by Laurent Guyénot

The Old Testament as Israel’s Trojan Horse

In pre-Christian times, pagan scholars had shown little interest in the Hebrew Bible. Jewish writers (Aristobulus of Paneas, Artapan of Alexandria) had tried to bluff the Greeks on the antiquity of the Torah, claiming that Homer, Hesiod, Pythagoras, Socrates and Plato had been inspired by Moses, but no one before the Church Fathers seems to have taken them seriously. Jews had even produced fake Greek prophecies of their success under the title Sibylline Oracles, and written under a Greek pseudonym a Letter of Aristea to Philocrates praising Judaism, but again, it was not until the triumph of Christianity that these texts were met with Gentile gullibility.

In pre-Christian times, pagan scholars had shown little interest in the Hebrew Bible. Jewish writers (Aristobulus of Paneas, Artapan of Alexandria) had tried to bluff the Greeks on the antiquity of the Torah, claiming that Homer, Hesiod, Pythagoras, Socrates and Plato had been inspired by Moses, but no one before the Church Fathers seems to have taken them seriously. Jews had even produced fake Greek prophecies of their success under the title Sibylline Oracles, and written under a Greek pseudonym a Letter of Aristea to Philocrates praising Judaism, but again, it was not until the triumph of Christianity that these texts were met with Gentile gullibility.

Thanks to Christianity, the Jewish Tanakh was elevated to the status of authoritative history, and Jewish authors writing for pagans, such as Josephus and Philo, gained undeserved reputation—while being ignored by rabbinic Judaism. Christian academia uncritically tuned to the rigged history of the Jews. While Herodotus had crossed Syria-Palestine around 450 BCE without hearing about Judeans or Israelites, Christian historians decided that Jerusalem had been at that time the center of the world, and accepted as fact the totally fictitious empire of Solomon. Until the 19th century, world history was calibrated on a largely fanciful biblical chronology (Egyptology is now trying to recover from it).[4]

It can be argued, of course, that the Old Testament has served Christendom well: it was certainly not in the nonviolence of Christ that the Catholic Church found the energy and ideological means to impose its world order for nearly a thousand years on Western Europe. Yet for this glorious past, there was obviously a price to pay, a debt to the Jews that has to be paid one way or another. It is as if Christianity has sold its soul to the god of Israel, in exchange for its great accomplishment.

The Church has always advertised itself to the Jews as the gateway out of the prison of the Law, into the freedom of Christ. But it has never requested Jewish converts to leave their Torah on the doorstep. The Jews who entered the Church entered with their Bible, that is to say, with a big part of their Jewishness, while freeing themselves from all the civil restrictions imposed on their non-converted brethren.

When Jews were judged too slow to convert willingly, they were sometimes forced into baptism under threats of expulsion or death. The first documented case goes back to Clovis’ grandson, according to Bishop Gregory of Tours:

King Chilperic commanded that a large number of Jews be baptized, and he himself held several on the fonts. But many were baptized only in body and not in heart; they soon returned to their deceitful habits, for they really kept the Sabbath, and pretended to honour the Sunday (History of the Franks, chapter V).

Such collective forced conversions, producing only insincere and resentful Christians, were conducted throughout the Middle Ages. Hundreds of thousands of Spanish and Portuguese Jews were forced to convert at the end of the 15th century, before emigrating throughout Europe. Many of these ‘New Christians’ not only continued to ‘Judaize’ among themselves, but could now have greater influence on the ‘Old Christians’. The penetration of the Jewish spirit into the Roman Church, under the influence of these reluctantly converted Jews and their descendants, is a much more massive phenomenon than is generally admitted.

One case in point is the Jesuit Order, whose foundation coincided with the peak of the Spanish repression against Marranos, with the 1547 ‘purity-of-blood’ legislation issued by the Archbishop of Toledo and Inquisitor General of Spain. Of the seven founding members, four at least were of Jewish ancestry. The case of Loyola himself is unclear, but he was noted for his strong philo-Semitism. Robert Markys has demonstrated, in a groundbreaking study, how crypto-Jews infiltrated key positions in the Jesuit Order from its very beginning, resorting to nepotism in order to eventually establish a monopoly on top positions that extended to the Vatican. King Phillip II of Spain called the Order a ‘Synagogue of Hebrews.’[5]

Marranos established in the Spanish Netherlands played an important role in the Calvinist movement. According to Jewish historian Lucien Wolf,

The Marranos in Antwerp had taken an active part in the Reformation movement, and had given up their mask of Catholicism for a not less hollow pretense of Calvinism… The simulation of Calvinism brought them new friends, who, like them, were enemies of Rome, Spain and the Inquisition… Moreover, it was a form of Christianity which came nearer to their own simple Judaism.[6]

Calvin himself had learned Hebrew from rabbis and heaped praise on the Jewish people. He wrote in his commentary on Psalm 119: ‘Where did Our Lord Jesus Christ and his apostles draw their doctrine, if not Moses? And when we peel off all the layers, we find that the Gospel is simply an exhibition of what Moses had already said.’ The Covenant of God with the Jewish people is irrevocable because ‘no promise of God can be undone.’ That Covenant, ‘in its substance and truth, is so similar to ours, that we can call them one. The only difference is the order in which they were given.’[7]

