Or:

How the Woke monster originated

Before quoting the book, we should recall the pride shown in the Greco-Roman world for the Aryan nude in the form of public statuary, something that both Jews and Christians abhorred. The so-called Catholic saints only show a monstrous reversal of these values, as can be seen in the hagiographies rephrased by Tom Holland in his chapter ‘Persecution: 1229 Marburg’:

The Lady Elizabeth had been born to greatness. Descended from a cousin of Stephen, Hungary’s first truly Christian king, she had been sent as a child to the court of Thuringia, in central Germany, and groomed there for marriage. At the age of fourteen, she had joined Louis, its twenty-year-old ruler, on the throne. The couple had been very happy. Elizabeth had borne her husband three children; Louis had gloried in his wife’s demonstrable closeness to God. Even when he was woken in the night by a maid tugging on his foot, he had borne it patiently, knowing that the servant had mistaken him for his wife, whose custom it was to get up in the early hours to pray. Elizabeth’s insistence on giving away her jewellery to the poor; her mopping up of mucus and saliva from the faces of the sick; her making of shrouds for paupers out of her finest linen veils: here were gestures that had prefigured her far more spectacular self-abasement in the wake of her husband’s death. Her only regret was that it did not go far enough. ‘If there were a life that was more despised, I would choose it.’ When Count Paviam urged Elizabeth to abandon the rigours and humiliations of her existence in Marburg, and return with him to her father’s court, she refused point blank…

Clerks in the service of the papal bureaucracy and scholars learned in canon law had long been toiling to strengthen the foundations of the Church’s authority. They understood the awful responsibility that weighed upon their shoulders. Their task was to bring the Christian people to God. ‘There is one Catholic Church of the faithful, and outside of it there is absolutely no salvation.’ So it had been formally declared during Elizabeth’s childhood, in 1215, at the fourth of a series of councils convened at the Lateran. To defy this canon, to reject the structures of authority that served to uphold it, to disobey the clergy whose solemn prerogative it was to shepherd souls, was to follow the path to hell. [pages 247-249]

One thing that is completely absent on the intellectual right today is the historical memory of what the doctrine of eternal damnation meant for the mental health of medieval Europeans. I touched on the subject in my books on family tragedy; and more succinctly in ‘On Erasmus’, collected in one of the books of the featured post.

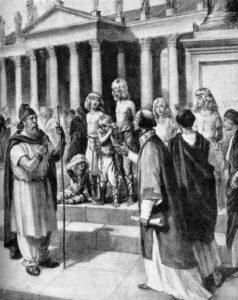

In 1206, a one-time playboy by the name of Francis, a native of the Italian city of Assisi, had spectacularly renounced his patrimony. Taking off his clothes, he had handed them over to his father. ‘Moreover he did not even keep his drawers, but stripped himself naked before all the bystanders.’ The local bishop, impressed rather than appalled by this display, had tenderly covered him with his own cloak, and sent him on his way with a blessing. Here, with this episode, had been set the pattern of Francis’ career. His genius for taking Christ’s teachings literally, for dramatising their paradoxes and complexities, for combining simplicity and profundity in a single memorable gesture, would never leave him. [page 251]

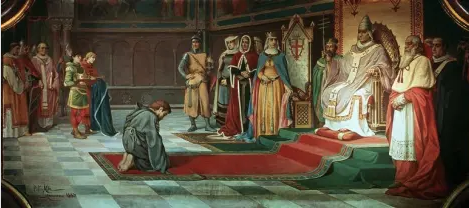

Above, St Francis’ renunciation of worldy goods by Giotto.

He served lepers; preached to birds; rescued lambs from butchers. Rare were those immune to his charisma. Admiration for his mission reached to the very summit of the Church. Innocent III, the pope who in 1215 had convened the Fourth Lateran Council, was not a man easily impressed. Imperious, daring and brilliant, he gave way to no one, overthrowing emperors, excommunicating kings. Unsurprisingly, then, when Francis, at the head of twelve ragged ‘brothers’, or ‘friars’, first arrived in Rome, Innocent had refused to see him. The whiff of heresy, not to mention blasphemy, had seemed altogether too rank. Francis, though, unlike Waldes, never stinted in his respect for the Church, in his obedience to its authority. Innocent’s doubts were eased. Imaginative as well as domineering, he had come to see in Francis and his followers not a danger, but an opportunity. Rather than treating them as his predecessors had treated the Waldensians, he ordained them a legally constituted order of the Church. ‘Go, and the Lord be with you, brethren, and as He shall deign to inspire you, preach repentance to all.’ [pages 251-252]

By 1217, less than a decade after this proclamation, a Franciscan mission had reached Germany. Elizabeth would grow up profoundly inspired by its example. By dressing in secret as a beggar, she had been paying tribute to Francis. Other demonstrations of her enthusiasm for his teachings were more public. In 1225, she provided the Franciscans with a base at the foot of the Wartburg, in the town of Eisenach. Three years later, following the death of her husband, she made her way there and formally renounced her ties to the world. Yet no matter how desperately she longed to do so, she did not then go begging from door to door. Elizabeth had properly absorbed the lessons of Francis’ example. She understood that to embrace poverty without obedience was to risk the fate of Waldes. [page-252]

While Waldes was very similar to Elizabeth and Francis in terms of mortifications of the flesh (which today would be considered a mental disorder, self-harm), in the eyes of the Church he was reprehensible because, unlike Elizabeth and Francis, he didn’t faithfully obey his ecclesiastical superiors: enough for him to be considered a heretic.

