Before I continue commenting on the film where Reinhard Heydrich, the ‘iron-hearted man’, is our hero, I would like to clarify what I recently said about Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Yesterday in the comments section, I said:

I put a painting of Goethe because I mentioned him in my previous post about Heydrich. But the abject slavery of the greatest writers to Christianity is more evident in Dante, for obvious reasons; and Cervantes, who considered his masterpiece not Don Quixote but Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda, where Nordic princes travel around various places in the world to end up arriving in Rome, the seat of the Vatican, and get married.

I started the discussion about Goethe because he is mentioned in the film to the detriment of the SS. But if Nietzsche had respect for him, it is precisely because Goethe represents what I called ‘Bridges’ in January, in the context of Wagner’s musical dramas taking us away from Johann Sebastian Bach’s resounding Christianity. In other words, despite the mixture of his pagan The Ring of the Nibelung with the Christian Parsifal, Wagner takes a few steps towards our side of the psychological Rubicon, even if neither Goethe nor Wagner crossed it (indeed, even Nietzsche himself didn’t fully cross it, having failed to read Gobineau).

So I can be charitable with Goethe as long as we place him as a man of his time. He indeed took a few baby steps on the Rubicon although he had a long way to reach the other shore. From this angle, I have nothing against him or Wagner, and those who want to delve deeper into the subject could reread my article ‘Bridges’.

Goethe is considered the greatest figure of German letters, but what motivated me to write this entry is that, if I mentioned the most famous writer in the Spanish language, Cervantes, and the most influential in Italian Christendom, Dante, what could I say about the greatest figure of English letters, Shakespeare?

Just as on Saturday I mentioned Faust as Goethe’s most popular drama, Hamlet is Shakespeare’s most popular play, so I must say a few words about the latter.

In Crusade against the Cross I said that my purpose was to detect and expose the vestiges of Christianity that still inhabited figures considered stellar in the Western tradition, and I pointed out that there were even those residues in the metaphysics that Nietzsche himself had wanted to elaborate. If Nietzsche had followed the command of the Delphic oracle he would have understood these residues and, perhaps, wouldn’t have become psychotic by the end of his life.

Though fictional, Hamlet is a character who, asking himself a thousand questions as he wanders the vast halls of the Danish castle, he also struggles with mental illness. In my article ‘Hamlet’ last year, I implied that the Greek tragedians knew the human soul better than the great writers of Christendom for the simple reason that the latter have lived under the sky of the fourth commandment, honour our parents, and that this prevented them from seeing that some parents drive their children mad. This is so true that I commented in that article that even Voltaire hadn’t broken with that Christian commandment (it was not until the 20th and 21st centuries that a Swiss writer, Alice Miller, repudiated such a toxic commandment).

But in this entry I didn’t want to talk about the trauma model of mental disorders. I want to put Shakespeare on par with Goethe in the sense that their most famous works, Faust and Hamlet, contain strong Christian residues.

Like Goethe, Shakespeare needs to be contextualised.

What could a continental freethinker do in the mid-16th century during the wars between Catholics and Protestants? Become a recluse. A sceptic of Christianity, Montaigne, did exactly that: something that evokes that many contemporary racialists are now recluses because of social ostracism if they dare to come down from their towers. Montaigne impresses me because he was the true representative of the intellectual side of the Renaissance, in sharp contrast to Erasmus who still lived in the thickest medieval darkness (cf. what I wrote about Erasmus in Daybreak).

England was then freer than Montaigne’s France, and that is the background to understanding William Shakespeare. We know that Shakespeare read Florio’s translations of Montaigne and that he was very impressed by him. Kenneth Clark said that Shakespeare was the first great poet of Christendom without religious beliefs.

