Excerpted from

March of the Titans:

A History of the White Race

by Arthur Kemp:

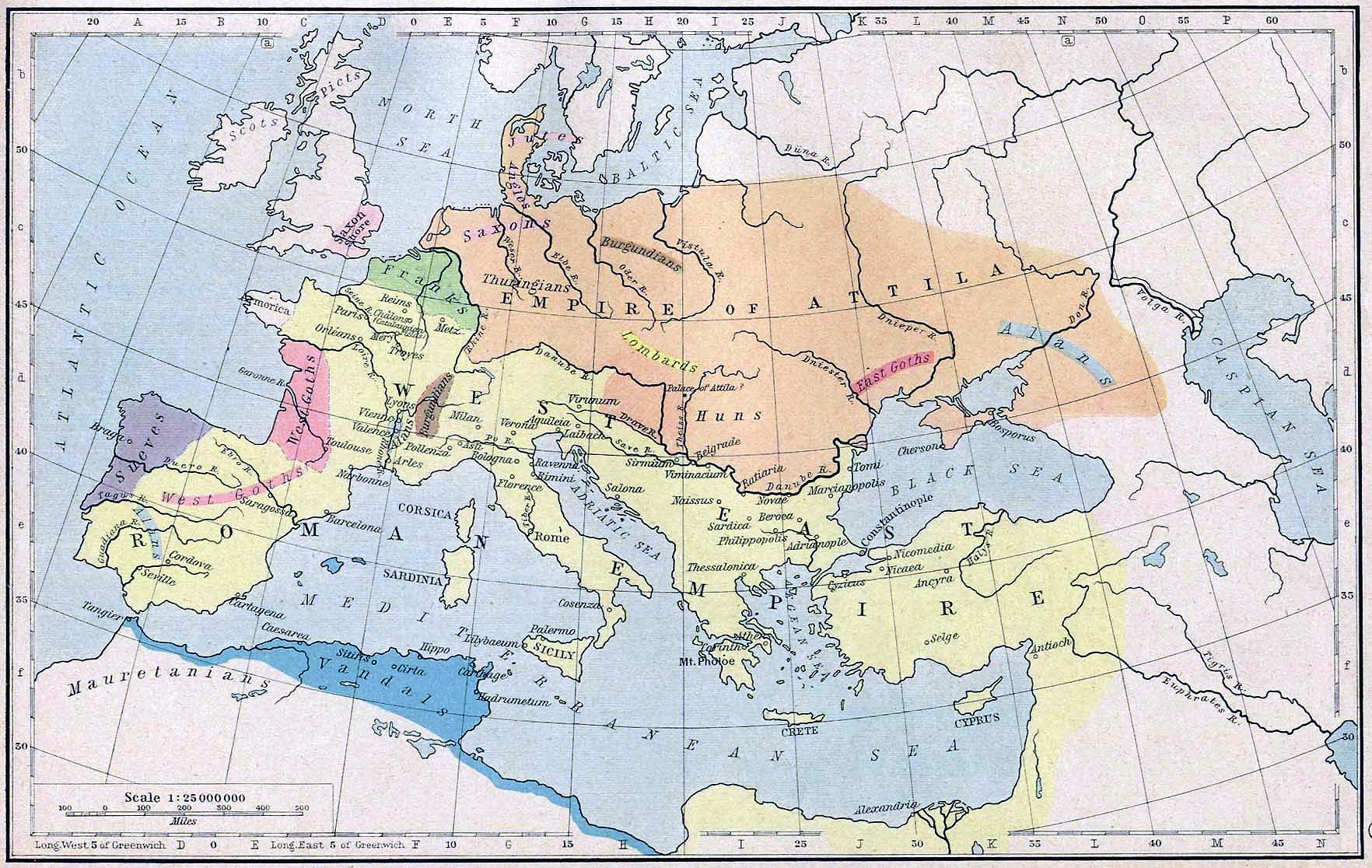

The first great race war – Attila the Hun

The Goths and their racial cousins kept up a continuous localized war with the Romans for many years, and would have doubtless continued to do so for even longer had a new powerful racial foe not emerged which threatened to destroy the Goths, Germans, Romans and indeed all of Europe.

