In case of mental disorder

‘First do no harm’.

—Hippocratic Oath

Carlos Torre Repetto undressed on a streetcar in 1926 on Fifth Avenue in New York. That happened during the crisis that eventually led him to quit chess. The immigration police deported him in a steamer to Merida. Gabriel Velasco, the author of the only well-written book about the Mexican grandmaster, omits these vital events about his life in his misnamed book The Life and Games of Carlos Torre. I know Velasco personally, but in the next few pages I will break the taboo of not writing about Torre’s life. What did the champions think of the Mexican GM? Alekhine wrote:

(Left, Carlos Torre.) Since 1914 the chess world has not seen a first-rate luminary, one of those players who, like Lasker and Capablanca, mark a milestone in contemporary history… But about six months ago, shortly after the New York Tournament, in the United States appeared a faint light susceptible—at least we hope so—of transforming into a star of the first magnitude. We are talking about the young Carlos Torre, who is nineteen years old and whose short career has peculiarities worthy of attention… Without a doubt, Torre is not mature, which should not be surprising in a young man who has so little serious practice, but we admire the solidity of his game as well as his brilliant tactical qualities that allow him to emerge safely from sometimes dangerous positions in which he finds himself due to lack of experience. After having examined a number of his games, we cannot but congratulate Dr Tarrasch on his resolve to invite him to the next tournament of international masters to be held in Baden-Baden.

Alekhine wrote these words in 1924. Just two years later, when he came within a shot of winning the 1926 Chicago Tournament, Torre had the New York crisis. It is worth saying that the only game that Torre played with Alekhine was a ‘grandmasters draw’ played precisely in the 1925 Baden-Baden tournament. Alekhine, who two years later would dethrone Capablanca, immediately accepted the premature draw proposition by Torre on move fourteen: a sign of the respect he had for the Mexican. That year, the Moscow International Tournament was also held, where Torre made a sensational start. He started out beating three strong masters, including Marshall. He then drew two games with Tartakower and Spielmann to obtain other resounding victories, one of them against Sämisch, with which he placed himself along with Bogoljubov, Rubinstein and Lasker leading the tournament. Lasker said: ‘These first steps by young Torre are undoubtedly the first steps of a future world champion’. One of the most famous games of that tournament was the one Torre played with Lasker himself, who had been world champion from 1894 until Capablanca dethroned him in 1921, four years before the Moscow Tournament. Lasker held the title of champion for twenty-seven years. This great champion had to face Torre in the twelfth round of the tournament and got to obtain a positional advantage in the opening: an opening that was baptised as Torre Attack because the Mexican master introduced it to the practice of masterful chess. But on move 25 something unexpected happened. Word spread in the tournament hall: ‘Torre has sacrificed his queen to Lasker!’, something that rarely happens in professional chess. When it happens it causes a sensation. Within minutes Torre and Lasker had fans around their board. That game, known as ‘The Mill’, carved the name of Torre in chess annals; among others, it deserved an extensive comment from Nimzowitsch in My System.

I have quoted what Alekhine and Lasker thought of Torre’s future. The other champion of the time was Capablanca; as I said, the only Latin American who has won the title of world chess champion. It is an irony that very few Mexicans, and Alfonso Ferriz is an honourable exception, openly say that Torre could have conquered it as well. Capablanca commented on Torre after the Moscow International Tournament: ‘I wouldn’t be surprised if this young man soon started to beat us all’. The only game between Capablanca and Torre was played in that tournament. Capablanca was then the world champion, and his virtuosity lay especially in his mastery and understanding of the end of the game: that is why his game with Torre has a special value. The Mexican played with such precision and ingenuity that he managed to tie a very difficult endgame with the champion. Averbach, the Russian pedagogue, chose this ending to illustrate the theory of positions in his book Comprehensive Chess Endings: Bishop vs. Knight. When analysing the ending one is left with the feeling that this game between Capablanca and Torre is beyond the comprehension of ordinary fans, and that only a chess professor like Averbach and others can decipher it. When he played with Torre, Capablanca was at the height of his abilities. His game with the other Latin American is a tribute to the classic style of both, and should be studied as a paradigm of the endgame of knight against ‘bad’ bishop.

