Or:

A key to understanding the ethnosuicidal United States

I had said in the previous post that I would not read beyond page 500. But a friend on Facebook suggested that I read what Heisman says about the Norman Conquest and I have found oil. I wonder if those white nationalist scholars in the history of Britain and the United States know this thesis? Although Heisman was a Jew, in good hands his thesis could be a vital piece to put together the puzzle of the whys of white suicide, which leads the United States of America. Heisman wrote:

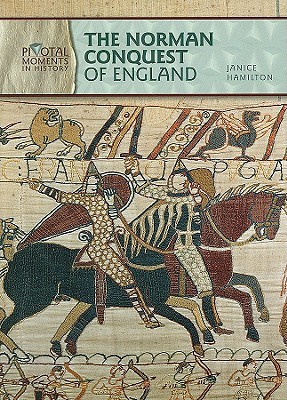

Remarkably, the Anglo-Saxons and Germans are very closely related in their cultural-ethnic origins. Yet during the Nazi period, the Germans continued a cultural-political path that lead to an idealization of the Jews as their greatest mortal enemies, the destruction of Western cultural values inherited from Christianity, and the systematic genocide of the alleged propagators of those values. The Americans ventured towards the total opposite historical trajectory becoming perhaps the most Christian nation of the developed world, the most culturally compatible nation with the Jews, and the greatest ally of the state of Israel. At the root of this historical divergence between the Anglo-Saxons and the Germans lay the Norman Conquest. […]

Remarkably, the Anglo-Saxons and Germans are very closely related in their cultural-ethnic origins. Yet during the Nazi period, the Germans continued a cultural-political path that lead to an idealization of the Jews as their greatest mortal enemies, the destruction of Western cultural values inherited from Christianity, and the systematic genocide of the alleged propagators of those values. The Americans ventured towards the total opposite historical trajectory becoming perhaps the most Christian nation of the developed world, the most culturally compatible nation with the Jews, and the greatest ally of the state of Israel. At the root of this historical divergence between the Anglo-Saxons and the Germans lay the Norman Conquest. […]

An essential inheritance of America’s Anglo-Protestant values is an inclination to forget ethnic origins, national rivalries, and presumptions of hereditary status that were characteristic of the Old World. The Anglo-Saxons planted the model of this morality of turning a blind eye to national origins for all other Americans to follow and this implicated the erasure of everyone else’s ethnic origins as well. The freedom to forget the past appears to be the obverse side of America’s traditionally optimistic vision of the future. But why is this past problematic? Why were hereditary origins an issue in the first place?

The “race problem” should not matter in America, yet somehow it is the most American issue, the most relevant innovation of the entire American experiment. The old answers, moreover, that attempted to account for the entire “race” issue simply do not add up. There is a lack of coherent answer to the question of why race matters.

American historian Gordon Wood observed that

the white American colonists were not an oppressed people; they had no crushing imperial chains to throw off. In fact, the colonists knew they were freer, more equal, more prosperous, and less burdened with cumbersome feudal and monarchical restraints than any other part of mankind in the eighteenth century.

What exactly were the colonists rebelling against, then? What was this world-historical commotion called “revolution” really about?

Conquering the Conquest, or, Enlightened Saxon-centrism

The unanswered questions about race and revolution can be concentrated into a single historical question: When did the Anglo-Saxon nation stop being conquered by the Normans? For the sake of empirical accuracy, let us refuse to indulge in vague abstractions or undemonstrated traditional assumptions of assimilation. If we demand a specific, empirical date or period that marks a distinct end to the Conquest, what can the study of history offer?

