Or:

How the Woke monster originated

Tom Holland titles the next section of his book ‘Christendom’ (the previous section, ‘Antiquity’). The first chapter of this second section (‘Conversion: 754’) opens with vignettes from the life of a so-called saint:

As dawn broke, the camp on the banks of the river Boorne was already stirring. Boniface, its leader, was almost eighty, but as tireless as he had ever been. Forty years after his first journey to Frisia, he had returned there, in the hope of reaping from its lonely mudflats and marshes a great harvest of souls. Missionary work had long been his life. Born in Devon, in the Saxon kingdom of Wessex, he viewed the pagans across the northern sea as his kinsmen. In letters home he had regularly solicited prayers for their conversion. ‘Take pity upon them; for they themselves are saying: “We are of one blood and bone with you.”’ Now, after weeks of touring the scattered homesteads of Frisia, Boniface had summoned all those won for Christ to be confirmed in their baptismal vows. It promised him a day of joy.

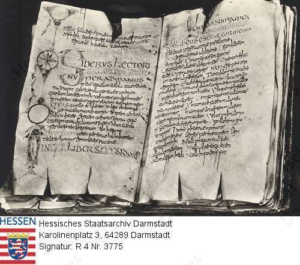

The first boats arrived as sunlight was starting to pierce the early morning cloud. A mass of men, after clambering onto dry land, walked up from the river and approached the camp. Then, abruptly, the glint of swords. A charge. Screams. Boniface came out of his tent. Already it was too late. The pirates were in the camp. Desperately, Boniface’s attendants fought back. Not the old man himself, though. Christ, when he was arrested, had ordered Peter to put up his sword; and now Boniface, following his Lord’s example, commanded his followers to lay down their weapons. A tall man, he gathered his fellow priests around him, and urged them to be thankful for the hour of their release. Felled by a pirate’s sword, he was cut to pieces. So violently did the blows rain down that twice a book he had in his hands was hacked through. Found long afterwards at the scene of his murder, it would be treasured ever after as a witness to his martyrdom. [pages 201-202]

The book which Saint Boniface, the ‘Apostle of the Germans’, reputedly held up to defend himself from the swords of the Frisians who killed him (Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt). This image appears in Holland’s book.

It was not the inheritance of Roman imperialism that inspired them, but the example of Patrick and Columbanus. To experience hardship was the very point. Fearsome stories were told of what missionaries might face. Woden [Wotan], king of the demons worshipped by the Germans as gods, was darkly rumoured to demand a tithe of human lives. [page 203]

Let’s compare this demonised vision of Wotan with the Wotan we just saw in the Wagnerian tetralogy (and let’s remember that for the Christians who destroyed the statues of Apollo and other Greco-Roman gods, they also said they were ‘demons’).

In the Low Countries, prisoners were drowned beneath rising tides; in Saxony, hung from trees, and run through with spears. Runes were dyed in Christian blood. Or so it was reported. Such rumours, far from intimidating Anglo-Saxon monks, only confirmed them in their sense of purpose: to banish the rule of demons from lands that properly belonged to Christ.

As vividly as anyone, they understood what it was to be born again. ‘The old has gone, the new has come!’ The tone of revolution in Paul’s cry, the sense that an entire order had been judged and found wanting, still retained a freshness for men like Boniface in a way that it did not in more venerable reaches of the Christian world. [page 203]

In the following pages Holland talks about something we have already seen in our translation of Deschner’s books: the felling of the sacred tree of the Saxons (here). He added:

To banish the past, to overturn custom: here was a fearsome project, barely comprehensible to the peoples of other places, other times… Barely a decade after Boniface’s arrival in the Low Countries, missionaries had begun to calculate dates in the manner of Bede: anno Domini, in the year of their Lord. The old order, which to pagans had seemed eternal, could now more firmly be put where it properly belonged: in the distant reaches of a Christian calendar. While the figure of Woden bestowed far too much prestige on kings ever to be erased altogether from their lineages, monks did not hesitate to demote him from his divine status and confine him to the remote beginnings of things. The rhythms of life and death, and of the cycle of the year, proved no less adaptable to the purposes of the Anglo-Saxon Church. So it was that hel, the pagan underworld, where all the dead were believed to dwell, became, in the writings of monks, the abode of the damned; and so it was too that Eostre, the festival of the spring, which Bede had speculated might derive from a goddess, gave its name to the holiest Christian feast-day of all. Hell and Easter: the garbing of the Church’s teachings in Anglo-Saxon robes did not signal a surrender to the pagan past, but rather its rout. Only because the gods had been toppled from their thrones, melted utterly by the light of Christ, or else banished to where monsters stalked, in fens or on lonely hills, could their allure safely be put to Christian ends. The victory of the new was adorned with the trophies of the old. [page 204]

The old incarnation of this site featured a Weirwood tree, straight out of the novels of George R.R. Martin, as the symbol of The West’s Darkest Hour (scroll down to the very bottom of e.g. this PDF). Since the theme of this new incarnation doesn’t allow displaying images in a sidebar, the Weirwood image no longer appears. However, in my mind it is still the symbol of this site, and I would like to explain why.

