Month: April 2023

Dominion, 19

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

Martin Luther, who as a monk

Martin Luther, who as a monk

had been notably scrawny,

ended up putting on so much

weight that he was denounced

by one adversary as a dainty

for the Devil.

The above image and accompanying text appears in colour in Tom Holland’s book.

Luther had come to believe that true reformatio would be impossible without consigning canons, papal decrees and Aquinas’ philosophy to the flames. Then, in the wake of his meeting with the cardinal, he had come to an even more subversive conclusion… Now, travelling to the diet, Luther was greeted with matching displays of exuberance. Welcoming committees toasted him at the gates of city after city; crowds crammed into churches to hear him preach. As he entered Worms, thousands thronged the streets to catch a glimpse of the man of the hour. [pages 316-317]

Luther didn’t approve of the historical humiliation that Gregory VII inflicted on Henry IV, which so empowered the papacy. It is worth mentioning here, using Savitri Devi’s philosophy, that unlike us Luther was ‘a man of his time’, as can be seen from the above passage. Discontent with Rome was already in the Germanic air when this obscure monk rebelled.

The founding claim of the order promoted by Gregory VII, that the clergy were an order of men radically distinct from the laity, was a swindle and a blasphemy. ‘A Christian man is a perfectly free lord of all, and subject to none.’ So Luther had declared a month before his excommunication, in a pamphlet that he had pointedly sent to the pope. ‘A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.’ The ceremonies of the Church could not redeem men and women from hell, for it was only God who possessed that power. A priest who laid claim to it by virtue of his celibacy was playing a confidence trick on both his congregation and himself. So lost were mortals to sin that nothing they did, no displays of charity, no mortifications of the flesh, no pilgrimages to gawp at relics, could possibly save them. Only divine love could do that. Salvation was not a reward. Salvation was a gift. [pages 317-318]

Once more: the schizophrenogenic (i.e., it drives you mad) doctrine of salvation from eternal torture thanks to the god of the Jews!

It was in the certitude of this that Luther, the day after his first appearance before Charles V, returned to the bishop’s palace. Asked again if he would renounce his writings, he said that he would not. As dusk thickened, and torches were lit in the crowded hall, Luther fixed his glittering black eyes on his interrogator and boldly scorned all the pretensions of popes and councils. Instead, so he declared, he was bound only by the understanding of scripture that had been revealed to him by the Spirit. ‘My conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience.’

Two days after listening to this bravura display of defiance, Charles V wrote a reply. Obedient to the example of his forebears, he vowed, he would always be a defender of the Catholic faith, ‘the sacred rituals, decrees, ordinances and holy customs’. He therefore had no hesitation in confirming Luther’s excommunication. Nevertheless, he was a man of his word. The promise of safe passage held. Luther was free to depart. He had three weeks to get back to Wittenberg. After that, he would be liable for ‘liquidation’. Luther, leaving Worms, did so as both a hero and an outlaw. The drama of it all, reported in pamphlets that flooded the empire, only compounded his celebrity. Then, halfway back to Wittenberg, another astonishing twist. Travelling in their wagon through Thuringia, Luther and his party were ambushed in a ravine. A posse of horsemen, pointing their crossbows at the travellers, abducted Luther and two of his companions. The fading hoofbeats left behind them nothing but dust. As to who might have taken Luther, and why, there was no clue. Months passed, and still no one seemed any the wiser. It was as though he had simply vanished into thin air.

All the while, though, Luther was in the Wartburg. The castle belonged to Friedrich, whose men had brought him there for safe-keeping. Disguised as a knight, with two servant boys to attend him, but no one to argue with, no one to address, he was miserable. The devil nagged him with temptations. Once, when a strange dog came padding into his room, Luther —who loved dogs dearly—identified it as a demon and threw it out of his tower window. [318-319]

So typical: Christians like to worship crazy and bad people instead of sane and good people. How can the white race not be in bad shape with gurus like Luther (just compare him with Hitler’s priestess)?

