An abridged translation of the final chapter of Who We Are by William Pierce is now available in German.

Wer wir sind

Der folgende Text ist die Übersetzung einer Kurzfassung von „The Race’s Gravest Crisis Is at Hand“, dem Schlußkapitel von William Pierce’ Geschichte der weißen Rasse, „Who We Are“, ursprünglich erschienen in National Vanguard (Mai 1978 bis Mai 1982):

Seit dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs haben sich die Lage und die Aussichten der Weißen Rasse sowohl moralisch als auch materiell verschlechtert.

Seit dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs haben sich die Lage und die Aussichten der Weißen Rasse sowohl moralisch als auch materiell verschlechtert.

So schlecht der moralische Zustand der Rasse vor dem Krieg war, so unermesslich schlechter wurde er danach. Seit dem Dreißigjährigen Krieg hatten die Weißen einander nicht mehr mit einer solchen religiös motivierten Grausamkeit und in einem solchen Ausmaß umgebracht. Doch dieses Mal war der Aberglaube, mit dem all das Töten gerechtfertigt wurde, nicht so tief verwurzelt wie 300 Jahre zuvor.

Als die von Bombern gesäten Feuerstürme, die Hunderttausende von deutschen Frauen und Kindern in Dresden, Hamburg und einem Dutzend anderer Städte verbrannt hatten, sich ausgetobt hatten; als die letzte Massenerschießung von Kriegsgefangenen durch die Amerikaner vorüber war; als die Briten damit fertig waren, Hunderttausende von antikommunistischen Kroaten und Kosaken mit vorgehaltenem Bajonett an ihre kommunistischen Henker in Jugoslawien und der Sowjetunion auszuliefern; als die umherziehenden Vergewaltigerbanden im sowjetisch besetzten Berlin endlich gesättigt waren; als die Mordorgien in Paris und Prag und den anderen Hauptstädten des „befreiten“ Europas abgeklungen waren; als der Krieg und seine unmittelbaren, blutigen Nachwirkungen vorbei waren und die Weißen in Amerika und Großbritannien Gelegenheit hatten, ihr Werk zu begutachten und darüber nachzudenken, kamen die ersten Zweifel.

Einer der Hauptverantwortlichen für die Katastrophe, der britische Premierminister Winston Churchill, brachte diese Zweifel unverblümter und prägnanter als alle anderen zum Ausdruck. Als er in einem seiner seltenen Momente der Nüchternheit über die problematische Zukunft Großbritanniens in einem Nachkriegseuropa nachdachte, das von dem neu entstandenen sowjetischen Koloss überschattet wurde, platzte er heraus: „Wir haben das falsche Schwein geschlachtet.“ Dies war derselbe Churchill, der einige Monate zuvor in einem weniger nüchternen Moment seine Verachtung für das besiegte Deutschland dadurch symbolisch zum Ausdruck gebracht hatte, dass er in Anwesenheit einer Gruppe von Journalisten ostentativ in den Rhein urinierte.

Viele der westlichen Staats- und Regierungschefs, die in den Krieg verwickelt waren, hatten nicht mehr moralische Gewissensbisse oder Verantwortungsgefühl für das, was sie getan hatten, als Churchill. Ihr Geschrei über „deutsche Kriegsverbrechen“ war oft das wirksamste Mittel, um von ihren eigenen Verbrechen und den Verbrechen anderer abzulenken.

Die Einzelheiten der Geschichte der Nachkriegszeit waren in Großbritannien, Amerika, Frankreich und den anderen westlichen Nationen unterschiedlich, aber die allgemeinen Trends waren überall gleich. Die folgenden Abschnitte beziehen sich speziell auf die Vereinigten Staaten, aber die Schlussfolgerungen, zu denen sie führen, gelten für den Westen im Allgemeinen.

* * *

Bürgerrechte. Und dann, bevor irgendjemand sein Gleichgewicht finden und herausfinden konnte, was es bedeutet und wohin es führen würde, brach das Phänomen der „Bürgerrechte“ über das Nachkriegsamerika herein. Was vor dem Krieg unmöglich gewesen wäre, nahm in den späten 1940er Jahren Fahrt auf und zog in den folgenden zwei Jahrzehnten alle mit sich. Als sich der Rauch in den späten 1960er Jahren zu lichten begann, stellten die weißen Amerikaner fest, dass sie sich selbst um ihr kostbarstes und grundlegendes Bürgerrecht betrogen hatten: das Recht auf freie Vereinigung.

Sie konnten sich ihre Nachbarn nicht mehr aussuchen und vernünftige Maßnahmen ergreifen, um sicherzustellen, dass sich die rassische Zusammensetzung der Gemeinden, in denen sie lebten, nicht verschlechterte; jeder Versuch, dies zu tun, war illegal geworden und wurde mit einer Haftstrafe in einem Bundesgefängnis geahndet.

Sie konnten ihre Kinder nicht mehr in Schulen schicken, die sie mit ihren eigenen Steuern finanzierten und die von Kindern ihrer eigenen Rasse besucht wurden.

Diejenigen von ihnen, die Arbeitgeber waren, konnten keine Männer und Frauen ihrer Wahl mehr einstellen.

Jeder Ort und jede soziale Gruppierung, in der die weißen Männer und Frauen Amerikas frei mit ihresgleichen verkehren konnten – Wohnviertel und Arbeitsplätze, Schulen und Erholungsgebiete, Restaurants und Kinos, Militäreinheiten und städtische Polizeikräfte –, stand nun auch Nicht-Weißen offen, und letztere zögerten nicht lange und verschafften sich dort einen Stand.

Multirassische Pseudo-Nation. Was in der erstaunlich kurzen Zeit von etwas mehr als zwei Jahrzehnten erreicht worden war, war die Umwandlung des stärksten, reichsten und fortschrittlichsten Landes der Erde von einer Weißen Nation, in der rassische Minderheitengruppen von jeder nennenswerten Teilhabe an der Weißen Gesellschaft – außer als Arbeitskräfte – faktisch ausgeschlossen waren, in eine multirassische Pseudonation, in der Nichtweiße nicht nur teilnahmen, sondern eine privilegierte und verwöhnte Elite bildeten.

Das Ausmaß der Transformation ist vielen Weißen, die nach ihrem Beginn geboren wurden, nicht bewusst, aber es lässt sich leicht nachvollziehen, wenn man sich die kulturellen Zeugnisse der früheren Ära ansieht. Ein Vergleich von Zeitschriftenanzeigen oder fotografierten Straßenszenen, von populärer Belletristik oder Grundschullehrbüchern, von Kinofilmen oder Gesichtern in Highschool-Jahrbüchern von 1940 mit denen des letzten Jahrzehnts zeigt die Geschichte in aller Deutlichkeit.

Diese radikale Enteignung weißer Amerikaner wurde nicht nur im Namen von „Gerechtigkeit“ und „Freiheit“ durchgeführt, sondern es wurde dabei auch kaum ein Schuss abgegeben: Insgesamt fielen nicht mehr als ein Dutzend Weiße bei dem schwachen und völlig wirkungslosen Widerstand, der dagegen geleistet wurde. Mehr als alles andere zeigt dieser Mangel an Widerstand den moralischen Zustand der Rasse in der Nachkriegszeit.

Es stimmt natürlich, dass die Juden, die die Enteignung planten und einen großen Anteil daran hatten, sich gut vorbereitet hatten. Wenige Jahre vor dem Krieg befanden sich noch große Teile der amerikanischen Nachrichten- und Unterhaltungsmedien in den Händen von rassisch bewussten Weißen. Große Verlage veröffentlichten in den 1920er und 1930er Jahren Bücher, die sich offen mit Eugenik, Rassenunterschieden und dem Judenproblem auseinandersetzten. Henry Ford, Amerikas führender Industrieller, schenkte in den 1920er Jahren den Käufern seiner Automobile eine Zeit lang ein Freiexemplar von The International Jew, einem stark antijüdischen Buch, das zuvor in seiner Zeitung The Dearborn Independent erschienen war.

