Yesterday’s post by Chris White criticising Millennial Woes has given me an idea. I have not tired of punching left since, exactly six years ago (November 22, 2011), I started criticising Greg Johnson because of his promotion of degenerate music at his webzine.

Question: Any other interested in criticising here the Alt-Right? Many of us are fed up with them, as can be seen in this pivotal article.

Author: C .T.

Below, abridged translation from the first

volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte

des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity)

Christian tall stories

Christians, preachers of love of the enemy and of the doctrine that all authority emanates from God, celebrated the death of the emperor with great public banquets, with festivals in churches and chapels and dances in the theatres of Antioch: the city that, as Ernest Renan says, ‘was full of puppeteers, charlatans, actors, magicians, thaumaturges, witches and religious swindlers’.

The diatribe in three volumes that Julian had written shortly before his death, Against the Galileans, was promptly destroyed, but fifty years later, Cyril, the doctor of the Church still bothered to argue against it: Pro sanela Christianorum religione adversas libros athei Julian in thirty volumes, of which ten have reached us in their Greek text and ten others in Greek and Syriac fragments. Naturally, a bishop like Cyril, an avowed enemy of philosophy who even tried to prohibit its teaching in Alexandria, did not intend to grasp the thought of Julian, but only ‘crush it with maximum energy’ (Jouassard).

The Christians also destroyed all the portraits of Julian and the epigraphs that commemorated his victories, without sparing means to erase from the memory of men the remembrances of him.

During Julian’s life, the most famous doctors of the Church had kept a prudent silence, but shortly after his death, and for a long time more, they dedicated themselves to attacking him.

Ephrem, another saint whose odious songs were repeated by the parishioners of Edessa, dedicated a whole treatise to ‘Julian the Apostate’, the ‘pagan emperor’ and, according to him, ‘frantic’, ‘tyrant’, ‘trickster’, ‘damned’ ‘and’ idolatrous priest’. ‘His ambition caught the deadly release’ that ‘tore his body pregnant with oracles from his magicians’ to send him definitively ‘to hell’. The clerical historians of the 5th century, who sometimes were also jurists, such as Rufinus, Socrates, Philostorgius, Sozomen and Theodoret, speak of Julian in a still worse tone.

While the Christian world defamed the ‘apostate’, as he usually does with its enemies, the Enlightenment corrected that image in the diametrically opposite sense.

In 1699, the Protestant theologian Gottfried Arnold, in his Impartial History of the Church and of Heresy, rehabilitated the figure of Julian.

A few decades later, Montesquieu praised him as a statesman and legislator. Voltaire wrote: ‘Thus, that man who has been described to us horribly was perhaps the most noble of all, or at least the second’. Montaigne and Chateaubriand count him among the greatest historical figures.

Goethe praised himself for understanding and sharing Julian’s animosity against Christianity. Schiller wanted to make him protagonist of one of his dramas.

Shaftesbury and Fielding praised him, and Gibbon believes that he deserved to have owned the world. Ibsen wrote Caesar and Galilee and Nikos Kazantzakis his tragedy Julian the Apostate, premiered in Paris in 1948.

More recently, between 1962 and 1964, the North American Gore Vidal dedicated a novel to him. On the other hand, the Benedictine Baur (representative, in this, of many current Catholics) continues to defame Julian in the 20th century.

After the death of Julian, and having renounced the designated successor, Salutius, a moderate pagan philosopher and prefect of the praetorians of the East who had been a personal friend of Julian, the Illyrian Jovian acceded to the throne.

Editor’s note: Chris White, who appeared last month on WDH Radio Show, is now responding to yesterday’s effete video by Millennial Woes:

Hailgate? You mean a few guys giving roman salutes in front of Richard Spencer? Are you kidding? What do you want? A reverse nanny state?…

Hailgate? You mean a few guys giving roman salutes in front of Richard Spencer? Are you kidding? What do you want? A reverse nanny state?…

I just typed in ‘Hailgate’ into Google and all I got as the top search results was a small village in North Yorkshire. That was an interesting experience.

Your whinging is preposterous. Biased government-media sponsored lawsuits and political arrests and intimidation are all apart and parcel of being in a political resistance movement you fool.

You should have seen this coming from a mile off, so why isn’t The Alt-Right prepared for it? If The Alt-Right is on a dip at the moment well then this is to be expected given Trump’s ascendance to the White House; it probably has nothing or very little to do with ‘Nazis’ and your patent submission to The Left’s cultural terrorism. If as you say The Alt-Right is ‘failing’ then this is most likely due to the very internalised nanny state tactics and hermitry that you now propose.

A real political resistance organisation would be establishing independent undercover mutually supporting bureaus in every city to monitor and log enemy activity, and to compile lists of both state and non-state enemy actors; would be pooling resources in order to buy up and make money from property; and would be covertly investing in shares and bonds through anonymous agents.

If The Alt-Right is really serious then why isn’t there a list of all public sector workers, their ID’s and home addresses? Where are the lists of journalists and their places of work? Why aren’t there any data gathering operations against the Liberal press and mainstream political parties?

What else do you seem to be advocating for other than yet more boring quasi-homoerotic meetings and conferences where you can all insulate yourselves from the reality outside in a meaningless bubble of time-warped pomposity? I just clocked the disclaimer on this completely unnecessary video: ‘This video is not intended to condone violence or hate’.

