Below, excerpts from the final

chapter of Nixey’s book:

‘Moreover, we forbid the teaching of any doctrine by those who labour under the insanity of paganism’.

– Justinian Code

The philosopher Damascius was a brave man: you had to be to see what he had seen and still be a philosopher. But as he walked through the streets of Athens in AD 529 and heard the new laws bellowed out in the town’s crowded squares, even he must have felt the stirrings of unease. He was a man who had known persecution at the hands of the Christians before. He would have been a fool not to recognize the signs that it was beginning again.

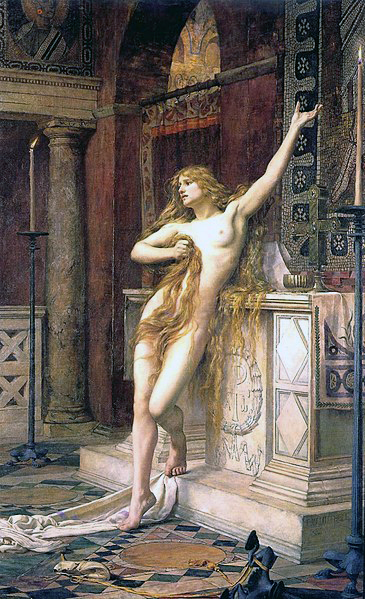

As a young man, Damascius had studied philosophy in Alexandria, the city of the murdered Hypatia. He had not been there for long when the city had turned, once again, on its philosophers. The persecution had begun dramatically. A violent attack on a Christian by some non-Christian students had started a chain of reprisals in which philosophers and pagans were targeted. Christian monks, armed with an axe, had raided, searched then demolished a house accused of being a shrine to ‘demonic’ idols. The violence had spread and Christians had found and collected all images of the old gods from across Alexandria, from the bathhouses and from people’s homes. They had placed them in a pyre in the centre of the city and burned them. As the Christian chronicler, Zachariah of Mytilene, comfortably observed, Christ had declared that he had ‘given you the authority to tread on snakes and scorpions, and over all enemy power’.

For Damascius and his fellow philosophers, however, all that had been a mere prelude to what came next. Soon afterwards, an imperial officer had been sent to Alexandria to investigate paganism. The investigation had rapidly turned to persecution. This was when philosophers had been tortured by being hung up by cords and when Damascius’s own brother had been beaten with cudgels – and to Damascius’s great pride, had remained silent…

Damascius decided to flee. In secret, he hurried with his teacher, Isidore, to the harbour and boarded a boat. Their final destination was Greece, and Athens, the most famous city in the history of Western philosophy.

It was now almost four decades since Damascius had escaped to Athens as an intellectual exile. In that time, a lot had changed. When he had arrived in the city he had been a young man; now he was almost seventy. But he was still as energetic as ever, and as he walked about Athens in his distinctive philosopher’s cloak – the same austere cloak that Hypatia had worn – many of the citizens would have recognized him. For this émigré was now not only an established fixture of Athenian philosophy and a prolific author, he was also the successful head of one of the city’s philosophical schools: the Academy. To say ‘one of’ the schools is to diminish this institution’s importance: it was perhaps the most famous school in Athens, indeed in the entire Roman Empire. It traced its history back almost a thousand years and it would leave its linguistic traces on Europe and America for two thousand years to come. Every modern academy, académie and akademie owes its name it.

Since he had crossed the wine-dark sea, life had gone well for Damascius – astonishingly well, given the turbulence he had left behind. In Alexandria, Christian torture, murder and destruction had had its effect on the intellectual life of the city. After Hypatia’s murder the numbers of philosophers in Alexandria and the quality of what was being taught there had, unsurprisingly, declined rapidly. In the writings of Alexandrian authors there is a clear mood of depression, verging on despair. Many, like Damascius, had left.