Alans – The first victims

Physically described by Romans as being “short, brown skinned and slant eyed” the Huns emerged from Central Asia and burst upon the easternmost Whites, a tribe called the Alans, in 372 AD. The Alans, a Nordic tribe still living in the ancestral homeland between the Black and Caspian Seas, were crushed by the Huns who had developed cavalry fighting to a fine skill. Remnants of the Alans fled south and west—to this day there are traces of this last Nordic tribe to be found amongst the present day inhabitants of the region.

The Alans who fled westwards sought refuge with the Ostrogoths, bringing with them the first news of the new Asiatic terror.

Ostrogoths fall before Hun invasion

If the Ostrogoths wondered what had befallen the Alans, they did not have to wait long to find out. Very soon the Huns swept even further west and invaded the Ostrogothic lands (in modern day western Russia) and defeated them as well.

The Ostrogothic king, Hermanric, committed suicide when the scale of the invasion became apparent, and his successor, Vitimer, was killed while trying to hold back the Huns. The Ostrogothic kingdom in western Russia disintegrated, and its survivors streamed further westwards, into the lands of the Visigoths and Slavs.

Above is a depiction of a scene which befell hundreds of thousands of Whites. A raiding non-White party attacks a Roman villa, killing the males and carrying off the White women for sexual slavery.

Athanaric, king of the Visigoths, engaged the Huns at the Dniester River in modern day Bulgaria, but the Huns defeated the Visigothic army as well. After this defeat, the Visigoths were forced to fall back and beg the Romans for permission to settle inside Roman territory.

This appeal was made all the more remarkable when it is borne in mind that the Romans and Visigoths had been at virtual constant war for near enough to two centuries. So when the Romans finally gave permission to the Visigoths to move into Roman territory, it was at a terrible price—the Visigoths had to surrender all their weapons and hand over large numbers of their women and children as hostages.

Crossing the Danube in 376 AD and settling in modern day Bulgaria, the Visigoths managed to gain a temporary reprieve from the ravages of the Huns. The conditions under which the Romans forced them to stay were such that it was not long before Visigothic resentment boiled over into open rebellion.

The Visigoths secretly re-armed themselves and launched a campaign against the Roman strongholds of Thrace and Macedonia in northern Greece. Finally, in the battle of Hadrianople (378 AD) in modern day Greece, a Visigothic army defeated a Roman army under the personal command of the Emperor Valens—who had been the one to impose the harsh conditions of refuge upon the Visigoths. Valens himself was killed in this battle.

The defeat was all the more ironic as a large number of the Roman army’s soldiers were in fact Gothic mercenaries. The Eastern Roman Empire then accepted the presence of the Visigoths in central Europe, and lifted many of the restrictions placed upon them by Valens.

While the Goths and the Romans were grappling with one another, the former Visigothic lands were being seized by the Huns.

By the time of the Battle of Hadrianople, the Huns had occupied most of Dacia, the land originally seized by the Visigoths from Romans (and which corresponds to the present day country of Rumania).

Europe almost entirely invaded

At this stage the racial balance of Europe could have swung decisively in favor of the Asiatic Mongolians—all the original White ancestral homelands had been either destroyed or occupied by the Huns.

In addition to this, the Huns also physically occupied large parts of western Russia and portions of central and eastern Europe, including entire portions of modern central Germany, Hungary and Rumania, turning them overnight into mini Asiatic states.

Not content with these conquests, the Asiatic Huns began pushing further westwards, causing entire nations to be moved and destroying virtually everything in their path.

In this way the remnants of the Alans, and many other minor Nordic tribes were forced westwards, in turn displacing other already settled tribes. It was this displacement which led to further migrations of assorted Germanic tribes into Spain and even as far as North Africa.

By 432 AD, during the reign of Roman Emperor Theodosius I, the Huns had increased their power base and stranglehold on eastern and parts of central Europe to the point where they actually collected a large annual tribute from Rome. (By this time Rome was totally dependent on “barbarian” or German and Gaulish mercenaries for its defense—the mostly mixed race population of Rome had long since lost any social cohesiveness and ability to provide recruits for the army).

Attila the Hun – brutal leader

In 433 AD, the Huns gained a new king, whose name would become a byword for the Asiatic terror—Attila.

The new Asiatic king established his headquarters at the village of Buda on the Danube River in 445 AD (Buda was later to combine with another village on the other side of the river, Pest, to become Budapest, the modern capital of Hungary).