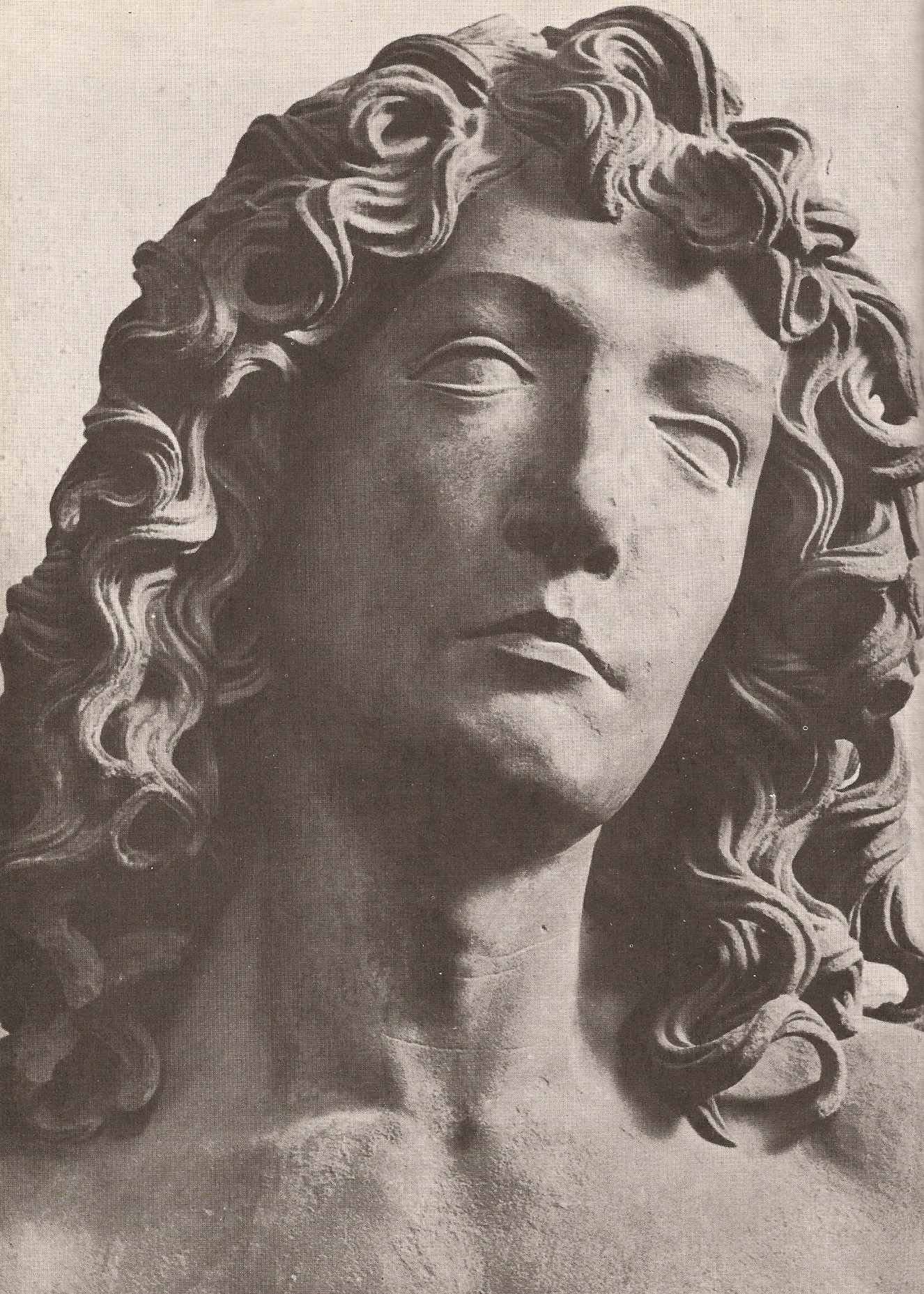

(Left, Hamlet by William Morris Hunt, a 19th century painter.) However, like Goethe with his Faust, this is not entirely accurate. Shakespeare’s Hamlet has to be placed within the matrix of Elizabethan England: a time when Christian doctrine was still taken very seriously, both in its Anglican and Papist versions. Hamlet suffered a schizogenic struggle. He struggled internally with the command of his father’s ghost, from purgatory, to avenge him; but Hamlet couldn’t condemn himself, should he commit the mortal sin of murdering his uncle if he was, after all, innocent: a dilemma with which he struggles internally throughout the play.

(Left, Hamlet by William Morris Hunt, a 19th century painter.) However, like Goethe with his Faust, this is not entirely accurate. Shakespeare’s Hamlet has to be placed within the matrix of Elizabethan England: a time when Christian doctrine was still taken very seriously, both in its Anglican and Papist versions. Hamlet suffered a schizogenic struggle. He struggled internally with the command of his father’s ghost, from purgatory, to avenge him; but Hamlet couldn’t condemn himself, should he commit the mortal sin of murdering his uncle if he was, after all, innocent: a dilemma with which he struggles internally throughout the play.

So despite being influenced by the free-thinking ideas of his time, like Goethe Shakespeare was playing with Christian post-mortem doctrine. Nonetheless, from the viewpoint of my autobiographical trilogy, which tries to fulfil Delphi’s mandate, Hamlet certainly represents a breakthrough in insight: it is the first foray into what we may call the true self (as opposed to the false self: the internal struggles we read in Augustine’s Confessions).

What gives Hamlet such evocative power is that the tragedy doesn’t take place on stage but within Hamlet’s soul. The whole play is a soliloquy, and since I have finished my trilogy these days with a postscript to my own tragedy with my father, I would like to quote a few words from Hamlet’s second scene:

Would I had met my dearest foe in heaven

Or ever I had seen that day, Horatio!

My father!—methinks I see my father.

A couple of minutes of the 1948 film interpretation from this point onwards portrays Hamlet’s inward-spiralling soliloquies very well. Incidentally, I saw that film with my father in 1975: time when he had already mistreated me.