In den 1930er Jahren sprach sich Pater Charles Coughlan, ein unabhängiger katholischer Priester mit einer Radiosendung, die von Millionen gehört wurde, entschieden gegen jüdische politische Intrigen aus, bis er durch eine Anordnung des Vatikans zum Schweigen gebracht wurde.

Doch gegen Ende des Krieges hatten die Juden die Medien so fest im Griff, dass abweichende Meinungen gegen ihre Politik in der Öffentlichkeit kein Gehör fanden. Keine große Zeitung, keine Filmgesellschaft, kein Radiosender und keine populäre Zeitschrift war mehr in den Händen ihrer Gegner.

Einige Institutionen, vor allem die christlichen Kirchen, trugen die Saat der Rassenvernichtung bereits in sich und brauchten relativ wenig Aufwand, um sie mit den jüdischen Plänen in Einklang zu bringen. Andere (die Ford Foundation ist ein eindrucksvolles Beispiel) wurden infiltriert, übernommen und in eine Richtung gelenkt, die der von ihren Gründern beabsichtigten diametral entgegengesetzt war.

Eine tiefgehende moralische Krankheit. Letztlich ändert jedoch nichts von alledem etwas an der Tatsache, dass die weiße Bevölkerung der westlichen Nationen in der Nachkriegszeit moralisch zutiefst krank ist. Es handelt sich um eine Krankheit, die tief in der Vergangenheit wurzelt, wie in früheren Beiträgen dargelegt wurde, aber im Amerika der Nachkriegszeit zur Blüte gelangte.

Es ist schwierig, das Hexengebräu zu analysieren und den einzelnen Zutaten genau die Schuld zuzuweisen. Es gab zum einen den Trend zu einer immer vulgäreren und unehrlicheren Demokratie, der schon lange vor dem Krieg einsetzte und mit dem Eintritt Franklin Roosevelts auf die nationale politische Bühne im Jahr 1932 einen neuen Höhepunkt erreichte.

Und es gab den Verlust der Verwurzelung und die damit einhergehende zunehmende Entfremdung, die sich aus der größeren Mobilität der motorisierten Bevölkerung ergab.

Schlussendlich war da das mächtige neue Propagandamedium Fernsehen mit seiner beängstigenden Fähigkeit, zu hypnotisieren und zu manipulieren.

Aber es war das unsagbar grausame Verbrechen des Krieges selbst und seine Auswirkungen auf diejenigen, die an ihm teilnahmen, das als Katalysator diente, der alle Elemente miteinander reagieren ließ und die Krankheit selbst metastasierte.

Der böse Geist der unmittelbaren Nachkriegszeit war damals nur für einige wenige besonders fühlsame Menschen erkennbar, während die meisten nicht unter den oberflächlichen Glitter von Veränderung und Bewegung sehen konnten.

Die gegenwärtige Bedrohung für das Überleben der Weißen Rasse ist sowohl physisch als auch moralisch: Während sich das zahlenmäßige Gleichgewicht der Rassen sowohl in der Welt als Ganzes als auch in den meisten ehemals Weißen Nationen der nördlichen Hemisphäre rasch von den Weißen zu den Nicht-Weißen verschiebt, nimmt die durchschnittliche rassische Qualität derer, die dem Weißen Lager angehören, ab.

Das weltweite Rassengleichgewicht hat sich von 30 Prozent Weißen im Jahr 1900 auf knapp 20 Prozent Weiße im Jahr 1982 verschoben. Bis zum Ende des nächsten Jahrzehnts wird die Welt weniger als 16 Prozent Weiße haben. Die Bevölkerungsexplosion in der südlichen Hemisphäre, die für diese Rassenverschiebung verantwortlich ist, ist weitgehend die Folge des Exports weißer Wissenschaft und Technologie, die die Sterblichkeitsraten in Afrika, Indien und anderen nicht-weißen Gebieten der Welt dramatisch gesenkt haben.

Die Rassenvermischung der Nachkriegszeit ging mit einer enormen Zunahme interrassischer Vermehrung einher. Vor dem Krieg waren Eheschließungen zwischen Weißen und Schwarzen in den Vereinigten Staaten gesellschaftlich nicht akzeptabel und in vielen Bundesstaaten sogar illegal. Die wenigen Mulattenkinder wurden fast immer von schwarzen Müttern geboren und blieben in der schwarzen Rassengruppe. Nach dem Krieg wurden durch eine unerbittliche Propaganda alle rechtlichen und die meisten sozialen Hindernisse für die Rassenvermischung beseitigt, und die zweite Generation von Mischlingskindern nähert sich nun dem Fortpflanzungsalter.

Grimmige Rekapitulation. Um die gegenwärtige Situation der Weißen Rasse zu rekapitulieren:

Die geografische Ausbreitung der Weißen, die in den letzten vier Jahrhunderten die Regel war, wurde im 20. Jahrhundert mit dem Ende des europäischen Kolonialismus nicht nur gestoppt, sondern in der Zeit nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg umgekehrt.

Auf jeden Weißen, der auf dem Planeten lebt, kommen heute mehr als vier Nicht-Weiße, und das Verhältnis verschiebt sich immer schneller in Richtung eines noch größeren Übergewichts der Nicht-Weißen.

Die Prognosen sind ernst. Wenn sich die gegenwärtigen demografischen Trends noch ein halbes Jahrhundert lang unvermindert fortsetzen und wenn in dieser Zeit eine entschlossene und weitsichtige Minderheit von Menschen europäischer Abstammung keine nachhaltigen Anstrengungen unternimmt, um ein anderes Ergebnis zu erzielen, dann wird die Rasse, deren Geschichte wir in diesen 26 Teilen nachgezeichnet haben, das Ende ihrer langen Reise erreicht haben.

Sie mag noch ein weiteres Jahrhundert oder länger in isolierten Enklaven wie Island verweilen, und ihre charakteristischen Merkmale oder ihre Färbung werden im nächsten Jahrtausend mit abnehmender Häufigkeit bei Individuen wiederkehren, aber vor der Mitte des 21. Jahrhunderts wird der Punkt erreicht sein, von dem aus es kein Zurück mehr gibt.

Dann wird die Rasse, die den Ruhm Griechenlands und die Größe Roms begründete, die die Erde eroberte und ihre Herrschaft über alle anderen Rassen errichtete, die das Geheimnis des Atoms entschlüsselte und die Kraft nutzte, die die Sonne erhellt, die sich aus dem Griff der Schwerkraft befreite und nach neuen Welten ausgriff, in ewige Dunkelheit verschwinden.

Und die gegenwärtigen demographischen Trends werden sich fortsetzen, solange die politischen, religiösen und sozialen Konzepte und Werte, die derzeit das Denken der westlichen Völker und ihrer Führer umschreiben, weiterhin eine entscheidende Rolle spielen. Denn im Grunde ist es ein moralischer Defekt, der das Überleben der Rasse bedroht.

Wenn der Wille zum Überleben in den Weißen Massen vorhanden wäre und sie bereit wären, die notwendigen Maßnahmen zu ergreifen – was erfordern würde, dass sie gegen das Diktat der Religion handeln –, dann könnte die physische Bedrohung überwunden werden, mit Sicherheit und schnell. Die nicht-weiße Einwanderung könnte sofort und mit relativ geringem Aufwand gestoppt werden. Die Auswirkungen früherer nicht-weißer Einwanderung und der Rassenmischung rückgängig zu machen, wäre eine viel größere Aufgabe, die größere wirtschaftliche Anpassungen und zweifellos auch ein erhebliches Maß an Blutvergießen erfordern würde, aber es wäre eine Aufgabe, die durchaus im Rahmen der physischen Möglichkeiten der Weißen Mehrheit läge.