This is pathetic. This is not the type of attitude that I would expect from someone who aspires to become a political leader explicitly advocating for freestanding White interests. It is not ‘Nazism’ that has caused The Alt-Right streamliner to run out of steam against the tide, it is the very intellectual masturbation and kosherism that you are now urging us all to adopt.

Note of November 25, 2017: I’ve just changed the title of this article from “available again” to “unavailable as hard copy”. However, this site hosts a PDF of the book that can be printed in your home (see sidebar). Below, the original post:

______ 卐 ______

It now seems that Lulu Press Inc. vaporised my account because James Mason’s Siege was selling well. I deduce this because Storefront Books’ Lulu account was also ‘vaporised’ (an Orwellian term). Of course: The social media, mostly companies led by Jews, are inventing politically-correct laws of their own. In America the PC enforcer is not a government that still maintains First Amendment rights. For example, the 1969 Brandenburg v. Ohio allows talking seriously about revolution unless you’re already promoting immediate use of violence, call for arms, etc. Therefore, Siege should be legal in the US.

I didn’t receive any warning about the vaporisation. Had I received it I’d have saved the PDF of the English-German translation of Hunter that only my Daybreak published (I hope a German friend has kept his backup copy safe!). Also, had I received a notice of the termination I’d have written down the stats of how many copies Lulu sold of my books in Spanish since 2011 (of which Day of Wrath is only a selection in English). Now I will never know.

In the novel 1984 vaporisation of people occurs without any warning. If my WordPress account that hosts the present site is vaporised you still can find me through my Wikipedia user page. As you can see, the last words of that page say, ‘So I moved on, outside the wiki’ linking to a quotable quote in this site. If my WP account is abruptly terminated in the future, the italicised words above will be linked to my new address of The West’s Darkest Hour.

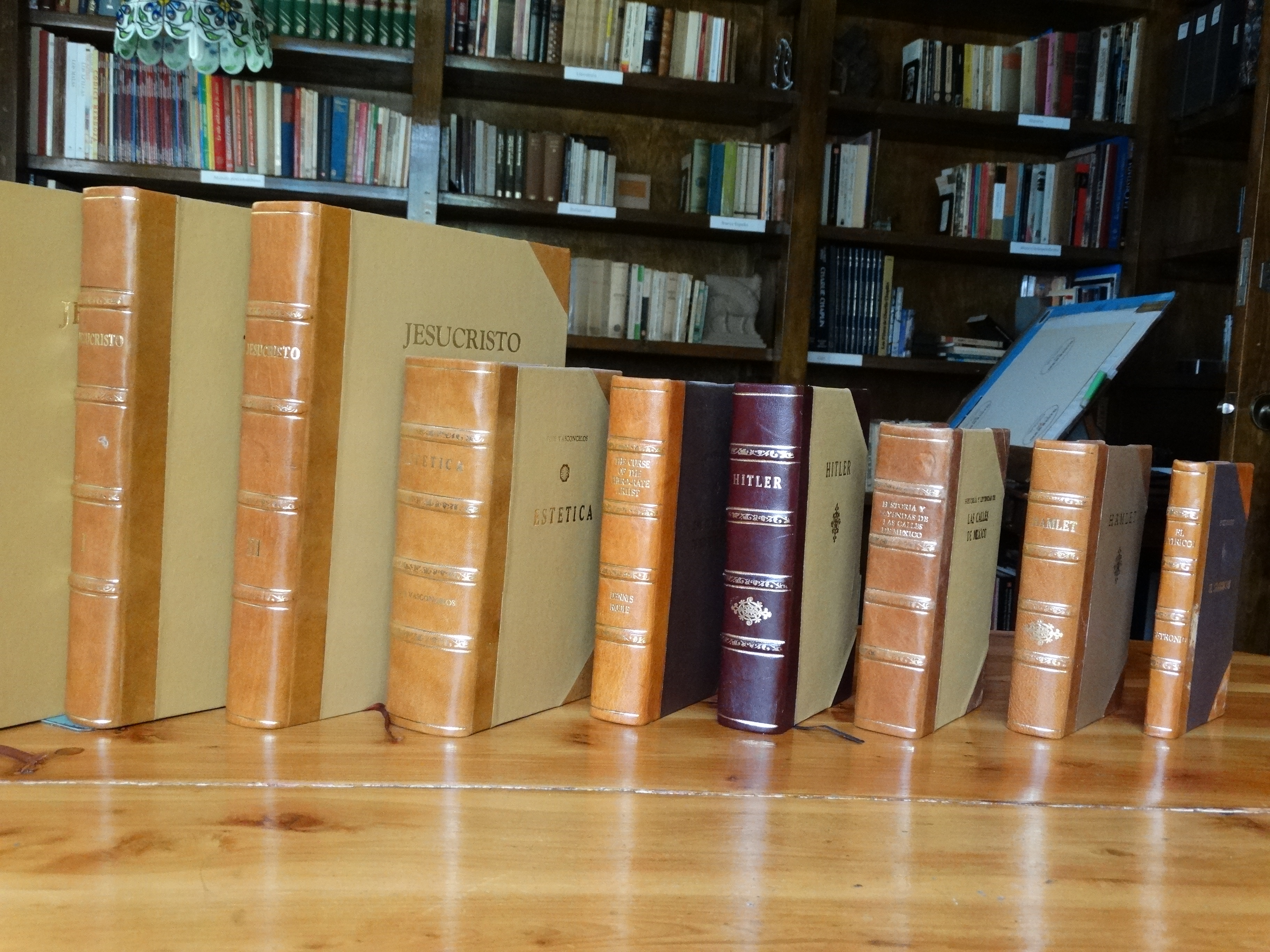

In the previous post ‘Daybreak partner?’ I said I’d visit my traditional bookbinder. We talked last Saturday and he showed me his equipment. Now I know an approximation of what it would cost me to obtain a similar set to print books at home. For the moment I cannot afford it but I must sincerely thank our overseas sponsor whose generous contribution has allowed me to get sufficient toner cartridges to print whole books (and then take the ordered stack of paper sheets to my bookbinder).