Torre’s arch was like the myth of Phaeton. After Torre’s crisis at the age of twenty-one, which marks the end of his brilliant but fleeting career, he lived without a profession, in a petty way and depending on his family until the early 1950s. He worked for a time in a pharmacy helping his brother in Tamaulipas, but he didn’t make a career or have children. In 1955 Alfonso Ferriz brought him to the capital of Mexico and kept him in a ‘very cheap’ guest house, according to him. Both Ferriz and Alejandro Báez, generous chess lovers in Mexico, tried to help him. Ferriz employed him in a hardware store, but the sixty-four-square aesthete was overwhelmed by the clientele.

During my vacations from junior high to high school, I worked at the Bank of Mexico and over time I purchased chess books for my collection (when I came of age I got rid of all of them). After work at the Bank of Mexico in the centre of the great capital, I would visit El Metropolitano: a chess den that, like all dens, reminds me of the room where opium addicts tried to escape from reality. In that unlikely place I listened to the chess master Alejandro Báez. His talk wasn’t directed at the beardless ephebe I was, but at the fans Carlos Escondrillas, Raúl Ocampo and Benito Ramírez who frequented El Metropolitano. My presence at a distance in those talks in 1973 went unnoticed. But what stuck with me the most was that Báez pointed out Torre’s admiration for San Francisco: the saint who undressed in a public place as a protest against the humiliation that his father had inflicted on him. I deduced from Baez’s talk that imitating the Franciscan buffoonery frustrated Torre’s career.

Carlos Torre died in 1978. The Russian magazine Schachmaty published an account of the tournaments of the time when Torre had flourished, from 1920 to 1926. Although Torre was then fifth in the world behind Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine and Vidmar, he was ahead of masters of the calibre of Nimzowitsch, Rubinstein, Bogoljubov and Reti. Note that this fifth place refers to the early years of Torre’s career. Would he have reached the top without his psychotic breakdown, imitating the man of Assisi? As I said, in the book that Velasco wrote about Torre the premature retirement of the master from Yucatán is taboo.

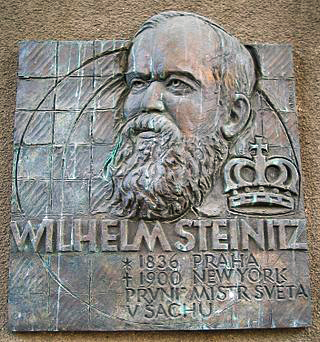

Some Mexican players wonder why if Chigorin, who was close to being a world champion, is considered the father of national chess in Russia, Mexican fans ignore Torre’s figure. One possible answer is that the stigma attached to the term ‘mentally ill’ is the most degrading thing we can imagine: more degrading even than having been in jail or having had a homosexual scandal in Victorian times. It is a subject buried in mystery, and the Criollo Velasco’s reluctance to touch on the subject perpetuates the darkness. Many grandmasters, and even world champions, have suffered nervous breakdowns. Although Steinitz is considered the first world champion, at the dawn of the 20th century he died in abject poverty. It is rumoured that he believed that he was in electrical communication with God, that he could give him a pawn advantage and, in addition, win him.

(Plaque in honour of Wilhelm Steinitz, World Champion from 1886 to 1894, in Prague’s Josefov district.) What causes insanity? Since it is prohibitive for today’s society to ponder the havoc that abusive parents wreak on the mind of the growing child to become an adult, a pseudoscience is tolerated in universities that, without any physical evidence, blames the body of the disturbed individual. This is such an important subject that I have written a dense treatise to unravel it. Here I will limit myself to mentioning some reflections that have to do with chess players.

(Plaque in honour of Wilhelm Steinitz, World Champion from 1886 to 1894, in Prague’s Josefov district.) What causes insanity? Since it is prohibitive for today’s society to ponder the havoc that abusive parents wreak on the mind of the growing child to become an adult, a pseudoscience is tolerated in universities that, without any physical evidence, blames the body of the disturbed individual. This is such an important subject that I have written a dense treatise to unravel it. Here I will limit myself to mentioning some reflections that have to do with chess players.