Diese Dinge könnten erreicht werden, selbst zu diesem späten Zeitpunkt. Und wenn sie erst einmal in einem großen Land vollbracht sind, könnten sie weltweit ausgedehnt werden, wenn auch vielleicht nicht ohne einen weiteren großen Krieg und die damit verbundenen Risiken. Aber natürlich werden sie nicht erreicht werden. Denn der Wille zum Überleben existiert nicht und er hat seit dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs in der weißen Bevölkerung keiner Großmacht mehr existiert. Die letzte Chance der Rasse, ihre Probleme auf diese relativ schmerzlose Weise zu überwinden, starb im Januar 1943 in Stalingrad.

In den nächsten Jahrzehnten wird also unweigerlich viel verloren gehen. Das Gleichgewicht der Bevölkerung wird sich überall noch schneller zugunsten der Nicht-Weißen, der Mischlinge und der Untauglichen verschieben. Die Welt wird ärmer, hässlicher, lauter, überfüllter und schmutziger werden. Aberglaube, Entartung und Korruption werden allgegenwärtig sein, selbst unter den Weißen von gesunder Rasse, und ein Großteil bester Rasse wird durch Rassenmischung für immer verschwinden.

Und die Unterdrückung wird sicherlich überall zunehmen: Denjenigen, die für Qualität statt Quantität und für rassischen Fortschritt eintreten, wird im Namen von „Freiheit“ und „Gerechtigkeit“ das Recht auf Widerspruch und das Recht auf Selbstverteidigung verweigert werden.

Letzten Endes muss jedoch keiner dieser Verluste entscheidend oder gar bedeutsam sein, so beängstigend sie jetzt auch sein mögen und so schrecklich sie in den unmittelbar bevorstehenden dunklen Jahren auch sein mögen. Alles, was wirklich wichtig ist, ist, dass ein Teil der Rasse überlebt, sich körperlich und geistig reinerhält, sich weiter fortpflanzt und schließlich über diejenigen siegt, die ihre Existenz bedrohen, selbst wenn dies tausend Jahre dauern sollte; und dieses Ergebnis sicherzustellen ist die dringende Aufgabe der rassisch bewussten Minderheit unseres Volkes in diesen gefährlichen Zeiten.

Einige Leitlinien. Eine detaillierte Ausarbeitung dieser Aufgabe würde den Rahmen dieser Serie sprengen, die, wie im Vorwort der ersten Folge erwähnt, lediglich dazu dient, den Lesern ein besseres Verständnis ihrer eigenen rassischen Identität zu vermitteln. Es mag jedoch angebracht sein, die Reihe Wer wir sind abzuschließen, indem wir die Lehren daraus ziehen, um einige sehr prägnante Leitlinien für die vor uns liegende Aufgabe aufzustellen:

1) Es ist eine Aufgabe für mindestens Jahrzehnte, wenn nicht Jahrhunderte. Geschichte zieht sich sehr zäh dahin; ein historischer Prozess von langer Dauer kann plötzlich in einem einzigen, katastrophalen Ereignis kulminieren, aber jede große Entwicklung in der Geschichte der Rasse hat tiefe Wurzeln und ist auf einem Boden gewachsen, der durch vorangegangene Entwicklungen gründlich vorbereitet wurde. Der Lauf der Geschichte ist jetzt, soweit es unsere Rasse betrifft, steil abwärts gerichtet, und seine Richtung zu ändern, wird nicht über Nacht geschehen, und dies wird auch nicht durch irgendwelche erfolgversprechenden Kinkerlitzchen erreicht werden, sondern es muss vorher ein Fundament für diesen Erfolg gelegt worden sein, Stein auf Stein, sorgfältig gesetzt.

2) Die Schaffenden, die diese Aufgabe übernehmen, werden nur eine winzige Minderheit der Rasse sein. Jedes Programm, das ein „Erwachen der Massen“ vorsieht oder sich auf die angeborene Weisheit der großen Masse unseres Volkes verlässt – also jedes populistische Programm – beruht auf einer falschen Vision und einem falschen Verständnis vom Wesen der Massen. In unserer langen Geschichte ist noch nie ein großer Schritt nach oben von der Masse der Bevölkerung vollzogen worden, sondern immer nur von einer außergewöhnlichen Person oder einigen wenigen außergewöhnlichen Individuen. Die Masse geht immer den Weg des geringsten Widerstandes, d. h. sie folgt immer der stärksten Fraktion. Es ist wichtig, mit den Massen zu arbeiten, sie zu informieren, sie zu beeinflussen, aus ihnen zu rekrutieren; aber man darf nicht auf ihre bestimmende, spontane Unterstützung zählen, bevor nicht eine kleine Minderheit aus eigener Kraft eine stärkere Kraft als jede gegnerische Gruppierung aufgebaut hat.

3) Die Aufgabe ist entsprechend ihrer Natur grundlegend, und sie wird nur durch einen grundlegenden Ansatz erfüllt werden können. Das heißt, dass diejenigen, die sich dieser Aufgabe widmen, einen reinen Geist und eine reine Seele haben müssen; sie müssen verstehen, dass ihr Ziel eine Gesellschaft ist, die auf ganz anderen Werten beruht als die, die der gegenwärtigen Gesellschaft zugrunde liegen, und sie müssen sich von ganzem Herzen und ohne Vorbehalt diesem Ziel verschreiben; sie müssen bereit sein, den ganzen Ballast an Fehlvorstellungen und das momentan gesellschaftlich Geschätzte hinter sich zu lassen. Es handelt sich also nicht um eine Aufgabe für Konservative oder Rechte, für „Gemäßigte“ oder Liberale oder für alle, deren Denken in den Irrtümern und der Korruption verhaftet ist, die uns auf den Abwärtskurs geführt haben, sondern es ist eine Aufgabe für diejenigen, die zu einem völlig neuen Bewusstsein der Welt fähig sind.

Die Aufgabe ist eine biologische, kulturelle und geistige, aber auch eine pädagogische und politische. Ihr Ziel hat nur in Bezug auf einen bestimmten Typus von Menschen einen Sinn, und wenn dieser Typus nicht erhalten werden kann, während die erzieherischen und politischen Aspekte der Aufgabe erfüllt werden, dann kann das Ziel nicht erreicht werden. Wenn die Aufgabe nicht in einer einzigen Generation erfüllt werden kann, muss es irgendwo ein soziales Milieu geben, das die mit dem Ziel verbundenen kulturellen und geistigen Werte widerspiegelt und verkörpert und dazu dient, diese Werte von einer Generation zur nächsten weiterzugeben. Die Erhaltung eines sozialen Milieus erfordert ebenso wie die Erhaltung eines Genpools ein gewisses Maß an Isolierung von fremden Elementen: je länger die Aufgabe dauert, desto höher ist das Maß. Dieses Erfordernis mag schwer zu erfüllen sein, aber es ist essentiell. Man sollte also eine Aufgabe ins Auge fassen, die sowohl einen internen, d. h. gemeinschaftsorientierten Aspekt als auch einen externen, d. h. politisch-pädagogischen Rekrutierungsaspekt hat. Mit dem Fortschreiten der Aufgabe und der Veränderung der äußeren und inneren Bedingungen wird sich zweifellos auch die Gewichtung der beiden Aspekte ändern.

* * *

Die hier gestellte Aufgabe ist gewaltig groß, und sie zu bewältigen wird einen größeren Willen, eine größere Intelligenz und eine größere Selbstlosigkeit erfordern, als sie unserer Rasse in irgendeiner früheren Krise abverlangt wurde. Die Gefahr, der wir uns jetzt gegenübersehen, sowohl durch den Feind innerhalb unserer Tore als auch durch den, der sich noch außerhalb befindet, ist größer als die, der wir uns durch die entrassten Römer im ersten Jahrhundert, die Hunnen im fünften Jahrhundert, die Mauren im achten Jahrhundert oder die Mongolen im 13. Jahrhundert gegenübersahen. Überwinden wir sie nicht, werden wir keine zweite Chance haben.