For the moment the books he and I will manufacture will look like this:

Only if the business flies we may add, in the future, dust covers for these hardcover books. Incidentally, I have changed the colour and title of my ‘Addenda’ page to ‘Daybreak Publishing’ and will be modifying the page in the coming days.

Only if the business flies we may add, in the future, dust covers for these hardcover books. Incidentally, I have changed the colour and title of my ‘Addenda’ page to ‘Daybreak Publishing’ and will be modifying the page in the coming days.

My hunch is that only Siege will be censored if I request the services of another print-on-delivery company to host my Daybreak books. So I’ll keep the making of Mason’s great book exclusively for the shop (see: here).

But I guess other books won’t be censored. The Fair Race’s Darkest Hour for example has not made a single bleep in the PC radar, so I am prepared to take a chance in opening an account elsewhere for most of my Daybreak titles.

Any recommendation for another print-on-delivery service now that Lulu has failed us?

Julian, 18

Julian presiding at a conference of Sectarians

(Edward Armitage, 1875)

My interview with Constantius occurred on the last day of his visit. Bishop George spent the morning coaching us in what to say. He was as nervous as we were; his career was at stake, too.

Gallus was admitted first to the sacred presence. During the halfhour he was with the Emperor, I recall praying to every deity I could think of; even then I was eclectic!

At last the Master of the Offices, gorgeous in court robes, came to fetch me. He looked like an executioner. Bishop George rattled out a blessing. The Master gave me instructions in how I was to salute the Emperor and which formula of greeting I was to use. I muttered them over and over to myself as I swam—that was my exact sensation—into the presence of the Augustus.

Constantius was seated on an ordinary chair in the apse of the hall. Eusebius stood beside him, holding a sheaf of documents. On a stool at Constantius’s feet sat Gallus, looking well-pleased with himself.

I went through the formula of homage, the words falling without thought from my lips. Constantius gave me a long, shrewd, curious look. Then he did not look at me again during the course of the interview. He was one of those men who could never look another in the eye. Nor should this characteristic be taken, necessarily, as a sign of weakness or bad conscience. I am rather like Constantius in this. I have always had difficulty looking into men’s eyes. All rulers must. Why? Because of what we see: self-interest, greed, fear. It is not a pleasant sensation to know that merely by existing one inspires animal terror in others. Constantius was often evil in his actions but he took no pleasure in the pain of others. He was not a Caligula, nor a Gallus.

Constantius spoke to me rapidly and impersonally. “We have received heartening reports concerning the education of our most noble cousin Julian. Bishop George tells us that it is your wish to prepare for the priesthood.” He paused, not so much to hear what I might say as to give proper weight to what he intended to say next. As it was, I was speechless.

Constantius continued, “You must know that your desire to serve God is pleasing to us. It is not usual for princes to remove themselves from the world, but then it is not usual for any man to be called by heaven.” I suddenly saw with perfect clarity the prison I was to occupy. Deftly, Constantius spun his web. No priest could threaten him. I would be a priest.

“Bishop George tells me that you have pondered deeply the disputes which—sadly—divide holy church. And he assures me that in your study of sacred matters you have seen the truth and believe, as all Christians ought, that the son is of like substance to the father, though not of the same substance. Naturally, as one of our family, you may not live as an ordinary holy man; responsibilities will be thrust upon you. For this reason your education must be continued at Constantinople. You are already a reader in the church. In Constantinople you can hope to become ordained, which will give us pleasure, as well as making you most pleasing to God who has summoned you to serve him. And so we salute our cousin and find him a worthy descendant of Claudius Gothicus, the founder of our house.”

That was all. Constantius gave me his hand to kiss. I never said a word beyond those required by court ceremonial. As I backed out of the room, I saw Gallus smile at Eusebius.

I wonder now what Constantius was thinking. I suspect that even then I may have puzzled him. Gallus was easily comprehended. But who was this silent youth who wanted to become a priest? I had planned to say all sorts of things to Constantius, but he had given me no opportunity. Surprisingly enough, he was nervous with everyone. He could hardly speak, except when he was able to speak, as it were, from the throne. Excepting his wife, Eusebia, and the Grand Chamberlain, he had no confidants. He was a curious man.

Now that I am in his place I have more sympathy for him than I did, though no liking. His suspicious nature was obviously made worse by the fact that he was somewhat less intelligent than those he had to deal with. This added to his unease and made him humanly inaccessible. As a student he had failed rhetoric simply through slowness of mind. Later he took to writing poetry, which embarrassed everyone. His only “intellectual” exercise was Galilean disputes. I am told that he was quite good at this sort of thing, but any village quibbler can make a name for himself at a Galilean synod. Look at Athanasius!

I was relieved by this interview. Of course I did not want to become a priest, though if that were the price I had to pay for my life I was perfectly willing to pay it.

