrannical.

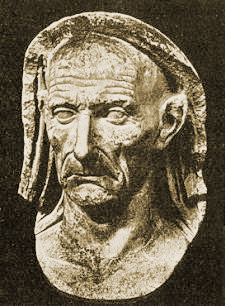

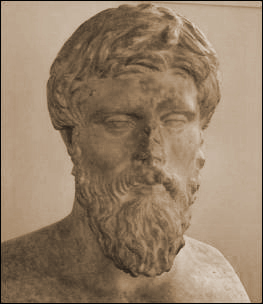

(Left, a Patrician bust.) The Patricians were the Roman leaders in the early days, when Rome was a Republic. These men were the patriarchs or clan chiefs of each of the thirty noble families descended from Italic invaders, and they ran all Roman institutions including the legions, the courts and the Senate. Sober, pure, ascetic and hard, their people held them in high regard as repositories of the highest wisdom and Roman posterity honoured them as gods.

(Left, a Patrician bust.) The Patricians were the Roman leaders in the early days, when Rome was a Republic. These men were the patriarchs or clan chiefs of each of the thirty noble families descended from Italic invaders, and they ran all Roman institutions including the legions, the courts and the Senate. Sober, pure, ascetic and hard, their people held them in high regard as repositories of the highest wisdom and Roman posterity honoured them as gods.

Their descendants formed the Patricians, the later Roman aristocracy, which gradually decayed throughout the Empire until almost completely dissolving, turning Rome into a disgusting decadent monster that deserved to be razed. After the Punic wars and Julius Caesar, Rome largely lost its Indo-European spirit.

In the IV of the XII tablets of the law, it was established that deformed children must be killed at birth. It was also left to the patriarchs of the patrician clans to decide which were the unfit children. They were usually drowned in the waters of the Tiber River, and other times abandoned, exposing them to wild animals and elements in a process called exposure. Apparently, the Romans did not fare so badly with this purifying tactic as we see in their conquering history.

Distorium vultum sequitur distortio morum, ‘A crooked face follows a crooked moral’—Roman proverb.

Meleager of Gadara (1st century BCE), Greek epigram compiler within the Hellenistic stage, who wrote: ‘If one mixes good with bad, a good progeny would not be born, but if both parents are good, they will beget noble children’ (Fr. 9).

Horace (65 BCE-8 CE) said: ‘The virtue of parents is a great dowry’ and ‘’The good and the brave descend from the good and the brave’ (Odes, IV, 4, 29).

Seneca (4 BCE-65 CE), Roman philosopher of the Stoic school (the same school that Marcus Aurelius and Julian the Apostate belonged), of Hispanic-Celtic origin and teacher of Emperor Nero.

Seneca (4 BCE-65 CE), Roman philosopher of the Stoic school (the same school that Marcus Aurelius and Julian the Apostate belonged), of Hispanic-Celtic origin and teacher of Emperor Nero.

We exterminate hydrophobic dogs; we kill the indomitable bulls; we slaughter sick sheep for fear that they infest the flock; we suffocate the monstrous foetuses and even drown the children if they are weak and deformed. It is not passion, but reason, to separate healthy parts from those that can corrupt them (Of Anger, XV).

Plutarch (45-120 CE). Philosopher, mathematician, historian, speaker and priest of Apollo at the Oracle of Delphi. It is also one of the important sources of information about Sparta in his books Ancient Customs of the Lacedaemonians and Life of Lycurgus.

Plutarch (45-120 CE). Philosopher, mathematician, historian, speaker and priest of Apollo at the Oracle of Delphi. It is also one of the important sources of information about Sparta in his books Ancient Customs of the Lacedaemonians and Life of Lycurgus.

Leaving a being who is not healthy and strong from the beginning is not beneficial for the State or for the individual himself (Ancient Customs of the Lacedaemonians).

When a baby was born he was taken to a council of elders to be examined. If the baby was defective in some way the elders threw him down a ravine. Such a baby, in the opinion of the Spartans, should not be allowed to live (Life of Lycurgus).