Bei all dem müssen wir uns klar machen, dass alle unsere Ressourcen im kommenden Kampf aus uns selbst kommen müssen; es wird keine Hilfe von außen geben, keine Wunder.

WDH – pdf 406

Most people who think they know Hitlerism, and many who witnessed or even participated in its struggle for power, will find this interpretation of the movement which, by transfiguring Germany, came so close to renovating the Earth and by so little! It was, they will say, the very opposite of a movement intended to put an end to the present ‘reign of quantity’, with all the mechanisation of work and of life itself that it implies. It was a doctrine visibly addressed to the working masses—‘pure-blooded’ masses—or supposed to be so, with healthy instincts, no doubt biologically superior to the Jewish elements of the ‘intelligentsia’, but ‘masses’ anyway.

Didn’t the organisation which represented the instrument of dissemination bear the eloquent name of ‘National Socialist German Workers’ Party’?[1] And didn’t the Führer, himself a product of the people, repeat over and over again in his speeches that only what comes from the people, or at least has its roots in them, is healthy, strong and great? Incidentally, the word völkisch has such a resonance in National Socialist terminology that it became highly suspect after the disaster of 1945. It is avoided in re-educated post-war Germany, almost as much as the words Rasse (race) and Erbgut (heredity).

But there is more: the Führer seems to have aimed, as few men responsible for the destinies of a great people have done in the modern world, at three goals most in keeping with the spirit of our age: ever-greater technical perfection, ever-greater material well-being and indefinite demographic growth—more and more births in all healthy German families, even outside the family framework, provided the parents were healthy and of good breeding.

It is certain that most of the statements which illustrate the first and last of these aims are justified by the state of war that threatened Germany at the time they were made. Here is one, for example, from 9 February 1942: ‘If I now had a bomber capable of flying at more than seven hundred and fifty kilometres an hour, I would have supremacy everywhere… This aircraft would be faster than the fastest fighters. Therefore, in our manufacturing plans we should first tackle the bombers problem’… ‘Ten thousand bombs dropped randomly on a city are not as effective as a single bomb dropped with certainty on a power station, or on the pumping stations on which the water supply depends’.[2]

And further: ‘In the war of technology, it is the one who arrives at the right time with the right weapon who wins the decision. If we succeed in bringing our new panzer on line this year, at the rate of twelve per division, we will overwhelmingly outclass all the armoured vehicles of our adversaries… What is important is to have technical superiority at least on a decisive point. I admit it: I am a technical fanatic. You have to come up with something new that surprises your opponent so that you always keep the initiative’.

One could multiply such quotations ad infinitum taken from the Führer’s talks with his ministers or generals. They would only prove that he had a sense of reality, the absence of which would be surprising, to say the least, in a warlord.

The same applies to Adolf Hitler’s ideas about the need for a large number of healthy children. His point of view is that of a legislator, and therefore of a realist; and not only of someone who knows how to draw the right conclusions from the observations he himself has made—someone who, among other things, knows the consequences that a pernicious policy of anti-natalism has had for France but of one who understands the lessons of history and wants to make his people benefit from them.

The same applies to Adolf Hitler’s ideas about the need for a large number of healthy children. His point of view is that of a legislator, and therefore of a realist; and not only of someone who knows how to draw the right conclusions from the observations he himself has made—someone who, among other things, knows the consequences that a pernicious policy of anti-natalism has had for France but of one who understands the lessons of history and wants to make his people benefit from them.

The Ancient World, he stressed, owed its downfall to the restriction of births among the patricians and to the passage of power into the hands of the most diverse races of plebs ‘on the day when Christianity erased the border which, until then, separated the two classes’.[3] And he concluded, a little further on: ‘It is the baby bottle that will save us’. His viewpoint is also that of a conqueror conscious of the perenniality of natural law, that wants ‘the worthiest’ to be ultimately, in the eyes of Destiny, the strongest, conscious and therefore of the necessity for a missioned people—a people of the future to be the strongest.

Adolf Hitler dreamed of Germanic expansion in the East. He said so, and repeated it. It appears, however, that there was a difference between this dream and that of those conquerors of the East or West who had only the lucrative adventure in mind.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: This is precisely why I don’t identify at all with the Castilians who conquered Mexico. These idiots were only chasing gold, and the first thing they did when they stepped on the shores of the new continent was to fornicate with Indian women. It also explains why I have zero male friends in this country. Spanish-speaking liberals are bananas, and no one among the Criollo conservatives wants to see the damage that blood mixing caused in the Americas.

Savitri goes on to quote the Fuhrer:

______ 卐 ______

I would consider it a crime’, he said in the same talk on the night of 28-29 January 1942, ‘to have sacrificed the lives of German soldiers simply for the conquest of material wealth to be exploited in the capitalist style. According to the laws of Nature, the land belongs to whoever conquers it. Having children who want to live; the fact that our people are bursting at the seams within their narrow borders, justifies all our claims on the Eastern spaces. The overflow of our birth rate will be our chance. Overpopulation forces a people to get out of the woods. We are not in danger of remaining frozen at our present level. Necessity will force us to always be at the forefront of progress. All life is paid for in blood’.[4]

Elsewhere, in a talk on the night of 1 to 2 December 1941, he said: ‘If I can admit a divine commandment it is this: ‘The species must be preserved. [Editor’s note: Gens alba conservanda est!] Individual life must not be valued at too high a price’.[5]

____________

[1] Nationalsozialistische Deutscher Arbeiter Partei (hence NSDAP).

[2] Libres propos sur la guerre et la paix, translation by Robert d’Harcourt, p. 297-98.

[3] Ibid, p. 254.

[4] Ibid, pp. 254-255.

[5] Ibid, p. 139.