He suffered terribly from constipation. ‘Now I sit in pain like a woman in childbirth, ripped up, bloody.’ He did not, as Saint Elizabeth had done when she lived in the castle, welcome suffering. He had come to understand that he could never be saved by good works. It was in the Wartburg that Luther abandoned forever the disciplines of his life as a monk. Instead, he wrote. Lonely in his eyrie, he could look down at the town of Eisenach, where Hilten had prophesied the coming of a great reformer, and believe himself—despite his isolation from the mighty convulsions that he himself had set in train—to be the man foretold…

Now, with his translation, Luther had given Germans everywhere the chance to do the same. All the structures and the traditions of the Roman Church, its hierarchies, and its canons, and its philosophy, had served merely to render scripture an entrapped and feeble thing, much as lime might prevent a bird from taking wing. By liberating it, Luther had set Christians everywhere free to experience it as he had experienced it: as the means to hear God’s living voice. Opening their hearts to the Spirit, they would understand the true meaning of Christianity, just as he had come to understand it. There would be no need for discipline, no need for authority. Antichrist would be routed. All the Christian people at long last would be as one. [319-321]

When I finish this series I will resume the new translation of Hitler’s after-dinner talks. It is very good to have Savitri’s manifesto explaining National Socialism after the catastrophe of 1945. But we need the Führer’s own words to give us an accurate picture of NS.

I have said in the past that the only thing I disagreed with in those talks was Hitler’s position on Charlemagne. But as I recall, he once spoke of Luther without criticising him.

That position differs radically from Nietzsche’s, especially what he wrote in the final pages of The Antichrist. Remember: when an isolated Aryan comes to see through the thick darkness of two millennia, he suffers annihilation in his loneliness because the rest of the white men insist on remaining in darkness. I am closer to that poor alienated man, Nietzsche, when it comes to Luther than to Hitler and his beloved Wagner (the latter, baptised in a Lutheran church).

In short, Nietzsche is right to blame Luther and Germany for the darkness that would flood the post-Renaissance mind. According to the German philosopher, when visiting Rome Luther should have knelt in true grace, with tears in his eyes as he saw how Renaissance painting, sculpture and architecture hinted a coming transvaluation of all values! (something only Wagner, centuries later, would take up again with his pagan operas that we recently reviewed). But Luther did the opposite: he thrust into the Germanic soul not only the New Testament but now the Old Testament: the holy book of the Jews. See William Pierce’s critique of Luther in Who We Are, already quoted in a couple of ‘Our books’.