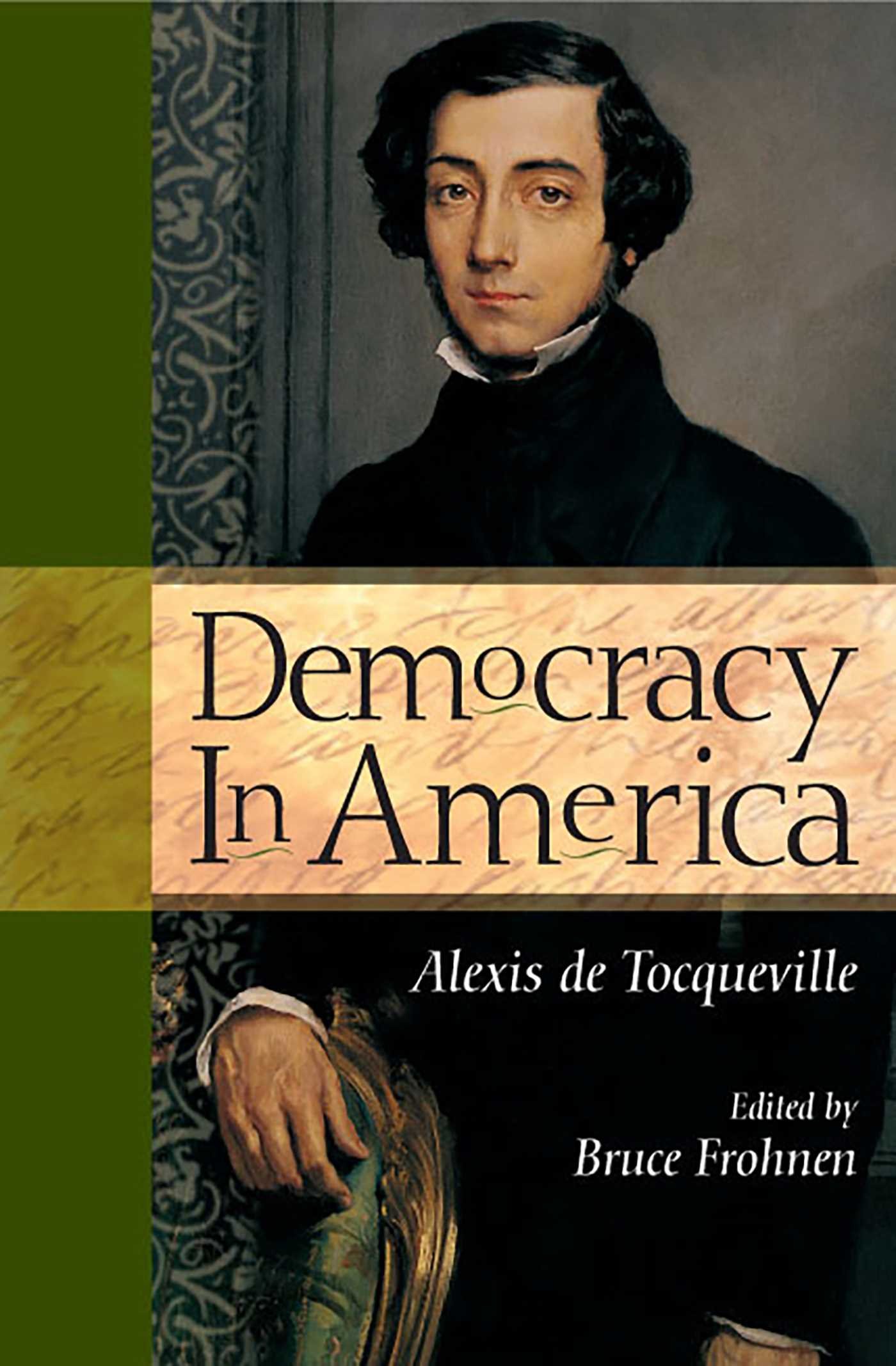

Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville, a descendant of an old aristocratic family from Normandy, wrote in his famous treatise on American democracy, “[g]eneral ideas do not attest to the strength of human intelligence, but rather to its insufficiency.” The holy abstraction of “freedom” has effectually pulled wool over the eyes of those who have mindlessly submitted to the authority of the metaphysics of freedom. Freedom, in this way, seems to grant freedom from rational reflection upon the authority of “freedom.” Instead of being misled by fuzzy, mystical, metaphysical abstractions such as “freedom”, let us ask, specifically and empirically, freedom from what? In its distinctive historical context, what exactly was it about the British political order that radicals such as Thomas Paine sought freedom from?

