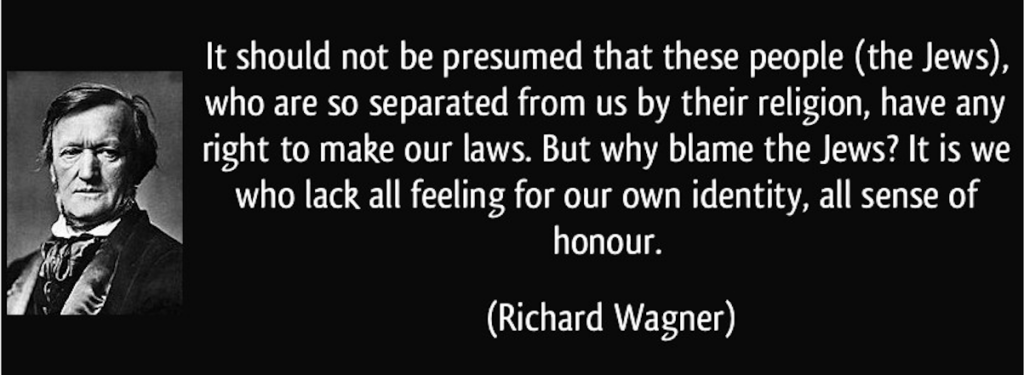

Category: Richard Wagner

Crusade

against the Cross, 13

If I were to write a cold but informative article, I would say that by 1879 Nietzsche’s health worsened with headaches, eye pains and continuous vomiting.

On 2 May he called in sick and gave up his professorship in Basel. He travelled for the first time to the Upper Engadine, where he spent his summers from that year onwards. He spent the winter in Naumburg with his family. In the early 1880s, he went to Riva on Lake Garda and later to Venice, where he studied Christianity intensively. Nietzsche spent August in Marienbad and the next couple of months in Naumburg. He then spent his first harsh winter in Genoa and in November published The Wanderer and His Shadow (added to Human, All Too Human). In 1881 he published The Dawn of Day and spent his first summer in Sils-Maria. In August he was assailed by the thought of the eternal return and in October he heard Bizet’s Carmen.

But I don’t like the informative style of encyclopaedias: it robs us of the real person and his inner experiences. The real Nietzsche then wrote things like ‘I can’t read, I can’t deal with people’. This flesh-and-blood Nietzsche implored his friend Overbeck, the theologian, to visit him: his wish was granted. Nietzsche’s joy was unbelievably great, as Overbeck later recounted.

These were times when Nietzsche had already established his mode of work as walking in solitude for several hours until his best thoughts came to him, which he would catch on the fly from his walks in his notebook. Rhode had distanced himself from the philosopher, but not from the person, the friend; and the pains in his eyes meant that even his mother had to read books to him on his visits to Naumburg.

Nietzsche was very depressed by the climate in his hometown. ‘Unfortunately, this year the autumn in Naumburg has turned out so cloudy and wet’, he wrote, where he continued to have horrible attacks of vomiting. ‘I can only endure the existence of walking, which here, in this snow and cold, is impossible for me’. To Overbeck, he wrote: ‘Last year I had 118 attacks’. But what is relevant for us was still the Wagner case, who, about his former friend, wrote in his notes: ‘Again one must be surprised at this apostasy’. On 19 October 1879, Wagner wrote to Overbeck:

How would it be possible to forget this great friend, separated from me?… It grieves me to have to be so totally excluded from taking part in Nietzsche’s life and notes. Would it be immodest of me to beg you cordially to send me some news about our friend?

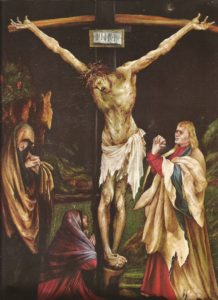

A week later the report of Nietzsche’s disconsolate state reached him. At the end of December Wagner dares to read The Wanderer and his Shadow and even reads some passages to Cosima. ‘To have nothing but derision for so lofty and sympathetic a figure as Christ!’, Richard exclaimed angrily.

The old composer was by then already in poor health, and like Nietzsche, he was burdened by the ‘permanently grey Bayreuth winter sky’, so he went to Italy for the winters. Nietzsche, for his part, spent four months with his new assistant, nicknamed Peter Gast, who read aloud to him: times for his book The Dawn of Day, which in some ways prefigures The Antichrist as far as the critique of compassion is concerned. (To try to understand Nietzsche we have to contextualise his philosophy in the present, where neo-Christian compassion taken to the extreme has led us to normalise pathologies such as those suffered by trans people: unwise levels of compassion that we have been calling ‘deranged altruism’. And the same can be said of Christian and neo-Christian love for marginalised black people: unbridled compassion.)

Like Wagner, even in 1881 Nietzsche also still loved his former friend, to the extent of confessing to close friends that if Wagner invited him to the premiere of Parsifal he would go to Bayreuth. But Wagner was repulsed by the whole course taken by Nietzsche. It is worth looking into the matter a little because the case has certain similarities with my tortuous relationship with the American racial right, and there is something I would like to clarify about the Jewish question.

First, while Nietzsche wanted to push for a supranational European spirit, Wagner believed in the Germanic character as a culturising force.

Here, Wagner was right, while Nietzsche didn’t seem to realise that the ethnic factor is fundamental. American racialists, from this comparison, are closer to Nietzsche than to Wagner because, unlike German National Socialism, American anti-Nordicists imagine a supranational Europe, all united under the banner of a chimaera they call ‘white nationalism’. Sebastian Ronin, the Canadian critic of the American racial right, was right to say that all nationalism is ethno-nationalism (just as Wagner and later Hitler believed as far as Germany and Austria were concerned). It follows that it makes no sense to grant amnesty to the mudbloods of the Mediterranean who have ceased to be properly white (or the mudbloods of Portugal, Russia, etc.).

Secondly, this is precisely why Wagner saw the emergence of the Jewish element as a threat when Nietzsche fantasised that Jewish capital would finance his anti-Christian works! Wagner supported the anti-Semite Adolf Stöcker, of whom Nietzsche would go so far as to write years later, when he lost his mind, that he should be shot!

Today, the impossibility of the collective Aryan unconscious to make a political movement in which, say, Swedes and Sicilians feel perfectly brotherly to the extent of making both a single empire, gives the lie to the precepts of so-called white nationalism in the US. Although Richard Wagner knelt before the cross, he was right on this point and Nietzsche was wrong. The Germanic race does matter, as does a healthy anti-Semitism.

Crusade

against the Cross, 12

The documentary in the image above was made in 1999, not 2019, as the title says. In fact, when it was released and I watched it I was living in Manchester. It is worth watching it again for the images show many of the places we have been mentioning in this series. The dramatised images of Nietzsche’s dreadful loneliness remind me of ‘the lands of perpetual winter’ far north of the Wall in George R.R. Martin’s fiction.

______ 卐 ______

In the same year as the great premiere of the Bayreuth opera house, Nietzsche began writing Human, All Too Human. This work breaks with his previous style: for the first time, he experiments with short, penetrating aphorisms as an instrument for writing and communicating deep, incisive thought (he would write even more clearly in the last year of his lucid life).

Nietzsche applied for a leave of absence from the university due to illness. He took a year’s leave and went to Sorrento, one of the world’s beautiful coasts with a mild climate, where he spent the winter with Malwilda von Meysenburg, Paul Ree and other friends.

Ree was Nietzsche’s Jewish friend, which Cosima would eventually interpret as the betrayal of Judas, and that was the year of Nietzsche’s last conversation with Wagner. Although Nietzsche appreciated Ree, he always retained his reservations, so that with the Jew he never used the you of a friend. In German—as in Spanish—there is a fundamental difference that English lacks. Sie (usted in Spanish) is used when we speak to strangers and du (tú in Spanish) when we speak to people we know very well.

The sabbatical year showed Nietzsche that his ailments were not, as he perhaps believed, a psychosomatic conversion of his tedious academic activities as his acute attacks continued. The aetiology remained mysterious, and surely his malady had deeper roots than mere academic tedium, but Nietzsche still couldn’t find the right therapy.