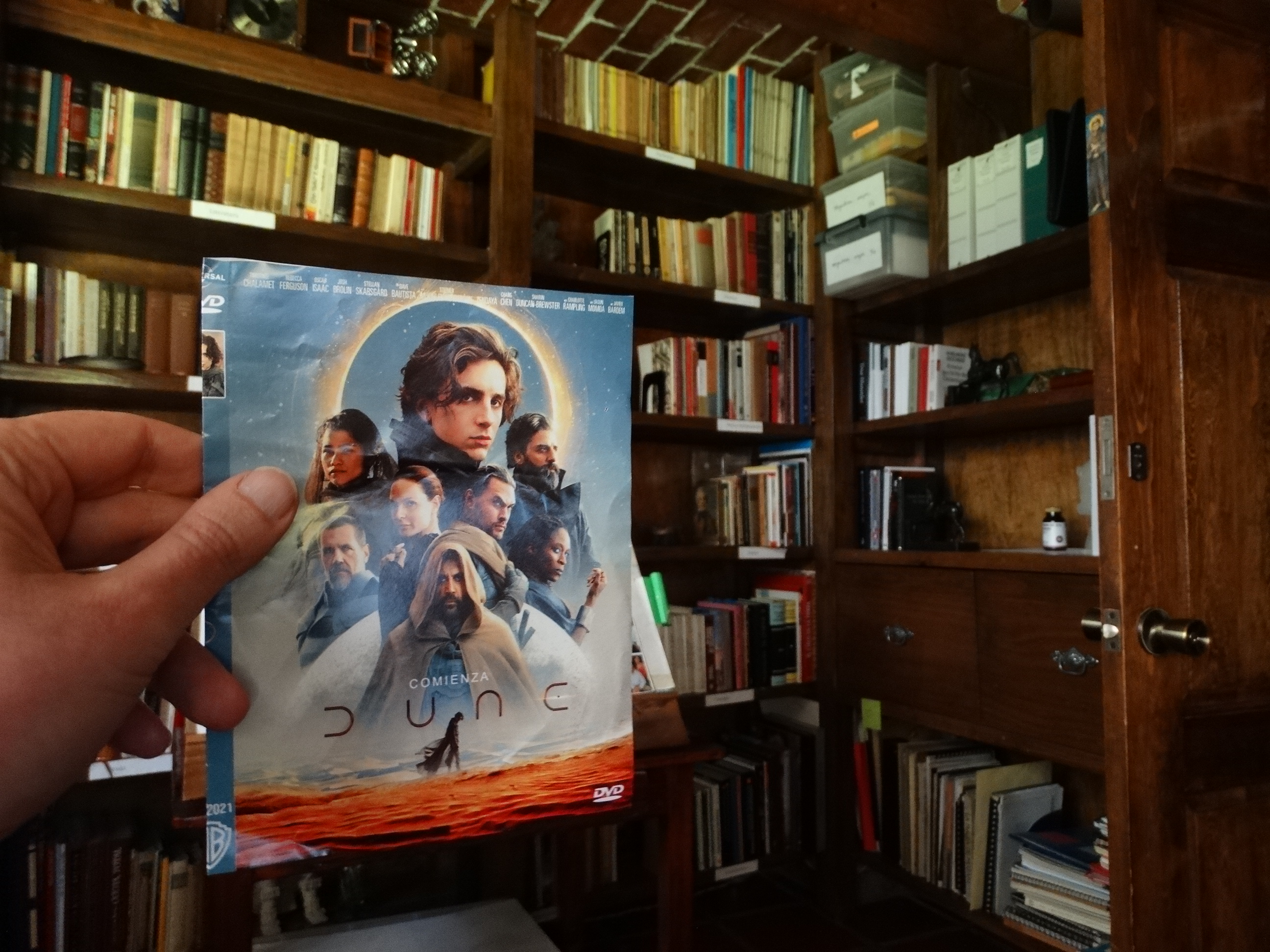

On Mondays a ‘market on wheels’ passes near my house that doesn’t exist in the neighboring country to the north: Indians who sell food and other household items to the more bourgeois classes. For the ridiculous price of $15 pesos (0.72 dollars) yesterday I bought this year’s version of Dune.

On Mondays a ‘market on wheels’ passes near my house that doesn’t exist in the neighboring country to the north: Indians who sell food and other household items to the more bourgeois classes. For the ridiculous price of $15 pesos (0.72 dollars) yesterday I bought this year’s version of Dune.

I still remember when I saw the first film version of Frank Herbert’s novel in 1984 and I thought it was a very bad movie. But the 2021 version is worse as the accelerating trend toward Evil continues in these eschatological times, as Savitri would say. I mean the mania of putting more and more non-white actors on the big screen. The $15 pesos I spent yesterday for a pirated DVD of Dune was a good investment, as I prefer to give that amount to an Indian than to Hollywood dogs (tonight my sister and my nephew will watch Dune on the Imax screen).

Although, with the exception of this darkening of actors, the visual aspect of the 2021 film improves on previous versions, there will never be a good movie because Herbert’s novel is flawed.

When I saw the 1984 film, I was unaware of the existence of psychoclasses. Recently, in one of my comments on Savitri’s book, I said that the Spaniards belonged to a higher psychoclass than the Aztecs, who killed and ate their children. The mistake of Herbert and all fans of science-fiction is that they ignore the existence of psychoclasses. With the exception of the books that I’ve been promoting on this site from the pen of Arthur C. Clarke, the only thing that the authors of the futurist genre do is extrapolate the present of this fallen West to a future where technology has been developed.

But that is not the future.

During the Middle Ages in Europe, the future of the Mesoamerican and Inca world would be the destruction, thanks to the Europeans, of an infanticidal psychoclass, a psychoclass of serial killers (see the central part of my Day of Wrath) through an amalgamation between Indian and Spanish in which, at least, the filicide aspects of the Amerinds were overcome.

That doesn’t mean that I identify myself with the Castilians. I represent a psychoclass superior to theirs inasmuch as I have always been repulsed by bullfighting (as I tell in one of my autobiographical books, my grandmother and my godmother were fans of this sadistic art). In other words, internally I already made another quantum leap from the Spanish psychoclass to a psychoclass that feels infinitely more empathy for animals.

The mistake of Herbert, who once had a personal fight with Clarke, is that he was blind to psychogenic evolution; that is, to the development of empathy (think about how Hitler’s first measure when he came to power was to pass laws to prevent the cruelty to animals). Herbert extrapolates the human psychoclass from our time to the future as if there won’t be any psychogenic breakthroughs. For example, one of the anachronisms of the movie that I saw yesterday is the hobby of the House Atreides (the movie’s good guys), who had representations of bullfighting art in their palace, including the head of a sacrificed bull on a wall.

In fact, it is impossible for the current psychoclass of humans to grow indefinitely because with such advanced technology they would only end up self-destructing (which is why we receive no signs of intelligent life in the Milky Way). Only the Aryan overman, the followers of a new Hitlerite religion, could inherit the stars.

Unlike Herbert’s Dune, in a few of Clarke’s futuristic novels humans stop abusing children and animals. When in 1992 I wrote him a letter, and asked him what was his favourite novel among the many he wrote, the famous British author informed me that it was The Songs of Distant Earth (except for my address that I’ve just deleted, Clarke’s letter can be read: here). The novel has its problems, of course. Clarke was bisexual and this shows in The Songs of Distant Earth. But at least he acknowledges that psychoclasses may evolve in the future.

But I would like to say one more thing about the darkening of the actors in the 2021 version of Dune and Hollywood in general.

Yesterday I saw a segment of Fox News. The axiological lie on which the US is based, a lie that is exterminating the white race in that country, is something that even anchors like Tucker Carlson share. Last night Carlson said: ‘…the funding principle of the United States, to sum up, is the Christian belief that all people, regardless of their skin color, are equal before God’.

Well, they certainly aren’t equal before me.

It is the bloodshed that accompanied the seizure of power by these ideological movements that gives the illusion. We readily imagine that killing is synonymous with revolution and that the more a change is historically linked to massacres, the more profound it is in itself. We also imagine that it is all the more radical the more visibly it affects the political order. But this is not the case. One of the most real and lasting changes in known history, the transition of multitudes of Hindus of all castes from Brahmanism to Buddhism between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC, took place not only without bloodshed, without revolution in the popular sense of the word, but without the least political upheaval. Nevertheless, Buddhism, even though it was later practically eliminated from India, has left its mark on the country forever.[1]

Marxism-Leninism is, despite the persecutions, the battles, the mass executions, the tortures, the slow deaths in the concentration camps and the political overthrows which have everywhere accompanied its victory, far too much ‘in line’ with the evolution of the West—and of the world, increasingly dominated by Western technology, to deserve the name of ‘revolutionary doctrine’.

Fundamentally, it represents the logical continuation, the inevitable continuation, of the system of ideas and values which underlies and sustains the world which arose both from the French Revolution and the increasing industrialisation of the 19th century; the seeds of this system were already found in the quasi-religious respect of the Jacobins for ‘science’ and its application to the ‘happiness’ of the greatest number of men, all ‘equal in rights’ and before that, the notion of ‘universal conscience’ linked to ‘reason’: the same for all, as it appears in Kant, Rousseau and Descartes.

It represents the logical continuation of that attitude which holds as legitimate any revolt against a traditional authority in the name of ‘reason’, ‘conscience’ and above all of the so-called ‘facts’ brought to light by ‘scientific’ research. It completes the series of all these stages of human thought, each of which constitutes a negation of the hierarchical diversity of beings, including men: an abandonment of the primitive humility of the sage, before the eternal wisdom; a break with the spirit of all traditions of more than human origin. It represents, at the stage we have reached, the natural culmination of a whole evolution which merges with the very unfolding of our cycle: unfolding which accelerates, as it approaches its end, according to the immutable law of all cycles.