As past visitors know, I began my literary career by writing several books about the tragedy in my family. Unlike other victims who have already died because of such tragedy—my sister and two of my first cousins—I realised that only by telling myself the deep past could I heal.

That meant delving into our biographical past with the work equivalent of several doctorates, and the result was my series From Jesus to Hitler. But once I developed the gift of seeing the family past in a very different way than the family normies see it—with all their denials and repressions—, I realised that I could use that ‘gift’ to begin to see the authentic past of the West.

That’s why Martin’s fiction about the Weirwood trees appealed to me so much. If a greenseer touched them, he could paranormally see into Westeros’s past (what parapsychologists call retrocognition). It struck me greatly that I used to touch the trunk of the big tree in our backyard the way, in the television version of Martin’s books, Bran the Broken touched the Weirwood trees—but I did that decades before Martin began his novels.

The difference, of course, is that in the real world retrocognition probably doesn’t exist, and as a kid I didn’t see the past paranormally. But I touched the tree just as Bran would do decades later on an HBO series, and as a teenager I sensed that there was something numinous about it.

In order not to make this autobiographical vignette too long, the tree symbolises seeing the past as it happened, not as the normies believe it happened. That’s why Goodrich’s book is first on my list in ‘Our Books’. And the second book shows us the true history of Greece, Rome and how the Judeo-Christians ended that culture. (After all, the books that saved me were made from material taken from trees.)

Touching the Weirwood tree is what saves us, as long as the person touching it is a greenseer. For this reason, both Boniface and the invaders in Martin’s prose, the first thing they did was cut down the sacred trees. Holland ends that section with the following paragraphs:

As well as the Pope, he [Boniface] had won the backing of Charles Martel. The Frankish warlord, no less keen to break the eastern marches to his own purposes than the Anglo-Saxon bishop, had found in Boniface a man after his own heart. Tortured though Boniface was by the need to curry favour at court, and by his frustrated yearning to save the souls of pagans, he had succeeded, by the end of his life, in shaping the churches east of the Rhine to something like his own image. Returning, in the last year of his life, to the mission that had always been closest to his heart, he had done so as the dominant figure in the Frankish church…

Yet even as Boniface was being cut down amid the reeds and mud of Frisia, the lead given by missionaries in the spread of Christianity eastwards was passing. A new and altogether more militant approach to paganism was being prepared. The willingness of Boniface to meet death rather than permit his attendants to draw their swords was not one that the Frankish authorities tended to share. Three days after his murder, a squad of Christian warriors tracked down the killers, cornered them and wiped them out. Their women and children were taken as slaves. [pages 206-207]

3 replies on “Dominion, 7”

This is all profound and deep, but there’s an argument to be made that it was precisely the people living in those times who failed to appreciate the significance of the events transpired. Many Germanics did not understand the travesty of accepting the god of the Jews as theirs – especially considering how the early Bible translations were Nordicised (see the Heiland) – just as many in Europe would later miss the point of Hitlerianism. Ironically, it is with the height of the ages that correspondent hatred may be invoked.

(And regarding your old point, from Clarke’s Childhood End, about showing Christians via a magical Palantír-esque TV that Jesus never existed – that’s not how religious belief works. Normies merely obey the commands of a dominant culture.)

True: If Karellen came with his machines to see the past, the Christians would simply say that it is the devil who wants to mislead them with his deceitful magic. But in the novel, it is assumed that after half a century with these machines the new generations were no longer under the influence of Abrahamic religions.

In recent years I have abandoned Clarke’s fiction because it implied ET agency, and now I believe that eschatology must arise ‘from below’ (the Earth, trees, the ancient spirit of communion with Nature), not ‘from above’.

It is because the pagan world was too tolerant and passive to properly deal with Judeo Christianity.

The slave religion is like necrosis. It grows on death tissue after trauma (judaized aryans) and can spread to the rest of the body if you are too tolerant and do not amputate the infected part.

This is what ancient pagans failed to understand.