by Ron Unz

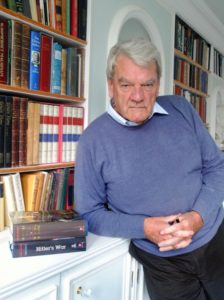

I’m very pleased to announce that our selection of HTML Books now contains works by renowned World War II historian David Irving, including his magisterial Hitler’s War, named by famed military historian Sir John Keegan as one of the most crucial volumes for properly understanding that conflict.

I’m very pleased to announce that our selection of HTML Books now contains works by renowned World War II historian David Irving, including his magisterial Hitler’s War, named by famed military historian Sir John Keegan as one of the most crucial volumes for properly understanding that conflict.

With many millions of his books in print, including a string of best-sellers translated into numerous languages, it’s quite possible that the eighty-year-old Irving today ranks as the most internationally-successful British historian of the last one hundred years. Although I myself have merely read a couple of his shorter works, I found these absolutely outstanding, with Irving regularly deploying his remarkable command of the primary source documentary evidence to totally demolish my naive History 101 understanding of major historical events. It would hardly surprise me if the huge corpus of his writings eventually constitutes a central pillar upon which future historians seek to comprehend the catastrophically bloody middle years of our hugely destructive twentieth century even after most of our other chroniclers of that era are long forgotten.

Carefully reading a thousand-page reconstruction of the German side of the Second World War is obviously a daunting undertaking, and his remaining thirty-odd books would probably add at least another 10,000 pages to that Herculean task. But fortunately, Irving is also a riveting speaker, and several of his extended lectures of recent decades are conveniently available on YouTube, as given below. [Editor's note: They have already been censored on YouTube, but can be viewed on BitChute.] These effectively present many of his most remarkable revelations concerning the wartime policies of both Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler, as well as sometimes recounting the challenging personal situation he himself faced. Watching these lectures (here and here) may consume several hours, but that is still a trivial investment compared to the many weeks it would take to digest the underlying books themselves.

When confronted with astonishing claims that completely overturn an established historical narrative, considerable skepticism is warranted, and my own lack of specialized expertise in World War II history left me especially cautious. The documents Irving unearths seemingly portray a Winston Churchill so radically different from that of my naive understanding as to be almost unrecognizable, and this naturally raised the question of whether I could credit the accuracy of Irving’s evidence and his interpretation. All his material is massively footnoted, referencing copious documents in numerous official archives, but how could I possibly muster the time or energy to verify them?

Rather ironically, an extremely unfortunate turn of events seems to have fully resolved that crucial question.

Irving is an individual of uncommonly strong scholarly integrity, and as such he is unable to see things in the record that do not exist, even if it were in his considerable interest to do so, nor to fabricate non-existent evidence. Therefore, his unwillingness to dissemble or pay lip-service to various widely-worshiped cultural totems eventually provoked an outpouring of vilification by a swarm of ideological fanatics drawn from a particular ethnic persuasion. This situation was rather similar to the troubles my old Harvard professor E.O. Wilson had experienced around that same time upon publication of his own masterwork Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, the book that helped launch the field of modern human evolutionary psychobiology.

These zealous ethnic-activists began a coordinated campaign to pressure Irving’s prestigious publishers into dropping his books, while also disrupting his frequent international speaking tours and even lobbying countries to bar him from entry. They maintained a drumbeat of media vilification, continually blackening his name and his research skills, even going so far as to denounce him as a “Nazi” and a “Hitler-lover,” just as had similarly been done in the case of Prof. Wilson.

During the 1980s and 1990s, these determined efforts, sometimes backed by considerable physical violence, increasingly bore fruit, and Irving’s career was severely impacted. He had once been feted by the world’s leading publishing houses and his books serialized and reviewed in Britain’s most august newspapers; now he gradually became a marginalized figure, almost a pariah, with enormous damage to his sources of income.

In 1993, Deborah Lipstadt, a rather ignorant and fanatic professor of Theology and Holocaust Studies (or perhaps “Holocaust Theology”) ferociously attacked him in her book as being a “Holocaust Denier,” leading Irving’s timorous publisher to suddenly cancel the contract for his major new historical volume. This development eventually sparked a rancorous lawsuit in 1998, which resulted in a celebrated 2000 libel trial held in British Court.

That legal battle was certainly a David-and-Goliath affair, with wealthy Jewish movie producers and corporate executives providing a huge war-chest of $13 million to Lipstadt’s side, allowing her to fund a veritable army of 40 researchers and legal experts, captained by one of Britain’s most successful Jewish divorce lawyers. By contrast, Irving, being an impecunious historian, was forced to defend himself without benefit of legal counsel.

