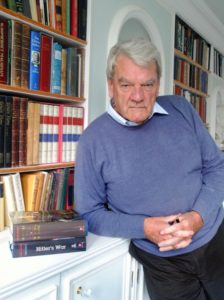

Editor’s Note: Below, excerpts from the third chapter, ‘A Witch in the Family’, of David Irving’s book on Heinrich Himmler (available through Irving’s bookstore here).

______ 卐 ______

Himmler’s missing 1940 diary appeared on the auction block in Munich in 2006; we were languishing that year in a Vienna prison cell, convicted of ‘reviving the Nazi Party’ through views expressed sixteen years earlier. The original is now deposited under glass, like a rare poisonous beetle, in the museum of a medieval castle called Wewelsburg, of which we shall eventually hear more. We know that Professor Michael Wildt worked on Himmler’s 1937 diary in Moscow, and we obtained copies of the 1941 and 1942 diaries from the NA and the same archives.

There is one other trove to be mentioned: the papers of Himmler’s wife and daughter. Years ago, an Englishman won them at an auction in New York. Chaim Rosenthal, a crooked cultural attaché at the Israeli consulate, offered to the naïve Englishman to convey these to the U.K., but hastened back to Tel Aviv instead. He donated them to Tel Aviv university. Upon realising that they were twice-stolen property, the Israeli university quiet properly returned them, though to Rosenthal and not their rightful owner.

* * *

Not every child is blessed to have a school headmaster as a father, although Heinrich Himmler may not have considered it good fortune at the time. Heinrich had been born into such a teacher’s family in Munich, just two hundred and eighty days into the Twentieth Century upon which he was to leave such an indelible mark; some of his ill-starred contemporaries including Hans Frank and Martin Bormann were also born in 1900…

Their ancestral line stretched back over the centuries, its nodes and gridlines populated by a motley cast of businessmen, gendarmes, and schoolmasters. Heini’s own experts would trace them back to before Charlemagne. One of Heini’s female ancestors named Passanquay had been burned at the stake as a witch. Reinhard Heydrich would derive satisfaction from informing him in May 1939 of another unfortunate, Margareth Himbler, of Markelsheim, burned as a witch on Apr 4, 1629…

Having retired at sixty-five with the venerable rank of Geheimrat, or privy counsellor, the professor would die on October 29, 1936, before Heini’s fame had turned to infamy. His wife, Frau Geheimrat Anna, was remembered as a gentle little woman, a churchgoer. ‘She could not have hurt a fly,’ said one who knew her. They had been living on the second floor of No. 6, Hildegard Strasse, when she produced Heini, their second boy, on October 7, 1900… A few months later, in March 1901, they moved to a new apartment above a pharmacy in Liebig Strasse, in a genteel area of Munich.

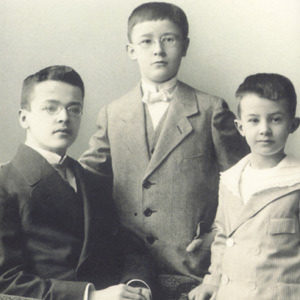

A tall carved statue of Christ stood in the entrance hall—an heirloom left to their mother, and the boys crossed themselves each time before it, just as their parents did. Heini set up an Ahnen-Zimmer, an ancestral shrine, where he spent hours studying his ancestors… The photos show him already wearing the round-eyed glasses which were to become iconic later in his life.

He made many friends at the Gymnasium. One was Wolfgang Hallgarten, three months his junior and son of a New York Jew (but raised as a Lutheran). Heini occasionally visited their home; the boys’ governess Luise Essert discovered his passion for hot chocolate. It was a wealthy, enlightened household. Thomas Mann and Bruno Walter the conductor were among other guests, and the young physicist Werner Heisenberg played his cello within its walls. ‘We knew him from 1910 to 1913,’ wrote Hallgarten of Heinrich Himmler, rising rather notably to his defence in the 1950s, ‘the years when we were all students at the Royal Wilhelm Gymnasium in Munich’… ‘I for my part failed to discover the slightest anti-Semitic streak in him’, reminisced Hallgarten, referring to those shared childhood years at school. For many years he assumed that the fearsome Himmler that people spoke about was a brother, and not the boy he had known…

An older brother, named Gebhard like their father, had been born toward the end of the century which the world had left behind—on July 29, 1898 to be precise. A third son, little Ernst Hermann Himmler, arrived five years after Heini. He was born two days before Christmas in 1905. ‘Ernstl,’ as they called him, married Paula during World War Two, and would disappear on its last day, killed in action. Ernst had joined the Volkssturm, Germany’s ‘Home Guard,’ and when the Soviet Army attacked Berlin’s Charlottenburg district he went out, rifle in hand, to defend the Radio building with the rest of his staff and was not seen again…