By this time the Hunnish empire stretched from the Caspian Sea in the east right up to the North Sea. In all of the area the Huns carried out a vicious racial war of extermination against the Whites who militarily were too weak to resist. Countless White settlements were wiped out, with the women routinely being carried off into captivity.

In 452 AD, Attila began moving west again, with the intention of seizing France and finishing off all of Europe.

Hunnish blood enters eastern Europe

By this stage the Huns had started on a limited scale to physically integrate with sections of the peoples they had conquered. Traces of the Mongolian influence can still be seen amongst some peoples in eastern Europe (the so called “Slavic look” which in fact is not Slavic at all, but mixed Mongolian/Slavic.)

Possibly as a result of this limited integration process, the Huns managed to recruit some locals into their army, and units of various eastern European tribes found themselves in the Hunnish army which finally invaded France. They were dealt with extremely harshly by their distant racial cousins if captured. The vast majority of the Hunnish army were however Mongolian and under the ultimate leadership of the unquestionably militarily astute Attila.

The Huns stood poised to push through to the Atlantic Ocean—Europe stood on the very brink of extermination.

The Battle of Troyes – Whites unite to defeat the Asiatics

The threat of the Hunnish army finally forced the ever squabbling Romans and Visigoths into an united front. A Roman army, under the last of the Western Empire’s properly Roman generals, Aetius, joined up with a Visigoth army under their king, Theodoric I, and together they met the Hunnish army in central France near the present day city of Troyes in 451 AD.

In a day long battle, both sides inflicted heavy casualties on the other, with the Visigoth king, Theodoric, being killed in the fighting. By nightfall the combined White army had gained the upper hand over the Asians.

Attila was forced to retreat all the way across Europe as far as Hungary, exacting a terrible revenge in slaughter and looting from those White settlements unfortunate enough to be in his path of retreat.

Defeated in the west, Attila made one last attempt to destroy the Whites. In 452 the Asians invaded northern Italy and razed the city of Aqueila to the ground, massacring as many of the inhabitants as they could find (the survivors fled into the nearby marshes, there to later establish the city of Venice).

Suddenly in 453 AD, the sixty year-old Attila died—allegedly of a burst blood vessel incurred during his wedding night exertions following his marriage to a local German princess. (How much of that story is true is open to question: what is fact is that he took a blond German girl, named Hildico, as his wife, following an example set by many of his Mongolian warriors, whose genetic footprint can be seen on some faces in eastern Europe and Russia to this day.)

The Battle of Nedao – Germanics save the white race from extinction

Attila’s death was the signal for a revolt of the people subjugated by the Huns. In 454 AD, the Goths, Slavs and others in Europe who had managed to survive the nearly 70 years of cruel Asiatic rule, rose up and at the battle of Nedao in that year, defeated the Huns in a straight fight between a Mongolian and a Germanic army. The victory was total and the Huns were finally destroyed.

The battle of Nedao became one of the most significant battles in White history, for without it Europe would most likely have been completely overrun by Asiatics before 500 AD.

The battle of Nedao became one of the most significant battles in White history, for without it Europe would most likely have been completely overrun by Asiatics before 500 AD.

The Germans, as victors over the Huns, became famous amongst their Indo-European racial cousins, with the Icelandic word for German to this day translating literally as “peoples’ defender”.

Suffering total defeat at the hands of the Germans, the vast majority of the surviving Asiatic Huns then fled back into the Far East, to the Sea of Azov in Russia—fearing the retribution by the Whites that would follow (a fear which was fully justified, as the enraged and victorious Whites mercilessly put to death any bands of Hun stragglers they found).

The Hunnish legacy

However, the Huns left two significant things behind them—firstly they gave their name to the area which had functioned as their headquarters during their racial war, Hungary.

Secondly, some admixture of Mongolian genes occurred amongst the Slavic tribes which had been under the Asiatic Hunnish occupation for nearly 80 years. This was however by no means complete and only ultimately affected a small, but significant, number of the Indo-European Slavs.

The Slavs then expanded eastward into the regions of Russia which had been overrun by the Huns on their way west. There they also mixed with scattered remnants of the partly Hunnish, partly Slavic peoples the Huns had left behind.