One of the things that motivated me to write this little book is to settle the score with Carlos Torre’s biography. Unfortunately, there is no relevant biographical material on Torre to know exactly why he lost his sanity. The rumours of his supposed syphilis don’t convince me. Ferriz told me that his friends took him with whores in Moscow. But Torre was sane for the last eighteen years of his life. Had he had neurosyphilis his symptoms would have gone from bad to worse. Torre’s mystical deviations and his imitation of the man from Assisi suggest a psychogenic problem. Likewise, Torre’s nervousness, manifested in the film that captured him playing in Moscow, as well as his habit of smoking four daily packs of Delicados brand cigarettes, suggests a psychogenic problem.

The syphilitic hypothesis that Ferriz told me reminds me of some speculations about Nietzsche’s madness. The author of the Zarathustra suffered from psychosis for almost a dozen years until he died: a psychosis very different from Torre’s fleeting crisis. But as in Torre’s case, blaming a supposed venereal disease for Nietzsche’s disorder has been done so that his tragedy fits within the taboos of our culture.

The root of Nietzsche’s madness was not somatic. The ‘poisonous worms’, as Nietzsche called his mother and his sister in the original version of Ecce Homo (not the version censored by his sister), may have played a role. In The Lost Key Alice Miller suggests that the poisonous pedagogy applied to him by his mother and aunts as a child (his father died prematurely) would drive him mad as an adult. It is worth saying that Stefan Zweig’s splendid literary essay The Struggle Against the Daimon (Hölderlin, Kleist, Nietzsche) has also been translated into English and Spanish. As Nietzsche confesses to us in Ecce Homo, a kind of autobiography where his delusions of grandeur are already noticeable, his mother and sister were ‘the true abysmal thought’ of the philosopher in the face of the eternal return of the identical.

Nor is it convincing what Báez said: that Torre masturbated a lot. In the 19th century the myth that excessive masturbation among boys caused insanity became fashionable; and when old Báez said that Torre was a consummate onanist, I can’t help but remember that myth. Equally wrong is the story of Raúl Ocampo. Although Ocampo is one of the best connoisseurs of Mexican chess, Juan Obregón captured him on the tape recorder maintaining a bizarre theory: that a telegram sent to Torre by the Jews to inform him that his girlfriend was breaking up with him was the trick that triggered the crisis. When I interviewed Alfonso Ferriz, one of the few survivors who knew Torre, he couldn’t tell me anything substantial about the Yucatecan’s childhood and adolescence: the time when his mind was structured and the only thing that could provide us with the lost key to understand his mental state. But one of Ferriz’s anecdotes that most caught my attention was that Torre ‘had an almost mystical respect for women’. He called women las santitas (the holy little ones). ‘How is the little saint?’ was his question when referring to Ferriz’s wife.

I would like to talk a little more about Las Arboledas park. Although Fernando Pérez Melo fled home due to abuse and became destitute, I don’t know of anyone among the park fans who has held his father responsible. Society has been obsessed with not seeing the obvious. As the mother is the most deified figure in Mexico, why not start with her, breaking the taboo of the parental deity? Just as it caused a shock among the ancient Mexicans to see how the bearded people pulled from the pinnacles of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan the effigy of the Coatlicue’s son during the fall of the Aztec capital, for us to mature the figure of the mother has to be defenestrated. When Humboldt visited Mexico, the New Spaniards unearthed the Coatlicue statue to show it to him. They didn’t understand this work of art and they buried it again.

When I speak with Mexicans, I realise that they continue to bury the symbols of those female figures and terrible archetypes that they don’t understand or don’t want to understand. For this reason, the ‘santitas’ that Torre spoke of—compare it with Nietzsche’s expression ‘poisonous worms’—continue to be an object of veneration in Mexico. However, and despite all this speculation of mine, there is no substantial information about Torre’s childhood. Ferriz says that Torre never spoke about his parents or his siblings. So, instead of speculating about his childhood, I will focus on the life of a chess player who died in more recent times and about whom a little more is known.