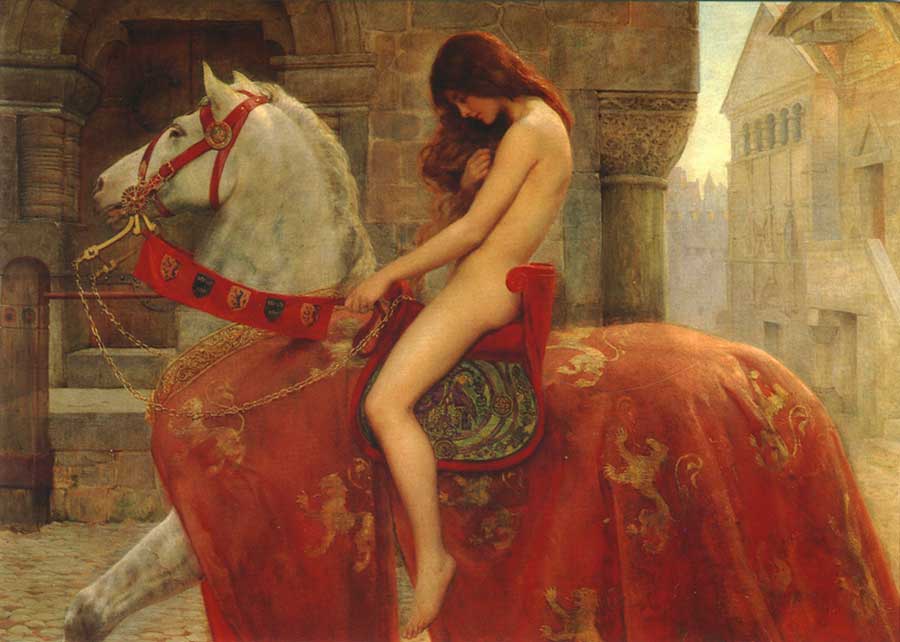

Lady Godiva

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

In 1516, any lingering hopes that Ferdinand might prove to be the last emperor were put to rest by his death. He had not led a great crusade to reconquer Jerusalem; Islam had not been destroyed. Nevertheless, the achievements of Ferdinand’s reign had been formidable. His grandson, Charles, succeeded to the rule of the most powerful kingdom in Christendom, and to a sway more authentically globe-spanning than that of the Caesars. Spaniards felt no sense of inferiority when they compared their swelling empire to Rome’s. Quite the contrary. From lands unknown to the ancients came news of feats that would have done credit to Alexander: the toppling against all the odds of mighty kingdoms; the winning of dazzling fortunes; men who had come from nowhere to live like kings.

Yet there lay over the brilliance of these achievements a pall of anxiety. No people in antiquity would ever have succeeded in winning an empire for themselves had they doubted their licence to slaughter and enslave the vanquished; but Christians could not so readily be innocent in their cruelty. When scholars in Europe sought to justify the Spanish conquest of the New World, they reached not for the Church Fathers, but for Aristotle. ‘As the Philosopher says, it is clear that some men are slaves by nature and others free by nature.’ Even in the Indies, though, there were Spaniards who worried whether this was truly so. ‘Tell me,’ a Dominican demanded of his fellow settlers, eight years before Cortés took the road to Tenochtitlan, ‘by what right or justice do you keep these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged a detestable war against these people, who dwelt quietly and peacefully in their own land?’

The Dominican Tom Holland alluded to above was Antonio de Montesinos, a Spanish missionary and friar. Together with the first community of Dominicans in the American continent, led by the vicar Fray Pedro de Córdoba, he distinguished himself in the defence of the Indians from the Spanish colonisers. He caused the conversion of Bartolomé de las Casas to the defence of the Indians, about whom I have written on this site more than one article.

When I considered myself a white nationalist and wrestled inwardly over which was the ultimate cause of Aryan decline, Judaism or Christianity, one of the factors that tipped the balance towards the latter was my father’s ideology. I wondered what caused him to go astray: the television he watched or his Catholic upbringing, which led to an exacerbated admiration for these Spanish friars. Eventually, I realised that it was the Christian religion that was the underlying factor in my father’s embrace of the Black Legend created by these friars.

Anyone interested in the details of this psychological analysis of my father and his admired friars can read El Grial. Holland continues:

Most of the friar’s congregation, too angered to reflect on his questions, contented themselves with issuing voluble complaints to the local governor, and agitating for his removal; but there were some colonists who did find their consciences pricked. Increasingly, adventurers in the New World had to reckon with condemnation of their exploits as cruelty, oppression, greed. Some, on occasion, might even come to this realisation themselves. The most dramatic example occurred in 1514, when a colonist in the West Indies had his life upended by a sudden, heart-stopping insight: that his enslavement of Indians was a mortal sin.

As always, the latent threat of eternal damnation is behind the great pathologies of the West.

Like Paul on the road to Damascus, like Augustine in the garden, Bartolomé de las Casas found himself born again. Freeing his slaves, he devoted himself from that moment on to defending the Indians from tyranny. Only the cause of bringing them to God, he argued, could possibly justify Spain’s rule of the New World; and only by means of persuasion might they legitimately be brought to God. ‘For they are our brothers, and Christ gave his life for them.’

