‘Universal education is the most corroding and disintegrating poison that liberalism has ever invented for its own destruction’.

—Hitler

‘Universal education is the most corroding and disintegrating poison that liberalism has ever invented for its own destruction’.

—Hitler

I would like to add something to what I said last week about my nephew (see also this thread from earlier this year). In December 2022 I posted an entry containing this paragraph:

I wonder if there is anyone on the planet willing to raise, at least, one Aryan boy and one Aryan girl and educate them strictly in NS, with all that such an education would entail. If there is anyone who harbours this fantasy please contact me.

I received no email response, which can be interpreted in two ways. Either no one who visits this site was interested in raising a child, or some Europeans who visited it were interested but fearing the soft totalitarian state their country suffers from (no First Amendment) didn’t want to contact me. I conjecture it is the former, which brings back that we are in the darkest hour for the white race.

Years ago, in the comments section, I said that a woman proposed to me a quarter of a century ago and I had refused. She is not an Aryan but a mudblood like me, although by Mexican standards she is considered white (like me). Curiously I have continued dealings with her, though only as a friend. I mention her a lot in my trilogy of autobiographical books.

Since I learned a very hard lesson with my nephew, I now feel like proposing marriage to this woman, if only with the idea of adopting an Aryan child to raise him as the Gods command. Likely, she will now be the one to say no, but I have to at least give it a try.

What is not clear to me, even supposing she agrees, is the question of the children this child educated with the true Gods would meet. Preventing this home-schooled boy from watching television; from owning a mobile phone; from listening to degenerate music or going to degenerate parties is one thing. Preventing him from seeing children his age is another.

I am reminded of a curious anecdote from 1988 when children from my parents’ music school went to Cuba to give concerts (Cuban children also showed off). The Cuban authorities didn’t allow, even for a moment, the two groups to mix to avoid any psychological contamination of the little Cubans with rich but decadent bourgeois lifestyles. But of course: the little Cubans played among themselves. Even supposing my dream came true, and I could raise an Aryan child, with whom could he play?

There are pure Aryans in Mexico (left, a Mennonite girl in Chihuahua, Mexico). Will I have to move next door to a Mennonite community for my adopted child to play with uncorrupted Aryans? Buying a large mansion next to them could only be done if I do a business that has to do with the falling dollar (a big ‘if’ that is not certain to happen!). And even then there would be some tension as the Mennonites are like 19th-century Christians, and my female friend goes to mass every day (although she is so understanding that she doesn’t object to my anti-Christianity).

There are pure Aryans in Mexico (left, a Mennonite girl in Chihuahua, Mexico). Will I have to move next door to a Mennonite community for my adopted child to play with uncorrupted Aryans? Buying a large mansion next to them could only be done if I do a business that has to do with the falling dollar (a big ‘if’ that is not certain to happen!). And even then there would be some tension as the Mennonites are like 19th-century Christians, and my female friend goes to mass every day (although she is so understanding that she doesn’t object to my anti-Christianity).

How difficult it is to have a normal life during what the Indo-Aryans called Kali Yuga! Before making a decision, what are the chances for someone who wants to educate his child properly? Is there a place in the entire world where it is even possible for a white child to live among uncontaminated white children?

Before commenting further on Simms’ book, I would like to say something about my trilogy, which I am re-reading as a preliminary to translating it.

Yesterday I looked through some trilogy pages about my nephew who disturbed me, with whom I share the property where I live with his mother, my sister.

It was he who, when he was a boy of six, invented the nickname ‘Chechar’ and, since he loved me so much, everything pointed to the fact that I could raise him as a son insofar as my sister was a single mother.

Now he is a man of twenty-two, and he has not a single atom of my ideals: nothing, absolutely nothing of the four words, let alone the fourteen. Moreover, like the rest of my nephews and the people of his generation, he is a degenerate as far as culture is concerned. To give just a few examples: being straight he has painted his nails, has always listened to degenerate music and hangs out with his degenerate friends everywhere, constantly coming home in the wee hours of the morning after attending degenerate parties. Unlike Hitler, the nephew eats the flesh of mammals that were tormented in slaughterhouses and, although I gave him my trilogy, he doesn’t read it and I doubt he ever will.

