‘As Tom Holland says in Dominion, the triumph of Christianity in the West has been so complete that no one is left who truly stands outside it, which means that all revolutions against it are merely heresies, re-interpretations of Christian ideas’.

Category: Dominion (book)

Dominion, 40

The following quotes are taken from the final pages of ‘Woke’, the final chapter of Tom Holland’s Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World.

I have sought, in writing this book, to be as objective as possible. Yet this, when dealing with a theme such as Christianity, is not to be neutral. To claim, as I most certainly do, that I have sought to evaluate fairly both the achievements and the crimes of Christian civilisation is not to stand outside its moral frameworks, but rather—as Nietzsche would have been quick to point out—to stand within them.

Holland is a liberal, not a priest of the sacred words.

The people who, in his famous fable, continue to venerate the shadow of God are not just church-goers. All those in thrall to Christian morality—even those who may be proud to array themselves among God’s murderers—are included among their number. Inevitably, to attempt the tracing of Christianity’s impact on the world is to cover the rise and fall of empires, the actions of bishops and kings, the arguments of theologians, the course of revolutions, the planting of crosses around the world. It is, in particular, to focus on the doings of men. Yet that hardly tells the whole story. I have written much in this book about churches, and monasteries, and universities; but these were never where the mass of the Christian people were most influentially shaped. It was always in the home that children were likeliest to absorb the revolutionary teachings that, over the course of two thousand years, have come to be so taken for granted as almost to seem human nature. [pages 534-535]

I have omitted several paragraphs from these final pages in which Holland writes several autobiographical vignettes about how he was brought up by his godmother in the Anglican church. In those pages Holland correctly states that Christianity has been passed down from parents to their offspring for two millennia: it’s programming just as we program our computers. These autobiographical paragraphs are very important in that they explain how whites have been axiologically programmed for many generations, and anyone who wants to read them should simply buy Holland’s book. (I already knew that, although the difference between Holland and me is abysmal in that Christianity didn’t destroy his life.)

‘There is nothing particular about man. He is but a part of this world.’ Today, in the West, there are many who would agree with Himmler that, for humanity to claim a special status for itself, to imagine itself as somehow superior to the rest of creation, is an unwarrantable conceit. Homo sapiens is just another species. To insist otherwise is to cling to the shattered fragments of religious belief.

What Savitri Devi calls anthropocentrism.

Yet the implications of this view—which the Nazis, of course, claimed as their sanction for genocide—remain unsettling for many. Just as Nietzsche had foretold, freethinkers who mock the very idea of a god as a dead thing, a sky fairy, an imaginary friend, still piously hold to taboos and morals that derive from Christianity. In 2002, in Amsterdam, the World Humanist Congress affirmed ‘the worth, dignity and autonomy of the individual and the right of every human being to the greatest possible freedom compatible with the rights of others’. Yet this—despite humanists’ stated ambition to provide ‘an alternative to dogmatic religion’—was nothing if not itself a statement of belief. Himmler, at any rate, had understood what licence was opened up by the abandonment of Christianity.

The humanist assumption that atheism and liberalism go together was just that: an assumption. Without the biblical story that God had created humanity in his own image to draw upon, the reverence of humanists for their own species risked seeming mawkish and shallow. What basis—other than mere sentimentality—was there to argue for it? Perhaps, as the humanist manifesto declared, through ‘the application of the methods of science’. Yet this was barely any less of a myth than Genesis. As in the days of Darwin and Huxley, so in the twenty-first century, the ambition of agnostics to translate values ‘into facts that can be scientifically understood’ was a fantasy. It derived not from the viability of such a project, but from medieval theology. It was not truth that science offered moralists, but a mirror. Racists identified it with racist values; liberals with liberal values. The primary dogma of humanism—‘that morality is an intrinsic part of human nature based on understanding and a concern for others’—found no more corroboration in science than did the dogma of the Nazis that anyone not fit for life should be exterminated. The wellspring of humanist values lay not in reason, not in evidence-based thinking, but in history.

Now that instalment 40 concludes this series, I will include these quotes and my published comments about Dominion in a new PDF book that I may eventually title Paradigm Shift for Racialists. Incidentally, I’ll change the cover to another book we have published here, On Exterminationism, although I haven’t yet decided which image to use. It seems clear to me that if, like the Nazis, I have become an exterminationist and white nationalists don’t, it is because they still obey the Jews who wrote the New Testament, which is clear from what Holland went on to write in the final pages of his book:

When, in an astonishing breakthrough, collagen was extracted recently from the remains of one tyrannosaur fossil, its amino acid sequences turned out to bear an unmistakable resemblance to those of a chicken. The more the evidence is studied, the hazier the dividing line between birds and dinosaurs has become. The same, mutatis mutandis, might be said of the dividing line between agnostics and Christians. On 16 July 2018, one of the world’s best-known scientists, a man as celebrated for his polemics against religion as for his writings on evolutionary biology, sat listening to the bells of an English cathedral. ‘So much nicer than the aggressive-sounding “Allahu Akhbar”,’ Richard Dawkins tweeted. ‘Or is that just my cultural upbringing?’ The question was a perfectly appropriate one for an admirer of Darwin to ponder. It is no surprise, since humans, just like any other biological organism, are products of evolution, that its workings should be evident in their assumptions, beliefs and cultures. A preference for church bells over the sound of Muslims praising God does not just emerge by magic. Dawkins—agnostic, secularist and humanist that he is—absolutely has the instincts of someone brought up in a Christian civilisation.

Today, as the flood tide of Western power and influence ebbs, the illusions of European and American liberals risk being left stranded. Much that they have sought to cast as universal stands exposed as never having been anything of the kind. Agnosticism—as Huxley, the man who coined the word, readily acknowledged—ranks as ‘that conviction of the supremacy of private judgment (indeed, of the impossibility of escaping it) which is the foundation of the Protestant Reformation’. Secularism owes its existence to the medieval papacy. Humanism derives ultimately from claims made in the Bible: that humans are made in God’s image; that his Son died equally for everyone; that there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female. Repeatedly, like a great earthquake, Christianity has sent reverberations across the world. First there was the primal revolution: the revolution preached by Saint Paul. Then there came the aftershocks: the revolution in the eleventh century that set Latin Christendom upon its momentous course; the revolution commemorated as the Reformation; the revolution that killed God. All bore an identical stamp: the aspiration to enfold within its embrace every other possible way of seeing the world; the claim to a universalism that was culturally highly specific. That human beings have rights; that they are born equal; that they are owed sustenance, and shelter, and refuge from persecution: these were never self-evident truths.

The Nazis, certainly, knew as much—which is why, in today’s demonology, they retain their starring role. Communist dictators may have been no less murderous than fascist ones; but they—because communism was the expression of a concern for the oppressed masses—rarely seem as diabolical to people today. The measure of how Christian we as a society remain is that mass murder precipitated by racism tends to be seen as vastly more abhorrent than mass murder precipitated by an ambition to usher in a classless paradise.

This is absolutely fundamental to understanding the darkest hour of the white man.

Liberals may not believe in hell; but they still believe in evil. The fear of it puts them in its shade no less than it ever did Gregory the Great. Just as he lived in dread of Satan, so do we of Hitler’s ghost. Behind the readiness to use ‘fascist’ as an insult there lurks a numbing fear: of what might happen should it cease to be taken as an insult. If secular humanism derives not from reason or from science, but from the distinctive course of Christianity’s evolution—a course that, in the opinion of growing numbers in Europe and America, has left God dead—then how are its values anything more than the shadow of a corpse? What are the foundations of its morality, if not a myth?