An older brother, named Gebhard like their father, had been born toward the end of the century which the world had left behind—on July 29, 1898 to be precise. A third son, little Ernst Hermann Himmler, arrived five years after Heini. He was born two days before Christmas in 1905. ‘Ernstl,’ as they called him, married Paula during World War Two, and would disappear on its last day, killed in action. Ernst had joined the Volkssturm, Germany’s ‘Home Guard,’ and when the Soviet Army attacked Berlin’s Charlottenburg district he went out, rifle in hand, to defend the Radio building with the rest of his staff and was not seen again…

‘If my parents’ house was an extraordinarily liberal, free, quiet one,’ recalled Karl, on trial for his life half a century later, ‘then the Himmler house was that of a strong orthodox Catholic schoolmaster, whose son was brought up strictly and kept very short of cash.’ Karl Gebhardt would accompany Heini throughout his life…

The Himmlers were a church-going family. They prayed together, and stayed together. His parent’s influence remained overbearing. Heinrich was received into the Catholic church on April 1, 1911; he placed in his private papers a printed ‘First Communion’ certificate based on a painting of Christ at the Last Supper; he went frequently to Mass and received Holy Communion kneeling at his father’s side, he celebrated his own family name-days and those of the Bavarian royal family. When Gebhard fell dangerously ill with pleurisy in 1914, they promised a pilgrimage to Burghausen and a special Mass if he recovered, and they kept their promise. Heini went to church every morning, and mentioned each visit in the diary in case the Lord had not caught sight of this little lamb attending His House…

This was not without its effect on the impressionable youngster. How he envied Gebhard when he turned on July 29 and signed up for the Landsturm, the reserve: ‘O, to be out there with the rest of them!’—meaning the fighting front. Instead he stayed behind, teaching Ernstl to swim, and went for walks to more churches and monasteries with his pious mother. Once they climbed up to see the church atop the Marienburg; Heini counted the steps on the way down, to where in 1143 a Cistercian monastery had been founded: 265 steps, he found. He entered the number in his diary…

* * *

Young Heini applied for a commission in the navy, we are told, but the navy turned him down, because of his poor eyesight… As Germany’s war fortunes declined, the request was refused. Heini left school on October 8, 1917 and began training as a Fahnenjunker with the 11th Bavarian Infantry Regiment ‘Von der Tann’ in Regensburg. He formally entered military service on January 2, 1918. Still of indifferent physique, he found the training demanding…

With the war over… his godfather Prince Heinrich had been killed in action. In Bavaria the Communists had seized power, overthrown the Wittelsbach monarchy, and established a republic under the Jew Kurt Kamonowsky, better known as Kurt Eisner.

He began to sport a small toothbrush moustache, and this was no accident. Men who had entered the war with handlebar moustaches had trimmed them to fit the gasmask issued after they came under mustard-gas attack. The toothbrush moustache became the unstated badge of the western front veteran… He moved to Munich, where he would start his further education and eventually become involved, much against his will, in politics.

* * *

As for his father, we have a final glimpse of this extraordinary pedagogue. By now nicknamed Quince Face by his pupils, because of his jaundiced pallor, he retired with high honours aged sixty-five in 1930. In 1989 the writer Alfred Andersch published a semi-autobiographical novel, The Father of a Murderer. It was a fictional account of a school class dominated by a terrifying and sadistic Old Man Himmler, a class ending with Alfred’s summary expulsion…

Heini’s father died in 1936. He had never been the pedagogic sadist depicted by Andersch and his profitable pen, but a stern man of quiet discipline and abiding religious fervour, inspired by a genuine pietas bavarica. The Germans however like their comfortable stereotypes: The Andersch novel was filmed and is now required reading for German schoolchildren.

Stereotypes will continue to blur the image of Heinrich Himmler, confusing though it is. They choke history like bindweed in a jungle, through which we have first to hack and clear a path.

THERE WAS ONE OVERHANGING PROBLEM, the growing left-wing unrest in Bavaria. The army might soon have him doing night patrols as a reservist. ‘Dear Mother, Dear Father,’ he wrote on November 6, 1919. ‘Today you get your promised letter. Thanks a lot for your dear packages. The one with coat and fur jumpers arrived this morning. Gebhard collected the other at the post office this afternoon. Again, dear Mother, thanks a lot. After all, your boys are a bothersome pair. The possibility exists that they will call us up in a few days’ time…’

THERE WAS ONE OVERHANGING PROBLEM, the growing left-wing unrest in Bavaria. The army might soon have him doing night patrols as a reservist. ‘Dear Mother, Dear Father,’ he wrote on November 6, 1919. ‘Today you get your promised letter. Thanks a lot for your dear packages. The one with coat and fur jumpers arrived this morning. Gebhard collected the other at the post office this afternoon. Again, dear Mother, thanks a lot. After all, your boys are a bothersome pair. The possibility exists that they will call us up in a few days’ time…’