In real life unlike in fable, the Goliaths of this world are almost invariably triumphant, and this case was no exception, with Irving being driven into personal bankruptcy, resulting in the loss of his fine central London home. But seen from the longer perspective of history, I think the victory of his tormenters was a remarkably Pyrrhic one.

Although the target of their unleashed hatred was Irving’s alleged “Holocaust denial,” as near as I can tell, that particular topic was almost entirely absent from all of Irving’s dozens of books, and exactly that very silence was what had provoked their spittle-flecked outrage. Therefore, lacking such a clear target, their lavishly-funded corps of researchers and fact-checkers instead spent a year or more apparently performing a line-by-line and footnote-by-footnote review of everything Irving had ever published, seeking to locate every single historical error that could possibly cast him in a bad professional light. With almost limitless money and manpower, they even utilized the process of legal discovery to subpoena and read the thousands of pages in his bound personal diaries and correspondence, thereby hoping to find some evidence of his “wicked thoughts.” Denial, a 2016 Hollywood film co-written by Lipstadt, may provide a reasonable outline of the sequence of events as seen from her perspective.

Yet despite such massive financial and human resources, they apparently came up almost entirely empty, at least if Lipstadt’s triumphalist 2005 book History on Trial may be credited. Across four decades of research and writing, which had produced numerous controversial historical claims of the most astonishing nature, they only managed to find a couple of dozen rather minor alleged errors of fact or interpretation, most of these ambiguous or disputed. And the worst they discovered after reading every page of the many linear meters of Irving’s personal diaries was that he had once composed a short “racially insensitive” ditty for his infant daughter, a trivial item which they naturally then trumpeted as proof that he was a “racist.” Thus, they seemingly admitted that Irving’s enormous corpus of historical texts was perhaps 99.9% accurate.

I think this silence of “the dog that didn’t bark” echoes with thunderclap volume. I’m not aware of any other academic scholar in the entire history of the world who has had all his decades of lifetime work subjected to such painstakingly exhaustive hostile scrutiny. And since Irving apparently passed that test with such flying colors, I think we can regard almost every astonishing claim in all of his books—as recapitulated in his videos—as absolutely accurate.

Aside from this important historical conclusion, I believe that the most recent coda to Irving’s tribulations tells us quite a lot about the true nature of “Western liberal democracy” so lavishly celebrated by our media pundits, and endlessly contrasted with the “totalitarian” or “authoritarian” characteristics of its ideological rivals, past and present.

In 2005, Irving took a quick visit to Austria, having been invited to speak before a group of Viennese university students. Shortly after his arrival, he was arrested at gunpoint by the local Political Police on charges connected with some historical remarks he had made 16 years earlier on a previous visit to that country, although those had apparently been considered innocuous at the time. Initially, his arrest was kept secret and he was held completely incommunicado; for his family back in Britain, he seemed to have disappeared off the face of the earth, and they feared him dead. More than six weeks were to pass before he was allowed to communicate with either his wife or a lawyer, though he managed to provide word of his situation earlier through an intermediary.

And at the age of 67 he was eventually brought to trial in a foreign courtroom under very difficult circumstances and given a three-year prison sentence. An interview he gave to the BBC about his legal predicament resulted in possible additional charges, potentially carrying a further twenty-year sentence, which probably would have ensured that he died behind bars. Only the extremely good fortune of a successful appeal, partly on technical grounds, allowed him to depart the prison grounds after spending more than 400 days under incarceration, almost entirely in solitary confinement, and he escaped back to Britain.

His sudden, unexpected disappearance had inflicted huge financial hardships upon his family, and they lost their home, with most of his personal possessions being sold or destroyed, including the enormous historical archives he had spent a lifetime accumulating. He later recounted this gripping story in Banged Up, a slim book published in 2008, as well as in a video interview available here.

Perhaps I am demonstrating my ignorance, but I am not aware of any similar case of a leading international scholar who suffered such a dire fate for quietly stating his historical opinions, even during in darkest days of Stalinist Russia or any of the other totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century. Although this astonishing situation taking place in a West European democracy of the “Free World” did receive considerable media exposure within Europe, coverage in our own country was so minimal that I doubt that today even one well-educated American in twenty is even aware it ever happened.

‘“Wahhh, you support genocide, you’re anti-White and bad” said the WN [white nationalist] fag pussy. Whites won’t survive if they don’t genocide non-Whites!’ —Twitter post

‘“Wahhh, you support genocide, you’re anti-White and bad” said the WN [white nationalist] fag pussy. Whites won’t survive if they don’t genocide non-Whites!’ —Twitter post