A myth, though, is not a lie. At its most profound—as Tolkien, that devout Catholic, always argued—a myth can be true. To be a Christian is to believe that God became man and suffered a death as terrible as any mortal has ever suffered. This is why the cross, that ancient implement of torture, remains what it has always been: the fitting symbol of the Christian revolution. It is the audacity of it—the audacity of finding in a twisted and defeated corpse the glory of the creator of the universe—that serves to explain, more surely than anything else, the sheer strangeness of Christianity, and of the civilisation to which it gave birth. Today, the power of this strangeness remains as alive as it has ever been. It is manifest in the great surge of conversions that has swept Africa and Asia over the past century; in the conviction of millions upon millions that the breath of the Spirit, like a living fire, still blows upon the world; and, in Europe and North America, in the assumptions of many more millions who would never think to describe themselves as Christian. All are heirs to the same revolution: a revolution that has, at its molten heart, the image of a god dead on a cross…

Crucifixion was not merely a punishment. It was a means to achieving dominance: a dominance felt as a dread in the guts of the subdued. Terror of power was the index of power. That was how it had always been, and always would be. It was the way of the world. For two thousand years, though, Christians have disputed this. Many of them, over the course of this time, have themselves become agents of terror. They have put the weak in their shadow; they have brought suffering, and persecution, and slavery in their wake. Yet the standards by which they stand condemned for this are themselves Christian; nor, even if churches across the West continue to empty, does it seem likely that these standards will quickly change. ‘God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong.’ This is the myth that we in the West still persist in clinging to. [pages 537-542, bold type added]

Dominion! The paradigm shift proposed by The West’s Darkest Hour is simple: Christian morality is the primary cause of Aryan decline, not Jewish subversion. White nationalists will never solve the Jewish problem because, unlike Himmler, they are programmed by Judeo-Christian morality.

It is paradoxical, but as long as they believe that the JQ is the primary cause they will never settle accounts with Jewry. Settling accounts involves transvaluing all Christian values for pre-Christian values (it’s impossible to solve the Jewish problem using a framework of values that is itself utterly Judeo-Christian!). Transvaluation means repudiating all of Western history from Constantine onwards as well as having the spirit of Hitler, and the coming Kalki, as the avatars to follow as Savitri rightly said in her book we translated.

Dominion, 39

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

On 5 October 2017, allegations about what Harvey Weinstein had been getting up to in his fourth-floor suite at the Peninsula broke in the New York Times. An actress meeting him there for what she had thought was a business breakfast had found the producer wearing nothing but his bespoke bathrobe. Perhaps, he had suggested, she could give him a massage? Or how about watching him shower? Two assistants who had met with Weinstein in his suite reported similar encounters. Over the weeks and months that followed, further allegations were levelled against him: harassment, assault, rape. Among the more than eighty women going public with accusations was Uma Thurman, the actor who had played Mia Wallace in Pulp Fiction and become the movie’s pin-up. Meanwhile, where celebrity forged a path, many other women followed. A campaign that urged women to report incidents of harassment or assault under the hashtag #MeToo actively sought to give a voice to the most marginalised and vulnerable of all: janitors, fruit-pickers, hotel housekeepers. Already that year, the summons to a great moral awakening, a call for men everywhere to reflect on their sins, and repent them, had been much in the air. On 21 January, a million women had marched through Washington, DC. Other, similar demonstrations had been held around the world. The previous day, a new president, Donald J. Trump, had been inaugurated in the American capital. He was, to the organisers of the women’s marches, the very embodiment of toxic masculinity: a swaggering tycoon who had repeatedly been accused of sexual assault, who had bragged of grabbing ‘pussy’, and who, during the recently concluded presidential campaign, had paid hush money to a porn star. Rather than make the marches about Trump, however, the organisers had sought a loftier message: to sound a clarion call against injustice, and discrimination, and oppression wherever it might be found. ‘Yes, it’s about feminism. But it’s about more than that. It’s about basic equality for all people.’

The echo, of course, was of Martin Luther King. Repeatedly, in the protests against misogyny that swept America during the first year of Trump’s presidency, the name and example of the great Baptist preacher were invoked. Yet Christianity, which for King had been the fount of everything he ever campaigned for, appeared to many who marched in 2017 part of the problem. Evangelicals had voted in large numbers for Trump. Roiled by issues that seemed to them not just unbiblical, but directly antithetical to God’s purposes—abortion, gay marriage, transgender rights—they had held their noses and backed a man who, pussy-grabbing and porn stars notwithstanding, had unblushingly cast himself as the standard-bearer for Christian values. Unsurprisingly, then, hypocrisy had been added to bigotry on the charge sheet levelled against them by progressives. America, it seemed to many feminists, risked becoming a misogynist theocracy. Three months after the Women’s March, a television series made gripping drama out of this dread. The Handmaid’s Tale was set in a country returned to a particularly nightmarish vision of seventeenth century New England. Adapted from a dystopian novel by the Canadian writer Margaret Atwood, it provided female protestors against Trump with a striking new visual language of protest. White bonnets and red cloaks were the uniform worn by ‘handmaids’: women whose ability to reproduce had rendered them, in a world crippled by widespread infertility, the objects of legalised rape. Licence for the practice was provided by an episode in the Bible. The parody of evangelicals was as dark as it was savage. The Handmaid’s Tale—as all great dystopian fiction tends to be—was less prophecy than satire. The TV series cast Trump’s America as a society rent in two: between conservatives and liberals; between reactionaries and progressives; between dark-souled televangelists and noble-hearted foes of patriarchy.

Protestors summon men to exercise control

over their lusts–just as the Puritans had once done.

[This image & footnote appear in Holland’s book—Ed.]

Yet the divisions satirised by The Handmaid’s Tale were in truth very ancient. They derived ultimately, not from the specifics of American politics in the twenty-first century, but from the very womb of Christianity. Blessed be the fruit. There had always existed, in the hearts of the Christian people, a tension between the demands of tradition and the claims of progress, between the prerogatives of authority and the longing for reformation, between the letter and the spirit of the law. The twenty-first century marked, in that sense, no radical break with what had gone before. That the great battles in America’s culture war were being fought between Christians and those who had emancipated themselves from Christianity was a conceit that both sides had an interest in promoting. It was no less of a myth for that. In reality, Evangelicals and progressives were both recognisably bred of the same matrix. If opponents of abortion were the heirs of Macrina, who had toured the rubbish tips of Cappadocia looking for abandoned infants to rescue, then those who argued against them were likewise drawing on a deeply rooted Christian supposition: that every woman’s body was her own, and to be respected as such by every man. Supporters of gay marriage were quite as influenced by the Church’s enthusiasm for monogamous fidelity as those against it were by biblical condemnations of men who slept with men. To install transgender toilets might indeed seem an affront to the Lord God, who had created male and female; but to refuse kindness to the persecuted was to offend against the most fundamental teachings of Christ. In a country as saturated in Christian assumptions as the United States, there could be no escaping their influence—even for those who imagined that they had. America’s culture wars were less a war against Christianity than a civil war between Christian factions. [a war between Christianity and what, on this site, we call ‘neochristianity’—Ed.]

In 1963, when Martin Luther King addressed hundreds of thousands of civil rights protestors assembled in Washington, he had aimed his speech at the country beyond the capital as well—at an America that was still an unapologetically Christian nation. By 2017, things were different. Among the four co-chairs of the Women’s March was a Muslim. Marching through Washington were Sikhs, Buddhists, Jews. Huge numbers had no faith at all. Even the Christians among the organisers flinched from attempting to echo the prophetic voice of a Martin Luther King. Nevertheless, their manifesto was no less based in theological presumptions than that of the civil rights movement had been. Implicit in #MeToo was the same call to sexual continence that had reverberated throughout the Church’s history. Protestors who marched in the red cloaks of handmaids were summoning men to exercise control over their lusts just as the Puritans had done. Appetites that had been hailed by enthusiasts for sexual liberation as Dionysiac stood condemned once again as predatory and violent. The human body was not an object, not a commodity to be used by the rich and powerful as and when they pleased. Two thousand years of Christian sexual morality had resulted in men as well as women widely taking this for granted. Had it not, then #MeToo would have had no force.