The very title of Paine’s book, The Rights of Man, might suggest a tendency to abstract or grossly generalize his particular anathema to “hereditary government” in England and France in universal terms. Yet this appearance does not fully stand up to scrutiny. In the case of England, he inquired specifically and empirically into the identity of its hereditary government and followed its very own hereditary logic back to its hereditary origins to discover:

that origin is the Norman Conquest. They are evidently of the vassalage class of manners, and emphatically mark the prostrate distance that exists in no other condition of men than between the conqueror and the conquered.

This means that the “prostrate distance” between the conqueror “class” and the conquered “class” was also a hereditary distance. This kinship discontinuity between rulers and ruled suggests possible grounds for ethnic hostility between the descendants of the aristocracy and the majority population.

In The English and the Normans: Ethnic Hostility, Assimilation, and Identity, historian Hugh Thomas documented the ethnic hostility that existed between the native English and Normans following the Conquest. Justifying a common tendency to conflate ‘Anglo-Saxon’ with ‘English’, he maintained that English identity ultimately triumphed over both Norman identity and ethnic hostility. His thesis implies a kind of democratic cultural revolution and a belief in Anglo-Saxon conquest through cultural identity imperialism. If Thomas was right, then we should really date the first “modern” step towards democratic cultural revolution around the beginning of the thirteenth century. But was the Conquest really conquered so easily?

If the Norman Conquest, Norman identity, and ethnic hostility were conquered so easily, then how does Hugh Thomas explain these words of Thomas Paine in The Rights of Man?

The hatred which the Norman invasion and tyranny begat, must have been deeply rooted in the nation, to have outlived the contrivance to obliterate it. Though not a courtier will talk of the curfew-bell, not a village in England has forgotten it.

This is a direct refutation of the Hugh Thomas’s thesis, in The English and the Normans, that ethnic hostility ended by the beginning of the thirteenth century. Paine provided a powerful refutation, not simply as an observer, but as a highly influential embodiment of ethnic hostility against the Norman conquerors and their legacy. So who is right, Hugh Thomas or Thomas Paine?

The historian noted, “[l]ong-standing ethnic hostility would have completely altered the course of English political, social, and cultural history.” This unverified assertion that ethnic hostility did not continue significantly past the period covered by his study (1066-c.1220) was also contradicted by Michael Wood’s recollection of his childhood encounter with Montgomery in the 1960s:

Monty, of course, still bore his name and still carried his flag. And that explained his take on the Conquest. For though he was as English as I was, he saw himself as a Norman—and that’s what counts when it comes to matters of identity… as far as I was concerned, Monty would always be a Norman.

Still, in the twentieth century, the old ethnic identities mattered.

Did “Englishness” mean more than a quirk of geography, and more than “class”, to a hereditary Norman dominion eventually engulfed Ireland and Scotland as well? The label of Englishness certainly triumphed and the very core of the English language re-emerged. Yet England ultimately became something different, neither Norman nor English, but neither and both. Even if we ignore actual hereditary descent, the famous, and distinctively English “class system” dates from the Conquest and can itself be considered a long-term cultural triumph of Norman identity.

Genealogist L. G. Pine attested to the fact that the prestige of a Norman pedigree, associated with the identity of the “best people” or upper class, triumphed to the extent that many ambitious native English wanted to be Normans throughout post-Conquest English history. Ultimately, it was not so much that Normans became English so much that the English became British. The permanent occupation of the conqueror “class” formed the hereditary basis of the “British” Empire. While Thomas is fundamentally wrong, it is fortunate that he has clarified the issue by rightly raising the point that the reality of early post-Conquest ethnic hostility should wake people out of the complacent assumption that Normans and English should ultimately merge into one people.