The group of friends at the kindly Malwilda’s house read the freethinkers, Voltaire and Diderot, although Albert Brenner wrote with astonishment: ‘Rarely did the New Testament bring joy and comfort to unbelievers’. Epistolary, Malwilda confided to Cosima that Nietzsche disliked the Spanish writer Pedro Calderón de la Barca for his religiosity during the evening readings.

Elisabeth, like Cosima, had a better instinct for the Jewish question than her philosopher brother. For example, she was scandalised that her mother entered into an epistolary relationship with Ree. To my way of thinking, this means that intellectual sophistication should by no means be the yardstick for measuring the goodness of a philosophical system. Great philosophical cathedrals have been built on foundations of clay, and a plump and to some extent silly woman like Elisabeth could be much wiser in matters of Jewry than her sophisticated brother. This is a phenomenon I have encountered in life—a simple uncle turned out to be much wiser than another uncle with a high IQ—, but it was only until the third book of my autobiography that I matured in this matter, after decades of abject blindness.

In his sabbatical year in search of a cure, Nietzsche, already four years ill, began to discover that he was healthiest when he was alone. The first edition of his book, Human, All Too Human, was dedicated to Voltaire and its publication was planned for the centenary anniversary of his death on 30 May 1778 (in subsequent revised and expanded editions Nietzsche would remove the dedication to him). In early 1878 Nietzsche received Wagner’s libretto of Parsifal, and as a first cross-crossing of swords with his father figure, Nietzsche sent him Human, All Too Human.

Wagner, like Cosima, had become devout and saw himself as a descendant of Luther. Sending the new book without any accompanying words (perhaps only Nietzsche’s signature) was a major affront because the author criticised religious life and moral perceptions. The situation was made worse because Ernst Schmeitzner, who published both Wagner and Nietzsche, was threatened by Wagner that he would take the Bayreuther Blätter out of print. But Schmeitzner didn’t hold his tongue. He called the Wagners ‘hypocrites, they stink of church; Mrs Wagner goes to church, he goes to church too, though not much’ and added that ‘Wagner had knelt before the cross’. Wagner, for his part, considered it a terrible thing to take religion away from the German people.

This is where the paradoxes begin. Since he was seeking therapy for his ills, Nietzsche was doing himself a cathartic good by initiating a critique of Christianity—with which he had scores to settle from his cloistered time in Pforta—albeit in the form of aphorisms for the time being. But he was flatly wrong on the Jewish question, which he mentions in section 475 of Human, All Too Human. Here the musician was right that the Jews should be expelled from Germany, as Cosima admits in her diary: a position not uncommon among 19th-century patriots. (We can compare it to the situation in the United States today: rustic Christians like Nick Fuentes and company are wiser on the JQ than the more cultured or sophisticated atheists.)

Nietzsche, who after publication received a bust of Voltaire in the mail as a gift from a Parisian, feared he would be excommunicated in Bayreuth, as he let Peter Gast know, but thanks to the publication of his book he felt greatly rejuvenated. ‘If you felt what I feel since I have fixed my ideal of life’, Nietzsche wrote to Rhode, ‘the fresh, pure air of height… you might be very, very glad of your friend’. But to the German palate Human, All Too Human seemed harsher than that of the French Enlightenment, even to his friends.

Nietzsche was wrong in his new book to say that art should make way for science. In this Wagner was right, and our horrendously technological, scientistic century shows that the positivism of the new Nietzsche betrayed the earlier Nietzsche of The Birth of Tragedy. Wagner, for his part, wanted a return to Jesus Christ in a world without chemistry. He was right about chemistry (the fire of Prometheus shouldn’t have been given to the Europeans so prematurely, we see what would happen in the First World War!). But he was wrong about Jesus Christ. That’s why I said that this is where the great paradoxes begin as far as the split between Wagner and Nietzsche is concerned. Each was right on some points and wrong on others.

Cosima, in her correspondence with Elisabeth who wanted to mediate the conflict, wrote that she still loved the Nietzsche of former times, but that the author of Human, All Too Human was in an unhealthy state, and she ended her letter with the words: ‘May you soon show signs of life again, and may we keep our affection, despite all the trials… This is what your Cosima wishes you, in embracing you’.

Crusade

against the Cross, 11

Cosima Wagner was already a determined Christian. In Bayreuth, during the quiet winter evenings of 1875, she and her husband Richard immersed themselves in August Gfrörer’s Geschichte des Urchristenthums (History of Early Christianity). Although the Wagners were wise on the Jewish question, like today’s white nationalists, the couple simply ignored David Strauss’s book that had helped Nietzsche so much to take an important step on the road to apostasy.

Gfrörer still presented the Bible romantically, and the modern criticism of the New Testament didn’t affect the Wagner couple in the least. In Cosima’s diary, one can even guess a sort of concordat of this pair in matters of religion: Christian faith and Schopenhauer’s philosophy. (Can you see why I am repulsed by those first two hundred pages of Schopenhauer’s magnum opus, which a quarter of a century ago I bought in Manchester by the way, where the young philosopher presents the reader with the abstruse Kantian metaphysics—a neo-theology in my view?)

Richard Wagner would crown his life with a Christian work, Parsifal, about which I have written several posts on this site. The Parsifal project had been in Wagner’s mind since 1857, of which he wrote: ‘A warm, sunny Good Friday inspired me with Parsifal’, taken from the chivalric folklore about the mythical figure of Parzival. (Musically it is, of his operas, the one I like best: so much so that I used to listen to it when driving thanks to the compact discs of Georg Solti’s conducting the Vienna Philharmonic.)

Looking at the matter through Savitri Devi’s eyes, we discover that Wagner was ‘a man of his time’ and Nietzsche ‘a man against his time’. While the Wagners entertained celebrities in their home—the emperor’s son, several archdukes and beautiful ladies of high society—Nietzsche reluctantly followed his lessons.

For him, friendships were sacred. In Leipzig, he had befriended Heinrich Romundt (1845-1919), another classical philologist. Of his friends, Romundt was the closest to Nietzsche after Rhode and Gersdorff. But unlike Nietzsche, Romundt began to follow in Kant’s footsteps, got a professorship in Basel, and unexpectedly wanted to become a Catholic priest.

These were times when Pius IX had declared the Prussian anti-church law invalid! As one can guess from his correspondence with Rhode, Nietzsche was deeply hurt. Romundt had been a housemate in ‘the Basilian cave’, and had previously been in tune with these freethinkers.

After the loss of Romundt, as Gersdorff recounts in his letter of 17 April 1875, Nietzsche had a headache that lasted for thirty hours and repeated vomiting of bile. (It was the same nausea that the world gives me, but I avoid psychosomatic conversion by denouncing, in vindictive autobiographies,the people who have betrayed me.) Elisabeth, his sister, recounts that in the autumn of 1875, when they lived together, Nietzsche played the hymn to solitude on the piano almost every night. But in October Nietzsche met the musician Heinrich Köselitz, whom he nicknamed ‘Peter Gast’—literally Peter the Guest—and became close friends with him: a friendship that was to replace, in a way, the loss of Romundt.

Nietzsche found himself in a dilemma: mihi scribo, aliis vivo (do I write for myself, do I live for others?). Part of his being demanded that he belong to a group. On the other hand, the philosopher had already detected what, on this site, I have called the Christian question: the cause of German decline wasn’t only the Jewry that Wagner imagined. But if Nietzsche spoke his mind, he would suffer social ostracism. And if he didn’t say what he thought, the daimon that already lived in him would transmute into terrible ailments. He chose a third way: to begin to hint at what his inner daimon was whispering to him, albeit for the moment hermetically, in obscure aphorisms.

In one of the posthumous fragments from that period we can read a quotation from Voltaire, ‘Il faut dire la vérité et s’immoler’, to tell the truth is to immolate oneself. Stubbornly, he refused the Wagners’ generous invitations and went to meditate in the mountains and forests, on excursions where he felt freer. Above all, he had to avoid vomiting for hours on end that occurred without having eaten anything, and put aside the quackery cures of the time, such as those shameful enemas and leeches that a doctor had prescribed.