The tracks of Christian theology, Nietzsche had complained, wound everywhere. In the early twenty-first century, they led—as they had done in earlier ages—in various and criss-crossing directions. They led towards TV stations on which televangelists preached the headship of men over women; and they led as well towards gender studies departments, in which Christianity was condemned for heteronormative marginalisation of LGBTQIA+. Nietzsche had foretold it all. God might be dead, but his shadow, immense and dreadful, continued to flicker even as his corpse lay cold. Feminist academics were no less in thrall to it, no less its acolytes, than were the most fire-breathing preachers. God could not be eluded simply by refusing to believe in his existence. Any condemnation of Christianity as patriarchal and repressive derived from a framework of values that was itself utterly Christian. [bold added—Ed.]

‘The measure of a man’s compassion for the lowly and the suffering comes to be the measure of the loftiness of his soul.’ It was this, the epochal lesson taught by Jesus’ death on the cross, that Nietzsche had always most despised about Christianity. Two thousand years on, and the discovery made by Christ’s earliest followers—that to be a victim might be a source of power—could bring out millions onto the streets. Wealth and rank, in Trump’s America, were not the only indices of status. So too were their opposites. Against the priapic thrust of towers fitted with gold-plated lifts, the organisers of the Women’s March sought to invoke the authority of those who lay at the bottom of the pile. The last were to be first, and the first were to be last. Yet how to measure who ranked as the last and the first? As they had ever done, all the multiple intersections of power, all the various dimensions of stratification in society, served to marginalise some more than others. Woman marching to demand equality with men always had to remember—if they were wealthy, if they were educated, if they were white—that there were many among them whose oppression was greater by far than their own: ‘Black women, indigenous women, poor women, immigrant women, disabled women, Muslim women, lesbian, queer and trans women.’ The disadvantaged too might boast their own hierarchy.

That it was the fate of rulers to be brought down from their thrones, and the humble to be lifted up, was a reflection that had always prompted anxious Christians to check their privilege. It had inspired Paulinus to give away his wealth, and Francis to strip himself naked before the Bishop of Assisi, and Elizabeth of Hungary to toil in a hospital as a scullery maid. Similarly, a dread of damnation, a yearning to be gathered into the ranks of the elect, a desperation to be cleansed of original sin, had provided, from the very moment the Pilgrim Fathers set sail, the surest and most fertile seedbed for the ideals of the American people. Repeatedly, over the course of their history, preachers had sought to awaken them to a sense of their guilt, and to offer them salvation. Now, in the twenty-first century, there were summons to a similar awakening. When, in October 2017, the leaders of the Women’s March organised a convention in Detroit, one panel in particular found itself having to turn away delegates. ‘Confronting White Womanhood’ offered white feminists the chance to acknowledge their own entitlement, to confess their sins and to be granted absolution. The opportunity was for the rich and the educated to have their eyes opened; to stare the reality of injustice in the face; truly to be awakened. Only through repentance was salvation to be obtained. The conveners, though, were not merely addressing the delegates in the conference hall. Their gaze, as the gaze of preachers in America had always been, was fixed on the world beyond. Their summons was to sinners everywhere. Their ambition was to serve as a city on a hill.

Christianity, it seemed, had no need of actual Christians for its assumptions still to flourish. Whether this was an illusion, or whether the power held by victims over their victimisers would survive the myth that had given it birth, only time would tell. As it was, the retreat of Christian belief did not seem to imply any necessary retreat of Christian values. Quite the contrary. Even in Europe—a continent with churches far emptier than those in the United States—the trace elements of Christianity continued to infuse people’s morals and presumptions so utterly that many failed even to detect their presence. Like dust particles so fine as to be invisible to the naked eye, they were breathed in equally by everyone: believers, atheists, and those who never paused so much as to think about religion. Had it been otherwise, then no one would ever have got woke. [pages 528-533, bold added—Ed.]

Dominion, 38

by Tom Holland

Europeans had been able to take for granted the impregnability of their own continent. Mass migration was something that they brought to the lands of non-Europeans—not the other way round.

Since the end of the Second World War, however, that had changed. Attracted by higher living standards, large numbers of immigrants from non-European countries had come to settle in Western Europe. For decades, the pace and scale of immigration into Germany had been carefully regulated; but now it seemed that control was at risk of breaking down. Merkel, explaining the facts to a sobbing teenager, knew full well the crisis that, even as she spoke, was building beyond Germany’s frontiers. All that summer, thousands upon thousands of migrants and refugees from Muslim countries had been moving through the Balkans. The spectacle stirred deeply atavistic fears. In Hungary, there was talk of a new Ottoman invasion. Even in Western Europe, in lands that had never been conquered by Muslim armies, there were many who felt a sense of unease. Dread that all the East might be on the move reached back a long way. ‘The plain was dark with their marching companies, and as far as eyes could strain in the mirk there sprouted, like a foul fungus growth, all about the beleaguered city great camps of tents, black or sombre red.’ So Tolkien, writing in 1946, had described the siege of Minas Tirith, bulwark of the free lands of the West, by the armies of Sauron. The climax of The Lord of the Rings palpably echoed the momentous events of 955: the attack on Augsburg and the battle of the Lech…

In 2003, a film of The Lord of the Rings had brought Aragorn’s victory over the snarling hordes of Mordor to millions who had never heard of the battle of the Lech. Burnished and repackaged for the twenty-first century, Otto’s defence of Christendom still possessed a spectral glamour.

Its legacy, though, that summer of 2014, was shaded by multiple ironies. Otto’s mantle was taken up not by the chancellor of Germany, but by the prime minister of Hungary. Victor Orbán had until recently been a self-avowed atheist; but this did not prevent him from doubting—much as Otto might have done—whether unbaptised migrants could ever truly be integrated. ‘This is an important question, because Europe and European culture have Christian roots.’ That September, ordering police to remove refugees from trains and put up fences along Hungary’s southern border, he warned that Europe’s soul was at stake. Merkel, as she tracked the migrant crisis, had come to an identical conclusion. Her response, however, was the opposite of Orbán’s. Although pressed by ministers in her own ruling coalition to close Germany’s borders, she refused. Huge crowds of Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis began crossing into Bavaria. Soon, upwards of ten thousand a day were pouring in. Crowds gathered at railway stations to cheer them; football fans raised banners at matches to proclaim them welcome. The scenes, the chancellor declared, ‘painted a picture of Germany which can make us proud of our country’.

Merkel, no less than Orbán, stood in the shadow of her people’s history. She knew where a dread of being swamped by aliens might lead. Earlier generations had been more innocent. Tolkien, when he drew on episodes from early medieval history for the plot of The Lord of the Rings, had never meant to equate the Hungarians or the Saracens with the monstrous evil embodied by Mordor. The age of migrations was sufficiently remote, he had assumed, that there was little prospect of his readers believing that. He had never had any intention of demonising entire peoples—ancient or modern. ‘I’m very anti that kind of thing’…

Himmler, a man whose loathing for Christianity had not prevented him from admiring the martial feats of Christian emperors, had hallowed Otto’s father as the supreme model of Germanic heroism. It was darkly rumoured that he claimed to be the Saxon king’s reincarnation. Hitler, although privately contemptuous of Himmler’s more mystical leanings, had himself been obsessed by the Holy Lance. A relic of the crucifixion had been transmogrified into an emblem of Nazism. Seventy years on from Hitler’s suicide, in a country still committed to doing penance for his crimes, there had never been any prospect of Angela Merkel riding to fight a new battle of the Lech. The truly, the only Christian thing to do, faced by the floodtide of misery lapping at Europe’s borders, was to abandon any lingering sense of the continent as Christendom and open it up to the wretched of the earth.

