I use the term ‘schizophrenia’ in its popular sense of a divided mind, not in the psychiatric sense.

A week ago I honoured the retired revolutionary ideologue Michael O’Meara in the context that, unlike him, white nationalists are merely reactionaries.

Today I came up with the idea to look in the discussion threads of the webzine where O’Meara used to post his articles to see when was the last time O’Meara discussed one of his articles with the commenters. I found out it was a reply to a commenter in one of the threads from September 2012:

No offense taken. I was pleased that someone had commented on the Catholic aspect of the piece. Another take on religion is my ‘Only a God Can Save Us’, archived here at C-C.

O’Meara refers to his article on Nietzsche originally published in The Occidental Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 2 (Summer 2008), which Greg Johnson later republished in Counter-Currents on July 1, 2010. This means that O’Meara wrote his article before the Spaniard Evropa Soberana published his long essay on Judea vs. Rome, which I later translated and adopted as the masthead of this site.

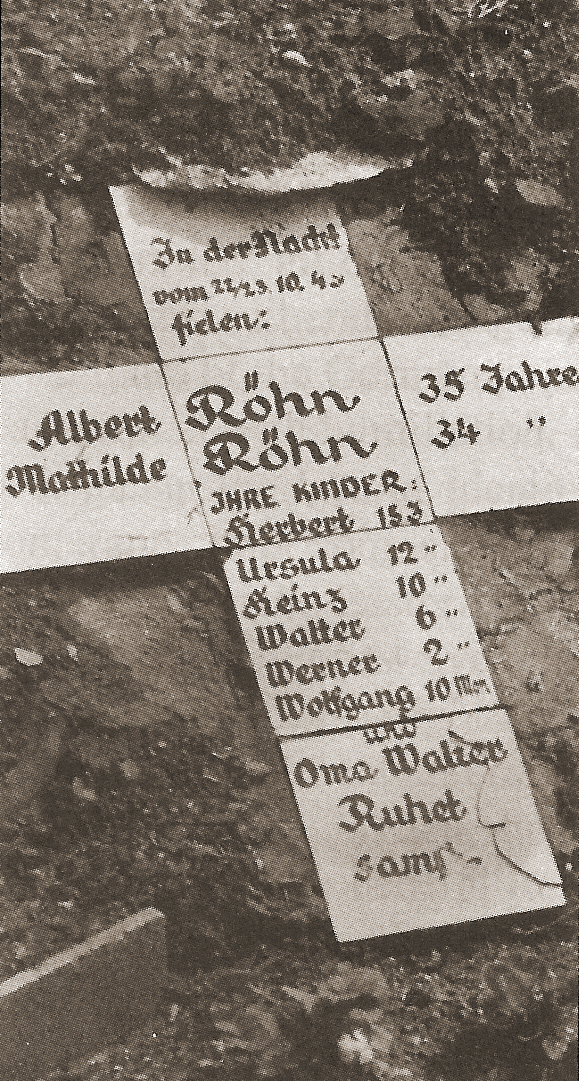

O’Meara’s last comment in Johnson’s webzine reminds me that, in another of his articles, O’Meara said things about Hitler that denoted a critical spirit towards what, in my opinion, has been the apex of western history to date: the Third Reich.

Years ago I asked a question in one of the discussion threads of this site. I didn’t understand why Solzhenitsyn, who so longed for the destruction of the USSR, had not sided with the Nazis who wanted to destroy Bolshevism even after writing his two non-fiction books: The Gulag Archipelago and 200 Years Together. How was this possible, taking into account that Solzhenitsyn was a hawk during the Vietnam War (insofar as he wanted to prevent communism from spreading)? Roger, a British commenter with great sensitivity to why we should reject the degenerate music of the past decades, replied that it was due to Solzhenitsyn’s Christianity.

The Briton hit the nail. It was Solzhenitsyn’s orthodox Christianity that made him ‘schizophrenic’ in the sense of not siding with the good guys during the greatest conflagration between Good and Evil in Western history (check out my most recent sticky post).

The same with Michael O’Meara, whose parents I guess were Irish Catholics. Although O’Meara was far more courageous than today’s white nationalists in suggesting that only revolutionary thinking can save us, he fell short in not appreciating the greatest mental revolution of our day, embodied in the figure of Hitler. And since unlike Roger most American racialists are sympathetic to Christianity, they will remain as schizophrenic as Solzhenitsyn and O’Meara until they stop idealising everything related to the god of the Jews.

Michael’s ‘Only a (((God))) can save us’ is truly schizophrenic if he has in mind the god of his Catholic parents (triple parenthesis added).