Within one century, Calvinism, or Puritanism, became a dominant cultural and political force in England. Jewish historian Cecil Roth explains:

The religious developments of the seventeenth century brought to its climax an unmistakable philo-semitic tendency in certain English circles. Puritanism represented above all a return to the Bible, and this automatically fostered a more favourable frame of mind towards the people of the Old Testament.[8]

Some British Puritans went so far as to consider the Leviticus as still in force; they circumcised their children and scrupulously respected the Sabbath. Under Charles I (1625–1649), wrote Isaac d’Israeli (father of Benjamin Disraeli), ‘it seemed that religion chiefly consisted of Sabbatarian rigours; and that a British senate had been transformed into a company of Hebrew Rabbis.’[9] Wealthy Jews started to marry their daughters into the British aristocracy, to the extent that, according to Hilaire Belloc’s estimate, ‘with the opening of the twentieth century those of the great territorial English families in which there was no Jewish blood were the exception.’[10]

The influence of Puritanism on many aspects of British society naturally extended to the United States. The national mythology of the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ fleeing Egypt (Anglican England) and settling into the Promised Land as the new chosen people, sets the tone. However, the Judaization of American Christianity has not been a spontaneous process from within, but rather one controlled by skillful manipulations from outside. For the 19th century, a good example is the Scofield Reference Bible, published in 1909 by Oxford University Press, under the sponsorship of Samuel Untermeyer, a Wall Street lawyer, Federal Reserve co-founder, and devoted Zionist, who would become the herald of the ‘holy war’ against Germany in 1933. The Scofield Bible is loaded with highly tendentious footnotes. For example, Yahweh’s promise to Abraham in Genesis 12:1-3 gets a two-thirds-page footnote explaining that ‘God made an unconditional promise of blessings through Abram’s seed to the nation of Israel to inherit a specific territory forever’ (although Jacob, who first received the name Israel, was not yet born). The same note explains that ‘Both OT and NT are full of post-Sinaitic promises concerning Israel and the land which is to be Israel’s everlasting possession,’ accompanied by ‘a curse laid upon those who persecute the Jews,’ or ‘commit the sin of anti-Semitism.’[11]

As a result of this kind of gross propaganda, most American Evangelicals regard the creation of Israel in 1948 and its military victory in 1967 as miracles fulfilling biblical prophecies and heralding the second coming of Christ. Jerry Falwell declared, ‘Right at the very top of our priorities must be an unswerving commitment and devotion to the state of Israel,’ while Pat Robertson said ‘The future of this Nation [America] may be at stake, because God will bless those that bless Israel.’ As for John Hagee, chairman of Christians United for Israel, he once declared: ‘The United States must join Israel in a pre-emptive military strike against Iran to fulfill God’s plan for both Israel and the West.’[12]

Gullible Christians not only see God’s hand whenever Israel advances in its self-prophesized destiny of world domination, but are ready to see Israeli leaders themselves as prophets when they announce their own false-flag crimes.[13]

________

[4] Read Gunnar Heinsohn, “The Restauration of Ancient History” (webpage), “The Revision of Ancient History – A Perspective” (webpage).

[5] Robert A. Markys, The Jesuit Order as a Synagogue of Jews: Jesuits of Jewish Ancestry and Purity-of-Blood Laws in the Early Society of Jesus, Brill, 2009.

[6] Lucien Wolf, Report on the “Marranos” or Crypto-Jews of Portugal, Anglo-Jewish Association, 1926.

[7] Vincent Schmid, “Calvin et les Juifs : Prémices du dialogue judéo-chrétien chez Jean Calvin,” 2008, on www.racinesetsources.ch.

[8] Cecil Roth, A History of the Jews in England (1941), Clarendon Press, 1964, p. 148.

[9] Isaac Disraeli, ‘Commentaries on the Life and Reign of Charles the First, King of England’, 2 vols., 1851, quoted in Archibald Maule Ramsay, The Nameless War, 1952 (archive.org).

[10] Hilaire Belloc, The Jews, Constable & Co., 1922 (archive.org), p. 223.

[11] Joseph Canfield, The Incredible Scofield and His Book, Ross House Books, 2004, pp. 219–220.

[12] Jill Duchess of Hamilton, God, Guns and Israel: Britain, The First World War And The Jews in the Holy City, The History Press, 2009 , kindle, e. 414-417.

[13] Michael Evans, The American Prophecies, Terrorism and Mid-East Conflict Reveal a Nation’s Destiny.

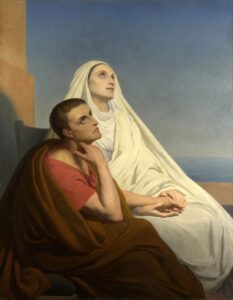

I am not finished with what I recently said about St Augustine. For the faithful, the crucial event in Augustine’s conversion happened when, at random, he picked up an epistle of Paul and read a verse that struck him like a bolt of lightning.

I am not finished with what I recently said about St Augustine. For the faithful, the crucial event in Augustine’s conversion happened when, at random, he picked up an epistle of Paul and read a verse that struck him like a bolt of lightning.