In a blaze of pageantry, Constantius departed. Gallus, Bishop George and I stood in the courtyard as he rode past. Mounted, he looked splendid and tall in his armour of chased gold. He acknowledged no one as he rode out of Macellum. In his cold way he was most impressive, and I still envy him his majesty. He could stand for hours in public looking neither to left nor right, motionless as a statue, which is what our ceremonial requires.

It was the Emperor Diocletian who decided that we should become, in effect, if not in title, Asiatic kings, to be displayed on rare occasions like the gilded effigies of gods. Diocletian’s motive was understandable, perhaps inevitable, for in the last century emperors were made and unmade frivolously, at the whim of the army. Diocletian felt that if we were to be set apart, made sacred in the eyes of the people and hedged round by awe-inspiring ritual, the army would have less occasion to treat us with easy contempt.

To a certain extent, this policy has worked. Yet today whenever I ride forth in state and observe the awe in the faces of the people, an awe inspired not by me but by the theatricality of the occasion, I feel a perfect impostor and want to throw off my weight of gold and shout, “Do you want a statue or a man?” I don’t, of course, because they would promptly reply, “A statue!”

As we watched the long procession make its way from the villa to the main highway, Gallus suddenly exclaimed, “What I’d give to go with them!”

“You will be gone soon enough, most noble Gallus.” Bishop George had now taken to using our titles.

“When?” I asked.

Gallus answered. “In a few days. The Emperor promised, ‘When all is ready, you will join us.’ That’s what he said. I shall be given a military command, and then…!” But Gallus was sufficiently wise not to mention his hopes for the future. Instead he gave me a dazzling smile. “And then,” he repeated, with his usual malice, “you’ll become a deacon.”

“The beginning of a most holy career,” said Bishop George, removing his silver headdress and handing it to an attendant. There was a red line around his brow where the crown had rested. “I wish I could continue with your education myself, but, alas, the divine Augustus has other plans for me.” For an instant a look of pure delight illuminated that lean, sombre face.

“Alexandria?” I asked. He put his finger to his lips, and we went inside, each pleased with his fate: Gallus as Caesar in the East, George as bishop of Alexandria, and I… well, at least I would be able to continue my studies; better a live priest than a dead prince.

For the next few weeks we lived in hourly expectation of the imperial summons. But as the weeks became months, hope slowly died in each of us. We had been forgotten.

Bishop George promptly lost all interest in our education. We seldom saw him, and when we did his attitude was obscurely resentful, as if we were in some way responsible for his bad luck. Gallus was grim and prone to sudden outbursts of violence. If a brooch did not fasten properly, he would throw it on the floor and grind it under his heel. On the days when he spoke at all, he roared at everyone. But most of the time he was silent and glowering, his only interest the angry seduction of slave girls.

I was not, I confess, in the best of spirits either, but at least I had Plotinus and Plato. I was able to study, and to wait.

Emperor Julian

(Flavius Claudius Iulianus Augustus)

Caesar: 6 November 355 – February 360

Augustus: February 360 – 3 November 361

Sole Augustus: 3 November 361 – 26 June 363

The pagan reaction under Julian

Like his brother Gallus, Julian was also spared from the killing of relatives, although as a member of the imperial dynasty he was kept closely guarded: first in a magnificent estate of Nicomedia, which had been owned by his mother (Basilina, deceased shortly after the birth of Julian), and then in the lonely fortress of Macellum, located in the heart of Anatolia, where his older brother was also imprisoned. The distrustful emperor wove a dense network of spies around both princes, to transmit him each and every one of their words.

They lived ‘like prisoners in that Persian castle’ (Julian), practically arrested and surely threatened with death. In Nicomedia, Julian was given a preceptor, Bishop Eusebius, a relative of Basilina, ecclesiastic and man of the world already known at the time, who, following the custom of Oriental prelates, used to dye his nails with cinnabar and his hair with henna. He was instructed to educate the child severely in the Christian religion; to prevent him from contacting the population, and to ‘never talk about the tragic end of his family’, although at seven Julian was very aware of it and this caused frequent crying spells and terrible nightmares.

In Macellum, where he was confined for seven years with scarcely any other company than that of his slaves, he had as his educator the Arian Jorge of Cappadocia, who was in charge of training him for the priesthood. But then Julian was able to leave the place and settled in Constantinople, where he lived the disputes between Arians and Orthodox and knew the real life of that world of violent riots and fiery mutual excommunications. Towards the end of 351, when Julian was twenty years old, Constantius ordered him to continue his studies in Nicomedia. Julian visited Pergamum, Ephesus and Athens, where he had notable teachers who won him for paganism.

Appointed caesar in 355 by Constantius, and proclaimed augustus by the army in Paris in 360, the same sovereign, who had no offspring, at the time of death appointed Julian as successor… when the two opposing armies marched to the encounter of the other. An ephemeral restoration of polytheistic traditions took place, with the establishment of a Hellenistic ‘state religion’, whose organization followed in many respects the pattern of Christian canons.