These were the times when the trumpets were already blowing for the opening of Bayreuth, and all his friends would gather there when the poor professor was still suffering from convulsions and stomach ailments: a morbus Wagneri. How could he proclaim the truth without aphorisms and in clear and transparent prose without self-immolation? Nietzsche wanted to surpass Wagner in stature, but that could only happen if another generation would recognise him as the originator of the new religion that was already brewing inside him. He was ‘a premature birth of a future not yet verified’, he would write. ‘Some are born posthumously’.

To be sure, Nietzsche had certain consolations in his existential loneliness. His time with Elisabeth brought back the happy memories of his early childhood, abruptly interrupted when he was cloistered for years in Schulpforta. He wanted, as he wrote to Gersdorff, ‘a simple home with a very orderly daily life’, although he also confessed to him that he had then spent the worst Christmas of his life.

In 1876 Nietzsche published the fourth of his Untimely Meditations, entitled Richard Wagner in Bayreuth. Thus the sick young man paid homage to the healthy old man, and to the Wagners he would send deluxe copies. While in search of freedom in Geneva, Nietzsche met the twenty-one-year-old Mathilde Trampedach. She was ‘blonde, slender, green-eyed and had a Renaissance figure’, writes Werner Ross. On 11 April Nietzsche made a sudden offer of marriage to her, whom he had met only five days earlier, but the nymph… refused.

In July the Bayreuth festivals began with The Ring of the Nibelung. Nietzsche was to arrive the following month.

Crusade

against the Cross, 7

Although 19th-century Basel was picturesque, it lacked hygiene to such an extent that a few years before Nietzsche lived there it had suffered a bout of cholera.

When he was already a respectable town professor, Nietzsche wore a top hat: the only one in Basel to do so. His friend Rhode remained faithful if distant; with Wagner, he continued his affectionate relationship, and the theologian Overbeck became his closest friend. It is difficult to imagine this Prussian reading passages from Mark Twain’s amusing novels in conversation with his friends, but this has come to light thanks to documents that have come into the possession of his biographers.

Although Nietzsche was already established and a member of the community, the Basilian professorship was to last only a decade. He didn’t like to be a teacher, although the exercises of the Greek tragedies were somewhat close to his interests. Nor was he interested in philological minutiae but in the intense spirit of ancient Greeks. He wanted the spirit of ancient Hellas to be reborn and distinguished from the sombre way in which its study was taught in the formal academy.

He also disliked that he had to appear daily before his students very early in the morning, in addition to preparing the countless hours of lectures and seminars. But he enjoyed the walks, the social life and the meals with his colleagues; he invited his students to his home—time and again he sought their warmth—and when he arrived home, a beautiful grand piano awaited him for his improvisations. With the anchorite image we got of him in his later years, it is hard to imagine him eating at his colleagues’ invitations, joking and even dancing.

But he was too shy to take the step Wagner strongly urged him to take: marriage. Werner Ross tells us that Nietzsche ‘has gone down in history as one of the few important men who has never even been known to have had a relationship with a woman. He was a special being: a fact that can be understood as a priestly renunciation for the sake of a mission that was to shake the world…’

Old-time friendships in Europe were deeper than ours. Curt Paul Janz observed that Nietzsche’s compositions for piano responded to the motto of friendship. Of Rohde, for example, Nietzsche writes, ‘of the best and rarest kind and faithful to me with touching love’. Rhode for his part wrote the following retrospective soliloquy in his diary of 1876: ‘Think of the golden gardens of happiness in which you lived while, in the spring of 1870, Nietzsche played for you the fragment from The Master Singers: “Morning Brightness”. Those were the best hours of my whole life’. And about the celebrated composer Nietzsche wrote about ‘the warmest and most agreeable nature of Wagner, of whom I want to say that he is the greatest genius and greatest man of our time, decidedly immeasurable!’ The group he had first formed with his Shopenhaurean friends mutated into a group that now deified a living man: Richard Wagner. Just as Bayreuth aimed to break with the way music was taught in Germany, Nietzsche wanted to break with the dead form in which philology was taught at the Academy.

Another of Nietzsche’s friends, Karl von Gersdorff, pictured above with Rohde, converted Nietzsche to vegetarianism; and Nietzsche, in turn, converted him to Wagnerianism. Although Gersdorff was in complete agreement with Wagner’s anti-Semitism and even viewed Mendelssohn’s music with contempt, Wagner was exasperated that Nietzsche wouldn’t eat meat when he invited him and even scolded him in front of Cosima. It is very significant to note that neither the Jupiterian Wagner nor the aristocratic Nietzsche said a word about the victims during La semaine sanglante (the bloody week) with which the French government repressed the Paris Commune.

When Nietzsche visited the Wagner house he brought toys bought in the Eisengasse in Basel for Cosima’s children, who saw the professor as a welcome playmate. Wagner himself began his letters with phrases like ‘Dearest Herr Friedrich…’ and had drawn up plans that, should he die prematurely, Nietzsche would be the tutor of his son Siegfried: named after the third opera of Wagner’s tetralogy inspired by pre-Christian mythology. This was Wagner’s fervent wish when Nietzsche was already twenty-eight years old, so, understandably, the academic activity to which he was chained was experienced as an ordeal.

By this time he had left philology behind and philosophy represented his real passion. But we must make it clear that Nietzsche didn’t have in mind the nonsense that, before him, had been written by all the so-called great philosophers (whom I have referred to on this site as neo-theologians). After all, none of them said anything influential about the Aryan race or the transvaluation of all Christian values. The ‘great’ philosophers had spent their lives discussing abstruse metaphysics and theories of knowledge but absolutely nothing relevant to our sacred words. Philosophy has been an immense Sahara of sterile discussions, and the fact that after so many centuries the philosophers haven’t even intuited what eventually motivated Adolf Hitler, is testimony to the frivolity of their activity.

At this point in his life, Nietzsche was already beginning to glimpse a prophetic mission. Many things were on his mind besides the reform of philology on Greco-Roman authors, and the majestic Aryan art that was to give birth to a New Renaissance as envisaged by Wagner, who now inaugurated it in Bayreuth: ideas that were swirling around in his head. We can imagine those times when the master already had white hair and the young professor sported a dark moustache, meetings presided over by the slender and refined Cosima: a woman who was to become a kind of muse for Nietzsche. Although, as a passionate admirer of Greece, one could imagine the professor travelling to Attica, the circle of the inveterate bachelor didn’t leave Naumburg, Leipzig, Lake Lucerne, Lake Geneva, the Swiss mountains and occasionally the Wagners’ house.

When the philosopher would mature, he would discover to his surprise that even Wagner had only been a way station on his spiritual odyssey.

Crusade

against the Cross, 5

A student philological organization in Leipzig. Nietzsche stands third from left facing Ernst Windisch, who is looking down.

The 19th century represented an awakening of a sector of the population in German-speaking countries to the Jewish question. As a man in tune with his times, Nietzsche would even write to his mother that he had finally found a brewery ‘where you don’t have to swallow melted butter and Jewish facades’. With his typical aristocratic tendency, the young Nietzsche considered all commerce unworthy, not just Jewish commerce. The proletariat was alien to him. He always believed that an uprising of the working class would destroy the world, so it had to be opposed.

For, having studied classical philology, Nietzsche had read directly the Greek writers of the ancient world, who weren’t infected by secular cross-worship in the sense of worshipping the crucified in turn. It was precisely the century in which Nietzsche lived that Doré, Dostoyevsky and Marx saw the horrors to which the Industrial Revolution had brought London and Manchester, times when ‘the crucified’ par excellence was the worker.

The decade before the photograph above, Count Gobineau had published his essay on the inequality of the human races, and Darwin on the origin of species. Those books written in French and English respectively ought to have been the best influences for the young philologist who knew so well the Greco-Roman classics and thus the scale of values before the advent of Judeo-Christianity. But Nietzsche would be impressed by what was then fashionable in German.