Cultural assimilation is one thing; genetic assimilation, however, is quite another. Here the deficiency of historical studies that fail to account for biological factors and a general evolutionary perspective becomes most apparent. While Thomas’s scholarship offers many contributions to the debate, especially his balanced judgment on many topics, conclusions about the ultimate effects of the Conquest will remain fundamentally unbalanced if genetic factors are left out of the final equations.

Thomas writes history as if Charles Darwin never lived. Even if the Normans had completely assimilated culturally yet maintained a hereditary monopoly of leading positions within the country, that cannot be called full assimilation. The notion of special political-hereditary rights and privileges passed on from generation to generation that the American revolutionaries fought against in theory are the exact opposite of genetic assimilation.

Thomas’s thesis makes sense only if it can be demonstrated that the Anglo-Saxons are an ethnicity indifferent as to whether their government is or is not representative of “the people.” Thomas’s thesis could be saved only if the evidence verified that Anglo-Saxons are an ethnicity with no sense of the value of liberty, their fawning natural servility allowing them to live together with their new Norman aristocracy happily ever after. In summary, the real question of assimilation is whether the Anglo-Saxons assimilated to the notion that the Normans had a right to conquer them.

As L. G. Pine wrote, “The historian whose unthinking conscience allows them to justify the Norman Conquest, could as easily justify the Nazi subjugation of Europe.” Thomas’s perilous, conciliatory suppression of any negative attitudes towards Normans that could be construed as ethnic hostility led him to acquiesce in a neutral or sometimes even positive attitude of appeasement towards those exemplary Normanitas virtues expressed in ruthless military domination, genocide, and the crushing of all native ethnic resistance (a.k.a. conquest; the antithesis of the rights of man; the negation of the every principle that the most egalitarian of the American founders sought to bring to light in opposition to the founding of the British Empire in 1066).

Michael Mann’s The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing proposed two versions of “We, the people.” He proposed that the liberal version, exemplified by American Constitutionalism, is characterized by individual rights, class, and special interest groups. In the organic version of democracy ethnicity rivals other forms of interest and identity and in some circumstances can express itself in ethnic cleansing. This is the “dark side of democracy.”

In Central and Eastern Europe after the fall of the Soviet Union, Mann observed, “democratization struggles increasingly pitted a local ethnicity against a foreign imperial ruler.” The demos was confused with the ethnos. Was America any different? If the Normans conquerors achieved some degree of success in perpetuating their hereditary government over the centuries, and the original ethnic conflict that Thomas documented was not perpetuated with it, then how does one explain that? What would make the impetus of organic and liberal democracy so different from one another?

For the sake of argument, let us entertain this peculiar idea of hereditary separatism, just as John Locke does in his Second Treatise of Government (and try in earnest to assume this has nothing to do whatsoever with the Norman Conquest):

But supposing, which seldom happens, that the conquerors and conquered never incorporate into one people, under the same laws and freedom; let us see next what power a lawful conqueror has over the subdued: and that I say is purely despotical… the government of a conqueror, imposed by force on the subdued… has no obligation on them.

The Declaration of Independence proclaims, “to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” This assertion implies that the Norman Conquest was illegitimate. The Norman takeover was achieved despite the lack of consent of the governed. That government was instituted with strategic violence against any significant resistance from the governed. From the view of its author, Thomas Jefferson, the Norman Conquest was the institution of an unjust power against the rights of the people. It is thus not a coincidence that the hereditary “English” political tradition was founded in utter violation of the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

In The Rights of Man, Paine explained, “by the Conquest all the rights of the people or the nation were absorbed into the hands of the Conqueror, who added the title of King to that of Conqueror.” Paine posited a remarkable ambiguity between the “rights of the people” and “the nation.” King was equated with Conqueror. In 1066 there existed a right of conquest, but no “rights of the people.” The modern invention of the latter justified, at long last, the reclamation of Anglo-Saxon “rights” from the “hands of the Conqueror.”

The Declaration of Independence further asserts, “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.” America provided an opportunity to do just that.