No mortification, no gesture of abasement, could possibly be undertaken unless at the command of a superior. Here, for a princess, the mistress of many servants, was a realisation that was itself a form of submission. So Elizabeth, even as she sat enthroned by her husband’s side, had employed a magister disciplinae spiritualis: a ‘master of spiritual discipline’. Not just any master, either. ‘I could have sworn obedience to a bishop or an abbot who had possessions, but I thought it better to swear obedience to one who has nothing and relies totally on begging. And so I submitted to Master Conrad’…

Even before Louis’ death, he had punished her for missing one of his sermons with a beating so violent that the stripes were still visible three weeks later… To suffer was to gain redemption. In 1231, when Elizabeth died of her austerities at the tender age of twenty-four, Conrad did not hesitate to hail her as a saint. As gold is purified by fire, so had she been purged of sin. The same strictness that had brought her to an early grave had brought her to heaven. [pages 252-253]

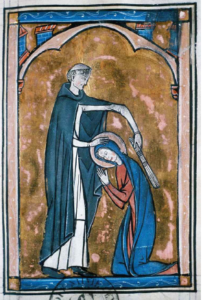

Elizabeth of Hungary submits to her master of spiritual discipline. This image appears in Holland’s book. Conrad was tireless in his defence of the Church and its authority:

In 1231, there came a fresh refinement. A new pope, Gregory IX, authorised Conrad not merely to preach against heresy, but to devote himself to the search for it—the inquisitio. No longer was it the responsibility of a bishop to bring heretics to trial, and sit in judgement on them, but rather that of a cleric especially appointed to the task. Even though, as a priest, Conrad could not himself ‘decree or pronounce a sentence involving the shedding of blood’, he was licensed by Gregory to compel the secular authorities to impose it. Never before had power of this order been given to a campaigner against heresy. Now, when Conrad rode on his mule from village to village, summoning the locals to answer his interrogation of their beliefs, he did so not merely as a preacher, but as a whole new breed of official: an inquisitor.

‘In all things he broke her will, to ensure that the merit of her obedience to him would increase.’ So Conrad had justified his handling of Elizabeth. Now, with all of Germany his to discipline, he could not afford to soften. The truest kindness was cruelty; the truest mercy harshness. The swarm of heretics that confronted Conrad were not readily to be redeemed from damnation. Only fire could smoke them out. Pyres needed to be stoked as they had never been stoked before. The burning of heretics—hitherto a rare and sporadic expedient, only ever reluctantly licensed, if at all—was the very mark of Conrad’s inquisition. In towns and villages along the Rhine, the stench of blackened flesh hung in the air. ‘So many heretics were burned throughout Germany that their number could not be comprehended.’ Conrad’s critics, unsurprisingly, accused him of a killing spree. They charged him with believing every accusation that was brought before him; of rushing the process of law; of sentencing the innocent to the flames. No one, though, was innocent. All were fallen. Better to suffer as Christ had suffered, tortured in a place of public execution for a crime that he had not committed, than to suffer eternal damnation. Better to suffer for a few fleeting moments than to burn for all eternity.

With Master Conrad, the yearning to cleanse the world of sin, to heal it of its leprosy, had turned murderous. That made it no less revolutionary. The suspicion of the worldly order that had brought Gregory VII to humble an anointed king before the gates of Canossa was one that Conrad more than shared. As Elizabeth’s master, he had forbidden her to eat food ‘about which she did not have a clear conscience’. Anything on her husband’s table that might have derived from exploitation of the poor, that might have been extracted from peasants as a tribute or a tax, she had dutifully spurned. ‘As a result, she often suffered great penury, eating nothing but rolls spread with honey.’ The Lady Elizabeth had been a saint. Her peers were not. In the summer of 1233, Conrad dared to accuse one of them, the Count of Sayn, of heresy. A frantically convened synod of bishops, in the presence of the German king himself, threw out the case. Conrad, nothing daunted, began to prepare charges against further noblemen.

Then, on 30 July, as he was returning from the Rhine to Marburg, he was ambushed by a group of knights and cut down. The news of his death was greeted with rejoicing throughout Germany. In the Lateran, though, there was indignation. As Conrad was laid to rest in Marburg, by the side of the Lady Elizabeth, Gregory mourned him in sombre terms. The murderers, so the Pope warned, were harbingers of a rising darkness. All of heaven and earth had shuddered at their crime. Their patron was literally hellish: none other than the Devil himself. [pages 254-256]