All these mixes contributed towards creating the distinctive Russian “Slavic look” visible to this day in a small percentage of the eastern European population in Russia and elsewhere.

The greatest effect of the Hunnish invasion of Europe was however the extinction of the source of the Indo-European tribes from their ancestral homeland between the Black and Caspian Seas. Never again would this territory produce another Indo-European Nordic tribe—the fountain of new Nordic tribes was forever extinguished, one of the most significant acts of racial genocide ever seen.

The second great race war – the Crusades

• By 700 AD, Islamic armies had occupied North Africa and had destroyed what remained of the Gothic Vandal state.

• As the Crusaders approached Antioch [during the siege of that city], the Muslim defenders under Turcoman Yagji-Shah started killing all the remaining Whites in the city, along with any non-White Christians who had the misfortune to be present… By nightfall of 3 June 1099, the city was in White hands—and every non-White who had foolishly remained behind in the city was dead.

• By the time they [the Crusaders] got to Constantinople however, the wonder on the European faces must have been apparent—they appeared to have as little in common with the Byzantine Empire as with the Muslims, not only racially, but even in language. The Byzantine Christians did not recognize the Pope, spoke Greek instead of Latin and had distinctly Middle Eastern art and architectural forms.

Unlike the Hebrews’ ethnic cleansing policies recounted in the Old Testament, in the Crusades westerners committed the same mistake of all white conquests throughout history, even after capturing Jerusalem. Kemp writes:

However, the Crusader states did not try to change the population make-up of the region by enforced migration or expulsion—nor did they even try to convert the natives. So it was that the first European colonies were created: ironically in the areas where once their now very distant racial cousins had once walked… The Crusaders’ failure to majority populate the areas they conquered with their own racial kind led to their disappearance in a very short while—so that now only their vast empty buildings stand as monuments to the spirit and heroism of the times.

In the 2011, printed edition of his book Kemp adds this phrase about the Crusades:

Never a majority, the white Christian soldiers were overrun, and within three hundred years almost all trace was vanished.

The third great race war – the Moors invade Europe

The invasion of Western Europe by a non-White Muslim army after 711 AD, very nearly extinguished modern White Europe—certainly the threat was no less serious than the Hunnish invasion which had earlier created so much chaos. While the Huns were Asiatics, the Moors were a mixed race invasion—part Arabic, part Black and part mixed race, always easily distinguishable from the Visigothic Whites of Spain.

To give a flavor of the content of this chapter I will add some subtitles to the images that Kemp chose for this specific chapter—omitting the images:

• Above: A dramatic painting—based on actual events—showing Moors celebrating the fall of a White Spanish town, with White females captured alive. For several years the Moors demanded—and received—a yearly tribute of young White girls for use in their harems after the great Moorish victory of 711. This yearly tribute continued until 791 AD when the Whites had recovered their strength enough to break the terms of a treaty with the non-Whites.

• Above: Captured White prisoners about to be decapitated by Saracens: note how the Spaniards are depicted with blond hair.

• Above: The non-White Moorish advance into Europe seemed unstoppable when in 732 AD they launched a massive invasion of present day France. The king of the leading White tribe in that country, Charles Martel of the Franks (who had their headquarters in present day Paris) mobilized a counter attack. A great race battle took place between the towns of Tours and Poitiers in central France in October 732 AD. The battle was one of the most momentous in the history of the White race. Defeat would have meant that all of Western Europe might have fallen under the sway of Islam, and the mixed races from the East would have poured into continental Europe. Accounts have it that 375,000 Moors were killed—the White army was utterly victorious over the non-White army and the Moorish invasion of Europe was halted in its tracks. Charles Martel earned his name—Martel means “hammer”—at this battle—he personally bludgeoned to death a large number of non-Whites with his favorite weapon, a mighty hammer.

The fourth great race war – Bulgars, Avars, Magyars and Khazars

The lands making up western and southern Russia, Asia Minor (Turkey) and the southeastern Balkans were to be the scene of some of the most dramatic racial conflicts between various tribes of Europeans on the one hand, and various Asiatic, Mongol, and mixed race Muslim armies on the other.

These wars started around 550 AD, a century after the crushing of the Mongolian Hunnish invasion of Europe. They only finally stopped with the defeat of new Asian invaders some 400 years later, with the defeat of an Asiatic alliance known as the Magyars, in Bavaria in 954 AD.