He read David Friedrich Strauss’ Life of Jesus. I have complained a lot on this site that much of the racial right is ignorant of the textual criticism that Germans have been making of the New Testament since the Enlightenment. The special edition of Strauss’ book that Nietzsche bought had been precisely the one that had appeared in German bookstores at a reasonable price for freethinkers of limited means. Nietzsche made the mistake of wanting to convey to a silly woman, Elisabeth, the reasons for his recent apostasy, now endorsed by the book in vogue at the time, while his sister replied to his letter confused and saddened by this typical turn of a 19th-century freethinking.

But Strauss wasn’t the most important influence on Nietzsche. In an antiquarian bookshop, he found Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation and began to leaf through it. He bought it and took it home to read. Later he would read Parerga and Paralipomena.

Except for Kant, Schopenhauer rejected the philosophers of classic German idealism, and showed Nietzsche what criticism of a nation’s culture is: university philosophy serves the State and the Church since it is from them that the philosopher receives his livelihood (Schopenhauer is somewhat hypocritical in this matter, since The World as Will and Representation begins with a very dull two hundred Kantian pages that could also fall under such category). The young Nietzsche had found an educator, but more than Schopenhauer’s doctrine, what was decisive was the attitude of the philosopher who not only opposed Hegel and company but presented himself to the world as a pessimistic and solitary hero.

That Nietzsche’s group worshipped the rebellious philosopher is evident from the fact that every year a group of Schopenhauerians celebrated his birth by drinking to the memory of their late master at a bacchanalian dinner. These were years in which the subject of Richard Wagner was also the order of the day, the talk of Leipzig. Werner Ross tells us: ‘The approach to Wagner is the most important event in Nietzsche’s entire biography. It surpasses in intensity and scope even his appointment as professor at the University of Basel’.

Wagner belonged to the section of Europeans aware of the Jewish problem and had written a book on the subject, but he needed fighters for his musical cause. Sophie Ritschl, the sister of Nietzsche’s teacher, took advantage of a whirlwind visit by Wagner to Leipzig to arrange an interview between Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche—a great honour for the latter. Everything seemed calculated to recruit the young genius to the Wagnerian cause!

On 8 November 1868 Nietzsche met Wagner, to whose music he was fully converted. He would never forget those days in which he felt himself treated as an equal of the greatest genius of the age.

But we must take into consideration the time we are talking about. When I saw Wagner’s first masterpiece, Tannhäuser, I was shocked that the Goddess Venus was defeated by invoking the voice of the Virgin Mary. While it is true that Wagner played with pre-Christian myths, he never broke with his Lutheran origins as drastically as Nietzsche would over the years. Nonetheless, when Nietzsche attended concerts playing the overtures to Tristan and The Master-Singers of Nuremberg, he wrote to his friend Rohde: ‘I cannot keep calm before this music: every fibre, every nerve stirs in me, and it is a long time since I have had such a feeling of rapture as when listening to the above overture’. (The same could be said of the impressions that the lad I was decades ago had!)

On 13 February 1869, the University of Basel appointed Nietzsche professor of classical philology: an astonishing case, for he was not even a doctor. This was mainly due to the influence of his teacher Ritschl, now indirectly involved in recruiting his pupil to the Wagnerian cause. On 23 March the University of Leipzig awarded Nietzsche a doctor’s degree, without examination or thesis, based on papers published in Ritschl’s Rheinisches Museum. On 13 April Nietzsche abandoned his German (Prussian) citizenship and became Swiss.

Wagner invited Nietzsche to ‘talk about music and philosophy’ and the young man naturally accepted. On 17 May he visited Wagner for the first time in Tribschen and was captivated. Wagner was ‘a fabulously lively and fiery man, who speaks very fast, is very witty and brings joy to a meeting’.

On 28 May Nietzsche gave the inaugural address of his professorship: Homer and Classical Philology and met the Renaissance scholar Jacob Burckhardt. In 1870 he continued his classes, lectures and philological studies, and in April he was appointed full professor: the year in which The Valkyrie was premiered in Munich. On 8 August he asked the university for permission to take part in the Franco-Prussian war, which was granted, but only as a nurse. Ironically, Nietzsche became seriously ill with dysentery. In October, he returned to Basel and began his important friendship with the theologian Franz Overbeck.

In 1871 Nietzsche began to write The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music: a plea for Wagner or proclamation that, through his music, the glorious days of ancient Greek values would return. (In this Nietzsche wasn’t wrong, as the next century Hitler would intuit; and the dream would have crystallised had he won the war.)

Early in 1872, The Birth of Tragedy was published, the book with which Nietzsche first introduced himself to the public at large. It was well received by his friends, but poorly received by the philologists in the profession. For this reason, Nietzsche even entertained the idea of leaving his chair in Basel to carry Wagner’s gospel as an itinerant preacher. The young philologist had become enchanted by the man who had been born in the same year as his father and, as Nietzsche himself would much later reveal in one of his letters of madness, also by Cosima Wagner.

In April Wagner left Tribschen, and on 22 May Nietzsche attended the laying of the foundation stone of the Wagnerian theatre in Bayreuth. These were the times of his greatest interest in Wagner, and he met Malwilda von Meysenburg through Wagnerian circles. At this time Nietzsche also composed the Manfried Meditation for piano four hands.

I read ‘Nietzsche’s Der Antichrist: Looking Back From the Year 100’ in late 1993, in a hard copy issued in the winter of 1988/1989: one of the back copies of Free Inquiry that arrived in the mail when I discovered that organisation of freethinkers.

I met the author, Robert Sheaffer, at the 1994 CSICOP conference. If memory serves, he wore sandals, was dressed casually and had a beard. Last year I exchanged some correspondence with him.

Sheaffer is anything but a Hitlerite. However, the article that I abridge below is perfect for understanding a central part of esoteric Hitlerism. I mean that Uncle Adolf’s anti-Christianity, which wasn’t revealed to the masses of Germans (hence the epithet ‘esoteric’), already had antecedents in Germany.

Sheaffer’s complete article can be read here. Red emphasis is mine:

______ 卐 ______

Secular humanists have not infrequently criticized the beliefs and practices of the Christian religion, and its harmful effects on civilization and culture. Unfortunately, their voice is seldom heard. The proponents of the Christian world-view vastly outnumber secularists both in number and in activity. While humanists wonder what they they can do to more effectively convey their criticisms of religion, most of them have never read, and indeed have barely even heard of, a book written exactly a century ago containing the most devastating and complete philosophical attack on Christian psychology, Christian beliefs and Christian values ever written: Nietzsche’s Der Antichrist.

1888 was the final productive year of the life of Friedrich Nietzsche, but it was a year of incredible activity. He wrote five books during a six-month period in the latter part of that year. After that, he wrote nothing. Nietzsche’s works of 1888 have not received enough attention, especially given the inclination of many to concentrate primarily on the flamboyant and somewhat confusing Also Spracht Zarathustra, a book of intricate allegories and parables which requires that one already understand the principal elements of Nietzschean thought in order to decipher its hidden relationships and meanings. Zarathustra will be clearer if it is read at the end of a course of study of Nietzsche, not at the beginning.

The first book of 1888 was The Case of Wagner, in which Nietzsche set forth his aesthetic and philosophical objections to the music and the writings of his former close friend Richard Wagner… Next came The Twilight of the Idols (in German, Die Gotzen-dammerung, an obvious parody of Wagner’s Die Gotterdammerung, “The Twilight of the Gods”), in which he criticizes romanticism, Schopenhauer’s pessimism, German culture, Socrates’ acceptance of death as a “healing” of the disease of life, Christianity, and a good many other things. Then, in September of 1888, Nietzsche wrote Der Antichrist.

Unlike Zarathustra, there can be no mistaking the language or the intention of Der Antichrist, a work of exceedingly clear prose and seldom-equalled polemics. Even today, the depth of Nietzsche’s contempt for everything Christianity represents will surprise and shock many people, and not only devout Christians. Unlike other critics of religion, Nietzsche’s attack extends beyond religious theology to Christian-derived concepts that have spread out far beyond their ecclesiastical origins, to the very core of the value-system of Western, Christianized society.