Always, from the very beginnings of the Church, there had been tension between Christ’s commandment to his followers that they should go into the world and preach the good news to all creation, and his parable of the Good Samaritan. Merkel was familiar with both. Her father had been a pastor, her mother no less devout. Her childhood home had been a hostel for people with disabilities—people much like Reem Sahwil. ‘The daily message was: Love your neighbour as yourself. Not just German people. God loves everybody.’ For two millennia, Christians had been doing their best to put these teachings into practice. Merkel, by providing refuge to the victims of war in the Middle East, was doing nothing that Gregory of Nyssa, sixteen centuries previously, had not similarly done. Offer charity, he had urged his congregants, for the spectacle of refugees living like animals was a reproach to every Christian. ‘Their roof is the sky. For shelter they use porticos, alleys, and the deserted corners of the town. They hide in the cracks of walls like owls.’ Yet Merkel, when she sought to justify the opening of her country’s borders—a volte-face all the more dramatic for seeming so out of character—pointedly refused to frame it as a gesture of Christian charity…

A morality existed that trumped all differences of culture—and differences of religion too. It was with this argument that Merkel sought to parry the objection of Orbán that a Muslim influx into Europe risked irrevocably transforming the Christian character of the continent. Islam, in its essentials, was little different from Christianity. Both might equally be framed within the bounds of a liberal, secular state. Islam, the chancellor insisted—slapping down any members of her own party who dared suggest otherwise—belonged in Germany…

Merkel, when she insisted that Islam belonged in Germany just as much as Christianity, was only appearing to be even-handed. To hail a religion for its compatibility with a secular society was decidedly not a neutral gesture. Secularism was no less bred of the sweep of Christian history than were Orbán’s barbed-wire fences.

Naturally, for it to function as its exponents wished it to function, this could never be admitted. The West, over the duration of its global hegemony, had become skilled in the art of repackaging Christian concepts for non-Christian audiences. A doctrine such as that of human rights was far likelier to be signed up to if its origins among the canon lawyers of medieval Europe could be kept concealed. The insistence of United Nations agencies on ‘the antiquity and broad acceptance of the conception of the rights of man’ was a necessary precondition for their claim to a global, rather than a merely Western, jurisdiction. Secularism, in an identical manner, depended on the care with which it covered its tracks. If it were to be embraced by Jews, or Muslims, or Hindus as a neutral holder of the ring between them and people of other faiths, then it could not afford to be seen as what it was: a concept that had little meaning outside of a Christian context. In Europe, the secular had for so long been secularised that it was easy to forget its ultimate origins. [pages 516-521]

Dominion, 37

by Tom Tolland

‘Why do they hate us?’

The president of the United States, in his address to a joint session of Congress, knew that he was speaking for Americans across the country when he asked this question. Nine days earlier, on 11 September, an Islamic group named al-Qaeda had launched a series of devastating attacks against targets in New York and Washington. Planes had been hijacked and then crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Thousands had died. George W. Bush, answering his own question, had no doubt as to the motives of the terrorists. They hated America’s freedoms. Her freedom of religion, her freedom of speech. Yet these were not exclusively American. Rather, they were universal rights. They were as much the patrimony of Muslims as of Christians, of Afghans as of Americans. This was why the hatred felt for Bush and his country across much of the Islamic world was based on misunderstanding. ‘Like most Americans, I just can’t believe it because I know how good we are.’ If American values were universal, shared by humans across the planet, regardless of creed or culture, then it stood to reason that Muslims shared them too. Bush, sitting in judgement on the terrorists who had attacked his country, condemned them not just for hijacking planes, but for hijacking Islam itself. ‘We respect the faith. We honor its traditions. Our enemy does not.’ It was in this spirit that the President, even as he ordered the American war machine to inflict a terrible vengeance on al-Qaeda, aimed to bring to the Muslim world freedoms that he believed in all devoutness to be no less Islamic than they were Western. First in Afghanistan, and then in Iraq, murderous tyrannies were overthrown. Arriving in Baghdad in April 2003, US forces pulled down statues of the deposed dictator. As they waited to be given sweets and flowers by a grateful people, they waited as well to deliver to Iraq the dues of freedom that Bush, a year earlier, had described as applying fully to the entire Islamic world. ‘When it comes to the common rights and needs of men and women, there is no clash of civilizations.’

Except that sweets and flowers were notable by their absence on the streets of Iraq. Instead, the Americans were greeted with mortar attacks, and car bombs, and improvised explosive devices. The country began to dissolve into anarchy. In Europe, where opposition to the invasion of Iraq had been loud and vocal, the insurgency was viewed with often ill-disguised satisfaction. Even before 9/11, there were many who had felt that ‘the United States had it coming’. By 2003, with US troops occupying two Muslim countries, the accusation that Afghanistan and Iraq were the victims of naked imperialism was becoming ever more insistent. What was all the President’s fine talk of freedom if not a smokescreen? As to what it might be hiding, the possibilities were multiple: oil, geopolitics, the interests of Israel. Yet Bush, although a hard-boiled businessman, was not just about the bottom line. He had never thought to hide his truest inspiration. Asked while still a candidate for the presidency to name his favourite thinker, he had answered unhesitatingly: ‘Christ, because he changed my heart.’ Here, unmistakably, was an Evangelical. Bush, in his assumption that the concept of human rights was a universal one, was perfectly sincere. Just as the Evangelicals who fought to abolish the slave trade had done, he took for granted that his own values—confirmed to him in his heart by the Spirit— were values fit for all the world. He no more intended to bring Iraq to Christianity than British Foreign Secretaries, back in the heyday of the Royal Navy’s campaign against slavery, had aimed to convert the Ottoman Empire. His ambition instead was to awaken Muslims to the values within their own religion that would enable them to see everything they had in common with America. ‘Islam, as practised by the vast majority of people, is a peaceful religion, a religion that respects others.’ Bush, asked to describe his own faith, might well have couched it in similar terms. What bigger compliment, then, could he possibly have paid to Muslims?

But Iraqis did not have their hearts opened to the similarity of Islam to American values. Their country continued to burn. To Bush’s critics, his talk of a war against evil appeared grotesquely misapplied. If anyone had done evil, then it was surely the leader of the world’s greatest military power, a man who had used all the stupefying resources at his command to visit death and mayhem on the powerless. In 2004 alone, US forces in Iraq variously bombed a wedding party, flattened an entire city, and were photographed torturing prisoners. [pages 505-507]

A Qur’an manuscript resting on a rehal.

Three pages further on, Holland continues:

Most menacing of all was the United Nations. Established in the aftermath of the Second World War, its delegates had proclaimed a Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To be a Muslim, though, was to know that humans did not have rights. There was no natural law in Islam. There were only laws authored by God. Muslim countries, by joining the United Nations, had signed up to a host of commitments that derived, not from the Qur’an or the Sunna, but from law codes devised in Christian countries: that there should be equality between men and women; equality between Muslims and non-Muslims; a ban on slavery; a ban on offensive warfare. Such doctrines, al-aqdisi sternly ruled, had no place in Islam. To accept them was to become an apostate. Al-Zarqawi, released from prison in 1999, did not forget al-Maqdisi’s warnings. In 2003, launching his campaign in Iraq, he went for a soft and telling target. On 19 August, a car bomb blew up the United Nations headquarters in the country. The UN’s special representative was crushed to death in his office. Twenty-two others were also killed. Over a hundred were left maimed and wounded. Shortly afterwards, the United Nations withdrew from Iraq.

‘Ours is a war not against a religion, not against the Muslim faith.’ President Bush’s reassurance, offered before the invasion of Iraq, was not one that al-Zarqawi was remotely prepared to accept. What most people in the West meant by Islam and what scholars like al-Maqdisi meant by it were not at all the same thing. What to Bush appeared the markers of its compatibility with Western values appeared to al-Maqdisi a fast-metastasising cancer…

To al-Maqdisi, the spectacle of Muslim governments legislating to uphold equality between men and women, or between Islam and other religions, was a monstrous blasphemy. The whole future of the world was at stake. God’s final revelation, the last chance that humanity had of redeeming itself from damnation, was directly threatened… His [al-Maqdisi’s] incineration by a US jet strike in 2006 did not serve to kill the hydra…

All that counted was the example of the Salaf. When al-Zarqawi’s disciples smashed the statues of pagan gods, they were following the example of Muhammad; when they proclaimed themselves the shock troops of a would-be global empire, they were following the example of the warriors who had humbled Heraclius; when they beheaded enemy combatants, and reintroduced the jizya, and took the women of defeated opponents as slaves, they were doing nothing that the first Muslims had not gloried in. The only road to an uncontaminated future was the road that led back to an unspoilt past. Nothing of the Evangelicals, who had erupted into the Muslim world with their gunboats and their talk of crimes against humanity, was to remain. [pages 510-512]

Dominion, 36

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

Seven months before Live Aid, its organisers had recruited many of the biggest acts in Britain and Ireland to a super-group: Band Aid. ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’, a one-off charity record, succeeded in raising so much money for famine relief that it would end up the best-selling single in the history of the UK charts. For all the peroxide, all the cross-dressing, all the bags of cocaine smuggled into the recording studio, the project was one born of the Christian past.