This massive struggle against Asian and Mongolian hordes can rightly be grouped into one heading, even though different players acted in the drama.

If these combined Asian invaders had not been turned back, then it would most certainly have given the non-White Moorish invasion in Spain, which took place in the same time span, a far better chance of success. The White race might have been exterminated between the Asians and the Moors—but it was not.

The fifth great race war – Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan’s first raid was into Russia in 1221, when his army smashed their way through several southern Russian principalities who were taken completely unawares by the yellow-skinned Mongolians.

Soon a huge part of southern Russia was under the sway of Genghis Khan—and not even the efforts of the Russian tribes to the north could dislodge him.

The invasion of southern Russian was in fact the only invasion of White held lands in which Genghis himself took part. He died suddenly in 1227, and the Mongolian armies paused for several years in southern Russia while a successor to Genghis was chosen from amongst the leading Mongolian chieftains.

In the interim the Mongols instituted a grim reign of terror over the White tribes they had subjugated. Whole settlements were slaughtered en masse, with lucky survivors barely escaping to the north and west, bringing tales of terror from the new Asiatic invaders.

One tactic for which the Mongols became famous was to sack a town, leave and then a few days later send a rearguard party back to the sacked town to see if any survivors had made their way back—any such unfortunates were put to death on the spot. In this way entire regions were quite literally stripped of all living souls.

Finally in 1236, the Mongol armies moved again, striking westwards in such numbers and ferocity that they reached deep into the Balkans, Hungary, northern Russia, Poland and central Germany.

Under the leadership of one Batu, a grandson of Genghis Khan, the Asiatics resumed their westward invasions in 1237, sacking the Russian city of Kiev in 1240, continuing westward into Poland, Bohemia, Hungary, and the Danube River valley.

Whites defeated at battle of Leignitz

An alliance of Germans, Poles and Teutons under the command of Duke Henry II of Silesia formed a united White army and desperately tried to stem the Asiatic advance. They met the Mongols in battle at Leignitz in what was then Poland in April 1241, but were badly defeated. Henry was beheaded by the Mongolians and for several days afterwards his impaled head was carried around on a spear at the head of the Mongol army until it rotted away.

The southern Indo-European tribes, the Slavs, then put together a new White army and launched an attack on the main body of the Mongol army in southern Europe. The battle, fought just north of Budapest, at the Sajo River in April 1241, saw the White armies defeated once again. The combined defeats inflicted upon the Russians, Germans and Slavs meant that all of Europe lay open to the Mongols.

In 1242, the Mongol hordes penetrated into the suburbs of Vienna itself—at that critical moment the non-White invasion ceased of its own accord.

In 1242, the Mongol hordes penetrated into the suburbs of Vienna itself—at that critical moment the non-White invasion ceased of its own accord.

It was a quirk of destiny which saved Europe and its peoples from complete extermination at the hands of the Mongols. In December 1241, the Asiatic army had just started on their final drive westwards, marching across the frozen Danube River, when a messenger arrived from their homeland in Mongolia—the successor to Genghis Khan had died. Then and there, the Mongol army turned around and withdrew back to the east. Leaderless, they were never to penetrate into central Europe again.

Even though the Mongols withdrew from central Europe, all of eastern and southern Russia remained under Mongol occupation, where Batu created what became known as the Khanate of the Golden Horde—the name originating from an annual tribute of riches extracted from the northern Russians, who only escaped occupation by formally acknowledging themselves as vassals by paying a yearly tribute to the Mongol rulers in the south.

The only eastern European state which was not humiliated in this way was Baltic Lithuania. As Mongol strength slowly declined, the Lithuanians expanded, eventually occupying an area stretching from the Baltic right to the Black Sea in the south. Lithuania in fact became the most powerful state in eastern Europe.

By the early 1300s, the Mongol Empire in the south had been wracked by internal divisions, with rival claimants to the Mongol throne launching a series of fratricidal wars amongst themselves. Seizing advantage of the confusion in the Asiatic ranks, the Grand Duke Dimitry of Moscow led an army against a huge Mongol force at Kukikovo, on the banks of the Don River, in 1330. Although great casualties were suffered by both sides, the White Russians won: the first major reverse suffered by the Mongols since their occupation of southern Russia.