The reason for all this is simple. Unlike Jane Austen’s world, when the heir was the first-born male, in our world, upbringing is done by unwed mothers. And the first thing these little women do is to hand their child over to the clutches of the System so that the System ‘educates’ him.

I could do nothing for my nephew’s education because of the lack of financial means. And even if I had them, where could I take him to school in the West? Even if legally the patria potestas had belonged to me, in the country where we live I would have had to isolate him from children his age, schools, television and he would never have had a mobile phone.

The home library would have been his refuge, home-schooling would have been applied to him and films would have to be almost all in black and white, allowing him to watch only one of them on Sundays. But in that hypothetic castle of purity, which children would he get along with? I would have to be a millionaire to move to an Eastern European country where the Gomorrahite culture is still absent. In this scenario, my sister would have had no say because I, and only I, would have the financial means to make these decisions.

But even a wealthy priest of the holy words would have had difficulty educating him. Country children in the less polluted places of Eastern Europe could begin to be contaminated by possessing, for example, mobile phones: a small window that normalises the world of Gomorrah, and so on.

It has been painful to watch the process of how a pure mind, like the one my nephew had as a child, becomes debased and one can do nothing about it. Is it understandable why I fantasise about mushroom clouds above the major cities of the West? To return to Austen’s world Kalki must first come…

against the Cross, 3

When one delves deeply into Nietzsche’s biography, curious anecdotes come to light that would be hard to imagine for those who are only familiar with his late writings.

Much has been said, for example, about the friendship between Richard Wagner and Nietzsche. But few know that Wagner was born in 1813: the year Nietzsche’s father was born. When Nietzsche was a little boy playing with his sister Elisabeth with tin soldiers and the porcelain figure ‘Squirrel King’ was executing rebels, the revolutionary Wagner was in serious trouble with the king and his life was spared because he was a conductor. The still-small Nietzsche was on the side of the rulers in his Christian kingdom. There were to be no revolutions.

When Nietzsche would later write about his life, he didn’t remember his home in Röcken except for the image of the parish priest, the father, whom he continued to idealise even after he had finished The Antichrist. Indeed, since his father had died when Nietzsche was four years old, the memories of Prussian discipline the priest had meted out to him, in which the little boy would furiously retreat to the toilet to rage alone, were left out of his memory (his mother would later tell some anecdotes about her young son’s life). The idealisation of the parish priest was such that, in the words of Werner Ross, ‘Nietzsche was to merge with his father to form a single figure with him’.

In the family it was taken for granted that little Fritz would become a clergyman like his father. His mother, who put him to bed, told him: ‘If you go on like this, I’ll have to carry you to bed in my arms until you study theology’. Fritz was an obedient child who knew several Bible passages and religious songs by heart so that his schoolmates called him ‘the little shepherd’, who was impressed above all by religious music.

But since the pietistic oppression was a thorn his body began to rebel. In 1856, when Fritz was already a dozen years old, he began to suffer from head and eye ailments. Although he received special holidays for this reason, from that age he would always suffer from these psychosomatic complaints (which would only be alleviated thirty-two years later, with the catharsis of writing several books in a few months, including The Antichrist).

The young Fritz would sneak into the cathedral to watch the rehearsals of the Requiem and was shocked to hear the Dies Irae. At the age of fourteen he entered the famous school in Pforta, where he received an excellent humanistic education and his love of music increased, although he continued to suffer from severe headaches.

At Schulpforta he even attempted a Mass for solo, choir and orchestra, and at the age of sixteen, he sketched a Misere for five voices. At seventeen the parson’s son was ready to die to meet Jesus, and when another of his friends trained in Prussian education (broken in like a horse I’d better say!) received the conformation, he wrote: ‘with the earnest promise you enter the line of adult Christians who are held worthy of our Saviour’s most precious legacy’.

Nevertheless, the first signs of rebellion, albeit still unconsciously, began to spontaneously sprout in his seventeenth year. In the Easter holidays of 1862, the student Nietzsche wrote to the union of his friends, under the title Fate and History, a prophetic declaration: ‘But, as soon as it would be possible to overthrow the entire past of the world with a strong will, we would enter the roll of the independent Gods’.