Las Casas, whether on one side of the Atlantic, pleading his case at the royal court, or on the other, in straw-thatched colonial settlements, never doubted that his convictions derived from the mainstream of Christian teaching. [pages 307-308]

Dominion, 17

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

In 1453, Constantinople had finally fallen to the Turks. The great bulwark of Christendom had become the capital of a Muslim empire. The Ottomans, prompted by their conquest of the Second Rome to recall prophecies spoken by Muhammad, foretelling the fall to Islam of Rome itself, had pressed on westwards. In 1480, they had captured Otranto, on the heel of Italy. The news of it had prompted panic in papal circles—and not even the expulsion of the Turks the following year had entirely settled nerves. Terrible reports had emerged from Otranto: of how the city’s archbishop had been beheaded in his own cathedral, and some eight hundred others martyred for Christ.

Across Christendom, then, dread of what the future might hold continued to be joined with hope: of the dawning of a new age, when all of humanity would be gathered under the wings of the Spirit, that holy dove which, at Jesus’ baptism, had descended upon him from heaven. The same sense of standing on the edge of time that in Bohemia had led the Taborites to espouse communism elsewhere prompted Christians to anticipate that all the world would soon be brought to Christ. In Spain, where war against Muslim potentates had been a way of life for more than seven hundred years, this optimism was particularly strong. Men spoke of El Encubierto, the Hidden One: the last Christian emperor of all. At the end of time, he would emerge from concealment to unify the various kingdoms of Spain, to destroy Islam for good, to conquer Jerusalem, to subdue ‘brutal kings and bestial races’ everywhere, and to rule the world. [pages 301-302]

On the next page Holland continues:

Ferdinand was certainly free now to look to broader horizons. Among the cheering crowds watching the royal entry into Granada was a Genoese seafarer by the name of Christopher Columbus…

Three years later, during the course of a voyage blighted by storms, hostile natives and a year spent marooned on Jamaica, Columbus’ mission was confirmed for him directly by a voice from heaven. Speaking gently, it chided him for his despair, and hailed him as a new Moses. Just as the Promised Land had been granted to the Children of Israel, so had the New World been granted to Spain. Writing to Ferdinand and Isabella about this startling development, Columbus insisted reassuringly that it had all been prophesied by Joachim of Fiore. Not for nothing did his own name mean ‘the dove’, that emblem of the Holy Spirit. The news of Christ would be brought to the New World, and its treasure used to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem…

In 1519, more than a decade after Columbus’ death, a Spanish adventurer named Hernán Cortés disembarked with five hundred men on the shore of an immense landmass that was already coming to be called America. Informed that there lay inland the capital of a great empire, Cortés took the staggeringly bold decision to head for it. He and his men were stupefied by what they found: a fantastical vision of lakes and towering temples, radiating ‘flashes of light like quetzal plumes’, immensely vaster than any city in Spain. Canals bustled with canoes; flowers hung over the waterways. Tenochtitlan, wealthy and beautiful, was a monument to the formidable prowess of the conquerors who had built it: the Mexica… [pages 303-305]

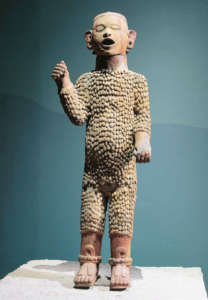

The bubbles on this statue represent lumpy fat

deposits of flayed human skin. Xipe Totec, worshipped

in central America as the Flayed One, appeared to

the Christian conquerors of the Mexica

not a god but a demon.

The above image and footnote text appears in Holland’s book. Just compare the art of these Amerindians with that of my last post in the ‘European beauty’ series! (Pallas Athena in the Austrian parliament).

Without sacrifice, so the Mexica believed, the gods would weaken, chaos descend, and the sun start to fade. Only chalchiuatl, the ‘precious water’ pumped out by a still-beating heart, could serve to feed it. Only blood, in the final reckoning, could prevent the universe from winding down.