Reporting on the sheer scale of the suffering in Ethiopia, a BBC correspondent had described the scenes he was witnessing as ‘biblical’; stirred into action, the organisers of Band Aid had embarked on a course of action that reached for its ultimate inspiration to the examples of Paul and Basil. That charity should be offered to the needy, and that a stranger in a foreign land was no less a brother or sister than was a next-door neighbour, were principles that had always been fundamental to the Christian message.

Concern for the victims of distant disasters—famines, earthquakes, floods—was disproportionately strong in what had once been Christendom. The overwhelming concentration of international aid agencies there was no coincidence. Band Aid were hardly the first to ask whether Africans knew that it was Christmastime. In the nineteenth century, the same anxiety had weighed heavily on Evangelicals. Missionaries had duly hacked their way through uncharted jungles, campaigned against the slave trade, and laboured with all their might to bring the Dark Continent into the light of Christ. ‘A diffusive philanthropy is Christianity itself. It requires perpetual propagation to attest its genuineness.’ Such was the mission statement of the era’s most famous explorer, David Livingstone. Band Aid—in their ambition to do good, if not in their use of hair dye—were recognisably his heirs.

This was not, though, how their single was marketed. Anything that smacked of white people telling Africans what to do had become, by the 1980s, an embarrassment. Admiration even for a missionary such as Livingstone, whose crusade against the Arab slave trade had been unstintingly heroic, had come to pall. His efforts to map the continent—far from serving the interests of Africans, as he had trusted they would—had instead only opened up its interior to conquest and exploitation.

A decade after his death from malaria in 1873, British adventurers had begun to expand deep into the heart of Africa. Other European powers had embarked on a similar scramble. France had annexed much of north Africa, Belgium the Congo, Germany Namibia. By the outbreak of the First World War, almost the entire continent was under foreign rule. Only the Ethiopians had succeeded in maintaining their independence. Missionaries, struggling to continue with their great labour of conversion, had found themselves stymied by the brute nature of European power. How were Africans to believe talk of a god who cared for the oppressed and the poor when the whites, the very people who worshipped him, had seized their lands and plundered them for diamonds, and ivory, and rubber? A colonial hierarchy in which blacks were deemed inferior had seemed a peculiar and bitter mockery of the missionaries’ insistence that Christ had died for all of humanity.

By the 1950s, when the tide of imperialism in Africa had begun to ebb as fast it had originally flowed, it might have seemed that Christianity was doomed to retreat as well, with churches crumbling before the hunger of termites, and Bibles melting into mildewed pulp. But that—in the event—was not what had happened at all! [pages 497-499]

A few pages further on Tom Holland discusses the case of South Africa:

The ending of apartheid and the election in 1994 of Mandela as South Africa’s first black president was one of the great dramas of Christian history: a drama woven through with deliberate echoes of the Gospels… The same faith that had inspired Afrikaners to imagine themselves a chosen people was also, in the long run, what had doomed their supremacy.

The pattern was a familiar one. Repeatedly, whether crashing along the canals of Tenochtitlan, or settling the estuaries of Massachusetts, or trekking deep into the Transvaal, the confidence that had enabled Europeans to believe themselves superior to those they were displacing was derived from Christianity. Repeatedly, though, in the struggle to hold this arrogance to account, it was Christianity that had provided the colonised and the enslaved with their surest voice. The paradox was profound.

No other conquerors, carving out empires for themselves, had done so as the servants of a man tortured to death on the orders of a colonial official. No other conquerors, dismissing with contempt the gods of other peoples, had installed in their place an emblem of power so deeply ambivalent as to render problematic the very notion of power. No other conquerors, exporting an understanding of the divine peculiar to themselves, had so successfully persuaded peoples around the globe that it possessed a universal import. [pages 503-504]

London bus in 1989 carrying the

‘Boycott Apartheid’ message.

The collapse of apartheid had been merely the aftershock of a far more convulsive earthquake. In 1989, even as de Klerk was resolving to set Mandela free, the Soviet empire had imploded. Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary: all had cast off the chains of foreign rule. East Germany, a rump hived off by the Soviets in the wake of the Second World War, had been absorbed into a reunified—and thoroughly capitalist—Germany. The Soviet Union itself had ceased to exist. Communism, weighed in the scales of history, had been found wanting… That the paradise on earth foretold by Marx had turned out instead to be closer to a hell only emphasised the degree to which the true fulfilment of progress was to be found elsewhere.

With the rout of communism, it appeared to many in the victorious West that it was their own political and social order that constituted the ultimate, the unimprovable form of government. Secularism; liberal democracy; the concept of human rights: these were fit for the whole world to embrace. The inheritance of the Enlightenment was for everyone: a possession for all of mankind. It was promoted by the West, not because it was Western, but because it was universal. The entire world could enjoy its fruits. It was no more Christian than it was Hindu, or Confucian, or Muslim. There was neither Asian nor European. Humanity was embarked as one upon a common road.

The end of history had arrived. [pages 504-505]

Dominion, 35

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

The opening pages of the next chapter, ‘Love: 1967, Abbey Road’ are so important in showing how the virus of Christian morality continued to mutate into neochristian morality, that I will quote them almost in full:

Sunday, 25 June. In St John’s Wood, one of London’s most affluent neighbourhoods, churchgoers were heading to evensong. Not the world’s most famous band, though. The Beatles were booked to play their largest-ever gig. For the first time, a programme featuring live sequences from different countries was to be broadcast simultaneously around the world—and the British Broadcasting Corporation, for its segment, had put up John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. The studios on Abbey Road were where, for the past five years, the Beatles had been recording the songs that had transformed popular music, and made them the most idolised young men on the planet. Now, before an audience of 350 million, they were recording their latest single. The song, with a chorus that anyone could sing, was joyously, catchily anthemic. Its message, written on cardboard placards in an assortment of languages, was intended to be readily accessible to a global village. Flowers, streamers and balloons all added to the sense of a party. John Lennon, alternately singing and chewing heavily on a wad of gum, offered the watching world a prescription with which neither Aquinas, nor Augustine, nor Saint Paul would have disagreed: ‘all you need is love’.

God, after all, was love. This was what it said in the Bible. For two thousand years, men and women had been pondering this revelation. Love, and do as you will. Many were the Christians who, over the course of the centuries, had sought to put this precept of Augustine’s into practice. For then, as a Hussite preacher had put it, ‘Paradise will open to us, benevolence will be multiplied, and perfect love will abound.’ But what if there were wolves? What then were the lambs to do? The Beatles themselves had grown up in a world scarred by war. Great stretches of Liverpool, their native city, had been levelled by German bombs. Their apprenticeship as a band had been in Hamburg, served in clubs manned by limbless ex-Nazis. Now, even as they sang their message of peace, the world again lay in the shadow of conflict.

Only three weeks before the broadcast from Abbey Road, war had broken out in the Holy Land. The blackened carcasses of Egyptian and Syrian planes littered landscapes once trodden by biblical patriarchs. Israel, the Jewish homeland promised by the British in 1917, and which had finally been founded in 1948, had won in only six days a stunning victory over neighbours pledged to its annihilation. Jerusalem, the city of David, was—for the first time since the age of the Caesars—under Jewish rule. Yet this offered no resolution to the despair and misery of those displaced from what had previously been Palestine. Just the opposite. Across the world, like napalm in a Vietnamese jungle, hatreds seemed to be burning out of control. Most terrifying of all were the tensions between the world’s two superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States. Victory over Hitler had brought Russian troops into the heart of Europe. Communist governments had been installed in ancient Christian capitals: Warsaw, Budapest, Prague. An iron curtain now ran across the continent. Armed as both sides were with nuclear missiles, weapons so lethal that they had the potential to wipe out all of life on earth, the stakes were grown apocalyptic. Humanity had arrogated to itself what had always previously been viewed as a divine prerogative: the power to end the world.