Der Antichrist begins with a warning that “This book belongs to the very few,” perhaps to no one yet living. Nietzsche hints that only those who have already mastered the obscure symbolism of his Zarathustra could appreciate this work. Warnings aside, he begins by sketching the idea of declining vs. ascending life and culture. An animal, a species, or an individual is “depraved” or “decadent” when it loses its instincts for that which sustains its life, and “prefers what is harmful to it.” Life itself presupposes an instinct for growth, for sustinence, for “the will to power”, the striving for some degree of control and mastery of one’s surroundings. Christianity sets itself up in opposition to those instincts, and hence Christianity is an expression of decadence, a negation of the will to life [Antichrist, section 6].

“Pity”, says Nietzsche, is “practical nihilism”, the contagion of suffering. By elevating pity to a value—indeed, the highest value—its depressive effects thwart those instincts which preserve life, establishing the deformed or the sick as the standard of value. [A 7] To Nietzsche, the rejection of pity did not proscribe generosity, magnanimity, or benevolence—indeed, the latter are mandated for “higher” types—; what is rejected is to allow the ill-constituted to define what is good. Nietzsche was not hostile to the sick—Zarathustra bids the sick to “become convalescents”, and expresses sympathetic understanding of their unhappy frame of mind [Z I 3]—but what he opposed was the use of the existence of sickness and other afflications to thereby claim “life is refuted” [Z I 9].

No doubt Nietzsche’s attack on “pity” was triggered in part by his revulsion against Wagner’s blatantly irrational opera Parsifal, in which the formerly irreligious Wagner returned once again to pious Christian themes. In Parsifal, a series of calamities occur because a once-holy knight succumbs to “sins of the flesh,” and it is prophesied that the situation cannot be remedied by any act of self-directed effort, but only by one “through pity made wise, a pure fool.” Nietzsche’s contempt for the limp Christianity in Parsifal and for “the pure fool” knew no bounds. The already-strained bond between the two men, who were once extremely close, was irreparably broken.

Nietzsche explains that the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer is, like Chrisitanity, decadent. Schopenhauer taught that since it is impossible to satisfy the desires of the will, one must ceaselessly renounce striving for what one wants, and become resigned to unhappiness. In the late 19th century Schopenhauer’s doctrines were extremely popular, especially among the Wagnerians. Wagner’s monumental Tristan and Isolde is an expression of Schopenhauerian nihilism, as the lovers sing of the impossibility of earthly happiness, and of their expected mystical union in the realm of “night” after their death. The opera closes with Isolde’s famous liebestod, or “love-death”, as she sings of a vision of her dead lover gloriously and mystically transfigured in the nether-regions, then dies to join him. Schopenhauer was hostile to life, says Nietzsche, “therefore pity became for him a virtue.” [A 7]

Nietzsche charges that Christianity denigrates the world around us as mere “appearance”, a position grounded in the philosophy of Plato and Kant, and hence invents a “completely fabricated” world of pure spirit. However, “pure spirit is pure lie,” and hence the theologian requires one to see the world falsely in order to remain a member in good standing in the religion. The Christian outlook was, he says, immensely bolstered against the attacks of the Enlightenment by Immanuel Kant, whose philosophy renders reality unknowable. (For Kant a virtue is something harmful to one’s life, a view Nietzsche could never accept. If you want to do something, Kant would say your action cannot possibly be virtuous; any action which contains an element of self-interest is by definition not virtuous.) Nietzsche summarizes, “anti-nature as instinct, German decadence as philosophy—that is Kant.” [A 8-11]

Nietzsche praises the skeptic (or “free spirit”) who rejects the priestly inversion of “true” and “untrue”. He says we skeptics no longer think of human life as having its origins in “spirit” or in “divinity”, but recognize the human race as a natural part of the animal kingdom… [A 12-14].

Returning to the theme of Christian doctrine as misrepresentation, Nietzsche charges that “in Christianity neither morality nor religion come into contact with reality at any point.” The religion deals with imaginary causes (such as God, soul, spirit) and imaginary effects (sin, grace, etc.), and the relationships between imaginary beings (God, souls, angels, etc.). It also has its own imaginary natural science (wholly anthropormorphic and non-naturalistic), an imaginary human psychology (based on repentance, temptation, etc.), as well as an imaginary teleology (apocalypse, the kingdom of God, etc.). Nietzsche concludes that this “entire fictional world has its roots in the hatred of the natural” world, a hatred which reveals its origin. For “who alone has reason to lie himself out of actuality? He who suffers from it” [A 15]. Here is the proof which convinced Nietzsche that Christianity is not only decadent in its origins, but rotten to its very core: no one reasonably satisfied with his own mind and abilities would wish to see the real world replaced with a lie.

Comparing religions, Nietzsche came to the conclusion that in a healthy society, its gods represent the highest ideals, aspirations, and sense of competence of that people. For example, Zeus and Apollo were obviously powerful ideals for Greek society, an image of the mightiest mortals projected into the heavens. Such gods are fully human, and display human strengths and weaknesses alike. The Christian God, however, shows none of the normal human attributes and appetites. It is unthinkable for this God to desire sex, food, or even openly display revengefulness (as did the Greek gods). Such a God is clearly emaciated, sick, castrated, a reflection of the people who invented him. If a god symbolizes a people’s perceived sense of impotence, he will degenerate into being merely “good” (an idealized image of the kind master, as desired by all slaves), void of all genuinely human attributes. The Christian God represents the “divinity of decadence,” the reduction of the divine into a God who is the contradiction of life. Those impotent people who created such a God in their own image do not wish to call themselves “the weak,” so they call themselves “the good.” [A 16-19].

Comparing religions, Nietzsche came to the conclusion that in a healthy society, its gods represent the highest ideals, aspirations, and sense of competence of that people. For example, Zeus and Apollo were obviously powerful ideals for Greek society, an image of the mightiest mortals projected into the heavens. Such gods are fully human, and display human strengths and weaknesses alike. The Christian God, however, shows none of the normal human attributes and appetites. It is unthinkable for this God to desire sex, food, or even openly display revengefulness (as did the Greek gods). Such a God is clearly emaciated, sick, castrated, a reflection of the people who invented him. If a god symbolizes a people’s perceived sense of impotence, he will degenerate into being merely “good” (an idealized image of the kind master, as desired by all slaves), void of all genuinely human attributes. The Christian God represents the “divinity of decadence,” the reduction of the divine into a God who is the contradiction of life. Those impotent people who created such a God in their own image do not wish to call themselves “the weak,” so they call themselves “the good.” [A 16-19].

Nietzsche next compares Christianity to Buddhism. Both, he says, are religions of decadence, but Buddhism is a hundred times wiser and more realistic. Buddha does not demand prayer or aesceticism, demanding instead ideas which produce repose or cheerfulness. Buddhism, he says, is most at home in the higher and learned classes, while Christianity represents the revengeful instincts of the subjugated and the oppressed. Buddhism promotes hygiene, while Christianity repudiates hygiene as sensuality. Buddhism is a religion for mature, older cultures, for persons grown kindly and gentle—Europe is not nearly ripe for Buddhism. Christianity, however, tamed uncivilized barbarians, needing to subjugate wild “beasts of prey,” who cannot control their own “will to power.” The way it did so was to make them sick, making them thereby too weak to follow their destructive instincts. Thus Buddhism is a religion suited to the decadence and fatigue of an ancient civilization, while Christianity was useful in taming barbarians, where no civilization had existed at all. [A 20-22].