Julian tried to replace the cross and the nefarious dualism of Christians by a formula composed of certain streams of Hellenistic philosophy and a ‘solar pantheism’. Without neglecting the other gods of the pagan pantheon, he had a temple built for the Sun god—probably identified with Mithra—in the imperial palace; on numerous occasions he proclaimed his veneration for the basileus Helios, the Sun king, which was already a bi-millennial tradition:

Since my childhood, I was inspired by an invincible longing for the rays of the God, who have always captivated my soul, in such a way that I constantly wanted to contemplate it and even at night, when I was in the country, I forgot everything to admire the beauty of starry heaven…

Today we have become accustomed to interpreting Julian’s reaction as a nostalgic movement, a romantic anachronism or the absurd attempt to turn the hands of the clock backwards. But why do we interpret it that way? Was he refuted, or could he be, instead of being drowned in blood? What is certain and undeniable is that Emperor Julian (from 361 to 363), called ‘the Apostate’ by the Christians, was far superior to his Christian predecessors in character, morality and spirituality.

Trained in philosophy and literature, not only was he ‘the first truly cultured emperor for more than a century’ (Brown), but also deserved ‘a prominent place among writers of the time in the Greek language’ (Stein), and he knew to surround himself with the best thinkers of his time. Julian was zealous in the fulfilment of his duty and enemy of all gentleness, since he never had mistresses or ephebes, never got drunk; the emperor went to work since dawn. He tried to rationalise the bureaucracy and place intellectuals in top government and administrative positions.

Julian abolished the splendours of the court, the possession of eunuchs and jesters, and the whole system of flatterers, parasites, spies and whistleblowers who were fired by the thousands. He reduced the service, reduced the taxes by a fifth, acted with severity against the unfaithful collectors and sanitized the state mail. He also abolished the labarum, that is, the banner of the army with the anagram of Christ, and tried to resurrect ancient cults, festivals and the Paideia: classical education. He ordered the return of the old temples or the reconstruction of those that had been destroyed, and even the return of the statues and other sacred ornaments that adorned the gardens of the individuals who had appropriated them.

But he did not ban Christianity; on the contrary, he allowed the return of the exiled clerics, which only served to foment new conspiracies and tumults.

The Donatists of Africa, while praising the emperor as a paragon of justice, disinfected their newly recovered churches by scrubbing them up and down with sea water, sanded the wood of the altars and the plaster of the walls, regained the influence lost under Constans and Constantius II, and prepared to enjoy their revenge. The Catholics were converted by force, their churches expropriated, their books burned, their chalices and monstrances thrown by the windows and the hosts thrown to the dogs; some abused clerics died. Up to 391, the Donatists continued to have high status, at least in Numidia and Mauritania.

It is true that Julian, as a supporter of polytheism, criticized the Old Testament and its monotheistic rigours, as well as the arrogance of the supposed chosen people, but he granted Yahweh a rank equal to that of the other gods and even admitted that the God worshiped by the Jews was ‘the best and most powerful of all’. A Jewish delegation that visited him in Antioch in July 362, obtained the authorization to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem and the promise of new territories, in a kind of anticipation of the current ‘Zionism’, which motivated the jubilation of the diaspora. The reconstruction of the temple was initiated with great eagerness the following spring, while Julian undertook his campaign in Persia, but towards the end of May a fire, judged ‘providential’ by the Christians, as well as the death of Julian, meant the end of the works forever.

Julian was always in favour of tolerance, even towards Christians. If his dispositions regarding the ‘Galileans’, he said on one occasion, were benign and humanitarian, they should reciprocate by not bothering anyone, nor trying to impose assistance on their churches. In a letter to the citizens of Bosra, he wrote:

To convince and to teach men, it is necessary to use reason and not blows, threats or corporal punishment. I will not tire of repeating it: if you are sincere supporters of the true religion, you will refrain from bothering, attacking or offending the community of the Galileans, who are more worthy of pity than hatred, since they are wrong in matters of such power and transcendence.

Now, and although Julian was a supporter of tolerance… he could not avoid the use of violence against the violent, the Christians who were dedicated to desecrating and even destroying the newly rebuilt temples in Syria and Asia Minor, as well as statues. His legislation in the matter of education provoked many hatreds, inasmuch as he forbade Christians to study Greek literature (saying ‘let them stay in their churches interpreting their Matthew and Luke’). He also demanded the return of the columns and capital stolen from the temples by the Christians to adorn their ‘houses of God’.

If the Galileans want to have decoration in their temples, congratulations, but not with the materials belonging to other places of worship.

Libanius tells how the ships and chariots that returned their columns to the sacked gods could be seen everywhere. On October 22, 362, the Christians set fire to the temple of Apollo in Daphne, which had been restored by the sovereign, and destroyed the famous statue. In retaliation, Julian had the Basilica of Antioch and other churches consecrated to various martyrs razed. (Incidentally, Christians said that the temple had been struck by lightning but according to Libanius, there were no storm clouds on the night of the fire.)

In Damascus, Gaza, Ashkelon, Alexandria and other places the Christian basilicas burned, sometimes with the collaboration of the Jews; some believers were tortured or killed, including Bishop Marcus de Arethusa, so he entered the payroll of the martyrs. But, in general lines, ‘more offended had been the rights of the pagans’ (Schuitze), and in any case said pogrom was no more than a reaction to the excesses of the Christians, their abuses and their diatribes against paganism.

Throughout the empire, from Arabia and Syria, through Numidia, and even the Italian Alps, Julian was celebrated as a ‘benefactor of the state’, ‘undoing past wrongs’, ‘restorer of temples and the empire of freedom’, ‘magnanimous inspirer of the edicts of tolerance’. Even one of Julian’s main intellectual detractors, Gregory of Nazianzus, confessed that his ears ached from hearing so much praise from his liberal regime, according to Ernst Stein, ‘one of the healthiest the Roman Empire ever had’.