Schulpforta’s severe discipline had been a kind of convent to train not only Nietzsche but also the rest of the inmates, but the adolescent Nietzsche, always at the head of the class and lacking an esprit de corps, was such a good boy that in cases of insubordination he sided with the teachers.

In his thick volume (866 pages in the edition I have) Ross comments that the letters of the pupil Nietzsche are empty of content, in the sense that his inner life was still hermetically sealed off from him. Nevertheless, when the lad Nietzsche left Schulpforta on 7 September 1864, close to his twentieth birthday, and the following month went to study theology and classical philology at the University of Bonn, thanks to his Prussian education he already had the resources for a premature doctorate.

against the Cross, 2

Lutheran father (1813-1849).

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was born on 15 October 1844 in the small town of Röcken, near Lützen in Thuringia. Formerly part of the kingdom of Saxony, it was annexed to Prussia in 1815. Nietzsche was the first-born son of the local Protestant pastor, Karl Ludwig Nietzsche (pictured above), who at the age of thirty had married a woman of seventeen. A year after the wedding, Friedrich was born, followed a couple of years later by his sister Elisabeth (Nietzsche’s younger brother was born afterwards, but died at the age of two). What is important to report is that, among the ancestors of the future philosopher, on both the paternal and maternal sides, there were several generations of theologians.

The main biographies on which I will rely for this biographical series are the very voluminous treatises by Curt Paul Janz and Werner Ross. The latter, who unlike Janz writes with humour, mentions that exactly at the moment when Nietzsche was born the bells were ringing for the king’s birthday service. The parson’s eyes filled with tears as he uttered: ‘My son, on this earth you shall be called Friedrich Wilhelm in memory of my royal benefactor, for you were born on his birthday’. He added that his son would be so-called because that is what Luther’s Bible said. Friedrich Wilhelm IV, by the way, was no friend of the ideals of the French Revolution. Although benevolent, through the Holy Alliance he longed for a return to feudal times even with knights, orders and castles.

Little Friedrich Wilhelm was instilled from the outset with the messianic consciousness of being a son of the medieval king and a son of God. To use my language, I would say that Nietzsche was a slave to parental introjects. So much so that, decades later, when he suddenly fell into a state of psychosis and his friend Overbeck came to his rescue in Turin, he realised that only by telling the disturbed man that royal receptions awaited him, did Nietzsche obey to leave Italy. And when somewhat later Langbehn accompanied Nietzsche on his walks in the asylum at Jena in Germany, he said: ‘He is a child and a king; he must be treated as the son of a king that he is. That is the only correct method’.

But in this psychological study I’m getting too far ahead of myself. Let’s go back to his childhood. The thing is that, like Kant, Nietzsche was brought up in pietism. But Kant’s defence mechanism was to shut down all his emotions and he tried to do philosophy as a sort of Mr Spock through pure reason, like a soulless computer. Nietzsche’s defence mechanism against severe pietism would be the diametrical opposite: the mythopoetic explosion of emotions, as we shall see in this series. What we must now tell is that the little Nietzsche was not allowed, in such a Prussian upbringing, to vent his emotions, let alone his anger. Janz’s multi-volume biography informs us of this:

As soon as the eldest son began to talk a little, the father took to spending some of his free time with him. The child did not disturb him in his study cabinet, where, as the mother writes, gazed ‘Silently and thoughtfully’ at the father while he worked. But it was when the father ‘fantasised’ at the piano that the child was most enthusiastic. Already at the age of one year, little Fritz, as everyone called him, would sit in his pram on such occasions and pay attention to his father, completely silent and without taking his eyes off him. However, it cannot be said that during these early years, he was always a good and obedient child. When something did not seem right to him, he would lie on the ground and kick his little legs furiously. The father, it seems, proceeded against this with great energy, despite which the child must have continued for a long time to cling to his stubbornness whenever he was denied anything he wanted; but he no longer rebelled, but, without a word, retired to some quiet corner or to the lavatory, where he bore his anger alone.

Unlike what Alice Miller wrote about little Fritz in The Untouched Key, Janz didn’t suspect that the severe pietistic upbringing might have been abusive.

When Nietzsche was four years old his father died, perhaps of a stroke (it is not clear that the Nietzsche family’s claim that this was due to his falling down the stairs is true). The family moved to Naumburg and Fritz found himself, from then on, as the only male in a household of women: his mother, grandmother, two aunts and younger sister.