Ivan the Great

The Mongols were then further weakened by renewed internal dissension, with a new Mongol warlord, Tamerlane, conquering much of the original Mongol Empire in Russia in 1395. After Tamerlane’s death, his empire was broken into four independent khanates: Astrakhan, Kazan, Crimea, and Sibir.

So divided, the Mongols were at last weakened to the point where the Muscovite principality, under the leadership of Ivan III, took the opportunity in 1480, to refuse to pay the annual tribute to the Horde.

Ivan, called The Great, who ruled from 1440 to 1505, then followed up the refusal to pay the tribute with a series of localized wars which expanded the borders of his kingdom—some were against other White principalities while some were against local Mongol chieftains. In this way a succession of slow moves south, combined with a process of assimilation, saw the last of the Mongol states vanish another century later, although the names they gave to these regions still persist.

The first major White reconquest of the southern parts of Russia only began in the mid 1500s, when bands of Russian peasants, known as Cossacks, fleeing the autocratic fiefdoms of northern Russia, started settling along the banks of the Don River basin.

The Cossacks engaged in a large clearing operation lasting many decades against the Mongols. By the mid-1600s the majority of Mongols had been cleared from central southern Russia—the remaining minority were for the greatest part absorbed into the new population.

The Mongol legacy

In central Europe, the Mongols were not physically present long enough to have a lasting genetic impact upon the local population, although unquestionably a small amount of Mongolian genes did enter the bloodstream of a tiny part of the population. This took place mainly through the wholesale rape of White women for which the Mongols were also famous. The major impact of the Mongol invasion upon southern and central Europe was that they physically killed huge numbers of Whites in their path, numbers which were lost forever.

In southern Russia however, the after-effects of three hundred years of Mongol rule left a clear genetic imprint upon many of the peoples in that region. Many of the peoples of regions such as Kazakhstan are of clear mixed racial origin. It is these people who are today often mistakenly called Slavs. Even though they were originally the easternmost Indo-European peoples and as such part of the Slavic tribes, their racial identify was completely submerged by the Mongol invasion and it would be genetically incorrect to classify them as Slavic.

The sixth great race war – the Ottoman Holocaust

The Ottoman Empire was the longest lasting non-White invasion of European soil ever. Lasting from the beginning of the 13th Century right to the start of the 20th, this group of mixed race Middle Eastern Turks, driven by a fanaticism molded in their Muslim religion, occupied vast stretches of central and southern Europe, twice being turned back at the very gates of Vienna in their attempts to seize all of Europe.

The impact and legacy of the Ottomans upon central and southern Europe was therefore vast, and crucial to any understanding of the racial and cultural mix which has made south-eastern Europe the volatile place that it is.

After describing the rise of the Ottomans and their first landings and battles on European soil in the 14th and 15th centuries, including how white resistance failed in the battles of Nicopolis and Varna, Kemp writes about the Janissaries, or “stolen white children” who became the Ottoman elite:

One of the more remarkable ways in which the Ottomans kept their fighting strength up was through a unit of soldiers known as the Janissaries. The Janissaries were the Ottoman’s elite forces—and they were also White.

One of the Ottoman leaders, Emir Orkhan (1326-1359), who was the first to occupy European continental soil, issued an edict to the conquered Europeans in the Balkans that they must hand over to the Ottomans 1,000 White male babies “with faces white and shining” each and every year. The youths were brought before the Ottoman sultan, and the best of them—in terms of physique, intelligence, and other qualities—were selected for education in the palace school. There they converted to Islam, became versed in the Islamic religion and its culture, learned Ottoman Turkish, Persian, and Arabic, and were compelled to serve the Ottomans, with their origins being concealed from them. They became the best and most trusted armed unit within the Ottoman Empire—a supreme act of irony.

This yearly tribute—reminiscent of the demand by the Moors for White virgins from the unfortunate Goths in Spain—was continued for an astonishing 300 years until 1648, during which time not only were 300,000 Whites absorbed into the Ottoman hierarchy (and for the greatest part also into the Turkish elite’s bloodstream) but the Janissaries became known as one of the most efficient army of soldiers in the world.

It is no exaggeration to say that they sustained the Ottoman Empire in Europe for much of its existence, playing a not inconsiderable role in many of the great victories of that Empire.