During the campaign in Persia, initiated by the emperor from Antioch (which was the main base of operations of the Romans against the Persians), on March 5, 363, a favourable occasion was presented. Julian, who was not wearing a breastplate, fell north of Ctesiphon, on the banks of the Tigris. Why was he unarmed? Was he wounded by an enemy spear or, as some claim, from his own ranks? Nobody knew.

Libanius, who was friend of Julian, assures that the author was a man ‘who refused to render cult to the Gods’. And even a Christian historian claims that Julian died at midnight on June 26, 363, when he was thirty-two years old and had governed for twenty months, victim of an assassin in the pay of the Christians…, a hero without blemish, naturally, who ‘perpetrated this audacious action in defence of God and religion’.

The Persians argued that he could not be one of their own, because they were out of range when the emperor was wounded in the midst of his troops. ‘Only one thing is certain’, Benoist-Méchin wrote, ‘and it is that he was not a Persian’, although he does not provide any definitive proof. ‘Be that as it may’, wrote Theodoret, father of the Church, ‘was he man or angel who wielded the sword, the truth is that he acted as the servant of the divine will’.

Further to ‘Lulu has deplatformed me’. Yesterday I phoned my traditional bookbinder. Before I used the services of Lulu this man used to assemble a stack of paper sheets of my Hojas Susurrantes. I made an appointment with him for tomorrow to ask prices of bookbinding equipment.

Yesterday I also accompanied a family member for a long queue at the hospital and brought with me a copy of Rockwell’s This Time the World. The available edition of this book at Amazon Books is of poor quality, both the covers and the lack of care in the formatting of the interior. Just for carrying it to the hospital and reading it there, the covers bended making an outward curve that denoted the poor quality of the cover.

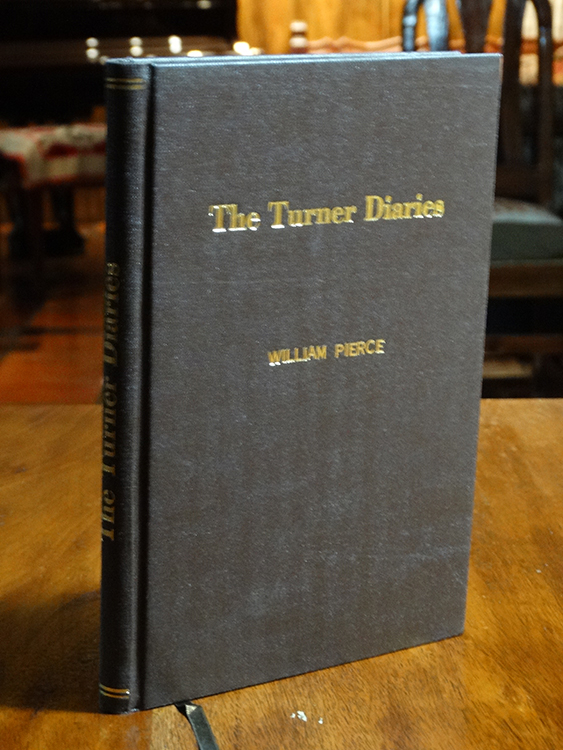

This is a copy The Turner Diaries I requested to assemble. I was outraged that the paperback copies of Pierce’s immortal novel available through Amazon were marred by a politically correct preface of someone who excoriated the content. So dismayed that I tore off the soft cover and the insulting preface and took it to the shop. Now it’s one of the books I can treasure of my personal library.

This is a copy The Turner Diaries I requested to assemble. I was outraged that the paperback copies of Pierce’s immortal novel available through Amazon were marred by a politically correct preface of someone who excoriated the content. So dismayed that I tore off the soft cover and the insulting preface and took it to the shop. Now it’s one of the books I can treasure of my personal library.

We need a homely way of publishing hardcover books that may be sold as print-on-delivery services. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a handsome edition of the excerpted translation to English of Deschner’s first volume of Kriminalgeschichte des Christentums once I finish it by the end of the year?

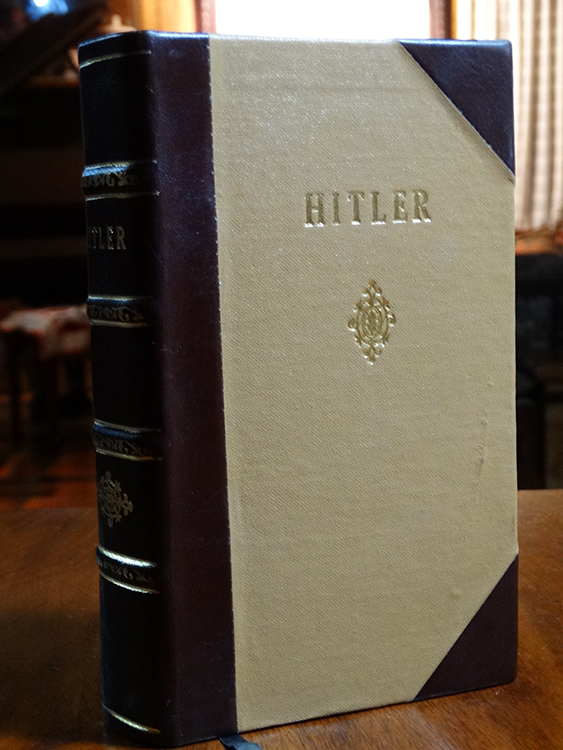

With the proper equipment we could even make deluxe editions. This for example is my copy of Mein Kampf assembled with the same tools of the bookbinder I’ll visit tomorrow. Other colours are possible. He also assembled a copy of Esau’s Tears which comercial cover I had torn off. (Incidentally, that book recounts how the subversive tribe took over the presses in Europe throughout the 19th century.)