The adult women were to teach pious Christian virtues to little Fritz.

Note from June 27, 2024: I think I overdid it with the Sleeping Beauty thing (due to the sins of Disney Studios). It’s certainly great for kids to watch it, even in an ethnostate. Thus, my 11th recommendation would be Sleeping Beauty (1959).

I have added bold to the three films I recommend most: all based on Jane Austen’s novels. Three months ago I wrote:

I left the previous posts for a few days without adding new ones because it is of some importance that at least some visitors to The West’s Darkest Hour find out that in the racialist forums a troll is impersonating me supported by… the moderators! But I made magnificent use of the time to finish the last few pages of the third book of my trilogy. So—

Thanks, Brad!

Thanks Jewish troll!

______ 卐 ______

“L’art pour l’art values must be transvalued to Art practiced in conformity with the cultural task” —Francis Parker Yockey (rephrased).

In 2013 I posted a list of what were, at the time, my ten favourite films and last year I confessed that, having taken my vows as a priest of the sacred words, I could no longer watch many of the 50 films I once loved. So I would like to compile a new list of ten films that, if I were to adopt an Aryan son,[1] I would allow him to watch. Sorted by the year they were released, this new list would be:

1. Beauty and the Beast (1946)

2. Hamlet (1948)

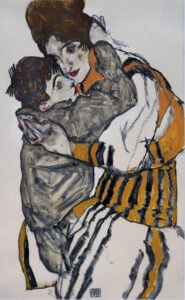

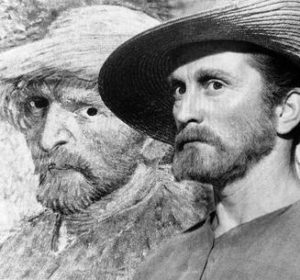

3. Lust for Life (1956)

4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

5. Death in Venice (1971)

6. Sense & Sensibility (1995)

7. Indictment: The McMartin Trial (1995)

8. Pride & Prejudice (1995 TV series)

9. Pride & Prejudice (2005 movie)

10. Spotlight (2015)

In the case of the first on the list, it is only because of our interpretation of it that I recommend it. Why I put the second one on my new list, which also appears on my 2013 list, is explained by clicking the link above on Hamlet.

But the third one doesn’t appear on my old list. As I own several Vincent van Gogh books, including a huge illustrated one with his complete works, I recommend Lust for Life because, like Hitler, it seems to me essential that the Aryan who wants to save his race from extinction should make deep contact with the art of painting; and the film, based on an entertaining novel that I read, transports us to the places where brother Vincent lived.

But the third one doesn’t appear on my old list. As I own several Vincent van Gogh books, including a huge illustrated one with his complete works, I recommend Lust for Life because, like Hitler, it seems to me essential that the Aryan who wants to save his race from extinction should make deep contact with the art of painting; and the film, based on an entertaining novel that I read, transports us to the places where brother Vincent lived.

Of articles by intellectuals, John Gardner was the first white nationalist I ever read, in 2009, when I returned to this continent from Spain. In one of his TOQ Online articles Gardner said that 2001: A Space Odyssey managed to put the white man’s aesthetics in its place, which I agree with.

Why I include Death in Venice is guessed at in ‘Transvaluation Explained’ and ‘Puritanical Gomorrah’ in my book Daybreak, but most of my list (#6, #8 and #9) concerns films about Jane Austen’s novels. As for the remaining ones, Indictment and Spotlight, just click on the links in the above list to see why I include them.

Note that, unlike my 2013 list, my criteria is no longer to include films based on their artistic quality but on what Yockey says above. The film about the medieval monk Andrei Rublev for example is highly artistic to the true connoisseur of cinematic art. But I wouldn’t show it to my son, at least not until he had developed a sufficiently anti-Christian criterion to realise that the pagan Russians should never have embraced a religion of Semitic origin.

I can say something similar about Sleeping Beauty, which appears on my previous top ten list, although this is a fairly tale. It makes me a little nervous that at the climax Maleficent invokes all the powers of Lucifer, and that Prince Philip’s coat of arms bears a Christian cross. A child, of course, wouldn’t notice that. But what Walt Disney had done, collaborating with the American government in times of anti-Nazi propaganda through another of his cartoons caricaturing the Third Reich, I cannot forgive.