In fifth-century Athens, the Church was far less powerful and considerably less aggressive. Its intellectuals had felt pressure nonetheless. Pagan philosophers who flagrantly opposed Christianity paid for their dissent. The city was rife with informers and city officials listened to them. One of Damascius’s predecessors had exasperated the authorities so much that he had fled, escaping – narrowly – with his life and his property. Another philosopher so vexed the city’s Christians by his unrepentant ‘pagan’ ways that he had had to go into exile for a year to get away from the ‘vulture-like men’ who now watched over Athens. In an act that could hardly have been more symbolic of their intellectual intentions, the Christians had built a basilica in the middle of what had once been a library. The Athens that had been so quarrelsome, so gloriously and unrepentantly argumentative, was being silenced. This was an increasingly tense, strained world. It was, as another author and friend of Damascius put it, ‘a time of tyranny and crisis’.

The very fabric of the city had changed. Its pagan festivals had been stopped, its temples closed and, as in Alexandria, the skyline of the city had been desecrated; here, by the removal of Phidias’s great figure of Athena…

Despite his success, Damascius had not forgotten what he had seen in Alexandria – and had not forgiven it, either. His writings show a never-failing contempt for the Christians. He had seen the power of Christian zeal in action. His brother had been tortured by it. His teacher had been exiled by it. And, in the year 529, zealotry was once again in evidence. Christianity had long ago announced that all pagans had been wiped out. Now, finally, reality was to be forced to fall in with the triumphant rhetoric.

The determination that lay behind this threat was not only felt in Athens in this period. It was in AD 529, the very same year in which the atmosphere in Athens began to worsen, that St Benedict destroyed that shrine to Apollo in Monte Cassino…

Previous attacks on Damascius and his scholars had largely been driven by local enthusiasms; a violently aggressive band of Alexandrian monks here, an officious local official there. But this attack was something new. It came not from the enthusiasm of a hostile local power; it came in the form of a law – from the emperor himself…

This was the end. The ‘impious and wicked pagans’ were to be allowed to continue in their ‘insane error’ no longer. Anyone who refused salvation in the next life would, from now on, be all but damned in this one…

This was no longer mere prohibition of other religious practices. It was the active enforcement of Christianity on every single, sinful pagan in the empire. The roads to error were being closed, forcefully. Everyone now had to become Christian. Every single person in the empire who had not yet been baptized now had to come forward immediately, go to the holy churches and ‘entirely abandon the former error [and] receive saving baptism’…

‘Moreover’, it reads, ‘we forbid the teaching of any doctrine by those who labour under the insanity of paganism’ so that they might not ‘corrupt the souls of their disciples.’ The law goes on, adding a finicky detail or two about pay, but largely that is it.

Its consequences were formidable. It was this law that forced Damascius and his followers to leave Athens. It was this law that caused the Academy to close. It was this law that led the English scholar Edward Gibbon to declare that the entirety of the barbarian invasions had been less damaging to Athenian philosophy than Christianity was. This law’s consequences were described more simply by later historians. It was from this moment, they said, that a Dark Age began to descend upon Europe…

Free philosophy has gone. The great destruction of classical texts gathers pace. The writings of the Greeks ‘have all perished and are obliterated’: that was what John Chrysostom had said. He hadn’t been quite right, then: but time would bring greater truth to his boast. Undefended by pagan philosophers or institutions, and disliked by many of the monks who were copying them out, these texts start to disappear. Monasteries start to erase the works of Aristotle, Cicero, Seneca and Archimedes. ‘Heretical’ – and brilliant – ideas crumble into dust. Pliny is scraped from the page. Cicero and Seneca are overwritten. Archimedes is covered over. Every single work of Democritus and his heretical ‘atomism’ vanishes. Ninety per cent of all classical literature fades away…

The pages of history go silent. But the stones of Athens provide a small coda to the story of the seven philosophers… The lovely statue of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, suffered as badly as the statue of Athena in Palmyra had. Not only was she beheaded she was then, a final humiliation, placed face down in the corner of a courtyard to be used as a step. Over the coming years, her back would be worn away as the goddess of wisdom was ground down by generations of Christian feet.

The ‘triumph’ of Christianity was complete.