Nietzsche next emphasises Christianity’s origin in Judaism, and its continuity with Jewish theology. He was fond of pointing out the essential Jewishness of Christianity as a foil to the anti-Semites he so despised, effectively taunting them, “you who hate the Jews so, why did you adopt their religion?”. It was the Jews, he asserts, who first falsified the inner and outer world with a metaphysically complete anti-world, one in which natural causality plays no role. (One might of course object that such a concept considerably predates Old Testament times.) The Jews did this, however, not out of hatred or decadence, but for a good reason: to survive. The Jews’ will for survival is, he asserts, the most powerful “vital energy” in history, and Nietzsche admired those who struggle mightily to survive and prevail. As captives and slaves of more powerful civilizations—the Babylonians and the Egyptians—the Jews shrewdly allied themselves with every “decadence” movement, with everything that weakens a society, not because they were decadent themselves, but in order to weaken their oppressors. Thus, Nietzsche views the Jews as shrewdly inculcating guilt, resentment, and other values hostile to life among their oppressors as a form of ideological germ warfare, taking care not to become fully infected themselves. This technique was ultimately successful in defeating stronger parties—Babylonians, Egyptians, and Romans—by in essence making them “sick,” and hence less powerful. (The Romans, of course, succumbed to the Christian form of Judaism, in this view.) This parallels St. Augustine’s comment, quoting Seneca, that the Jews “have imposed their customs on their conquerors.” [A 23-26; De Civitate Dei VI 11]

“On a soil falsified in this way, where all nature, all natural value, all reality had the profoundest instincts of the ruling class against it, there arose Christianity, a form of mortal hostility to reality as yet unsurpassed.” The revolt led by Jesus was not primarily religious, says Nietzsche, but was instead a secular revolt against the power of the Jewish religious authorities. The very dregs of Jewish society rose up in “revolt against ‘the good and the just’, against ‘the saints of Israel’.” This was the political crime of Jesus, a crime of which he was surely guilty, and for which he was crucified. Nietzsche examines the psychology of Jesus, as is best possible from the Biblical accounts, and detects a profound sense of withdrawl: resist not evil, the kingdom of God is within you, etc. He sees parallels in the psychology of Christ not with some hero, but with Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. (Dostoyevsky is not mentioned here by name, but we know from other sources that this is the “idiot” Nietzsche had in mind.)

Nietzsche deduces that the earliest Christians sought to retreat into a state of extreme withdrawl from “the world”, undisturbed by reality of any kind. They rejected all strong feelings, favorable or otherwise. Their fear of pain, even in infinitely small amounts, “cannot end otherwise than in a religion of love.” Thus Nietzsche sees early Christianity as promoting an extremely dysfunctional state resembling autism, a defense mechanism for those who cannot deal with reality. Noting Christianity’s claims to deny the world, and its stand in opposition to every active virtue, Nietzsche asks how can any person of dignity and accomplishment not feel ashamed to be called a Christian? [A 27-30; 38]…

By placing the center of life outside of life, in “the beyond”, Nietzsche says we deprive life of any focus or center whatsoever. The invention of the immortal soul automatically levels all rank in society: “‘immortality’ conceded to every Peter and Paul has so far been greatest, the most malignant attempt to assassinate noble humanity”. Thus “little prigs and three-quarter madmen may have the conceit that the laws of nature are constantly broken for their sakes,” thereby obiliterating all distinctions grounded in merit, knowledge or accomplishment. Christianity owes its success to this flattering of the vanity of “all the failures, all the rebellious-minded, all the less favored, the whole scum and refuse of humanity who were thus won over to it.” For Christianity is “a revolt of everything that crawls upon the ground directed against that which is elevated: the gospel of the ‘lowly’ makes low.” Here we clearly see Nietzsche’s repudiation of Christianity’s attitudes as well as its theology: as he pointedly noted in Ecce Homo, “no one hitherto has felt Christian morality beneath him”. All others saw it as an unattainable ideal. [A 43; EH 4 (“Why I Am a Fatality”) 8] Pre-Christian thinkers did not, of course, see poverty as suggestive of virtue, but rather of its absence. One point Nietzsche was unable to either forgive or forget was that the enemies of the early Christians were “the intelligent ones”, persons far more civilized, erudite, and accomplished than themselves, people who Nietzsche felt more fit to rule than the Christians.

Nietzsche sees the Gospels as proof that corruption of Christ’s ideals had already occurred in those early Christian communities. They say “Judge Not!”, then send to Hell anyone who stands in their way. Arrogance poses as modesty. He explains how the Gospel typifies the morality of ressentiment ( a French term Nietzsche used in his German texts), a spirit of vindictiveness and covert revengefulness common among those who are seething with a sense of their own impotence, and hence must hide their desire for vengeance. “Paul was the greatest of all apostles of revenge,” writes Nietzsche [A 44-45]…

At this point, Nietzsche advises the reader to “put on gloves” when reading the New Testament, because one is in proximity to “so much uncleanliness.” It is impossible, he says, to read the New Testament without feeling a partiality for everything it attacks. The Scribes and the Pharisees must have had considerable merit, to have been attacked by the rabble in such a manner. Everything the first Christians hate has value, for theirs is the unthinking hatred of the rabble for everyone who is not a wretched failure like themselves. Nietzsche sees Christianity’s origins in what Marxists would call “class warfare,” and sides with those possessing learning and self-discipline against those having neither. [A 46].

He next turns to a point essential for the understanding of Nietzschean thought: the inevitability of a “warfare” between Christianity and science. Because Christianity is a religion which has no contact with reality at any point, it “must naturally be a mortal enemy of ‘the wisdom of the world,’ that is to say, of science.” Here “science” is not to be understood as merely the physical sciences, but as any rigorous and disciplined field of human knowledge, all of which are potentially threats to Christian dogma. Hence Christianity must calumniate the “disciplining of the intellect” and intellectual freedom, bringing all organized secular knowledge into disrepute; for “Paul understood the need for the lie, for faith.” Nietzsche refers to the Genesis fable of Eve’s temptation, asking whether its significance has really been understood: “God’s mortal terror of science”? The priest perceives only one great danger: the human intellect unfettered. Continuing the metaphor of science as eating from the tree of knowledge:

Science makes godlike—it is all over with priests and gods when man becomes scientific. Moral: science is the forbidden as such—it alone is forbidden. Science is the first sin, the original sin. This alone is morality “Thou shalt not know”—the rest follows.

The priest invents and encourages every kind of suffering and distress so that man may not have the opportunity to become scientific, which requires a considerable degree of free time, health, and an outlook of confident positivism. Thus, the religious authorities work hard to make and keep people feeling sinful, unworthy, and unhappy. [A 47-49]

In previous works, Nietzsche had emphasised the necessity of struggling hard to uncover truth, of preferring an unpleasant truth to an agreeable delusion. [The Gay Science 344; Beyond Good and Evil 39] Consequently, he sees another reason for being suspicious of Christianity in its notion that “faith makes blessed,” that is, creates a state of pleasure in harmony with God. He re-iterates that whether or not a doctrine is comforting tells us nothing about its truth. Nor does the willingness of martyrs to suffer and die for a belief constitute any proof of veracity, suggesting that a visit to a madhouse will suffice to demonstrate the fallaciousness of such arguments. Martyrdoms have, in fact, been a great misfortune throughout history because “they have seduced” us into questionable doctrines. “Blood is the worst witness of truth”. [A 50-51, 53]

Christianity, says Nietzsche, needs sickness as much as Hellenism needed health. (To understand this point, compare a Greek statue of a tall, handsome, naked God with a Christian religious image of an unhygenic, slovenly figure suffering greatly.) One does not “convert” to Christianity, but rather one must be made “sick enough” for it. The Christian movement was, from its beginning, “a collective movement of outcast and refuse elements of every kind,” seeking to come to power through it. “In hoc signo decadence conquered.” Christianity also stands in opposition to intellectual, as well as physical, health. To doubt becomes sin. Nietzsche defines faith as “not wanting to know what is true,” a description which strikes me as stunning, and quite exact. [A 51-52]…

Christianity, says Nietzsche, needs sickness as much as Hellenism needed health. (To understand this point, compare a Greek statue of a tall, handsome, naked God with a Christian religious image of an unhygenic, slovenly figure suffering greatly.) One does not “convert” to Christianity, but rather one must be made “sick enough” for it. The Christian movement was, from its beginning, “a collective movement of outcast and refuse elements of every kind,” seeking to come to power through it. “In hoc signo decadence conquered.” Christianity also stands in opposition to intellectual, as well as physical, health. To doubt becomes sin. Nietzsche defines faith as “not wanting to know what is true,” a description which strikes me as stunning, and quite exact. [A 51-52]…

