Gentile Reinfeld vs. Jew Reti

I have said that except for computers the colour of chess is the colour of blood, and that some chess players live more in the world of emotions than in that of cold logic that neophytes observe from the outside. In those emotions, including the thirst to win, the fate of a game is sometimes settled. But from the point of view of the oracle of Delphi I am afraid to say that many players are still children: they don’t know themselves, much less the universe and the gods. Recall how all Fischer read were the Sunday newspaper comic strips, and how Karpov defended the totalitarian regime of his country before the revolutions of 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

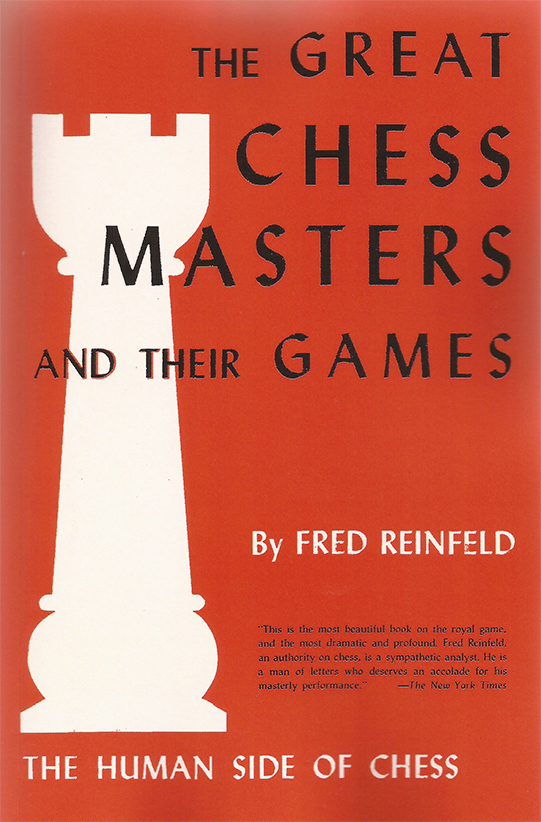

At this point I would like to say something about the chess writer Fred Reinfeld. Although in his time the elements didn’t exist to penetrate the hearts of lost souls, he at least made an attempt to probe them. In Mexico, there is a tendency to value European writers at the expense of Americans. I remember what Octavio Paz said about his grandfather’s library, which was rich in French writers and poor in North Americans. Reinfeld had a humble job as a bureaucrat, sought to move up the social ladder, and managed to commercialise many of his chess books in the United States. But it was in a book by Paz precisely where I read that what is written for money lacks artistic value. Nonetheless, Reinfeld wrote a good book. The Great Chess Masters and their Games: The Human Side of Chess, published in 1952, superior to Masters of the Chess Board by Richard Reti in terms of a didactic vision of what chess is. This statement will sound terrible anathema to those who only know the business side of Reinfeld’s books, but his book shows that Reti omitted the personal element in his analysis of the match between Anderssen and Morphy. I think Reinfeld’s critique of dry schematics, that is, of almost every chess commentator, should be read. I’m not saying reread because books like this are rarely on hobbyist bookshelves. Focusing on the psychological aspect of the champions, Reinfeld tells us: ‘I must confess that I am at a loss to understand why these observations have not been made previously’.

A single example will suffice to illustrate his assessment of why Anderssen lost the match. The German master didn’t fail to understand the hidden laws of chess, the canonical version in Reti’s books. He failed to define his well-thought-out games with Morphy. And he failed because at his age his brain wasn’t as trained to play as his young rival’s. It is sad that Reti’s followers simply repeat the myth of their European mentor without qualms: that Morphy had a secret weapon, his positional knowledge of the open game, the centre and the rapid mobility of the pieces. The truth is that Anderssen understood those principles equally. Reinfeld says something similar about the match between Zukertort and Steinitz, and it is also sad that only because he was not champion the beautiful games of Zukertort, who died two years after his defeat, have been relegated to obscurity.