To the Spaniards, the spectacle of dried gore on the steps of Tenochtitlan’s pyramids, of skulls grinning out from racks, was literally hellish. Once Cortés, in a feat of unparalleled audacity and aggression, had succeeded in making himself the master of the great city, its temples were razed to the ground. So Charlemagne, smashing with his mailed horsemen through dripping forests, had trampled down the shrines of Woden and Thunor. The Mexica, who had neither horses nor steel, let alone cannon, found themselves as powerless as the Saxons had once been to withstand Christian arms…

A decade before the conquest of Granada, Ferdinand had proclaimed it his intention ‘to dedicate Spain to the service of God’. In 1478, he had secured permission from the pope to establish, as the one institution common to both Aragon and Castile, an inquisition directly under royal control. 1492, the year of Granada’s fall and of Columbus’ first voyage, had witnessed another fateful step in the preparation of Spain for its mission to bring the gospel to the world. The Jews, whose conversion was destined to presage Christ’s return, had been given the choice of becoming Christian or going into exile. Many had opted to leave Spain; more, including the chief rabbi of Castile himself, had accepted baptism. [pages 305-306]

It was the National Socialists, not the Christians, who realised for the first time in history that this was a grave mistake: that the yardstick for discrimination is not faith but genes. But how many American racialist forums will pay homage to Uncle Adolf next week…?

Dominion, 16

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

One might think that the egalitarian follies of our time are a modern phenomenon. But militant, even very violent egalitarianism has ancient Christian roots.

The term Hussites or Hussite Church refers to a reform and revolutionary movement that arose in Bohemia in the 15th century. The name comes from the Bohemian theologian Jan Hus, who had been burnt in the stake. The movement later joined the Reformation.

A town was founded in 1420 by a group of the most radical wing of the Hussites, who gave it the biblical name of ‘Tabor’: the mountain where, according to the gospels, the transfiguration of Jesus took place. The members of this radical wing soon became known as Taborites and the word Tabor has come to mean in Czech ‘camp’.

The radical Hussites established a communal society in Tabor in which private property didn’t exist and any religious hierarchy was rejected. The egalitarian experiment lasted only one year, for in 1421 a moderate Hussite faction overran the Taborite fiefdom.

The town was rebuilt in the 16th century. In the chapter ‘Apocalypse, 1420: Tabor’ Tom Holland says:

The most popular preachers were those who condemned the wealth of monasteries adorned with gold and sumptuous tapestries, and demanded a return to the stern simplicity of the early days of the Church. The Christian people, they warned, had taken a desperately wrong turn. The reforms of Gregory VII, far from serving to redeem the Church, had set it instead upon a path to corruption. The papacy, seduced by the temptations of earthly glory, had forgotten that the Gospels spoke most loudly to the poor, to the humble, to the suffering. ‘The cross of Jesus Christ and the name of the crucified Jesus are now brought into disrepute and made as it were alien and void among Christians.’ Only Antichrist could have wrought such a fateful, such a hellish abomination. And so it was, in the streets of Prague, that it had become a common thing to paint the pope as the beast foretold by Saint John, and to show him wearing the papal crown, but with the feet of a monstrous bird. [page 295]

A couple of pages later Holland writes:

In the wake of Hus’ execution, denunciations of the papacy as Antichrist had begun to be made openly across Prague. Of Sigismund as well—for it was presumed that it was by his treachery that Hus had been delivered up to the flames…

The Taborites were hardly the first Christians to believe themselves living in the shadow of Apocalypse. The novelty lay rather in the scale of the crisis that had prompted their imaginings: one in which all the traditional underpinnings of society, all the established frameworks of authority, appeared fatally compromised. Confronted by a church that was the swollen body of Antichrist, and an emperor guilty of the most blatant treachery, the Taborites had pledged themselves to revolution. But it was not enough merely to return to the ideals of the early church: to live equally as brothers and sisters; to share everything in common. The filth of the world beyond Tabor, where those who had not fled to the mountains still wallowed in corruption, had to be swept away too. Its entire order was rotten. ‘All kings, princes and prelates of the church will cease to be.’ This manifesto, against the backdrop of Sigismund’s determination to break the Hussites, and the papacy’s declaration of a crusade against them, was one calculated to steel the Taborites for the looming struggle. Yet it was not only emperors and popes whom they aspired to eliminate. All those who had rejected the summons to Tabor, to redeem themselves from the fallen world, were sinners. ‘Each of the faithful ought to wash his hands in the blood of Christ’s foes.’

