capital residents

One more word about what I wrote the first day of the month.

Returning to the zone of my childhood and early adolescence, when I hadn’t yet been abused by my parents, doesn’t solve my future but makes me think…

First, it irritates me that people don’t write about their existential pains. If they did it would be much easier to save the Aryan man from the ongoing extinction, as I told Dale Jansen yesterday.

Transvaluing our values doesn’t mean accepting the legacy of the Enlightenment and thus being considered apostate. For example, the neo-normie Voltaire wrote in his Philosophical Dictionary that “it is natural that the children honour their parents”, a mandate taken directly from the Judeo-Christian decalogue (visitors who haven’t read the all too important Neo-Christianity PDF should read it now).

As Nietzsche knew, true apostasy lies in the transvaluation of all values. That includes replacing such a Judaeo-Christian command with the “Know thyself!” of Delphi. An insightful Aryan is already able to save his breed from extinction because he has identified the enemy: the Semitic malware with which the Aryan man has been infected for millennia. And when you know yourself the most natural thing is to keep a public blog, or personal diary, about your spiritual odyssey.

So back to autobiography. The zone where I lived happily many decades ago has horribly fallen due to the geometric reproduction of those whom I call Neanderthals. To boot, there are millions more cars in the capital and, worse, they have torn down many cosy houses to build soulless buildings.

A couple of days ago I went to a central intersection of avenues where I sat in a two-chair stall of a shoe boiler (my very dirty shoes had land that dated from my stay in Yautepec). The gentleman who was next to me, talking with the shoe polisher, commented that the palm trees (which I loved), that for decades were on the dividing strip of the avenues of the neighbourhood, were removed because the leftist government cut the budget and the palm trees weren’t irrigated… and died. So there are not only millions of Neanderthals, cars and soulless buildings in the streets of my most beloved memories, but the living beings that I loved died from negligence.

Yesterday I went to visit the friends of the park where I started playing chess fifty years ago. One of those old friends I met yesterday. I learned that another, much younger than us, rents a place in front of the coffee shop where we were that sells… meat! When he left I learned that this young man, who apparently has zero Indian blood (like the other friend), hasn’t procreated after four years of marriage. His wife recently went to Japan to vacation without his husband: something inconceivable for the values of my grandmas.

So I changed the naïve Indian people of Yautepec, where I lived for a few months, for the big city with this type of extremely decadent Westerner (yesterday, by the way, I had a passionate discussion with some of these chess players, including this young man, about these issues)! Even so, I don’t regret having left Yautepec because there it was impossible to go out for my daily walks due to the merciless sun (due to its great height above sea level, the capital is fairly tempered). The same young man who rents a carnivorous shop and allows his wife to travel alone told me the great truth about the neighbourhood where I now return: “the streets are very walkable”.

Why do the editors of the racialist webzines not saturate their articles with autobiographical vignettes such as these? To do so, accompanied by writing books about our most painful memories—that is, to comply with the religion of Delphi—would result in abandoning the monocausal POV of people like Nick Fuentes, who like me also has some Indian blood.

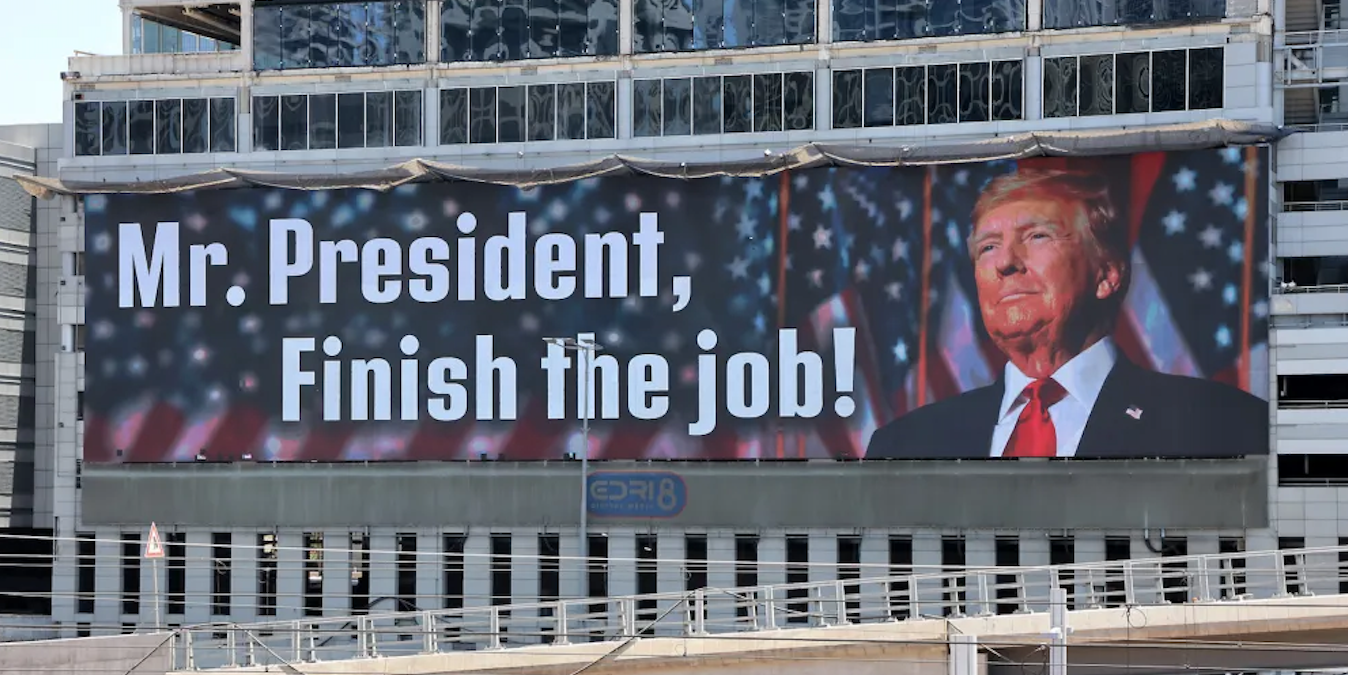

Why do the editors of the racialist webzines not saturate their articles with autobiographical vignettes such as these? To do so, accompanied by writing books about our most painful memories—that is, to comply with the religion of Delphi—would result in abandoning the monocausal POV of people like Nick Fuentes, who like me also has some Indian blood.