A single example will suffice to illustrate his assessment of why Anderssen lost the match. The German master didn’t fail to understand the hidden laws of chess, the canonical version in Reti’s books. He failed to define his well-thought-out games with Morphy. And he failed because at his age his brain wasn’t as trained to play as his young rival’s. It is sad that Reti’s followers simply repeat the myth of their European mentor without qualms: that Morphy had a secret weapon, his positional knowledge of the open game, the centre and the rapid mobility of the pieces. The truth is that Anderssen understood those principles equally. Reinfeld says something similar about the match between Zukertort and Steinitz, and it is also sad that only because he was not champion the beautiful games of Zukertort, who died two years after his defeat, have been relegated to obscurity.

For Reinfeld, who wrote in the middle of the last century, the most exciting world championships were those of Steinitz with Zukertort and those of Euwe with Alekhine (remember that Reinfeld published when Botvinnik was already three years as champion). On the matches between Chigorin and Steinitz, the bloodiest in world championship history, Reinfeld wrote:

They had an unrivalled insight into the nature of chess. Whereas the popularizers think of chess as being amenable to order, logic, exactitude, calculation, foresight and other comparable qualities, Steinitz and Tchigorin agreed on one thing: that chess can be, and often is, as irrational as life itself. It is full of disorder, imperfection, blunders, inexactitudes, fortuituous happenings, unforeseen consequences.

It is precisely due to the lack of insight from the fans that a great champion like Lasker has never been understood. If there is one thing that caught my attention about his match with Steinitz, it was that he defended himself in a lost position where he could be left with three pawns less. That happened in the seventh game in which the young Lasker disputed the crown of the mature champion. Steinitz made an eccentricity by placing his knight to the h8 square that ended up being quite expensive.

Misunderstanding the extremely complicated position that emerged, a position analogous to those that would emerge much later in Tal’s games, he became demoralized and lost the next four games, the match and the crown. Reti erred in Masters of the Chess Board by saying that Lasker played badly on purpose to confuse the opponent. It’s obvious that Lasker didn’t want to lose so many pawns in his decisive game with Steinitz. Rather, what Lasker was doing was, as Nimzowitsch would say, ‘heroically defend himself’ in lost positions where most of us players would feel dejected. Intuitively, Lasker did that—something that Nimzowitsch, another dry game theorist, didn’t see either—because Lasker knew that if he flipped a losing position he would have a moral advantage over his opponent.

Reinfeld’s extended book subtitle reads: ‘The Story of the World Champions: Their Triumphs and their Illusions, Their Achievements and Their Failures’. Sometimes in my diary I write things that never appear in the schematic books of Colección Escaques, a notable Spanish publisher of chess books during my adolescence; in the more than dry Informants or in Reti’s aseptic books. On one occasion I wrote: ‘I was peeing in fear’ because of my nerves during a game. I’ve heard that the same thing happens to other players. ‘To the bathroom, to the bathroom, to the bathroom’ a friend told me about his tournament experiences. When I wanted to break the taboo and wrote in the Club Mercenarios newsletter the agonies that I revealed in the previous chapter, Willy de Winter, one of the main chess promoters in Mexico, misunderstood my initiative. At the beginning of the next round he asked me in public ‘How do you feel?’ as if implying that only I suffered from tribulations, when the truth is that many others do. De Winter’s question ignored that my initiative was simply to break one of the taboos in chess literature: to speak as frankly as possible, and in the first person singular, about our emotions when we play. But laymen have been able to see the player’s emotions. In 1922 a London journalist wrote about Alekhine:

He is a hatched-faced blond giant, with a sweep of hair over his forehead, and several inches of cuff protruding from his sleeve. First he rests his head in his hands, works his ears into indescribable shapes, clasps his hands under his chin in pitiful supplication, shifts uneasily in his seat like a dog on an ant-hill, frowns, elevates his eyebrows, rises suddenly and stands behind his chair for a panoramic view of the table, resumes his seat, then, as the twin clock at his side ticks remorselessly on, sweeps his hair back for the thousand time, shifts a Pawn, taps the clock button, and records his move.

This is the agony that the chess player encounters not in a game, but in a single move. This is chess. However, de Winter never talks about his emotions in the chess newsletter that he publishes, despite the fact that fans have seen him rise up like Alekhine; put one of his feet on the chair, elbow on his knee and hand on his cheek when he gets nervous in a tournament. It is evident that strong emotions when playing are suffered by all of us. What I said about avoiding self-knowledge is also exemplified by de Winter with the question he asked me.