Many Hussites, confronted by this unsparing refusal to turn the other cheek, were appalled. ‘Heresy and tyrannical cruelty,’ one of them termed it. Others muttered darkly about a rebirth of Donatism. The summer of 1420, though, was no time for the moderates to be standing on their principles. The peril was too great. In May, at the head of a great army of crusaders summoned from across Christendom, Sigismund advanced on Prague. Ruin of the kind visited on Béziers two centuries earlier now directly threatened the city. Moderates and radicals alike accepted that they had no choice but to make common cause. The Taborites, leaving behind only a skeleton garrison, duly marched to the relief of Babylon. At their head rode a general of genius. Jan Žižka, one-eyed and sixty years old, was to prove the military saviour that the Albigensians had never found. That July, looking to break the besiegers’ attempt to starve Prague into submission, he launched a surprise attack so devastating that Sigismund was left with no choice but to withdraw. Further victories quickly followed. Žižka proved irresistible. Not even the loss late in 1421 of his remaining eye to an arrow served to handicap him. Crusaders, imperial garrisons, rival Hussite factions: he routed them all. Innovative and brutal in equal measure, Žižka was the living embodiment of the Taborite revolution. Noblemen on their chargers he met with rings of armoured wagons, hauled from muddy farmyards and manned by peasants equipped with muskets; monks he would order burnt at the stake, or else personally club to death. Never once did the grim old man meet with defeat. By 1424, when he finally fell sick and died, all of Bohemia had been brought under Taborite rule…

Readying Prague for their Lord’s arrival, they had systematically targeted symbols of privilege. Monasteries were levelled; the bushy moustaches much favoured by the Bohemian elite forcibly shaved off wherever they were spotted; the skull of a recently deceased king dug up and crowned with straw. As the months and then the years passed, however, and still Christ failed to appear, so the radicalism of the Taborites had begun to fade. They had elected a bishop; negotiated to secure a king; charged the most extreme in their ranks with heresy and expelled them from Tabor. Žižka, displaying a brusque lack of concern for legal process that no inquisitor would ever have contemplated emulating, had rounded up fifty of them and burnt the lot.[1] Well before the abrupt and crushing defeat of the Taborites by a force of more moderate Hussites in 1434, the flame of their movement had been guttering. Christ had not returned. The world had not been purged of kings. Tabor had not, after all, been crowned the New Jerusalem. In 1436, when Hussite ambassadors— achieving a startling first for a supposedly heretical sect—succeeded in negotiating a concordat directly with the papacy, the Taborites had little choice but to accept it. There would be time enough, at the end of days, to defy the order of the world. But until it came, until Christ returned in glory, what option was there except to compromise? [pages 297-300]

Jan Žižka is now a Czech national hero. Above, a statue by J. Strachovský, 1884 in his honor in the town square of Tabor, also called Žižka Square.

____________

[1] Only one man was spared, to provide an account of his sect’s beliefs.

Fire

‘Men like us need to devise our own mental tricks to not go nuts like Nietzsche. We carry the Sacred Fire, and we must be very careful who we show it to. In dissident circles this is called “hiding your power level”.’

Dominion, 15

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

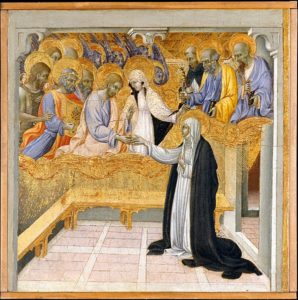

Giovanni di Paolo, The Mystic

Marriage of St Catherine of Siena.

On one occasion, when Christ appeared to Catherine of Siena, he did so accompanied by Mary Magdalene. Catherine, weeping with an excess of love, remembered how Mary, kneeling before the feet of her Lord, had once wet his feet with her own tears, and then wiped them with her hair, and kissed them, and anointed them with perfume. ‘Sweetest daughter,’ Christ told her, ‘for your comfort I give you Mary Magdalene for your mother.’ Gratefully, Catherine accepted the offer. ‘And from that moment on,’ so her confessor reported, ‘she felt entirely at one with the Magdalene.’