How, then, could love possibly be enough? The Beatles—although roundly mocked for their message—were not alone in believing that it might be. A decade earlier, in the depths of the American South, a Baptist pastor named Martin Luther King had pondered what Christ had meant by urging his followers to love their enemies. ‘Far from being the pious injunction of a utopian dreamer, this command is an absolute necessity for the survival of our civilisation. Yes, it is love that will save our world and our civilization, love even for enemies.’ King had not claimed, as the Beatles would in ‘All You Need Is Love’, that it was easy. He spoke as a black man, to a black congregation, living in a society blighted by institutionalised oppression. The civil war, although it had ended slavery, had not ended racism and segregation…

In the spring of 1963, writing from jail, he had reflected on how Saint Paul had carried the gospel of freedom to where it was most needed, heedless of the risks. Summoning the white clergy to break their silence and to speak out against the injustices suffered by blacks, King had invoked the authority of Aquinas and of his own namesake, Martin Luther. Above all, though— answering the charge of extremism—he had appealed to the example of his Saviour. Laws that sanctioned the hatred and persecution of one race by another, he declared, were laws that Christ himself would have broken. ‘Was not Jesus an extremist for love?’

The campaign for civil rights gave to Christianity an overt centrality in American politics that it had not had since the decades before the Civil War. King, by stirring the slumbering conscience of white Christians, succeeded in setting his country on a transformative new path. To talk of love as Paul had talked of it, as a thing greater than prophecy, or knowledge, or faith, had once again become a revolutionary act. King’s dream, that the glory of the Lord would be revealed, and all flesh see it together, helped to animate a great yearning across America—in West Coast coffee shops as in Alabama churches, on verdant campuses as on picket lines, among attorneys as among refuse-workers—for justice to roll on like a river, and righteousness like a never-failing stream. This was the same vision of progress that, in the eighteenth century, had inspired Quakers and Evangelicals to campaign for the abolition of slavery; but now, in the 1960s, the spark that had set it to flame with a renewed brilliance was the faith of African Americans…

That the Beatles agreed with King on the importance of love and had refused as a matter of principle to play for segregated audiences, did not mean that they were—as James Brown might have put it—‘holy’. Even though Lennon had first met McCartney at a church fête, all four had long since abandoned their childhood Christianity. It was, in the words of McCartney, a ‘goody-goody thing’: fine, perhaps, for a lonely woman wearing a face that she kept in a jar by the door, but not for a band that had conquered the world. Churches were stuffy, oldfashioned, boring—everything that the Beatles were not. In England, even the odd bishop had begun to suggest that the traditional Christian understanding of God was outmoded, and that the only rule was love.

In 1966, when Lennon claimed in a newspaper interview that the Beatles were ‘more popular than Jesus’, eyebrows were barely raised in his home country. Only four months later, after his comment had been reprinted in an American magazine, did the backlash hit. Pastors across the United States had long been suspicious of the Beatles. This was especially so in the South—the Bible Belt. Preachers there—unwittingly backing Lennon’s point—fretted that Beatlemania had become a form of idolatry; some even worried that it was all a communist plot. To many white evangelicals—shamed by the summons to repentance issued them by King, baffled by the sense of a moral fervour that had originated outside their own churches, and horrified by the spectacle of their daughters screaming and wetting themselves at the sight of four peculiar-looking Englishmen—the chance to trash Beatles records came as a blessed relief. Simultaneously, to racists unpersuaded by the justice of the civil rights movement, it provided an opportunity to rally the troops. The Ku Klux Klan leapt at the chance to cast themselves as the defender of Protestant values. Not content with burning records, they set to burning Beatles wigs. The band’s distinctive hairstyle—a shaggy moptop—seemed to clean-cut Klansmen a blasphemy in itself. ‘It’s hard for me to tell through the mopheads,’ one of them snarled, ‘whether they’re even white or black.’

None of which did much to alter Lennon’s views on Christianity. The Beatles did not—as Martin Luther King had done—derive their understanding of love as the force that animated the universe from a close reading of scripture. Instead, they took it for granted. Cut loose from its theological moorings, the distinctively Christian understanding of love that had done so much to animate the civil rights movement began to float free over an ever more psychedelic landscape. The Beatles were not alone, that summer of 1967, in ‘turning funny’. Beads and bongs were everywhere. Evangelicals were appalled. To them, the emergence of long-haired freaks with flowers in their hair seemed sure confirmation of the satanic turn that the world was taking. Blissed-out talk of peace and love was pernicious sloganeering: just a cover for drugs and sex…

Then, the following April, Martin Luther King was shot dead. An entire era seemed to have been gunned down with him: one in which liberals and conservatives, black progressives and white evangelicals, had felt able— however inadequately—to feel joined by a shared sense of purpose. As news of King’s assassination flashed across America, cities began to burn: Chicago, Washington, Baltimore. Black militants, impatient even before King’s murder with his pacifism and talk of love, pushed for violent confrontation with the white establishment. Many openly derided Christianity as a slave religion. Other activists, following where King’s campaign against racism had led, demanded the righting of what they saw as no less grievous sins. If it were wrong for blacks to be discriminated against, then why not women, or homosexuals? [pages 488-493]

My bold type.

Increasingly, to Americans disoriented by the moral whirligig of the age, Evangelicals promised solid ground. A place of refuge, though, might just as well be a place under siege. To many Evangelicals, feminism and the gay rights movement were an assault on Christianity itself. Equally, to many feminists and gay activists, Christianity appeared synonymous with everything that they were struggling against: injustice, and bigotry, and persecution. God, they were told, hates fags.

But did he? Conservatives, when they charged their opponents with breaking biblical commandments, had the heft of two thousand years of Christian tradition behind them; but so too, when they pressed for gender equality or gay rights, did liberals. Their immediate model and inspiration was, after all, a Baptist preacher. ‘There is no graded scale of essential worth,’ King had written a year before his assassination. ‘Every human being has etched in his personality the indelible stamp of the Creator. Every man must be respected because God loves him.’

Every woman too, a feminist might have added. Yet King’s words, while certainly bearing witness to an instinctive strain of patriarchy within Christianity, bore witness as well to why, across the Western world, this was coming to seem a problem. That every human being possessed an equal dignity was not remotely self-evident a truth. A Roman would have laughed at it. To campaign against discrimination on the grounds of gender or sexuality, however, was to depend on large numbers of people sharing in a common assumption: that everyone possessed an inherent worth.

The origins of this principle—as Nietzsche had so contemptuously pointed out—lay not in the French Revolution, nor in the Declaration of Independence, nor in the Enlightenment, but in the Bible. Ambivalences that came to roil Western society in the 1970s had always been perfectly manifest in the letters of Paul. Writing to the Corinthians, the apostle had pronounced that man was the head of woman; writing to the Galatians, he had exulted that there was no man or woman in Christ. Balancing his stern condemnation of same-sex relationships had been his rapturous praise of love. Raised a Pharisee, learned in the Law of Moses, he had come to proclaim the primacy of conscience. The knowledge of what constituted a just society was written not with ink but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on human hearts. Love, and do as you will. It was—as the entire course of Christian history so vividly demonstrated—a formula for revolution.

‘The wind blows wherever it pleases.’ That the times they were a-changin’ was a message Christ himself had taught. Again and again, Christians had found themselves touched by God’s spirit; again and again, they had found themselves brought by it into the light. Now, though, the Spirit had taken on a new form. No longer Christian, it had become a vibe. Not to get down with it was to be stranded on the wrong side of history. The concept of progress, unyoked from the theology that had given it birth, had begun to leave Christianity trailing in its wake. [pages 494-495]

My bold.