Nietzsche now turns to consider why the lie is told. Once again, Christian teachings are compared to those of another religion, that of Manu, “an incomparably spiritual and superior work.” Unlike the Bible, the Law-Book of Manu is a means for the “noble orders” to keep the mob under control. Here, human love, sensuality, and procreation are treated not with revulsion, but with reverence and respect. After a people acquires a certain experience and success in life, its most “enlightened,” most “reflective and far-sighted class” sets down a law summarizing its formula for success in life, which is represented as a revelation from a deity, for it to be accepted unquestioningly. Such a set of rules is a formula for obtaining “happiness, beauty, benevolence on earth.” This aristocratic group considers “the hard task a privilege… life becomes harder and harder as it approaches the heights—the coldness increases, the responsibility increases.” All ugly manners and pessimism are below such leaders: “indignation is the privilege of the Chandala” (Indian untouchable). What is bad? “Everything that proceeds from weakness, from revengefulness.” [A 57]

Thus Nietzsche holds that the purpose for the lie of “faith” makes a great difference in the effect it will have on society. Do the priests lie in order to preserve (as in the book of Manu, and presumably Greek myth), or to destroy (as in Christianity)? Thus Christians and socialist Anarchists are identical in their instincts: both seek solely to destroy. The Roman civilization was a magnificent edifice for the prosperity and advancement of life, “the most magnificent form of organization under difficult circumstances which has yet been achieved”, which Christianity sought to destroy because life prospered within it. These “holy anarchists” made it a religious duty to “destroy the world”, which actually meant, “destroy the Roman Empire”. They weakened the Empire so much that even “Teutons and other louts” could conquer it. Christianity was the “vampire” of the Roman Empire. These “stealthy vermin,” shrouded in night and fog, crept up and “sucked out” from everyone “the seriousness for true things and any instinct for reality.” Christianity moved truth into “the beyond”, and “with the beyond one kills life.”

Before charging Nietzsche with possibly irresponsible invective, compare the above with Gibbon’s summary of the role of Christianity in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of a military spirit were buried in the cloister: a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers’ pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity.

On the positive side, Gibbon notes that even though Christianity clearly hastened the demise of Rome, it “mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors”. This would seem to parallel Nietzsche’s view that Christianity seeks to control the uncivilized not by teaching them the self-discipline needed to control their own impulses, but by making them too “sick” to do a great deal of harm. [A 58; Gibbon, Chapter 38 ]

“The whole labor of the Ancient World in vain!”: thus does Nietzsche overstate the magnitude of the calamity. (Our civilization’s heritage from classical antiquity is obviously far from nothing!). Nonetheless, no one who prefers civilization to barbarism can be indifferent to the point here raised. Nietzsche emphasises that the foundations for a scholarly culture, for science, medicine, philosophy, and art, had all been magnificently laid in antiquity, only to be destroyed by the advent of Christianity. Today, he says, we have certainly made great progress, but each of us still retains bad Christian habits and instincts which we must work hard to overcome. Two thousand years ago, we had acquired that clear eye for reality, patience, attention to detail, seriousness in even small matters—and it was not obtained by “drill” or from habit, but flowed naturally from a civilized instinct. All this was lost! And it was not lost to some natural disaster or destroyed by “Teutons and other buffalos” (Nietzsche’s contempt for German nationalism and militarism knew no bounds!) but it was “ruined by cunning, stealthy, invisible, anemic vampires. Not vanquished-merely drained. Hidden vengefulness, petty envy become master.” Everything that was miserable and filled with bad feelings about itself came to the top at once. [A 59]…

The meaning and significance of the Renaissance is considered in this next-to-last section of Der Antichrist. “The Germans have cheated Europe out of the last great cultural harvest which Europe could still have brought home—that of the Renaissance.” Nietzsche views the Renaissance as “the revaluation of Christian values,” that is, the repudiation of life-denying Christian values and their replacement with secular values which emphasise art, culture, learning, and so on. With the Renaissance in Italy, Christianity was being repudiated at its very seat. “Christianity no longer sat on the Papal throne! Life sat there instead!”

Nietzsche envisions the immortal roar of laughter that would have risen up from the gods on Mount Olympus had Cesare Borgia actually succeeded in his ruthless quest to become Pope. (The notorious murderer and poisoner Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, spread his power ruthlessly across Italy. Father and son appointed or poisoned Cardinals as needed to position the son for election as the next Pope. However, the plan went awry when they accidentally tasted some wine that had been “prepared” to rid themselves of a wealthy cardinal! The father died, and the son became gravely ill, and was hence in no position to coerce the selection of his father’s successor.)

Nietzsche envisions the immortal roar of laughter that would have risen up from the gods on Mount Olympus had Cesare Borgia actually succeeded in his ruthless quest to become Pope. (The notorious murderer and poisoner Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, spread his power ruthlessly across Italy. Father and son appointed or poisoned Cardinals as needed to position the son for election as the next Pope. However, the plan went awry when they accidentally tasted some wine that had been “prepared” to rid themselves of a wealthy cardinal! The father died, and the son became gravely ill, and was hence in no position to coerce the selection of his father’s successor.)

Nietzsche laments that this great world-historical event—life returning to Western culture—was ultimately undone by the work of “a German monk,” Martin Luther, who harbored the vengeful instincts of “a failed priest.” Through Luther’s Reformation, and Catholicism’s answer to it, the Counter-Reformation, Christianity was restored. [A 60] One might be tempted to dismiss Nietzsche’s dramatic interpretation of the Renaissance, except that his view meshes with that of Jacob Burckhardt, the single most influential historian of Renaissance civilization who ever lived. Burckhardt’s monumental work, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), has influenced the study of that period as much as Gibbon’s Decline and Fall did that of ancient Rome. Neitzsche and Burckhardt were colleagues at the University of Basle, and friends as well. In the first section of his Civilization, Burchkardt writes that the greatest danger ever faced by the Papacy was its secularization during the Renaissance.

The danger that came from within, from the Popes themselves and their nipoti (relativies, “nepotism”), was set aside for centuries by the German Reformation… The moral salvation of the papacy was due to its mortal enemies… Without the Reformation—if indeed it is possible to think it away—the whole ecclesiastical state would have passed into secular hands long ago.

Pope Julius II, powerfully anti-Borgia, was “the savior of the Papacy,” who put an end to the practice of the buying and selling of Church positions. However, the Counter-Reformation “annihlated the higher spiritual life of the people,” according to Burckhardt. Nietzsche would have said this was because they had become Christian once again.

The final section of Der Antichrist contains “the most terrible charge” against the Christian Church that “any prosecutor has ever uttered… I call Christianity the one great curse, the one great intrinsic depravity, the one great instinct for revenge for which no expedient is sufficiently poisonous, secret, subterranean, petty—I call it the one immortal blemish of mankind.” Nietzsche suggests that instead of calculating time from the “unlucky day” on which this “fatality” arose, time should be measured instead from its last day: “from today.” [A 62].

Needless to say, Nietzsche’s Der Antichrist did not prove to be the dagger in the heart of Christianity he hoped it would. After finishing this work (which was not actually published until 1895), Nietzsche wrote Ecce Homo, a philosophical autobiography, in which we first see signs of the self-aggrandizing delusions which were to characterize his incipient mental collapse. The final major work of 1888 was Nietzsche Contra Wagner, containing more polemics against the “decadence” and anti-Semetism of Wagner’s followers, much of which was taken from his earlier published works. Nietzsche’s philosophical writings end there, in the closing weeks of 1888. No doubt the breakdown which followed was hastened by the frantic pace of work during that period. Living in Turin, Italy, alone as was his habit, he continued to send letters to his family and friends.