Taking full advantage of this opportunity meant that America would truly be different from the old world. As The Rights of Man explained, “In England, the person who exercises this prerogative [as king] is often a foreigner; always half a foreigner, and always married to a foreigner. He is never in full natural or political connection with the country.” A lack of “natural” connection between the political elite and the people was significant for Paine. The contrast with America was clear: “The presidency of America… is the only office from which a foreigner is excluded; and in England, it is the only one to which he is admitted.” The new world would be different.

America, for Paine, was the place where foreigners were excluded from that high office. Democracy meant that “commoners” could finally be admitted. Revolution had turned the old order upside down: the rule of the people meant the triumph of Anglo-Saxon ethnocentrism over the legacy of the Norman-centric aristocracy.

It is unfortunate for believers in the distinct superiority of the liberal form of democracy that the organic and liberal varieties are more equal than they think. Faith in the categorical distinction between the liberal and organic expressions of democracy is only a display of naiveté towards the cunning of ethnocentrism. Democratic Saxon-centrism has prevented an appreciation of the ethnic diversity at the very heart of the American founding.

Are the Anglo-Saxon ethnically superior to ethnocentrism and thus superior to all other peoples on Earth in this respect or has something been overlooked? Is it true that Anglo-Saxons are always superior and never inferior to the power and influence of the Norman Conquest or is it at least possible that this unspoken assumption might have something to do with Anglo-Saxon ethnocentrism? It is as if a conquest of the Conquest has been attempted through an enlightened ethnic cleansing of the Norman impact on world history. The Norman conquerors of history, however, were not conquered so easily.

The Peculiar Revolution

For the title of original, permanent English colony in the New World, the Pilgrims of the Mayflower take second place. It was the English settlers of Jamestown, Virginia, who were the first permanent English colonists, thirteen years before the Mayflower. Jamestown was birthplace of the United States, and, it just so happens, the birthplace of American slavery of Africans. In 1619, a year before the landing of the Mayflower, the first black slaves were brought to Virginia.

America was born a land of slavery.

In the Old World, it had been “the Norman” who so often represented tyranny, aristocracy, and inequality. But surely things must have been different in America. In the land of freedom, democracy, and equality, perhaps only Southern slavery posed a truly fundamental challenge to these modern values.

The question nonetheless remains, who were these Southern slave masters?

It is as if recent historians have confidently assumed that, in all of human history, there could not be a case where the issue of race was more irrelevant. Never in human history was the issue of race more irrelevant than in regard to the racial identity of the American South’s essential “master race.” This is a truly fantastic contradiction: the South apparently fought a war in the name of the primacy of race, yet the distinctive racial identity of the South primary ruling race is apparently a matter of total indifference.

Virtually every other people in history, from the Italians, to the Chinese, to the Mayans, to the Albanians, possessed some form of ethnic identity. The French, the Germans, and the Russians did not and do not simply consider themselves to be merely “white.” The original English settlers of the North, moreover, are considered, not simply white, but Anglo-Saxon. Why, then, was the South’s “master race” nearly alone in its absence of a distinctive ethnic identity? Is this state of affairs only a consummation of the Northern victory?

Of course, that blacks possessed a distinctive African ancestry is admissible, but the ancestry of the South’s ruling race is apparently inadmissible. This must be a state of affairs almost more peculiar than slavery itself. Everyone else across the world is permitted a distinctive ethnic or racial identity except the great Southern slave masters. For some peculiar reason, the original Southern slave masters are not allowed to have a distinct ethnic or racial identity. This means that the only people in American history who apparently have no distinct ethnic or racial origins beyond being white are precisely the same people who thought other people could and should be enslaved on the basis of their ethnic or racial origins.

These aristocratic planters must have been the most raceless, bloodless, deracinated, rootless, cosmopolitan universalists ever known to history. We must conclude that of all white people, these aristocrats must have valued heredity or genealogy the very least. The Virginia planters were most peculiar, not for being owners of black slaves, but for being the least ethnically self-conscious white people in world history. Is this an accurate reflection of reality?