The choice that faced churches—an agonisingly difficult one—was whether to sit in the dust, shaking their fists at it in impotent rage, or whether to run and scramble in a desperate attempt to catch up with it. Should women be allowed to become priests? Should homosexuality be condemned as sodomy or praised as love? Should the age-old Christian project of trammelling sexual appetites be maintained or eased? None of these questions were easily answered. To those who took them seriously, they ensured endless and pained debate. To those who did not, they provided yet further evidence—if evidence were needed—that Christianity was on its way out. John Lennon had been right. ‘It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue about that; I know I’m right and I will be proved right.’

Yet atheists faced challenges of their own. Christians were not alone in struggling to square the rival demands of tradition and progress. Lennon, after walking out on his song-writing partnership with McCartney, celebrated his liberation with a song that listed Jesus alongside the Beatles as idols in which he no longer believed. Then, in October 1971, he released a new single: ‘Imagine’. The song offered Lennon’s prescription for global peace.

Imagine there’s no heaven, he sang, no hell below us. Yet the lyrics were religious through and through. Dreaming of a better world, a brotherhood of man, was a venerable tradition in Lennon’s neck of the woods. St George’s Hill, his home throughout the heyday of the Beatles, was where the Diggers had laboured three hundred years previously. Rather than emulate Winstanley, however, Lennon had holed up inside a gated community, complete with a Rolls-Royce and swimming pool. ‘One wonders what they do with all their dough.’ So a pastor had mused back in 1966. The video of ‘Imagine’, in which Lennon was seen gliding around his recently purchased seventy-two-acre Berkshire estate, provided the answer. In its hypocrisy no less than in its dreams of a universal peace, Lennon’s atheism was recognisably bred of Christian marrow. A good preacher, however, was always able to take his flock with him. The spectacle of Lennon imagining a world without possessions while sitting in a huge mansion did nothing to put off his admirers. As Nietzsche spun furiously in his grave, ‘Imagine’ became the anthem of atheism. A decade later, when Lennon was shot dead by a crazed fan, he was mourned not just as one half of the greatest song-writing partnership of the twentieth century, but as a martyr. [pages 495-496]

The fact that the youth didn’t revolt when I was much younger at the sight of Lennon disowning the English roses of his country to marry a fucking non-white, means that they have embraced the cause of their ethno-suicide.

Not everyone was convinced. ‘Now, since his death, he’s become Martin Luther Lennon.’ Paul McCartney had known Lennon too well ever to mistake him for a saint. His joke, though, was also a tribute to King: a man who had flown into the light of the dark black night. ‘Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, “What are you doing for others?”’ McCartney, for all his dismissal of ‘goody goody stuff’, was not oblivious to the tug of an appeal like this.

In 1985, asked to help relieve a devastating famine in Ethiopia by taking part in the world’s largest-ever concert, he readily agreed. Live Aid, staged simultaneously in London and Philadelphia, the city of brotherly love, was broadcast to billions. Musicians who had spent their careers variously bedding groupies and snorting coke off trays balanced on the heads of dwarves played sets in aid of the starving. As night fell over London, and the concert in Wembley stadium reached its climax, lights picked out McCartney at a piano. The number he sang, ‘Let It Be’, had been the last single to be released by the Beatles while they were still together. ‘When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me.’ Who was Mary? Perhaps, as McCartney himself claimed, his mother; but perhaps, as Lennon had darkly suspected, and many Catholics had come to believe, the Virgin. Whatever the truth, no one that night could hear him. His microphone had cut out.

It was a performance perfectly appropriate to the paradoxes of the age. [pages 496-497]

Think of the stunning woman in my previous post. Couldn’t Lennon, with all his fame and money, have married someone like her? In my humble opinion, all whites—racialists included!—who listen not only to the Beatles but to rock in general, or its contemporary derivatives, are betraying their race. Incidentally, I’m glad Mark David Chapman killed this guy. The most subversive thing an American ruler could do in the future is to pardon him, get him out of prison.

Dominion, 34

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

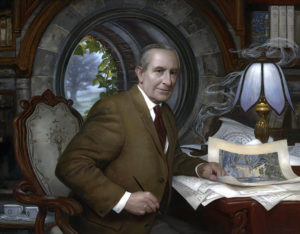

The section ‘In the Darkness Bind Them’ of Tom Holland’s chapter ‘Shadow’ opens with a few pages describing the life and work of J.R.R. Tolkien; and mentions the fascinating anecdote that, in the muddy trenches of the Somme in the First World War, soldiers Tolkien and Hitler were on opposite sides. Otto Dix, mentioned in my entry of the day before yesterday, was also on the side fighting against Tolkien. After those pages, Holland writes:

In 1938, a German editor wishing to publish him had written to ask if he were of Jewish origin. ‘I regret,’ Tolkien had replied, ‘that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.’ That the Nazis’ racism lacked any scientific basis he took for granted; but his truest objection to it was as a Christian. Of course, steeped in the literature of the Middle Ages as he was, he knew full well the role played by his own Church in the stereotyping and persecution of the Jews. In his imaginings, however, he saw them not as the hook-nosed vampires of medieval calumny, but rather as ‘a holy race of valiant men, the people of Israel the lawful children of God’.

These lines, from an Anglo-Saxon poem on the crossing of the Red Sea, were precious to Tolkien, for he had translated them himself. There was in them the same sense of identification with Exodus as had inspired Bede. Moses, in the poem, was represented as a mighty king, ‘a prince of men with a marching company’. Tolkien, writing The Lord of the Rings even as the Nazis were expanding their empire from the Atlantic to Russia, draw freely on such poetry for his own epic. Central to the plot was the return of a king: an heir to a long-abandoned throne named Aragorn. If the armies of Mordor were satanic like those of Pharaoh, then Aragorn—emerging from exile to deliver his people from slavery—had more than a touch of Moses. As in Bede’s monastery, so in Tolkien’s study: a hero might be imagined as simultaneously Christian and Jewish.

This was no isolated, donnish eccentricity. Across Europe, the readiness of Christians to identify themselves with the Jews had become the measure of their response to the greatest catastrophe in Jewish history. Tolkien—ever the devout Catholic—was doing nothing that popes had not also done. In September 1938, the ailing Pius XI had declared himself spiritually a Jew. One year later, with Poland defeated and subjected by German forces to an unspeakably brutal occupation, his successor had issued his first public letter to the faithful.

Pius XII, lamenting the ploughing of blood-drenched furrows with swords, pointedly cited Paul: ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek.’ Always, from the earliest days of the Church, this was a phrase that had particularly served to distinguish Christianismos from Ioudaismos: Christianity from Judaism. Between Christians, who celebrated the Church as the mother of all nations, and Jews, appalled at any prospect of having their distinctiveness melt away into the great mass of humanity, the dividing line had long been stark. But that was not how it seemed to the Nazis. When Pius XII quoted Genesis to rebuke those who would forget that humanity had a common origin, and that all the peoples of the world had a duty of charity to one another, the response from Nazi theorists was vituperative. To them, it appeared self-evident that universal morality was a fraud perpetrated by Jews. [pages 480-481]

But it isn’t self-evident to racialist anti-Semites that the New Testament is toxic to white people.

‘Can we still tolerate our children being obliged to learn that Jews and Negroes, just like Germans or Romans, are descended from Adam and Eve, simply because a Jewish myth says so?’ Not merely pernicious, the doctrine that all were one in Christ ranked as an outrage against the fundamentals of science. For centuries, the Nordic race had been infected by it. The consequence was a mutilation of what should properly have been left whole: a circumcision of the mind. ‘It is the Jew Paul who must be considered as the father of all this, as he, in a very significant way, established the principles of the destruction of a worldview based on blood.’

Christians, confronted by a regime committed to the repudiation of the most fundamental tenets of their faith—the oneness of the human race, the obligation of care for the weak and the suffering—had a choice to make. Did the Church, as a pastor named Dietrich Bonhoeffer had put it as early as 1933, have ‘an unconditional obligation towards the victims of any social order, even where those victims do not belong to the Christian community’—or did it not? Bonhoeffer’s own answer to that question would see him conspire against Hitler’s life, and end up being hanged in a concentration camp.