Likewise, in my new list I didn’t include 1968’s Planet of the Apes which was on the old list because a child shouldn’t see a black astronaut next to a good-looking Aryan actor like Charlton Heston. The same I must say about another of my favourites that I removed from the old list: Artificial Intelligence, where in the first scene the Jew Spielberg puts a compassionate Negress in front of a huge team of scientists who want to design a robot child with real feelings.

The 1977 film Iphigenia was also taken off my list. Although Iphigenia is a masterful adaptation of Euripides’ tragedy many of the actors, unlike the hyper-Nordic Homeric Greeks, are already mudbloods (of course: the film’s actors were contemporary Greeks!). A boy brought up in National Socialism ought not to be fooled by such images.

If someone asks me now, after taking my vows, which of the above list of ten are now my favourite films, they will be surprised to learn that they are all three based on Austen’s novels. That’s exactly the right message of sexual courtship that Aryans, young and old, should see on the big and small screens if we have the fourteen words in mind.

_________

[1] Although the lad I was doesn’t look too bad in the Metapedia picture, as a priest I can’t sire because my bloodline is as compromised as the Greek actors mentioned above.

Yesterday I ended my post by mentioning the word introject. Like all other cultures, the West is in a very primitive state as far as self-knowledge is concerned. If we take ancient Delphi as a paragon of Aryan wisdom, even the most prominent western thinkers and philosophers of the Christian Era have been but slaves to what I have metaphorically called ‘Semitic malware’ (Judeo-Christianity): the introjects of their parents and educators. I only discovered this in my own mind when, well into my sixties, writing a passage in my third autobiographical book, I was astonished to discover that my mind had, literally, been programmed with Christian introjects since childhood. The details I explain there but suffice it to say here that, before that passage in my last book, I was under the impression that I had been a relatively free and moral agent—precisely the Christian belief in free will—, and that my father’s influence wasn’t as absolute as, now, I am astonished to acknowledge.

But in this entry, I don’t want to talk about autobiography but about biographies. In my 2021 post, ‘On Shelob’s Lair’, I had said that Francis Bacon regarded metaphysical philosophers as weavers of cobwebs. Now I would like to delve a little deeper into Immanuel Kant’s biography.

This German was born in 1724 in Königsberg, which was East Prussia: territories Germany lost after WW2. If the so-called philosophers were lovers of wisdom, as the etymology of the word philosophy says, Prussia would still be part of a German Reich. We can already imagine a world where, instead of metaphysical cobwebs, the great philosophers of German idealism, starting with Kant, would have devoted themselves to what Gobineau (1816-1882) would eventually devote himself to: the study of the races. But I am getting ahead of myself.

This German was born in 1724 in Königsberg, which was East Prussia: territories Germany lost after WW2. If the so-called philosophers were lovers of wisdom, as the etymology of the word philosophy says, Prussia would still be part of a German Reich. We can already imagine a world where, instead of metaphysical cobwebs, the great philosophers of German idealism, starting with Kant, would have devoted themselves to what Gobineau (1816-1882) would eventually devote himself to: the study of the races. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Kant was educated in the stern spirit of Protestant pietism: first by his mother, a pious woman, and then at the Collegium Fridericianum, famous as a pietistic school. During 1740-1746 the lad Kant continued to be brainwashed with theology at the University of Königsberg, where he was greatly influenced by Christian Wolff. If we keep in mind what was said about the role played by the mother in the previous entry, it becomes clear that from an early age the introjects are a kind of building blocks that form a psychic edifice: the structure of a mind in the making. There is no point in giving the details of Kant’s life as a young man because it is clear that his mind was already Christianly structured from an earlier age.

In his late thirties, it is important to mention that Kant wrote Der einzig mögliche Beweisgrund zu einer Demonstration des Daseins Gottes (The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God). Since the young philosopher lived during the Age of Enlightenment, although he never wanted to destroy metaphysics, he did want to put it on new critical foundations. This reminds me that a well-known proponent of the American racial right once called himself a ‘neo-normie’. Kant’s metaphysics was actually a ‘neo-theology’, as we are about to see.