In 1574, the Janissaries had 20,000 men in their ranks—by 1826 the unit numbered some 135,000. The overtly racial make-up of the Janissaries always created problems of its own. Every now and then, the White soldiers would rebel against their Turkish masters—numerous rebellions are recorded, each being suppressed, until a famous rebellion in 1826 saw the unit finally disbanded, with a large number being killed and the rest dispersed into the broader Turkish population.

Kemp proceeds to explain how Jews were privileged under Turkish Rule; the fall of Constantinople; the war at sea when the Portuguese confronted the Turks; how Belgrade was captured in 1521 AD; the two sieges of Vienna; the Ottoman war with Russia, and finally the brutal destruction of Armenia in 1915-1923:

The region of Armenia, situated on the southeastern banks of the Black Sea, contains one of the most tragic and violent anti-White acts ever committed by the Ottoman Empire. Originally one of the earliest Indo-European homelands, Armenia has some of the oldest iron and bronze smelting and cereal grains sites in the world. Shaken by the flooding of the Black Sea basin around 5600 BC, Armenia was then occupied in quick succession by the early Indo-European Assyrians and Persians.

A period of independence followed, and under their great King Tigranes I (140-55 BC), Armenia established an empire which reached from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean and parts of modern-day Syria. This empire ended with the invasion of that country by the Romans in 69 BC. Armenia then became the first Christian state in the world in AD 301.

Racially speaking, the inhabitants of the region had suffered slight genetic damage in terms of Semitic infusions, but the country was devastated by the 11th Century invasion by the Seljuk Turks, the forerunners of the Ottomans. The Seljuk Turks’ oppressive rule saw a huge number—possibly even a majority—of White Armenians fleeing the country.

The Ottoman Empire, which took over from the Seljuks, instituted an even greater reign of terror against the remaining Armenians, causing further waves of emigration right until the late 19th Century, with many Armenians settling in America.

Those who stayed in Armenia were subject to the most horrendous massacres and persecution, with hundreds of thousands of Armenians being massacred by Turkish forces, culminating in efforts by the Turkish government to move Armenians to Mesopotamia. Between 1915 and 1923 more than one million Armenians died due to the Turkish attempted forced migration.

The remains of Armenians massacred at Erzinjan

By this stage, the vast majority of White Armenians had either emigrated, or had been absorbed into the overwhelming numbers of non-Whites in the Armenia itself, so that today very few original White Armenians remain in the country.

Armenia was therefore a entire country and people who were physically wiped out by the Ottomans, one of the greatest hidden genocides of the Turkish Empire.

The Ottoman legacy

The Ottoman Turks were the last of the Asian invaders of Europe to use violence as their passport of entry, but they were also significant for another reason: the sheer length of the time of their occupation of the Balkans left a large number of the inhabitants of the Balkan peoples with Turkish blood in their veins, as can be seen to this day, as many inhabitants of the region are not only Muslim in faith, but are also distinctly darker than other Balkan residents.

♣

All of these racial wars when whites faced extermination are a fascinating read.

Although the racial wars recounted by Kemp don’t end there, I won’t quote more to invite readers to purchase a hard copy of March of the Titans, an updated 2011 edition of the old online edition I’ve been quoting here (recently removed from the internet).

The fact is that unlike other races whites as a people have been an endangered species more than once, and this has paramount importance to understand our times. Personally, I find it outrageous that so few “white nationalists” are truly interested in the history of the white race; proof of it is that books like this are no bestsellers in the community.

Note:

For excerpts of all chapters of Kemp’s book see: here.

We see the bad message of this episode, in the sense of demoralising the Aryan male, when Jaime Lannister returns from the battle on the Roseroad, still full of mud combat. He tells Cersei that the Dothraki (who ride horses like the Mongols) would defeat any army. The reality is that if the dragon that helped the Dothraki were a metaphor for weapons of mass destruction, it would be the Aryan Lannisters who would have it, not the other side.

We see the bad message of this episode, in the sense of demoralising the Aryan male, when Jaime Lannister returns from the battle on the Roseroad, still full of mud combat. He tells Cersei that the Dothraki (who ride horses like the Mongols) would defeat any army. The reality is that if the dragon that helped the Dothraki were a metaphor for weapons of mass destruction, it would be the Aryan Lannisters who would have it, not the other side.