The idea of journaling is not only to help us heal the pride that only women have the right to tell their sorrows and to cry. We must make contact with what fans not only silence to others, but to ourselves. Making deep contact with our emotions reconciles us with them and allows us to mature. Many chess players, including some who were child prodigies, have failed precisely because they denied the feminine part in them. They didn’t manage to harmonise their cognitive apparatus with the sentimental part of their psyche, nor did they make a healthy eruption of the magma they suffer in the interior towards the temperate surfaces of reason.[1] The private diary that no one but one reads is part of the cure for this psychic congestion.

Another of my suggestions is that you write a comment about your games, emphasising the ones you have lost. Many chess players have a huge ego. They always find the cleverest excuses for their defeats, and they tend to remember only their victories. They look like turkeys puffed up with pride the day before they are killed for Christmas dinner.

Let us remember how Fischer broke with the tradition of Alekhine and Capablanca of writing only about their victories. In My 60 Memorable Games Fischer spoke with great honesty about his draws and even some of the defeats that hurt him the most. The idea of journaling is to deflate turkey pride and accept our level of play. But like other people’s diaries, your own is a private matter. In my comments about my games I cited some of my emotions, but in the diaries we write even more intimate things than saying that we ran to the bathroom. On the other hand, writing a not so intimate comment about the games we have played, and I did try that in the previous chapter, in addition to being healthy it means that we can photocopy it and distribute it among our friends. It is a great therapy to share with others the reasons why we lost or why we suffered so much during the victories, something that others have confessed to me that also happens to them.

There are other advantages to commenting on our games in writing. When I transcribed and analysed the fifty games that I played in tournaments in the nineties, great surprises occurred. For example, due to the low self-esteem through which I was crossing in 1993, I realised that I had resigned a clearly drawish endgame of rooks with Jorge Martín del Campo. Likewise, in another game where I lost the exchange with black against Fernando Araiza, I suddenly resigned. Ten years later, by putting that same position on Fritz, the machine played a tedious game with itself of more than a hundred moves that ended in a draw, proving that my resigning was foolish. During the live game I hadn’t realised that, with eight pawns on each side, losing the exchange in that closed position didn’t mean a decisive advantage. This was recognised by Fritz from the visual thinking screen where he put the sign ‘equality’ or ‘something better’ and not the ‘clear advantage’ of white in the various positions it played after my resignation. Likewise, for years I blamed my opening choice, a Richter attack that I played against Alberto Escobedo in a French Defence, instead of focusing on a blunder that for some reason my memory failed to register: the real cause of my defeat. I had mistakenly been left under the impression that the now-deceased Escobedo had outdone me cleanly in a defence he knew pretty well. When I put Fritz the position I realised that before the blunder, the game I played with Escobedo was even. In fact, the game that Fritz played with itself also ended in a draw.

It is true that chess is so complicated that we shouldn’t even trust computational analysis as the last word on a position. In Caissa’s magical domain the computer can still do mistakes, as Hal 9000 erred en route to Jupiter by underestimating Dave. However, at a slow pace of play it is generally a good reference to calibrate a complicated position that would otherwise take a lot of trouble to disentangle. This is what Kasparov observed in the first volume about his great predecessors: even a computer would take a long time to decipher that position that emerged in the seventh game of the Steinitz-Lasker match, mentioned above. The Fritz I own is a sophisticated program. I recommend that hobbyists take some private lessons with users of the program before using it. It is a great GM slave who not only plays with us every time we ask him to, but it can be forced to play a specific position to solve our doubts, such as the doubts I had about my games with del Campo, Araiza, Escobedo and many others.

While transcribing, analysing, and even photocopying my comments about my games and sharing them with friends doesn’t level me up, it improves morale. But the knowledge of oneself, to reconcile with the past and with the defeats, is a practice that doesn’t occur to those who focus on variants, those who devour Informants or variants of ChessBase believing that by memorising them they will win. The truth is that I have found them crying in tournaments when faced with reality. It’s very easy to get a player out of his favourite line, which prompts me to the next suggestion.

__________________

(1) See ‘The Eternal Feminine’ in pages 176-180 of my Daybreak. PDF clickable from the sidebar.