This is really one of the great, peculiar paradoxes of world history: the elite Southern planters, one of the most extreme, unapologetic, and explicitly racist groups in history, are precisely those who may have the most obscure racial identity in history. Their claim to fame has been tied to identifying blacks as a race of natural slaves and in identifying themselves as race of natural masters—a “master race” without a racial identity. Perhaps the time has come to recognize that they have also merited a claim to fame simply for the obscurity of their racial identity.

Who were they?

The Englishmen who first settled the North identified themselves as Anglo-Saxons. But what about the “First Families of Virginia”? Virginia’s Tidewater elite largely originated from the geographic entity of England. But did these racists consider themselves specifically Anglo-Saxon? This question must be posed as carefully as possible: did they or did they not specifically identify themselves as members of the Anglo-Saxon race?

Who were these American slave masters?

In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that the North possessed “the qualities and defects that characterize the middle class”, while the South “has the tastes, prejudices, weaknesses, and greatness of all aristocracies.” There could probably be no greater confirmation that South possessed a genuine aristocracy in the traditional sense. Yet this prescient antebellum observation begs the question: how did young America acquire an old aristocracy?

It is as if, in America, of all places, no explanation is required for this profound cultural difference between North and South. America was supposedly a country defined by “the qualities and defects that characterize the middle class.” But the idea of a slave race assumes the existence of a master race, not a bourgeois or middle-class race. The Union was not threatened by the leadership of poor Southern whites; it was threatened by the leadership of a subgroup of whites with an aristocratic philosophy that mastered the entire cultural order of the South.

If the Civil War was fought against slavery, and to fight slavery was to fight the slave-masters, then the Civil War was fought against the slave-masters. Since the slaves were not guilty of enslaving themselves, the argument that the Civil War was about slavery is practically identical to the argument that the Civil War was about the slave-masters. No matter which way one looks at it, all roads of inquiry into slavery leads to an inquiry into these peculiar Southern slave-masters.

Who were they?

“These slaves”, said Abraham Lincoln, “constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.” Did Lincoln state here that slavery was the cause of the war? No, Lincoln stated that slaves, as property, constituted an interest, and this interest was, somehow, the cause of war. The question then becomes, whose interest did these slaves serve?

To speak of aristocracy is to speak, by definition, of a minority of the population. The original aristocratic settlers of Virginia were called Cavaliers. “[T]he legend of the Virginia cavalier was no mere romantic myth”, concluded David Hackett Fischer in Albion’s Seed. “In all of its major parts, it rested upon a solid foundation of historical fact.”

But who were the Cavaliers?

One year before the outbreak of the American Civil War, in June of 1860, the Southern Literary Messenger declared:

the Southern people come of that race recognized as cavaliers… directly descended from the Norman barons of William the Conqueror, a race distinguished in its early history for its warlike and fearless character, a race in all times since renowned for its gallantry, chivalry, honor, gentleness and intellect.

Normans and Saxons: Southern Race Mythology and the Intellectual History of the American Civil War documented the thesis of Norman/Saxon conflict from a literary perspective. Its author, Ritchie Devon Watson, Jr., interpreted this thesis of Norman-Cavalier identity as “race mythology”, just as historian James McPherson has called this peculiar notion the “central myth of southern ethnic nationalism.” Yet how can this thesis be dismissed as myth without a thorough, scientific, genealogical investigation into the matter? Is it a myth, rather, that the Norman Conquest, the most pivotal event in English history, had no affect whatsoever on America? Is it true that representatives of virtually every ethnicity and race have come to America—with one peculiar Norman exception? Were the descendents of the Norman-Viking conquerors of England the only people in the world who were not enterprising or adventurous enough to try their fortunes in a new land?

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union,” Lincoln explained, “and is not either to save or destroy slavery.” Yet it has become commonplace to disagree with Lincoln and to propagate the myth that the Civil War was first and foremost about the slavery of black people. The repeated claim that the Civil War was about slavery can be deceptive because it serves as a means of avoiding focus upon the slave-masters, which further avoids facing the centrality of the identity of the Norman-Cavaliers. The American Civil War was fought primarily, not over black slavery, but over Norman mastery.