Kant worked for many years on his major work, Critique of Pure Reason, published in 1781 (he died in his hometown in 1804). But what is ‘metaphysics’ according to Kant? Kant simply starts from the conceptions of his time, when philosophy had been trying to become independent of theology as an infant tries to individuate himself before a schizogenic mother. This is so true that Kant himself declares that the contents of metaphysics are no more and no less than the contents of Christian theology. He writes that the ‘inevitable tasks of pure reason are God, freedom and immortality’ (B7). And later he reiterates: ‘Metaphysics has as the specific aim of its investigation only three ideas: God, freedom and immortality’ (B 395).

It couldn’t be clearer: due to the introjects of his early age, the mature philosopher remains the servant of the Christian theologian. (A philosopher of a true age of enlightenment would use the plural to refer to providence, as he would be a man who has already transvalued the monotheistic values of Judeo-Christianity to the Gods of the Delphic inscription.) It doesn’t matter that in his first Critique Kant concludes that metaphysics, as a science, is not possible. The fact that he even returns to the same triad—God, the immortality of the human soul and freedom—when he already writes about ‘practical reason’ speaks for itself. Kant even states: ‘I had therefore to do away with knowledge to make room for faith’ (B XXX).

As I said in ‘Shelob’s Liar’, Kant’s prose is abominable. This major spider was a creature who never successfully rebelled against maternal and scholastic introjects. Even his so-called pure, a priori knowledge was a conception of metaphysics that was rooted in the Cartesian approach and Leibniz’s analytical judgements: a type of metaphysics already removed from the Aristotelian tradition. Let us not forget that, among Christian Wolff’s disciples, there were several 18th-century philosophers, including Kant.

Quite apart from the fact that the obscurantist prose of the exponents of German idealism is intolerable to any sane reader, my point is obvious. The human mind is a structure. Our parents and guardians lay the bricks of the structure that will become our egos, against which it’s very difficult to rebel successfully. Recall the quote from Margaret Mahler in the previous entry, who in analysing the psychology of toddlers discovered that interpersonal relationships are internalised within the ego or what we call the Self. Once internalised, we are slaves to what we have been calling ‘parental introjects’, even the so-called great philosophers.

The first cousin

If Kant, the greatest German philosopher of the so-called Age of Reason, was a creature of mom’s introjects, what could a little Mexican do in the face of the introjects of an even more engulfing mother than a pietistic one raising her child with Prussian ethics?

I invited Marco’s cousin again, who came to my house this very day that I’m writing, whom I won’t mention by name and surname because, given that the name ‘Marco’ I have used is real, and that the only person who visits him in his cobwebbed house is his cousin, I don’t want some Spanish-speaking person in the curious country where I live to find out, through Google, that I’ve been writing about them.

Anyway, I hope tomorrow to continue unravelling this bizarre psychodrama with another entry.

It’s curious, but these days I have been thinking that what was missing for my worldview to be complete was a critique of the traditional pedagogical system (which, by the way, contributed greatly to destroying my adolescent life). And today, in the same chapter of the Heydrich quote I posted yesterday, I come across this passage from Savitri Devi:

The absolute rejection of ‘free and compulsory’ education—the same for all—is another of the main features that bring the society that Adolf Hitler dreamed of establishing, and already that of the Third Reich itself, closer to the traditional societies of the past. Already in Mein Kampf the idea of identical education for young men and women is rejected with the utmost rigour.

It isn’t possible to give the same education to young people whom Nature has destined to different and complementary functions. Similarly, one cannot teach the same things, and in the same spirit, even to young people of the same sex who, later on, will have to engage in unrelated activities. To do so would be to burden their memory with a heap of information which they, for the most part, have no use for while, at the same time, depriving them of valuable knowledge and neglecting the formation of their character.

Later on, Savitri continues:

Hitler considered the superficial study of foreign languages and the sciences to be particularly useless for the great majority of the sons (and even more so for the daughters) of the folk… But there is more, and much more. In a European society dominated by its Germanic elite, such as the Führer would have rebuilt it (if he had been able), education, culture and even more the practical probability of advanced spiritual development, had to regain the secret character—properly initiatory—which they had had in the most remote antiquity, among the Aryan peoples and others: the Germans of the Bronze Age as well as in the Egypt of the Pharaohs, and India. They were to be reserved for the privileged.