It has certainly not ‘revolutionised’ anything. It has only fulfilled the possibilities of expressing the permanent tendency of the cycle, as the increasingly rapid expansion of technology coincides with the pervasive increase in the population of the globe. In short, it is ‘in line’ with the cycle, especially the latter part of it.

Christianity was, of course, at least as dramatic a change for the Ancient World as victorious Communism is for today’s world. But it had an esoteric side that linked it, despite everything, to Tradition from which it derived its justification as a religion. It was its exoteric aspect that made it, in the hands of the powerful who encouraged or imposed it, first of all in the hands of Constantine, the instrument of domination assured by a more or less rapid lowering of the racial elites; by a political unification from below.[2]

It is this same exoteric aspect, in particular the enormous importance it gave to all ‘human souls’, that compels Adolf Hitler to see in Christianity the ‘prefiguration of Bolshevism’: the ‘mobilisation, by the Jew, of the mass of slaves to undermine society’, the egalitarian and anthropocentric doctrine, anti-racist to the highest degree, capable of winning over the countless uprooted of Rome and the Romanised Near East. It is this doctrine that Hitler attacks in all his criticisms of the Christian religion, in particular in the comparison he constantly makes between the Jew Saul of Tarsus, the St. Paul of the Churches, and the Jew Mardoccai, alias Karl Marx.

It is this same exoteric aspect, in particular the enormous importance it gave to all ‘human souls’, that compels Adolf Hitler to see in Christianity the ‘prefiguration of Bolshevism’: the ‘mobilisation, by the Jew, of the mass of slaves to undermine society’, the egalitarian and anthropocentric doctrine, anti-racist to the highest degree, capable of winning over the countless uprooted of Rome and the Romanised Near East. It is this doctrine that Hitler attacks in all his criticisms of the Christian religion, in particular in the comparison he constantly makes between the Jew Saul of Tarsus, the St. Paul of the Churches, and the Jew Mardoccai, alias Karl Marx.

But it could be said that Christian anthropocentrism, separated of course from its theological basis, already existed in the thought of the Hellenistic and then the Roman world; that it even represented, more and more, the common denominator of the ‘intellectuals’ as well as the plebs of these worlds. I even wonder if we do not see it taking shape from further back, because in the 6th century BC Thales of Miletus thanked, it is said, the Gods for having created him ‘to be human, and not animal; male, not female; Hellene, not Barbarian’ meaning a foreigner.

It is more than likely that, already in Alexandrian times, a sage would have rejected the last two, especially the last one!, of these three reasons to give thanks to Heaven. But he would have retained the first. And it is doubtful that he would have justified it with as much simple common sense as Thales.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: Here I agree with Thales. But keep in mind that if Thales had not been an Aryan, I’d agree with Savitri. The point is that only the most beautiful specimens of the Aryan race are the image and likeness of divinity. The rest are, using the language of the priest of the 14 words, exterminable Neanderthals.

______ 卐 ______

Now any exaltation of ‘man’ considered in himself, and not as a level to be surpassed, automatically leads to the over-estimation of both the masses and individuals with interesting hands; to a morbid concern for their ‘happiness’ at any cost; therefore, to an utilitarian attitude above all in the face of knowledge as well as of creative action.

In other words, if, on the one hand, in the Hellenistic world—then in the Roman world—esoteric doctrines more or less related to Tradition—that is, doctrines ‘above Time’—have flourished within certain schools of ancient wisdom—among the Neo-Platonists, the Neo-Pythagoreans and certain Christians—it is, on the other hand, quite certain that all that conquering Christianity (exoteric, and to what degree!) was, as was the widespread interest in the applications of experimental science, in the direction of the Cycle.

The fact that the Churches have, later on in the centuries opposed the statement of several scientific truths, ‘contrary to dogma’ or supposedly so, doesn’t change anything. This is, in fact, a pure rivalry between powers aiming at the ‘happiness of man’—in the other world or this one—and embarrassing each other as two suppliers of similar commodities.

If the Churches today are giving more and more ground, if they are all (including the Roman Church) more tolerant of those of their members who like Teilhard de Chardin give ‘science’ the largest share, it is because they know that people are more and more interested in the visible world and the benefits that flow from its knowledge, and less and less to what cannot be seen or ‘proved’—and they do what they can to keep their flock. They ‘go with the flow’ while pointing out as often as possible that the anthropocentric ‘values’ of the atheists are, in fact, their own; that they even owe them, without realising it.

No doctrine, no faith linked to these values is ‘revolutionary’ whatever the arguments on which it is based, whether drawn from a ‘revealed’ morality or from an economic ‘science’.

The real revolutionaries are those who militate not against the institutions of one day, in the name of the ‘sense of history’, but against the sense of history in the name of timeless Truth; against this race to decadence characteristic of every cycle approaching its end, in the name of their nostalgia for the beauty of all great beginnings, of all the beginnings of cycles.

These are precisely those who take the opposite view of the so-called ‘values’ in which the inevitable decadence inherent in every manifestation in Time has gradually asserted itself and continues to assert itself. They are, in our time, the followers of the one I have called ‘the Man against Time’, Adolf Hitler. They are, in the past, all those who, like him, have fought against the tide, the growing thrust of the Forces of the Abyss, and prepared his work from far and near—his work and that of the divine Destroyer, immensely harder, more implacable, further from man than he, whom the faithful of all forms of Tradition await under various names ‘at the end of the centuries’.

__________

[1] The same could be said of Jainism, which still has one or two million followers there.

[2] Racial purity no longer played any role under Constantine. And even in the Germanic but Christian empire of Charlemagne much later, a Christian Gallo-Roman had more consideration than a Saxon or other pagan German.

Honor the fallen

Chapter VII

Technical development

and ‘fight against time’

‘What a sun, warming the already old world

shall ripen the glorious labours again

who shone in the hands of virile nations?’

Leconte de Lisle (L’Anathème’, Poèmes Barbares)

It should be noted that the Churches, which theoretically should be the custodians of all that Christianity may contain in terms of eternal truth, [1] have only opposed scholars when the latter’s discoveries tended to cast doubt on, or openly contradicted, the letter of the Bible. (Everyone knows Galileo’s disputes with the Holy Office about the movement of the Earth.)

But there was never, to my knowledge, any question of their protesting against what seems to me to be the stumbling block to any unselfish research of the laws of matter or life; namely, against the invention of techniques designed to thwart natural purpose—what I shall call techniques of decadence. Nor did they denounce and condemn categorically, because of their inherently odious character, certain methods of scientific investigation such as all forms of vivisection.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: They don’t mind tormenting animals because they are Neanderthals; that is to say, they belong to an inferior psychoclass to ours: just as the pre-Columbian Amerinds belonged to an inferior psychoclass to that of the Spaniards. Is this passage from my Day of Wrath remembered (in the chapter ‘Sahagún’s exclamation’)?:

I don’t believe that there is a heart so hard that when listening to such inhuman cruelty, and more than bestial and devilish such as the one described above, doesn’t get touched and moved by the tears and horror and is appalled; and certainly it is lamentable and horrible to see that our human nature has come to such baseness and opprobrium that [Aztec] parents kill and eat their children, without thinking they were doing anything wrong.