There is a sense, however, in which the Civil War was provoked by the slavery of a race of people. Norman-American George Fitzhugh, the South’s most extreme and comprehensive pro-slavery theorist, clarified the relationship between race, slavery, and the Civil War amidst that violent clash of two Americas:

It is a gross mistake to suppose that ‘abolition’ is the cause of dissolution between the north and south. The Cavaliers, Jacobites, and Huguenots of the south naturally hate, condemn, and despise the Puritans who settled the north. The former are master races, the latter a slave race, the descendants of the Saxon serfs.

This is a key piece of the racial puzzle of America. Fitzhugh implied that the North sided with a black slave race because the Anglo-Saxons themselves are a slave race. Fitzhugh depicted Anglo-Saxons as the niggers of post-Conquest England.

With these words, Fitzhugh verified that the Norman Conquest, in its origins, was a form of slavery of the Anglo-Saxon race. The foundational irreconcilability between North and South is incomprehensible without recognizing that North’s peculiar obsession with “freedom” evolved precisely from the fierce denial that they or their ancestors were, in fact, a Saxon “slave race” born to serve a Norman “master race.”

“True,” Horace Greeley admitted in an issue of his New York Daily Tribune in 1854, “we believe the tendency of the slaveholding system is to make those trained under and mentally conforming to it, overbearing, imperious, and regardless of the rights of others.” Would he have believed, too, that the tendency of the Saxon-holding system in England after 1066 was to make those trained under and mentally conforming to it, overbearing, imperious, and regardless of the rights of others? Could there be any connection between these two very peculiar tendencies?

Could revulsion against the very notion of a slavish Saxon-holding system be the root and source of the inordinately strong Anglo-Saxon tendency toward freedom? The key to understanding the modern fame of the Anglo-Saxons as a free race is to understand the medieval fame of the Anglo-Saxons as a conquered and enslaved race. The Norman-Cavaliers’ belief in the rectitude of slavery was a direct descendant of belief in the rectitude of the peculiar institution of the right of conquest.

Yet, as Fitzhugh made clear, he and other Cavaliers were not the only whites of the South, even if they were as decisive in forming the culture of South as the Anglo-Saxons were in forming the culture of the North. The Jacobites refer to the Scotch-Irish who became the majority of the Southern white population. A smaller population of French Huguenots followed the original Cavaliers and concentrated in South Carolina.

According to the late American political scientist Samuel Huntington, “American identity as a multiethnic society dates from, and in some measure, was a product of World War II.” Huntington believed that America has a Puritan essence. He implied that American identity is rooted in a single ethnic identity and that ethnic identity is Puritan and Anglo-Saxon. If this is true, then it goes without saying that ultimate patriarch among the “founding fathers”, George Washington, must have been a pureblooded Anglo-Saxon. Is this genealogically accurate?

According to one source, the very first Washington in England was originally named William fitzPatric (Norman French for son of Patric). He changed his name to William de Wessyngton when he adopted the name of the parish in which he lived circa 1180 A.D. Another source, the late English specialist in Norman genealogy L. G. Pine, related that George Washington and his family “has plenty of Norman ancestry.” He confirmed that this family was on record as owners of Washington Manor in Durhamshire in the twelfth century and of knightly rank. Since George Washington was the possessor of “a carefully traced decent from Edward I,” this implies that the first president of the United States was also a descendant of William the Conqueror. None other than the twenty-eighth president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, affirmed in his biography of Washington that his Cavalier ancestors “hated the Puritans” and that the first Washingtons in Virginia were born of a “stock whose loyalty was as old as the Conquest… They came of a Norman family.”

George Washington was a Norman-American and a classic representative of the aristocratic, slave-owning, Cavalier culture of Virginia. Unfortunately for Mr. Washington, Samuel Huntington has no room for the kind of diversity represented by America’s first president and his Puritan hating, Cavalier ancestors. Everyone must conform to the Anglo-Saxon, Puritan cultural model if they want to be counted as real Americans—even George Washington. Wasn’t that what the Civil War was about?