Early in January, 1889, Nietzsche collapsed on the street in Turin. Some local people helped him back to his room, and he was soon alone again. On January 6 he sent letters to Burckhardt and to Franz Overbeck, another friend and colleague at the University of Basle, displaying obvious signs of insanity. Burckhardt, quite concerned, consulted Overbeck, who was soon on a train headed for Turin to assist his friend. Overbeck brought Nietzsche back to his mother in Germany. He was placed in an institution for a few months, and was then released to the care of his family, where he lived another eleven years as an invalid. Nietzsche actually died twice: his mind died in 1889, while his body lived on helplessly until 1900…

If Nietzsche’s polemically effective suggestion had been adopted—to begin counting time from the start of Christianity’s presumed demise, the writing of Der Antichrist—then I would now be writing these words in the year 100 P.C., the hundredth year of the post-Christian era. It would obviously be premature to expect such a calendar to gain widespread acceptance today! Yet the failure of Nietzsche’s impossibly high expectations should not cause us to overlook the significance of this monumental work, with its searing insights into the psychology of Christian belief. All those who wish not to renounce life but to affirm it, all who seek to proclaim a triumphant “yes” to human prosperity, knowledge, and happiness, will find in Der Antichrist invaluable insights on how those goals can be achieved—and on what stands on the way of them.

Notes:

There are two excellent English translations of Der Antichrist readily available, one by R. J. Hollingdale (Penguin Classics, 1968), the other by Walter Kaufmann (in Kaufmann’s The Portable Nietzsche, Penguin Books, 1978).

Dialectic synthesis

On the eleventh of this month, I said that what moved me to present the story of Richard Wagner’s tetralogy was to try to elucidate a little more of Savitri Devi’s point of view, insofar as I consider her book, together with my footnotes, to be a kind of manifesto of The West’s Darkest Hour.

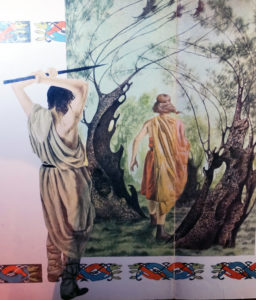

I’m still four entries short of completing the tetralogy’s story (the penultimate, which deals with Siegfried’s death, will be the longest in the series) according to the Argentine publisher who summarised the story when I was a child. I’ve already taken several images from those illustrated booklets, as can be seen here, here, here and here. But I would like, at once, to put down in writing some of my conclusions even before I finish translating the series.

I have just reviewed my thick biographical volumes on Friedrich Nietzsche, written by two German scholars. Nietzsche apparently lost his sanity on the last day of 1888. It is fascinating to note that his last essay before losing his mind was ‘Nietzsche contra Wagner’. Recall that, years before, Wagner and Nietzsche had been great friends. These are my conclusions:

Wagner was absolutely right to consider Jewry a parasite; and the later Nietzsche, i.e. the Nietzsche of the last months of 1888, was absolutely wrong to hate anti-Semites. But Wagner was completely wrong in believing that it was enough to baptise the Jews to make them good. For example, when for his last opera, Parsifal, he was assigned a Jewish conductor, Wagner rebelled and said that he would only accept him if he was first baptised. Such a stance reminds me of the American E. Michael Jones, although Jones is a Catholic and Wagner was a Protestant.

On the other hand, Nietzsche was right to condemn Judeo-Christianity as the key factor in the decline of Aryan culture, as we can see in this quote written before his upheaval. Precisely because of this, Nietzsche began to distance himself from Wagner when he began to see that the composer was making concessions to Christian morality.

The dialectic synthesis, so to speak, between the grave rights and grave wrongs of both Wagner and Nietzsche, provides a picture in which the contradictions of both are resolved. Resolving the contradictions of both positions is what I attempt on this site: unlike the latter Nietzsche we must be aware of the JQ, but, also, unlike Wagner we must be aware of the CQ.

All this has to do with Savitri’s book because, if our understanding of the cause of the dark hour isn’t perfect (Savitri wasn’t as anti-Christian as Nietzsche), we won’t be able to save the Aryan man. We will end up deceived by unscrupulous rascals like those who deceived Siegfried and eventually killed him. There is more I would like to say about the Wagnerian tetralogy but for tonight the above is enough.

(Incidentally, this image also appears in one of the booklets I used to leaf through as a child, which I still have in my library after so many decades of leafing through them for the first time.)

Wagner

In announcing the abridged translation of Savitri Devi’s Souvenirs et réflexions d’une Aryenne, I wrote:

There are many things I’d like to comment on now that, by editing it severely to make it more readable (the French sentences Savitri uses were too long and the thread of discussion was lost), I came to grasp her philosophy.

The first thing that occurs to me, in addition to the preface I added to this translation, is to complement her philosophy by translating (1) an essay originally published in the webzine Evropa Soberana on what Hinduism says about the darkest hour of the Abendland (the West), and (2) a simplified version of the text of Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung. That will round off a bit the content of this splendid book by Savitri which, as I say in the ‘Editor’s Preface’, helps us to finish crossing the Rubicon (instead of getting stuck inside the river, as those on the racial right are stuck today).

The first clause has already been fulfilled here, here and here.

Now I’ll fulfil the second: to present the general idea of Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung to fill in the questions left open in Savitri’s philosophy. I do this because I have noticed that neo-Nazis use swastikas and other Nazi paraphernalia but are generally ignorant of the art that the Führer loved.

On the internet, I haven’t found an English abbreviation of The Ring of the Nibelung at a level that a Wagner neophyte could understand. So in the next entry, I will start translating Wagner’s story from an illustrated collection I used to leaf through when I was a child. This abridged translation of Wagner’s tetralogy was published in Fabulandia: something analogous to an illustrated edition of Grimms’ Fairy Tales in collectable instalments, published by Editorial Codex of Argentina in the 1960s.

Although I watched with interest the complete tetralogy on the small screen, it is too long and complex and requires a literary abridgement, such as this one undertaken by the Argentines of the last century, for the neophyte to understand Wagner’s magnum opus.

While I translate the first fascicle of the tetralogy the visitor could read our 2011 post, ‘Wagner’s wisdom’. It should be remembered that the author of that essay, a German who published articles in Kevin MacDonald’s webzine under the pseudonym Michael Colhaze, eventually asked MacDonald to delete all his articles presumably because he could be targeted by German thoughtpolice. Fortunately I saved his article, which I re-titled ‘Wagner’s wisdom’, in the old incarnation of The West’s Darkest Hour.

The Master-Singers of Nuremberg

Wow, I have just listened, complete, in four nights as it lasts over four hours, The Master-Singers of Nuremberg (original title, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg): an opera in three acts with music and libretto in German by Richard Wagner. I didn’t plan to post anything after I finished watching it but Hans Sachs’ final speech at the end of Act III—in fact, the culmination of the opera—made a huge impression on me:

Beware! Evil tricks threaten us; if the German people and kingdom should one day decay under a false, foreign rule, soon no prince would understand his people; and foreign mists with foreign vanities they would plant in our German land; what is German and true none would know, if it did not live in the honour of German masters. Therefore I say to you: honour your German masters, then you will conjure up good spirits! And if you favour their endeavours, even if the Holy Roman Empire should dissolve in mist, for us there would yet remain holy German Art!

After WWII the words I italicised above (‘if the German people and kingdom should one day decay under a false, foreign rule, soon no prince would understand his people’) became prophetic. But if Wagner’s poetry is right, as long as the German people do not break contact with the soul of their race,[1] they can still be saved.

A small piece of advice for those who want to be introduced to Wagner’s art.

Watching his operas on YouTube is not recommended: art loses most of its numinousness. You have to go to the fancy opera house with all the ritual that goes with it and see the characters in their live costumes. I had to watch it on YouTube because I hadn’t seen Die Meistersinger and could not afford the trip to Bayreuth. (Besides, in recent years those in charge of Wagner’s legacy have betrayed the theatrical staging.)

I would suggest that the initiate simply listen, repeatedly, the majestic overture to Die Meistersinger and the long, elegiac prelude to Act III that shows a pensive Sachs in the privacy of his home.

If this truly Aryan music has been assimilated, you could watch the final half-hour of the interpretation I watched tonight, where Sachs delivers his speech to his beloved people of Nuremberg. The problem is that the subtitles of this interpretation are in French and Spanish. I could understand the plot, but not everyone knows those languages.

__________

[1] Speaking of saving the German spirit from the foreign forces of occupation, Savitri’s book, which I am proofreading, will not be ready until February.