With the proper equipment we could even make deluxe editions. This for example is my copy of Mein Kampf assembled with the same tools of the bookbinder I’ll visit tomorrow. Other colours are possible. He also assembled a copy of Esau’s Tears which comercial cover I had torn off. (Incidentally, that book recounts how the subversive tribe took over the presses in Europe throughout the 19th century.)

Of course: the shop can also assemble my books in Spanish that I had printed at home. Presently I use Garamond font with #12 size-letters for a comfortable reading. Royal size for long books or standard size for shorter books seem reasonable to me.

We must not let the Jews monopolise the press, let alone our classics! Deplatforming is only possible because of Jewish monopoly over the publishing houses. While the homely Noontide Press in the US and Ostara Publications in the UK are doing well in softcover format, those books of paramount importance merit hardcover editions that may last for generations in our family libraries.

If someone wants to be a partner in Daybreak Publications to allow me purchase the equipment, in addition to sharing revenues he will also choose the best titles for the collection. Meanwhile I must limit myself to pay the services of my traditional bookbinder to assemble the books that still appear on the sidebar and send them internationally trough mail to those interested in obtaining a copy of any of them.

Below, abridged translation from the first

volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte

des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity)

First assaults on the temples

Paganism still had many followers among the peasants, the many rectors and philosophers; it was also preserved among the cultivated aristocracy, especially the most rancid senatorial families, even among those of the Eastern empire.

In the year 341, a decree attributed to Constans began not with the classic exposition of motives, but with a propagandistic cry: ‘Let the superstition cease! May the delirium of sacrifices be abolished!’ (caesat superstitio sacrificiorum aboleatur insania). Consequently, the sovereign ordered in 346 the closing, with immediate effects, of the temples located in the cities; in 356, the closing of all the temples was ordered.

The question was to prevent the wicked (perditi) from doing their bad things, which triggered a wave of assaults on the temples. The confiscation of property and death by stepping on a temple, or by participating in the ‘aberration’ of sacrifices or worshiping an image, was one of the points of the laws of Constantius: ‘Whoever such things do, be struck down by the avenger sword’.

Libanius, a pagan Hellene rector of Antioch, wrote that Constantius inherited from his father ‘the spark of the inclination to evil deeds, converted by him into a great fire, because he plunders the treasures of the gods, demolishes the temples, annuls the sacred canons’. Libanius comments that Constantius ‘generalized to the rhetoric (logoi) the contempt of pagan worship, and it is not surprising, because both, worship and rhetoric are related and go together’. The contemporary reader will understand that with this he accused the emperor of going against religion and against classical culture at the same time.

The most fanatical Christians already attacked altars and temples. The deacon Cyril of Heliopolis, for example, became famous with his actions. In Arethusa of Syria, the priest Marcus made to demolish an old sanctuary (what later, being bishop and during the reaction of Julian, it was worth a serious beating). In Caesarea of Cappadocia, the Christian community razed a temple of Zeus, patron of the city, and another of Apollo. In Alexandria, the Arian Georgios destroyed a whole series of sacred places of paganism.

Hecatombs under the pious Gallus

(Constantius Gallus in a late copy of 354.) In Palestine, the scene of the process of Scythopolis, occurred the outrages of Gallus, a cousin of Constantius who was saved from the dynastic slaughter of the year 337. We find here another good Christian, assiduous to the church since childhood, great reader of the Bible and supposedly faithful husband of the old Constantina, sister of the emperor and married in second nuptials: a notorious harpy, ‘an unleashed fury’, Amianus wrote, ‘as bloodthirsty as his own husband’.

(Constantius Gallus in a late copy of 354.) In Palestine, the scene of the process of Scythopolis, occurred the outrages of Gallus, a cousin of Constantius who was saved from the dynastic slaughter of the year 337. We find here another good Christian, assiduous to the church since childhood, great reader of the Bible and supposedly faithful husband of the old Constantina, sister of the emperor and married in second nuptials: a notorious harpy, ‘an unleashed fury’, Amianus wrote, ‘as bloodthirsty as his own husband’.

Gallus sent his brother Julian several letters of reprimand, inviting him to return to Christianity. In 351, the year of his proclamation as Caesar, Gallus scandalized the pagans by carrying the bones of Saint Babylas—incidentally, the first well-documented relocation we know—to the famous Apollo sanctuary in Daphne, which was thus rendered denaturalized.

The Christian Gallus, a great fan of boxing (at that time boxing was very bloody, with frequent breaking of bones), was revealed as a little tyrant in his residence of Antioch, through arbitrariness of all kinds and trials for high treason and witchcraft in which he made fun of all the legal norms and that brought a wake of confiscations, exile, horrible tortures and executions.

The fight against the pagans was tinged with true fanaticism, and he used a network of spies that covered the entire city. The Caesar Gallus, of whom Theodoret says with emphasis that ‘he was orthodox to death until the day of his death’, even induced some lynching by the plebs to get rid of certain uncomfortable fellow citizens. In 352, when the Jews suffered another of their periodic attacks of messianic excitement and rebelled against the prohibition of having slaves who were not Jews, assaulting a Roman garrison to procure weapons and naming someone of name Patrician, the pious Gallus burned entire cities and cut the throats even of the children.