And finally:

The secrecy of all science in the future Hitlerian civilisation and the efforts already made under the Third Reich to limit, as far as possible, the misdeeds of general education—that ‘most corrosive poison’ of liberalism—evoke the curse that, thousands of years ago and in all traditional societies, was aimed at all those who would have divulged, especially to people of impure blood, the knowledge which the priests had given to them.

Can you see why the science educators who used TV for the masses, Bronowski and Sagan, were wrong on this point?

Editors’ note: To contextualise these translations of Karlheinz Deschner’s encyclopaedic history of the Church in 10-volumes, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, read the abridged translation of Volume I. In the previous chapter, not translated for this site, the author describes the high level of education in the Greco-Roman world before the Christians burned entire libraries and destroyed an amazing quantity of classical art.

Editors’ note: To contextualise these translations of Karlheinz Deschner’s encyclopaedic history of the Church in 10-volumes, Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums, read the abridged translation of Volume I. In the previous chapter, not translated for this site, the author describes the high level of education in the Greco-Roman world before the Christians burned entire libraries and destroyed an amazing quantity of classical art.

Since the time of Jesus Christianity has taught to hate everything that is not at God’s service

The Gospel was originally an apocalyptic, eschatological message, a preaching of the imminent end of the world. The faith of Jesus and his disciples was, in this respect, firm as a rock, so that any pedagogical question lacked any relevance for them. They did not show the slightest interest in education or culture. Science and philosophy, as well as art, did not bother them at all.

We had to wait no less than three centuries to have a Christian art. The ecclesiastical dispositions, even those enacted in later times, measure artists, comedians, brothel owners and other types with the same theological standard.

Soon it was the case that the ‘fisherman’s language’ (especially, it seems, that of the Latin Bibles) provoked mockery throughout all the centuries, although the Christians defend it ostensibly. This, in despite Jerome and Augustine confess on more than one occasion how much horror is caused by the strange, clumsy and often false style of the Bible. Augustine even said it sounded like stories of old women! (In the 4th century some biblical texts were poured into Virgil hexameters, without making them any less painful.) Homines sine litteris et idiotae (illiterate and ignorant men), thus the Jewish priests describe the apostles of Jesus in the Latin version of the Bible.

As the Kingdom of God did not come upon the Earth, the Church replaced it with the Kingdom of Heaven to which the believers had to orient their entire lives. This meant according the plans of the Church; for the benefit of the Church, and in the interest of the high clergy. For whenever and wherever this clergy speaks of the Church, of Christ, of God and of eternity, it does so solely and exclusively for their own benefit. Pretending to advocate for the health of the believer’s soul, they thought only of their own health. All the virtues of which Christianity made special propaganda, that is, humility, faith, hope, charity, and more, lead to that final goal.

In the New Testament it is no longer human pedagogy what matters, which is barely addressed. What is at stake is the pedagogy of divine redemption.

In the work of Irenaeus, creator of a first theological pedagogy, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Gregory of Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa, the idea of a divine pedagogy is often discussed and God becomes the proper educator. Ergo all education must, in turn, be engaged in the first and last line of God and this must be his role.

That is why Origen teaches that ‘we disdain everything that is chaotic, transient and apparent and we must do everything possible to access life with God’. Hence, John Chrysostom requires parents to educate ‘champions of Christ’ and that they should demand the early and persistent reading of the Bible. Hence, Jerome, who once called a little girl a recruit and a fighter for God, wrote that ‘we do not want to divide equally between Christ and the world’.

‘All education is subject to Christianization’ (Ballauf). Nor does the Doctor of the Church Basil consider ‘an authentic good he who only provides earthly enjoyment’. What was encouraged is the ‘attainment of another life’. That is ‘the only thing that, in our opinion, we should love and pursue with all our strength. All that is not oriented to that goal we must dismiss as lacking in value’.

Such educational principles that are considered chimerical, or ‘worthless’ (everything that does not relate to a supposed life after death), find their foundation even in Jesus himself: ‘If someone comes to me and does not hate his father, his mother, his wife, his children, his brothers, his sisters and even his own life, he can not be my disciple’.