Like Sahagún, the priestess and the priest of the four words (‘eliminate all unnecessary suffering’) throw our hands up in horror when the man of today torments defenceless creatures, to the point of precognizing the appearance of a Kalki who avenges them (and us). Savitri continues:

______ 卐 ______

They could not, given the anthropocentrism inherent in their very doctrine. I recalled above that the vision that the esoteric teaching of Christianity opened to its Western initiates in the Middle Ages did not go beyond ‘Being’. But no exoteric form of Christianity has ever gone beyond ‘man’. Each of them affirms and emphasises the ‘apartness’ of that being, privileged whatever his individual worth (or lack of it) whatever his race or state of health. Each one proclaims concern for his own best interest, and the help it offers him in the search for his ‘happiness’ in the hereafter, certainly, but already in this lower world. Each of them is concerned only for him, ‘man’, always man, contrary even to the ‘exoterisms’ of Indo-European origin (Hinduism; Buddhism) which insist on the duties of their followers ‘towards all beings’.

______ 卐 ______

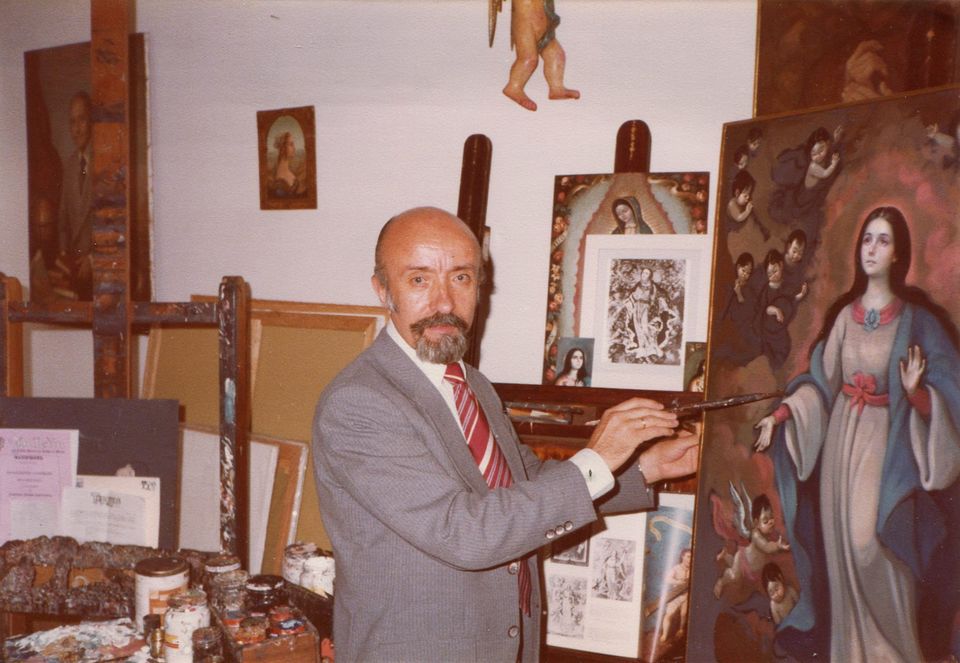

Editor’s Note: Remember my post from exactly a month ago: This very Catholic painter asked me at a family dinner: “¿Por qué los animales todavía existen?” (‘Why do animals still exist?’).

______ 卐 ______

It is, I think, precisely to this intrinsic anthropocentrism that Christianity owes the short duration of its positive role in the West insofar as, despite all the horror attached to the history of its expansion, a certain positive role can be attributed to it. Once weakened and death, the influence of its true spiritual elite—that which, until perhaps the 14th or 15th century, was still attached to Tradition—nothing was easier for the European than to move from Christian anthropocentrism to that of the rationalists, theists or atheists; to replace the concern for the individual salvation of human ‘souls’, all considered infinitely precious, by that of the ‘happiness of all men’ at the expense of other beings and the beauty of the earth, due to the proliferation of the techniques of hygiene, comfort and enjoyment within the reach of the masses.

Nothing was easier for him than to continue to profess his anthropocentrism by merely giving it a different justification, namely, by moving from the notion of ‘man’, a privileged creature because he was ‘created in the image of God’—and, what is more, of an eminently personal ‘god’—to that of ‘man’: the measure of all things and the centre of the world because he’s ‘rational’, that is to say, capable of conceiving general ideas and using them in reasoning; capable of discursive intelligence hence of ‘science’ in the current sense of the word.

The concept of ‘man’ indeed underwent some deterioration in the process. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry has shown, the human individual, deprived of the character of ‘creature in the image of God’ that Christianity conferred on him, finally becomes a number within a pure quantity and a number that has less and less importance in itself. Understandably, everyone is sacrificed ‘to the majority’. But we no longer understand why ‘the majority’, or even a collectivity of ‘a few’, would sacrifice themselves or even bother for another one.

Saint-Exupéry sees the survival of a Christian mentality in the fact that in Europe, even today, hundreds of miners will risk their lives to try to pull one of them out of the hole where he lies trapped under the debris of an explosion. He predicts that we are gradually moving towards a world where this attitude, which still seems so natural to all of us, will no longer be conceivable.

Perhaps it is no longer conceivable in communist China. And it should be noted that, even in the West where it is still conceivable, the majorities are less and less inclined to impose simple inconveniences on themselves to spare one or two individuals, not of course of death but discomfort and even real physical suffering. The man who is most irritated by certain music, and who isn’t sufficiently spiritually developed to isolate himself from it by his asceticism, is forced to endure, in the buses, and sometimes even in the trains or planes, the common radio or the transistor of another traveller if the majority of passengers tolerate it or even more so enjoy it. They are not asked for their opinion.

One can, if one wishes, with Saint-Exupéry, prefer Christian anthropocentrism to that of the atheistic rationalists, fervent of experimental sciences, technical progress and the civilisation of well-being.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: This is true, and the best way to show it is to compare the most famous television series introducing the West: Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation (1969), Jacob Bronowski’s The Ascent of Man (1973) and Carl Sagan’s Cosmos (1980). Obviously, the series by Christian Clark has its problems, but at least he transmits the spirit of the Aryan through art. Bronowski and Sagan on the other hand present civilisation from the point of view of science and technology: something that betrays the essence of the Aryan and his notion of the numinous.

______ 卐 ______

It is a matter of taste. But I find it impossible not to be struck by the internal logic that leads, without a solution of continuity, from the first to the second and from the latter to Marxist anthropocentrism for which man—himself a pure ‘product of his economic environment’—taken en masse is everything; taken individually, worth only what his function in the increasingly complicated machinery of production, distribution and use of material goods for the benefit of the greatest number. It seems to me impossible not to be struck by the character quite other than revolutionary and of Jacobinism at the end of the 18th century; and Marxism (and Leninism), both in the 19th and in the 20th.

____________

[1] Offered to the faithful through the symbolism of sacred stories and liturgy.

Focus within

‘Everything great comes from within. Learn to raise above yourself, to give birth to a rising star, so you can triumph over the world’.

But this slowly decadent Hellenic world, which, after having been subjected to Christianity was only to be reborn to detach itself more and more from ‘Europe’ without being able or willing, even today, to integrate with it, is characterised by the boom in experimental sciences and their applications.

The thirst to study the phenomena of Nature and to discover its laws (that satisfy reason and is becoming more widespread as the traditional science of the priests of Greece and Egypt, fruit from a direct intellectual intuition of the very principle of these laws) becomes rarer there. And above all, there was a growing determination, as there was later during the Renaissance and even more so in the 19th and 20th centuries, to use these physical laws to construct devices of practical use—such as the endless screw, the inclined screw and forty other machines whose invention is attributed to Archimedes such as the ‘burning mirrors’, enormous magnifying glasses using which this same man of genius set fire to the Roman ships that blocked Syracuse, or the ‘compression fountains’, or robots, of Heron.

Anatomy, physiology and the medical art which is based on both are, and this too is to be noted, in the spotlight. If it is true that in the 17th century Aselli and Harvey were already foreshadowing Claude Bernard, it is no less true that at the end of the 4th century B.C., two thousand years earlier, Erasistratos and Herophilus were foreshadowing not only Aselli and Harvey but also the famous physiologists, physicians and surgeons of the 19th and 20th century.