Nor were the high imperial officials saved from this regime of terror; thus it fell the prefect of the East, Thalasius, directly responsible to the emperor. He was succeeded by Domitian, who shortly after his arrival in Antioch was captured by the soldiers, dragged through the streets, hung by his legs and thrown into the river Orontes; the same end suffered his quaestor.

There were several other murders, and towards the beginning of the summer of 354 the population rose ‘for varied and complicated reasons’, as Ammianus writes, but above all because of famine and general misery. Governor Theophilus was killed and dismembered.

Constantius was in need of calling his cousin, despite having promised him full immunity, and asked him to be accompanied by his wife, ‘the lovely Constantina’, since he had not seen her for a long time. Gallus understood that there was something fishy, but he trusted the support of Constantina, the emperor’s sister.

But this supporter died in those days as a result of a fever and the emperor beheaded his man of confidence one autumn morning in 354, in Istria. After the execution he proceeded with the rack, the axe of the executioner or exile against all the friends of Gallus, his officers and officials, and even against some religious people.

Only the death of the sovereign, at forty-four years of age on November 3, 361, avoided Constantius a confrontation with his cousin Julian.

Lulu Press, Inc., which had been publishing my books (most of them listed on the sidebar but even those in Spanish), has nuked my account. I have communicated with them. It looks like termination has to do with what they call ‘Questionable content’:

This includes content that Lulu’s deems to promote… discrimination against others based solely on race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender and gender identity…

This means that I should try to start a small publishing house (like e.g., Counter-Currents Publishing). Otherwise, if I go for example to Amazon for another print-on-delivery service, they may also terminate my account after some time (as happened to Arthur Kemp’s Ostara Publications).

C.T.

Below, abridged translation from the first

volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte

des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity)

A father of the Church who preaches looting and killing

And it was time for Firmicus Maternus, who expressed with joy that ‘although in some regions the dying members of idolatry still revolt, the complete eradication of such a pernicious aberration in all the Christian provinces’ seems near, which served to launch this proclamation to the Christian emperors: ‘Out with all the pagan ornaments of the temples! To the mint and the crucible with the metal of the idolatrous statues, so that they melt in the heat of the flames!’

In the diatribe De errore profanarum religionum (“On the error of profane religions”), written about the year 347, Firmicus incites emperors Constans and Constantius, called ‘sacratissimi imperatores’ and ‘sacrosancti’ to the extermination, above all, of mystery cults: the most dangerous for Christianity. These were the cults of Isis, Osiris, Serapis, Cybele and Attis, Dionysus-Bacchus and Aphrodite, and the solar cult of Mithraism, the most powerful of the time, characterized by numerous and surprising parallels with the Christian religion.

Many Catholic authors still deny (despite having proved incontestably in 1897) that Firmicus was the author of those bloodthirsty diatribes, which are discredited by their fanatical style full of pleonasms, prototype of future Catholic rhetoric and pamphlets.

Many Catholic authors still deny (despite having proved incontestably in 1897) that Firmicus was the author of those bloodthirsty diatribes, which are discredited by their fanatical style full of pleonasms, prototype of future Catholic rhetoric and pamphlets.

Christ, the father of the Church congratulates himself, ‘he has knocked down the column where the devil had his image’, which appears thus ‘almost defeated, turned into fire and ashes’. ‘Little is left now for the devil, totally overwhelmed by your laws, to be totally destroyed, putting an end to the disastrous contagion, once the worship of idols, that poison has been exterminated. Celebrate with jubilation the annihilation of paganism, sing in full voice the hallelujah, for you have won as soldiers of Christ’.

Not yet, however. The religiones profanae still existed, almost all the temples still stood and the pagans still came to their sanctuaries. For this reason, the agitator demands the confiscation of their property, the destruction of the centres of worship. ‘Melt the figures of the gods and mint your coins with them; incorporate the votive offerings into the imperial treasury. The Lord has called you to higher undertakings, when you have crowned the task of annihilating all the temples’.

The spread of Christianity was the highest enterprise, along with the eradication of the pernicious pagan doctrines. Of course, adepts of the Greco-Roman world did not think so, but the other way around. ‘The opinion that, with the irruption of Christianity in the world, it had begun a general decline of the human species’ (Friedlander) was gaining strength.

Always invoking the Yahweh of the Old Testament, as is logical, until then no Christian had claimed with so much emphasis heir to the biblical hecatombs, nor had he used the precedent so systematically to justify resorting to brutality and terror. God threatens even the family and children of the children, ‘lest the cursed seed survive, and there be no trace of the heathen generations’.

As soon as the Church found itself in a position of strength, it stopped rejecting violence in order to exercise it ‘by all means’, as the theologian Carl Schneider says. The old apologetics that spoke of freedom of cults is displaced by libel and diatribe; the ideology of martyrdom and the exemplary lives of the martyrs no longer matters, it is the hour of persecuting fanaticism, of ‘the powerful calls to the crusade’ by a Firmicus ‘denigrating non-Christian religions like no other before him’ (Hoheisel).

The emperors, certainly, were the ones who had the means to apply coercion and violence. But they were also Christians and many proofs will not be necessary to suppose that the book of Firmicus Maternus, dedicated to the emperors Constantius and Constans, would not fail to influence in some measure the anti-pagan policy of them; their prohibitions and their threats. And these, in turn, would determine the position of the author of that Christian pamphlet.