How many misfortunes such words have been sowing for two thousand years…

To save the white race from extinction it is not enough to start using the Semitic words that our Christian parents instilled in us as insults to Neo-Christian Aryans. We also have to make a destructive critique of what we have inherited from the secular world in the West. I have said that, if theology has been the wicked party for the West (tomorrow I’ll resume Deschner’s chapter on St Augustine), philosophy has been the stupid party. On Plato, I have little to add about the stupidities of his philosophy to what has already been said in the previous article of this series. But I still would like to say something.

To save the white race from extinction it is not enough to start using the Semitic words that our Christian parents instilled in us as insults to Neo-Christian Aryans. We also have to make a destructive critique of what we have inherited from the secular world in the West. I have said that, if theology has been the wicked party for the West (tomorrow I’ll resume Deschner’s chapter on St Augustine), philosophy has been the stupid party. On Plato, I have little to add about the stupidities of his philosophy to what has already been said in the previous article of this series. But I still would like to say something.

In the section of Durant’s book, ‘The Ethical Problem’, Plato puts Thrasymachus discussing with Socrates. I must confess that I find quite irritating the figure of Socrates, with his eternal questions always putting on the defensive his opponents. If I had walked on the streets of Pericles’ Athens, I would have told Socrates what Bill O’Reilly told Michael Moore when he met him on the street: that he would answer his questions to Moore as long as he in turn answered O’Reilly’s questions. Otherwise we are always on the defensive against Socrates/Moore.

On the next page, Durant talks about the Gorgias dialogue and says that ‘Callicles denounces morality as an invention of the weak to neutralize the strength of the strong’. In the next section of the same chapter Durant quotes the Protagoras dialogue: ‘As to the people they have no understanding, and only repeat what their rulers are pleased to tell them’. Some pages later Durant quotes one of the passages in which I completely agree with Plato:

The elements of instruction should be presented to the mind in childhood, but not with any compulsion; for a freeman should be a freeman too in the acquisition of knowledge.

Knowledge which is acquired under compulsion has no hold on the mind. Therefore do not use compulsion, but let early education be rather a sort of amusement; this will better enable you to find out the natural bent of the child.

But several pages later Durant tells us that ‘the guardians will have no wives’ and about empowered women, he adds:

But whence will these women come? Some, no doubt, the guardians will woo out of the industrial or military classes; others will have become, by their own right, members of the guardian class. For there is to be no sex barrier of any kind in this community; least of all in education—the girl shall have the same intellectual opportunities as the boy, the same chance to rise to the highest positions in the state.

One would imagine that Durant would strenuously rebel against this feminism in ancient Athens, but no. In the final section of the chapter, devoted to Durant’s criticism of the philosopher, he wrote instead:

What Plato lacks above all, perhaps, is the Heracleitean sense of flux and change; he is too anxious to have the moving picture of this world become a fixed and still tableau…

Essentially he is right—is he not?—what this world needs is to be ruled by its wisest men. It is our business to adapt his thought to our own times and limitations. Today we must take democracy for granted: we cannot limit the suffrage as Plato proposed…

…and that would be such equality of educational opportunity as would open to all men and women, irrespective of the means of their parents, the road to university training and political advancement.

Will Durant, who wrote this book in the 1920s, was nothing but a normie. And compared with us, white nationalists are normies too: as they have not figured out that, in addition to Jewry, they have enemies in the very fabric of history, which is why Plato proposed a static state.

A dynamic society is not recommended because, as we have said elsewhere, the human being is not ready for Prometheus’ fire. Since the Industrial Revolution whites have done nothing but commit ethnic suicide for the simple fact that they are still children playing with matches who burn their own house. That is why, at the end of my ¿Me Ayudarás?, I recommend a static society as Arthur Clarke described it in Against the Fall of Night when writing about Lys, a novella later expanded into The City and the Stars: the utopia that I imagine with the paintings of Le Lorraine.

A dynamic society is not recommended because, as we have said elsewhere, the human being is not ready for Prometheus’ fire. Since the Industrial Revolution whites have done nothing but commit ethnic suicide for the simple fact that they are still children playing with matches who burn their own house. That is why, at the end of my ¿Me Ayudarás?, I recommend a static society as Arthur Clarke described it in Against the Fall of Night when writing about Lys, a novella later expanded into The City and the Stars: the utopia that I imagine with the paintings of Le Lorraine.