against the Cross, 7

Although 19th-century Basel was picturesque, it lacked hygiene to such an extent that a few years before Nietzsche lived there it had suffered a bout of cholera.

When he was already a respectable town professor, Nietzsche wore a top hat: the only one in Basel to do so. His friend Rhode remained faithful if distant; with Wagner, he continued his affectionate relationship, and the theologian Overbeck became his closest friend. It is difficult to imagine this Prussian reading passages from Mark Twain’s amusing novels in conversation with his friends, but this has come to light thanks to documents that have come into the possession of his biographers.

Although Nietzsche was already established and a member of the community, the Basilian professorship was to last only a decade. He didn’t like to be a teacher, although the exercises of the Greek tragedies were somewhat close to his interests. Nor was he interested in philological minutiae but in the intense spirit of ancient Greeks. He wanted the spirit of ancient Hellas to be reborn and distinguished from the sombre way in which its study was taught in the formal academy.

He also disliked that he had to appear daily before his students very early in the morning, in addition to preparing the countless hours of lectures and seminars. But he enjoyed the walks, the social life and the meals with his colleagues; he invited his students to his home—time and again he sought their warmth—and when he arrived home, a beautiful grand piano awaited him for his improvisations. With the anchorite image we got of him in his later years, it is hard to imagine him eating at his colleagues’ invitations, joking and even dancing.

But he was too shy to take the step Wagner strongly urged him to take: marriage. Werner Ross tells us that Nietzsche ‘has gone down in history as one of the few important men who has never even been known to have had a relationship with a woman. He was a special being: a fact that can be understood as a priestly renunciation for the sake of a mission that was to shake the world…’

Old-time friendships in Europe were deeper than ours. Curt Paul Janz observed that Nietzsche’s compositions for piano responded to the motto of friendship. Of Rohde, for example, Nietzsche writes, ‘of the best and rarest kind and faithful to me with touching love’. Rhode for his part wrote the following retrospective soliloquy in his diary of 1876: ‘Think of the golden gardens of happiness in which you lived while, in the spring of 1870, Nietzsche played for you the fragment from The Master Singers: “Morning Brightness”. Those were the best hours of my whole life’. And about the celebrated composer Nietzsche wrote about ‘the warmest and most agreeable nature of Wagner, of whom I want to say that he is the greatest genius and greatest man of our time, decidedly immeasurable!’ The group he had first formed with his Shopenhaurean friends mutated into a group that now deified a living man: Richard Wagner. Just as Bayreuth aimed to break with the way music was taught in Germany, Nietzsche wanted to break with the dead form in which philology was taught at the Academy.

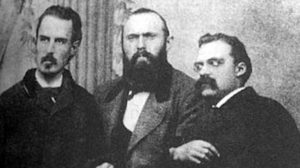

Another of Nietzsche’s friends, Karl von Gersdorff, pictured above with Rohde, converted Nietzsche to vegetarianism; and Nietzsche, in turn, converted him to Wagnerianism. Although Gersdorff was in complete agreement with Wagner’s anti-Semitism and even viewed Mendelssohn’s music with contempt, Wagner was exasperated that Nietzsche wouldn’t eat meat when he invited him and even scolded him in front of Cosima. It is very significant to note that neither the Jupiterian Wagner nor the aristocratic Nietzsche said a word about the victims during La semaine sanglante (the bloody week) with which the French government repressed the Paris Commune.

When Nietzsche visited the Wagner house he brought toys bought in the Eisengasse in Basel for Cosima’s children, who saw the professor as a welcome playmate. Wagner himself began his letters with phrases like ‘Dearest Herr Friedrich…’ and had drawn up plans that, should he die prematurely, Nietzsche would be the tutor of his son Siegfried: named after the third opera of Wagner’s tetralogy inspired by pre-Christian mythology. This was Wagner’s fervent wish when Nietzsche was already twenty-eight years old, so, understandably, the academic activity to which he was chained was experienced as an ordeal.

By this time he had left philology behind and philosophy represented his real passion. But we must make it clear that Nietzsche didn’t have in mind the nonsense that, before him, had been written by all the so-called great philosophers (whom I have referred to on this site as neo-theologians). After all, none of them said anything influential about the Aryan race or the transvaluation of all Christian values. The ‘great’ philosophers had spent their lives discussing abstruse metaphysics and theories of knowledge but absolutely nothing relevant to our sacred words. Philosophy has been an immense Sahara of sterile discussions, and the fact that after so many centuries the philosophers haven’t even intuited what eventually motivated Adolf Hitler, is testimony to the frivolity of their activity.

At this point in his life, Nietzsche was already beginning to glimpse a prophetic mission. Many things were on his mind besides the reform of philology on Greco-Roman authors, and the majestic Aryan art that was to give birth to a New Renaissance as envisaged by Wagner, who now inaugurated it in Bayreuth: ideas that were swirling around in his head. We can imagine those times when the master already had white hair and the young professor sported a dark moustache, meetings presided over by the slender and refined Cosima: a woman who was to become a kind of muse for Nietzsche. Although, as a passionate admirer of Greece, one could imagine the professor travelling to Attica, the circle of the inveterate bachelor didn’t leave Naumburg, Leipzig, Lake Lucerne, Lake Geneva, the Swiss mountains and occasionally the Wagners’ house.

When the philosopher would mature, he would discover to his surprise that even Wagner had only been a way station on his spiritual odyssey.