To be paired with the woman who had first beheld the risen Christ was, of course, a rare mark of divine favour. From childhood, Catherine had taken the Magdalene as a particular role model. Far from betraying complacency, though, this had borne witness to the opposite: Catherine’s own gnawing sense of sin. As reported by Luke, the woman who wept before Jesus, and anointed his feet, had ‘lived a sinful life’. Although she was never named, the identification of her with the Magdalene was one that had enjoyed wide currency ever since Gregory the Great, back in 591, had first made it in a sermon. Over time—and despite the lack of any actual evidence for it in the gospels—the precise character of her ‘sinful life’ had become part of the fabric of common knowledge. Kneeling before Jesus, seeking his forgiveness, she had done so as a penitent whore. Catherine, by accepting the Magdalene as her mother, was embracing the full startling radicalism of a warning given by Christ: that prostitutes would enter the kingdom of God before priests. [pages 285-286]

My book Daybreak (pages 132-135) contains an article with a splendid quote from Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose, where a wise Franciscan tells his pupil that the radicalism of St Francis was about empowering all sorts of ‘lepers’—the radical message of the gospel—as opposed to giving them simple alms. Those who haven’t read that article, which I entitled ‘On empowering carcass-eating birds’, should read it now. Using an article of The Occidental Observer it illuminates our understanding of how, in the secular phase of Christianity, the metastasis of gospel ethics has reached our day with the transgender movement: the new ‘leper’ to be empowered just as prostitutes would enter the Kingdom before priests! However, Christians, even medieval Christians, have always been contradicting themselves. Tom Holland continues:

In Paris, as the great cathedral of Notre Dame was being built, the offer from a collective of prostitutes to pay for one of its windows, and dedicate it to the Virgin, had been rejected by a committee of the university’s leading theologians. Two decades later, in 1213, one of the same scholars, following his appointment as papal legate, had ordered that all woman convicted of prostitution be expelled from the city—just as though they were lepers…

Yet always, lurking at the back of even the sternest preacher’s mind, was the example of Christ himself. In John’s gospel, it was recorded that a woman taken in adultery had been brought before him by the Pharisees. Looking to trap him, they had asked if, in accordance with the Law of Moses, she should be stoned. Jesus had responded by bending down and writing in the dust with his finger; but then, when the Pharisees persisted in questioning him, he had straightened up again. ‘If any of you is without sin, let him be the first to throw a stone at her.’ The crowd, shamed by these words, had hesitated—and then melted away. Finally, only the woman had been left. ‘Has no one condemned you?’ Jesus had asked. ‘No one, Sir,’ she had answered. ‘Then neither do I condemn you. Go now and leave your life of sin.’ [pages 286-287]

In the video I embedded on Thursday St Francis, dressed in rags, in front of the pope on his throne with the cardinals, bishops and abbots of the papal court, recites some of the words of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount praising ultimate poverty as a protest that the teachings of Christ are totally opposed to Rome’s obsession with wealth. The struggle between the purist monks that follow the gospel message and the more practical Roman curia has always existed. But it is something the American racial right is unwilling to acknowledge: obsessed as they are with blaming only contemporary Jewry for the subversion of the Church when the revolutionary message of the last being first came directly from the New Testament—a NT written by Jews!

Innocent III, that most formidable of heresy’s foes, never forgot that his Saviour had kept company with the lowest of the low: tax-collectors and whores. Endowing a hospital in Rome, he specified that it offer a refuge to sex-workers from walking the streets. To marry one, he preached, was a work of the sublimest piety… Prostitutes themselves, perfectly aware of the example offered them by the Magdalene, veered between tearful displays of repentance and the conviction that God loved them just as much as any other sinner. Catherine, certainly, whenever she met with a sex-worker, would never fail to assure her of Christ’s mercy. ‘Turn to the Virgin. She will lead you straight into the presence of her son.’