How is it even conceivable that Norman conquerors who developed into Southern slave masters could also have played a decisive role in the architecture of American liberty? Huntington, so keen to stress the English roots of American liberty, neglected to point out that Magna Carta was a product of Norman aristocratic civilization. It was the Normans who first invented the formal tradition of constitutional liberty that eventually conquered the world.

So while Washington was an heir to Norman aristocratic tradition, Magna Carta was a part of that tradition. Southern resistance to King George III in 1776 could trace its struggle for liberty to the resistance of Norman barons to King John in 1215 (and this also preserved their special privileges or “liberties” against the tide of assimilation with Anglo-Saxons). It was only in the seventeenth century that Anglo-Saxons exploited and selectively reinterpreted Magna Carta for their own purposes.

The ultimate foil of Hugh M. Thomas’s thesis that ethnic hostility between Normans and Anglo-Saxon went extinct by about 1220 is to be found in the endurance and persistence of Samuel Huntington’s question: Who are we? The “universalism” of the American founding actually emerged out of the attempt to preserve a rather peculiar form of multiculturalism that balanced the democracy-leaning North against an aristocracy-leaning, slaving owning South. The American Civil War resulted in the Northern conquest of the multicultural America that formed the character of the American founding. The Anglo-Saxon conquest of 1865 was the real founding of Samuel Huntington’s presumption of a single Puritan-based American culture.

What Hugh Thomas actually did was to dig up the root of the Anglo-Saxon cultural identity imperialism that late twentieth century multiculturalism began to expose. Thomas’s conclusion that the Anglo-Saxons culturally conquered the Normans in thirteenth century was made seemingly plausible only by nineteenth century conquests of the Normans. Thomas only uncovered the origin of this Anglo-Saxon way of cultural conquest through a struggle against the multicultural England of medieval times.

Multiculturalists who have promoted the contributions of women and minorities at the expense of the usual dead white males of history are following directly in the footsteps of Anglo-Saxon historians who downplayed the Norman impact on their history. The underdog biases of multiculturalism is not an aberration, but only a continuation of the majoritarian bias of democracy itself against a fair assessment of the contributions of Norman aristocracy to world history. William the Conqueror is the ultimate dead white European male in the history of the English-speaking world.

Hugh Thomas’s unspoken assumption is that Anglo-Saxons culturally conquered the Norman Conquest. They, the Anglo-Saxons, were ultimately history’s great conquerors. But is this true? Let this point resound around the entire world with utmost clarity: the issue here is who conquered whom? Did the Normans become victims of conquest by the Anglo-Saxons in modern times through characteristically modern methods?

Is it all possible that Anglo-Saxons might possibly be biased on the subject of the people who once defeated, conquered, and subjugated them? Most humans have submitted to the yoke of a “modern” Anglo-Saxon-leaning interpretation of long-term effects of the Norman Conquest. The repression of the impact of 1066 upon modern times has stifled a rational, evolutionary understanding of liberal democracy in the English-speaking world. The time has come for America and the rest of the English-speaking world to overcome this ancient bloodfeud and reclaim its Norman heritage, a heritage to goes to the very heart of the American founding.

In modern times, the Anglo-Saxon culturally conquered the Normans by Saxoning away their multicultural difference into presumptions of Anglo-Saxon “universalism.” To call America “Anglo-Saxon” is thus tantamount to ethnically cleansing George Washington of his Norman or Cavalier ancestral identity. Was George Washington the victim of a cultural form of ethnic cleansing by the Anglo-Saxon people?

[pages 654-675]

Alexis accepted a government mission to travel to the United States to study its prison system; his stay there lasted nine months. The fruit of this trip was a work on American prisons but his stay served him to deepen his analysis of the American political and social systems, which he described in his work Democracy in America (1835-1840).

Alexis accepted a government mission to travel to the United States to study its prison system; his stay there lasted nine months. The fruit of this trip was a work on American prisons but his stay served him to deepen his analysis of the American political and social systems, which he described in his work Democracy in America (1835-1840).