– For the context of these translations click here –

Louis the Pious and the death

of the king of Brittany.

Foreign policy

Louis the Pious waged war almost year after year, as befitted a Christian and believing ruler, mainly because of dynastic conflicts and internal political problems. But again and again, he also crossed the frontiers or had them crossed: as a universal ruler, he hardly ever took part in the campaigns himself but had others fight for him. This had long been the method of all rulers in the biggest massacres of the time. Pacts were scarcely of any interest any more.

In 815 a Saxon-Obotrite army attacked the Danes; but, after a series of devastations everywhere, it returned with forty hostages without having achieved anything. In 816 Louis sent his troops against the Sorbs. This time they ‘efficiently carried out’ (strenue compleverunt, Imperial Annals) the emperor’s orders and attacked them, as the sources say, ‘as swiftly as easily with the help of Christ’, and ‘with the help of God they gained the victory.’ The emperor, however, ‘gave himself up to hunting in the Vosges forest.’ At the other end of the empire, on the northern slopes of the Pyrenees, the Basques revolted and were ‘completely subdued’ (Annales regni Francorum).

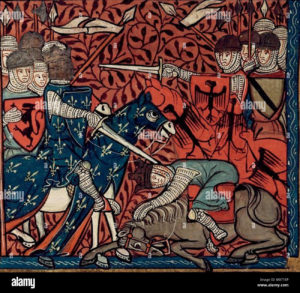

Louis repeatedly waged devastating campaigns against the Breton Levantines, whose princes claimed the title of king at various times. On several occasions, he attacked the ‘mendacious, proud and rebellious people’, whom even his father hadn’t managed to subdue completely and whom the Merovingians, before Charles and Pippin, had repeatedly tried to subdue. In the summer of 818, he marched in person—almost his only military campaign as emperor—with an army of Franks, Burgundians, Alamans, Saxons and Thuringians against the ‘Breton rebels, who in their audacity dared to name one of their own, named Morman, king, refusing all obedience’ (Anonymous).

The pious sovereign, of whom his contemporary Bishop Thegan carefully exalts that ‘he progressed from day to day in sacred virtues, the enumeration of which would lead too far’, crushed the Bretons with his arrogance. He reduced to ashes all the buildings except the churches, and amid all the fires and murders he had the monasticism of the country widely reported by the Abbot of Landévennec. To kill and to pray, to pray and to kill; so everything went well and everything was permitted, at least in the war, as long as it was in favour of the ‘orthodox’ side.

A great multitude was taken prisoner, plentiful cattle were taken from them, and the Bretons submitted ‘to the conditions imposed by the emperor, whatever they were… And such hostages were selected and taken as he ordered, and the whole territory was organised at his will’, writes Astronomus.

In 819 Louis sent an army across the Elbe against the Obotrites. Their deserting prince Sclaomir (809-819) was captured and taken to Aachen, his territory occupied and he was exiled. Shortly afterwards they defeated him again, but while still in Saxony he succumbed to an illness and in the meantime received the sacrament of baptism. The Slavic people on the banks of the Elbe were still totally pagan, and the supremacy of Louis was still exposed to serious uprisings in the years 838 and 839.

On the other side of his borders, the counts of the Spanish March penetrated across the Segre ‘as far as the interior of Spain’ and ‘from there happily returned with a great booty’, having ‘ravaged and burned everything’, as Astronomus writes. The imperial analyst also notes the devastation of fields, the burning of villages and ‘no small booty’, adding: ‘In the same way, after the autumn equinox the counts of the Breton Mark raided the possessions of a rebellious Breton named Wihomarc and devastated everything with blood and fire.’

In 824 the monarch marched again with three army groups—he personally commanded one—against the Bretons and their prince Wihomarc, Morman’s successor.

In forty days, according to Frankish sources, Louis the Pious ravaged ‘the whole country with blood and fire’, ‘punished it with a great devastation’ (magna plague). He was ‘the most pious of emperors’, as the chorepiscopus Thegan praises him, ‘for even before he respected his enemies, fulfilling the word of the evangelist who says ‘Forgive and you will be forgiven.’ Louis destroyed fields and forests, annihilated a good part of the flocks, killed many Bretons, took many prisoners and returned with hostages ‘of the disloyal people.’ King Wihomarc was soon afterwards surrounded in his own house by the people of Count Lambert of Nantes, who beat him to death.