Below, abridged translation from the first

volume of Karlheinz Deschner’s Kriminalgeschichte

des Christentums (Criminal History of Christianity)

First assaults on the temples

Paganism still had many followers among the peasants, the many rectors and philosophers; it was also preserved among the cultivated aristocracy, especially the most rancid senatorial families, even among those of the Eastern empire.

In the year 341, a decree attributed to Constans began not with the classic exposition of motives, but with a propagandistic cry: ‘Let the superstition cease! May the delirium of sacrifices be abolished!’ (caesat superstitio sacrificiorum aboleatur insania). Consequently, the sovereign ordered in 346 the closing, with immediate effects, of the temples located in the cities; in 356, the closing of all the temples was ordered.

The question was to prevent the wicked (perditi) from doing their bad things, which triggered a wave of assaults on the temples. The confiscation of property and death by stepping on a temple, or by participating in the ‘aberration’ of sacrifices or worshiping an image, was one of the points of the laws of Constantius: ‘Whoever such things do, be struck down by the avenger sword’.

Libanius, a pagan Hellene rector of Antioch, wrote that Constantius inherited from his father ‘the spark of the inclination to evil deeds, converted by him into a great fire, because he plunders the treasures of the gods, demolishes the temples, annuls the sacred canons’. Libanius comments that Constantius ‘generalized to the rhetoric (logoi) the contempt of pagan worship, and it is not surprising, because both, worship and rhetoric are related and go together’. The contemporary reader will understand that with this he accused the emperor of going against religion and against classical culture at the same time.

The most fanatical Christians already attacked altars and temples. The deacon Cyril of Heliopolis, for example, became famous with his actions. In Arethusa of Syria, the priest Marcus made to demolish an old sanctuary (what later, being bishop and during the reaction of Julian, it was worth a serious beating). In Caesarea of Cappadocia, the Christian community razed a temple of Zeus, patron of the city, and another of Apollo. In Alexandria, the Arian Georgios destroyed a whole series of sacred places of paganism.

Hecatombs under the pious Gallus

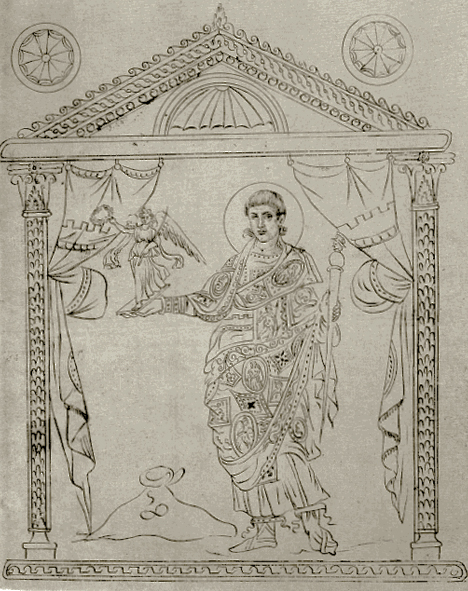

(Constantius Gallus in a late copy of 354.) In Palestine, the scene of the process of Scythopolis, occurred the outrages of Gallus, a cousin of Constantius who was saved from the dynastic slaughter of the year 337. We find here another good Christian, assiduous to the church since childhood, great reader of the Bible and supposedly faithful husband of the old Constantina, sister of the emperor and married in second nuptials: a notorious harpy, ‘an unleashed fury’, Amianus wrote, ‘as bloodthirsty as his own husband’.

(Constantius Gallus in a late copy of 354.) In Palestine, the scene of the process of Scythopolis, occurred the outrages of Gallus, a cousin of Constantius who was saved from the dynastic slaughter of the year 337. We find here another good Christian, assiduous to the church since childhood, great reader of the Bible and supposedly faithful husband of the old Constantina, sister of the emperor and married in second nuptials: a notorious harpy, ‘an unleashed fury’, Amianus wrote, ‘as bloodthirsty as his own husband’.

Gallus sent his brother Julian several letters of reprimand, inviting him to return to Christianity. In 351, the year of his proclamation as Caesar, Gallus scandalized the pagans by carrying the bones of Saint Babylas—incidentally, the first well-documented relocation we know—to the famous Apollo sanctuary in Daphne, which was thus rendered denaturalized.

The Christian Gallus, a great fan of boxing (at that time boxing was very bloody, with frequent breaking of bones), was revealed as a little tyrant in his residence of Antioch, through arbitrariness of all kinds and trials for high treason and witchcraft in which he made fun of all the legal norms and that brought a wake of confiscations, exile, horrible tortures and executions.

The fight against the pagans was tinged with true fanaticism, and he used a network of spies that covered the entire city. The Caesar Gallus, of whom Theodoret says with emphasis that ‘he was orthodox to death until the day of his death’, even induced some lynching by the plebs to get rid of certain uncomfortable fellow citizens. In 352, when the Jews suffered another of their periodic attacks of messianic excitement and rebelled against the prohibition of having slaves who were not Jews, assaulting a Roman garrison to procure weapons and naming someone of name Patrician, the pious Gallus burned entire cities and cut the throats even of the children.

Nor were the high imperial officials saved from this regime of terror; thus it fell the prefect of the East, Thalasius, directly responsible to the emperor. He was succeeded by Domitian, who shortly after his arrival in Antioch was captured by the soldiers, dragged through the streets, hung by his legs and thrown into the river Orontes; the same end suffered his quaestor.

There were several other murders, and towards the beginning of the summer of 354 the population rose ‘for varied and complicated reasons’, as Ammianus writes, but above all because of famine and general misery. Governor Theophilus was killed and dismembered.

Constantius was in need of calling his cousin, despite having promised him full immunity, and asked him to be accompanied by his wife, ‘the lovely Constantina’, since he had not seen her for a long time. Gallus understood that there was something fishy, but he trusted the support of Constantina, the emperor’s sister.

But this supporter died in those days as a result of a fever and the emperor beheaded his man of confidence one autumn morning in 354, in Istria. After the execution he proceeded with the rack, the axe of the executioner or exile against all the friends of Gallus, his officers and officials, and even against some religious people.

Only the death of the sovereign, at forty-four years of age on November 3, 361, avoided Constantius a confrontation with his cousin Julian.