Of course, there is a long way to go from Herophilus’ automata to modern computers, just as there is a long way to go from Herophilus’ dissections and, four hundred years later, Galen’s dissections, however horrific they may have been, to the atrocities of organ or head transplanters, or even to those of cancer specialists, carried out today in the name of scientific curiosity and ‘in the interest of mankind’.

There is a long way to go in terms of results, from the embryonic technique of the Hellenistic world, and later the Roman world, to that which we see developing in all areas around us, and even to that of the 16th century. But it is no less true that in these two periods when a form of traditional religion relaxed before being definitively cut off from its esoteric base, there was a resurgence of interest in the experimental sciences and their applications, a reawakening of man’s desire to dominate the forces of Nature and living beings of other species than his own, with a view to the profit or convenience of as many people as possible.

This is not yet the excessive mechanisation and mass production that the 19th century would inaugurate in Europe and that the 20th intensified with all the consequences that we know. But it was already the spirit of the scientists whose work had, in one way or another, prepared this evolution: the spirit of experimental research to apply the information gained to the material comfort of man, to the simplification of his work and the prolongation of his physical life, that is to say, to the fight against natural selection.

The machine enables the individual or the group to succeed without innate strength or special ability, and the drug or the surgical operation prevents even the most useless and uninteresting patient from leaving the planet and giving up his place to the healthy man, more valuable than he.

It is difficult not to be impressed by the ever-increasing importance, both in the last centuries of the ancient world, in the early modern period, and in our own time, of experimentation on living beings to gain more complete information about the structure and functions of bodies and apply it to the art of healing—or trying to heal at any cost. These are times when, as today, the physician, the surgeon and the biologist are honoured as great men and when vivisection—older, of course, since as early as the sixth century B.C. Alcmaeon is said to have dissected animals, but increasingly encouraged thanks to unrestricted anthropocentrism—is regarded as a legitimate method of scientific research.

There are, therefore, precedents. And we would no doubt find others, corresponding to other collective declines, if the history of the world were better and more uniformly known. But it seems that the further back in time we go, the less certain traits that bring the most sophisticated ancient civilisations closer to today’s mechanised world are evident. I am thinking, for example, of those very old metropolises of the so-called Indus Valley civilisation, Harappa and Mohenjodaro, where archaeologists have attested to the existence of seven- or eight-storey buildings, and pointed to the enormous mass production of earthenware vessels and other objects, all of them perfectly made but all hopelessly similar. How can we not be struck by this uniformity in quantity and imagine, in the workshops from which these mass-produced objects emerged, on the assembly line, a robotization of the worker that already, five or six thousand years later, prefigured that of the ‘human material’ of our factories?

And how can we fail to see in the successive Aryan invasions which, from the 4th millennium before the Christian era if not earlier, that came up against this ultra-organised world—mechanised, as far as it was possible at the time—and destroyed it (while assimilating, certainly, the best that its elite could offer). How can we fail to see in them the blessed instruments of a recovery?

How can we fail to see in their work the installation of the Vedic civilisation in India: a halt, at least momentarily, in the downward march of the Vedic civilisation?: a halt in the downward march that the course of our Cycle represents, especially in the Dark Age, then close to its beginning: an attempt to fight ‘against Time’ undertaken by the Aryas under the impulse of the Forces of Life as were to be undertaken, centuries later, still driven by these same Forces by invaders of the same race, the Hellenes and Latins at the decline of the Aegean and Italic cultures, technically too advanced; the Romans, at the decline of the Hellenistic world, the Germans, at the decline of the Roman world?

But the hold of mechanisation on the civilisation of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro—modest mechanisation, moreover, since it was still only a matter of mass production of crafts—was to be less fatal than that which the Mediterranean and then the Western world underwent, respectively in the time of Archimedes, then Heron and the ergastulas of Carthage, Alexandria, then Rome, and in the 18th century and especially the 19th and nowadays. The world of the Indus Valley still had, even in its decline, something else to give to its successors than recipes for production. It is said that they learned at least some forms of Yoga. In the same way, the Hellenistic and later the Greco-Roman world even in its most advanced decadence retained, if only in the Neo-Pythagoreans and Neo-Platonists, something of the essence of ancient esotericism. This was, along with what was eternal in the teaching of Aristotle, assimilated into esoteric Christianity, survived in Byzantium and gave rise there, as well as in the West throughout the Middle Ages, to the flowering of beauty that we know: beauty is the visible radiation of Truth.

But the hold of mechanisation on the civilisation of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro—modest mechanisation, moreover, since it was still only a matter of mass production of crafts—was to be less fatal than that which the Mediterranean and then the Western world underwent, respectively in the time of Archimedes, then Heron and the ergastulas of Carthage, Alexandria, then Rome, and in the 18th century and especially the 19th and nowadays. The world of the Indus Valley still had, even in its decline, something else to give to its successors than recipes for production. It is said that they learned at least some forms of Yoga. In the same way, the Hellenistic and later the Greco-Roman world even in its most advanced decadence retained, if only in the Neo-Pythagoreans and Neo-Platonists, something of the essence of ancient esotericism. This was, along with what was eternal in the teaching of Aristotle, assimilated into esoteric Christianity, survived in Byzantium and gave rise there, as well as in the West throughout the Middle Ages, to the flowering of beauty that we know: beauty is the visible radiation of Truth.

But of the treasures of the Middle Ages—of all that it had preserved of the eternal Indo-European Tradition, despite its rejection of the forms that this had taken in Germania and in the whole of the north of the continent, as in Gaul before the appearance of Christianity—the narrowly ‘scientific’ spirit of the Renaissance, and above all of the centuries that followed, wanted, or was able, to retain nothing. If we are to believe René Guénon and a few other well-informed authors, these treasures would have been put beyond the reach of the West as early as the 14th century, or at the very least the 15th, as soon as the last direct heirs of the secret teachings of the Order of the Temple disappeared.

The interest of so many 19th-century writers in the Middle Ages remains, like the 16th-century infatuation with classical antiquity and Greco-Roman mythology, attached to the most picturesque and superficial aspects of that past. The proof is that, for them, it goes hand in hand with the most naive belief in ‘progress’ and the excellence of generalised literacy as the surest way to hasten it (we may recall the pages of Victor Hugo on this subject). The link with immemorial Indo-European wisdom, and even with the little that Christianity has managed to assimilate from it after having destroyed—by snatch or by violence, from the Mediterranean to the North Sea and the Baltic—all the exoteric expressions, is indeed cut.

And it is in the place of this ancient wisdom that the West is seeing a true religion of the laboratory and the factory take shape and spread and flourish: a stubborn faith in the indefinite progress of man’s power, and I repeat, of any ‘man’, ensured by the ‘enslavement’ of the forces of Nature, that is to say, their use in parallel with the indefinitely increased knowledge of its secrets. It is in its place that he sees it imposing itself, and no longer alongside it, as in India or Japan and wherever peoples of ‘traditional’ civilisation have, reluctantly, and while clinging to their souls, accepted modern techniques.

This leads to the ‘conquest of the atom’ and the ‘conquest of space’ (so far, of the tiny space between our Earth and the Moon; less than half a million of our poor kilometres). But we are not discouraged. Soon, say our scientists, it will be the entire solar system that will fall within the ‘domain of man’. The solar system and then, for why stop?, ever-larger portions of the physical Beyond ‘without bottom or edge’. This also leads—at the cost of what horrors of experimentation on a world scale!—to the Luciferian dream of the indefinite prolongation of corporeal life with, already, the terrible practical consequence of the efforts made so far to reach it: the unrestrained pullulation of man, and more particularly of the lower man at the expense of the noblest flora and fauna of the earth and of the human racial elite itself.