There were many other Christians too who passed the test. Some spoke out publicly. Others, more clandestinely, did what they could to shelter their Jewish neighbours, in cellars and attics, in the full awareness that to do so was to risk their own lives. Church leaders, torn between speaking with the voice of prophecy against crimes almost beyond their comprehension and a dread that to do so might risk the very future of Christianity, walked an impossible tightrope. ‘They deplore the fact that the Pope does not speak,’ Pius had lamented privately in December 1942. ‘But the pope cannot speak. If he spoke, things would be worse.’

Perhaps, as his critics would later charge, he should have spoken anyway. But Pius understood the limits of his power. By pushing things too far he might risk such measures as he was able to take. Jews themselves understood this well enough. In the pope’s summer residence, five hundred were given shelter. In Hungary, priests frantically issued baptismal certificates, knowing that they might be shot for doing so. In Romania, papal diplomats pressed the government not to deport their country’s Jews—and the trains were duly halted by ‘bad weather’. Among the SS, the pope was derided as a rabbi. [pages 481-482]

Keep in mind that this happened before the Second Vatican Council. Catholic white nationalists are either ignorant or dishonest in facing the fact that the Christian mind was already infected before such a Council. A couple of pages later Holland adds:

Otto Dix, far from admiring the Nazis for turning the world on its head, was revolted by them. They in turn dismissed him as a degenerate. Sacked from his teaching post in Dresden, forbidden to exhibit his paintings, he had turned to the Bible as his surest source of inspiration. In 1939, he had painted the destruction of Sodom. Fire was shown consuming a city that was unmistakably Dresden. The image had proven prophetic.

As the tide of war turned against Germany, so British and American planes had begun to visit ruin on the country’s cities. In July 1943, in an operation code-named Gomorrah, a great sea of fire had engulfed much of Hamburg. Back in Britain, a bishop named George Bell—a close friend of Bonhoeffer’s—spoke out in public protest. ‘If it is permissible to drive inhabitants to desire peace by making them suffer, why not admit pillage, burning, torture, murder, violation?’ The objection was brushed aside. There was no place, the bishop was sternly informed, in a war against an enemy as terrible as Hitler, for humanitarian or sentimental scruples. In February 1945, it was the turn of Dresden to burn. The most beautiful city in Germany was reduced to ashes. So too was much else. By the time the country was at last brought to unconditional surrender in May 1945, most of it lay in ruins. [pages 484-485]

The mention of Otto Dix is fascinating. Despite the bust he had made of Nietzsche, his readings of the philosopher, and his having fought on Hitler’s side at the Somme, he suffered a psychogenic regression towards Tolkien’s side. In the following decades, as we shall see in the final chapters of Dominion, Christian morality would exacerbate and triumph in the collective unconscious of every white man, atheists included.

Dominion, 33

‘Wherever you find them, beat up the Fascists!’

The name derived from the palmy days of ancient Rome. The fasces, a bundle of scourging rods, had served the guards appointed to elected magistrates as emblems of their authority. Not every magistrate in Roman history, though, had necessarily been elected. Times of crisis had demanded exceptional measures. Julius Caesar, following his defeat of Pompey, had been appointed dictator: an office that had permitted him to take sole control of the state. Each of his guards had carried on their shoulders, bundled up with the scourging rods, an axe. Nietzsche, predicting that a great convulsion was approaching, a repudiation of the pusillanimous Christian doctrines of equality and compassion, had foretold as well that those who led the revolution would ‘become devisers of emblems and phantoms in their enmity’. Time had proven him right. The fasces had become the badge of a brilliantly successful movement. By 1930, Italy was ruled—as it had been two millennia previously—by a dictator. Benito Mussolini, an erstwhile socialist whose reading of Nietzsche had led him, by the end of the Great War, to dream of forming a new breed of man, an elite worthy of a fascist state, cast himself both as Caesar and as the face of a gleaming future. From the fusion of ancient and modern, melded by the white-hot genius of his leadership, there was to emerge a new Italy. Whether greeting the massed ranks of his followers with a Roman salute or piloting an aircraft, Mussolini posed in ways that consciously sought to erase the entire span of Christian history. Although, in a country as profoundly Catholic as Italy, he had little choice but to cede a measure of autonomy to the Church, his ultimate aim was to subordinate it utterly, to render it the handmaid of the fascist state. Mussolini’s more strident followers exulted nakedly in this goal. ‘Yes indeed, we are totalitarians! We want to be from morning to evening, without distracting thoughts.’

In Berlin too there were such men. The storm troopers of a movement that believed simultaneously in racism and in the subordination of all personal interests to a common good, they called themselves Nationalsozialisten: ‘National Socialists’. Their opponents, in mockery of their pretensions, called them Nazis. But this only betrayed fear. The National Socialists courted the hatred of their foes. An enemy’s loathing was something to be welcomed. It was the anvil on which a new Germany was to be be forged. ‘It is not compassion but courage and toughness that save life, because war is life’s eternal disposition.’ As in Italy, so in Germany, fascism worked to combine the glamour and the violence of antiquity with that of the modern world. There was no place in this vision of the future for the mewling feebleness of Christianity. The blond beast was to be liberated from his monastery. A new age had dawned. Adolf Hitler, the leader of the Nazis, was not, as Mussolini could claim to be, an intellectual; but he did not need to be.

I don’t know if it is appropriate to call the young Adolf, as in this portrait, an ‘intellectual’ (a word widely used in Europe and Latin America for the thinking classes, but not in the US). But the mature Hitler, the Hitler of the after-dinner talks, was certainly an intellectual compared to any head of state of his time.

I don’t know if it is appropriate to call the young Adolf, as in this portrait, an ‘intellectual’ (a word widely used in Europe and Latin America for the thinking classes, but not in the US). But the mature Hitler, the Hitler of the after-dinner talks, was certainly an intellectual compared to any head of state of his time.

Over the course of a life that had embraced living in a dosshouse, injury at the Somme, and imprisonment for an attempted putsch, he had come to feel himself summoned by a mysterious providence to transform the world. Patchily read in philosophy and science he might be, but of one thing he was viscerally certain: destiny was written in a people’s blood. There was no universal morality. A Russian was not a German. Every nation was different, and a people that refused to listen to the dictates of its soul was a people doomed to extinction. ‘All who are not of good race in this world,’ Hitler warned, ‘are chaff.’

Once, in the happy days of their infancy, the German people had been at one with the forests in which they lived. They had existed as a tree might: not just as the sum of its branches, its twigs and its leaves, but as a living, organic whole. But then the soil from which the Nordic race were sprung had been polluted. Their sap had been poisoned. Their limbs had been cut back. Only surgery could save them now. Hitler’s policies, although rooted in a sense of race as something primordially ancient, were rooted as well in the clinical formulations of evolutionary theory. The measures that would restore purity to the German people were prescribed equally by ancient chronicles and by Darwinist textbooks. To eliminate those who stood in the way of fulfilling such a programme was not a crime, but a responsibility. ‘Apes massacre all fringe elements as alien to their community.’ Hitler did not hesitate to draw the logical conclusion. ‘What is valid for monkeys must be all the more valid for humans.’ Man was as subject to the struggle for life, and to the need to preserve the purity of his race, as any other species. To put this into practice was not cruelty. It was simply the way of the world…

In 1933, the year that Hitler was appointed chancellor, Protestant churches across Germany marked the annual celebration of the Reformation by singing Wessel’s battle hymn. In Berlin Cathedral, a pastor shamelessly aped Goebbels. Wessel, he preached, had died just as Jesus had died. Then, just for good measure, he added that Hitler was ‘a man sent by God’.

Horst Wessel (1907-1930) was a Berlin leader of the NSDAP’s SA, killed by Communists and became a National Socialist martyr. A march he had written the lyrics to was renamed the Horst Wessel Lied and became the co-national anthem of NS Germany. After WWII, the lyrics and tune of his song were made illegal in Germany, his memorial vandalised and his gravestone and remains destroyed. Holland continues: