For an introduction to these series, see here.

Below, some indented excerpts of “Romance and Reality,” the third chapter of Civilisation by Kenneth Clark, after which I offer my comments.

Originally I posted this entry on April 15 of the last year, but now that I posted another entry about Spain’s Teresa of Ávila I would like to see some feedback in the comments section about my thoughts on St. Francis from those interested in child abuse as a subject.

Ellipsis omitted between unquoted passages:

I am in the Gothic world, the world of chivalry, courtesy and romance; a world in which serious things were done with a sense of play—where even war and theology could become a sort of game; and when architecture reached a point of extravagance unequalled in history. After all the great unifying convictions of the twelfth century, High Gothic art can look fantastic and luxurious—what Marxists call conspicuous waste. And yet these centuries produced some of the greatest spirits in the human history of man, amongst them St Francis and Dante.

A couple of pages later, Clark says:

Several of the stories depicted in the [Chartres Cathedral] arches concern Old Testament heroines; and at the corner of the portico is one of the first consciously graceful women in western art. Only a very few years before, women were thought of as the squat, bad-tempered viragos that we see on the front of Winchester Cathedral: these were the women who accompanied the Norsemen to Iceland.

Now look at this embodiment of chastity, lifting her mantle, raising her hand, turning her head with a movement of self-conscious refinement that was to become mannered but here is genuinely modest. She might be Dante’s Beatrice.

Now look at this embodiment of chastity, lifting her mantle, raising her hand, turning her head with a movement of self-conscious refinement that was to become mannered but here is genuinely modest. She might be Dante’s Beatrice.

There, for almost the first time in visual art, one gets a sense of human rapport between man and woman.

About the sentiment of courtly love, on the next page Clark adds that it was entirely unknown to antiquity, and that to the Romans and the Vikings it would have seemed not only absurd but unbelievable.

A ‘love match’ is almost an invention of the late eighteenth century. Medieval marriages were entirely a matter of property, and, as everybody knows, marriage without love means love without marriage.

Then I suppose one must admit that the cult of the Virgin had something to do with it. In this context it sounds rather blasphemous, but the fact remains that one often hardly knows if a medieval love lyric is addresses to the poet’s mistress or to the Virgin Mary.

For all these reasons I think it is permissible to associate the cult of ideal love with the ravishing beauty and delicacy that one finds in the madonnas of the thirteenth century. Were there ever more delicate creatures than the ladies on Gothic ivories? How gross, compared to them, are the great beauties of other woman-worshiping epochs.

When I read these pages for the first time I was surprised to discover that my tastes of women have always been, literally, medieval; especially when I studied closely the face of the woman at the right in the tapestry known as The Lady with the Unicorn, reproduced on a whole page in Clark’s book with more detail than the illustration I’ve just downloaded. I have never fancied the aggressive, Hollywood females whose images are bombarded everywhere through our degenerate media. In fact, what moves me to write are precisely David Lane’s 14 words to preserve the beauty and delicacy of the most spiritual females of the white race.

Alas, it seems that the parents did not treat their delicate daughters well enough during the Middle Ages. Clark said:

So it is all the more surprising to learn that these exquisite creatures got terribly knocked about. It must be true, because there is a manual of how to treat women—actually how to bring up daughters—by a character called the Knight of the Tower of Landry, written in 1370 and so successful that it went on being read as a sort of textbook right up to the sixteenth century—in fact and edition was published with illustrations by Dürer. In it the knight, who is known to have been an exceptionally kind man, describes how disobedient women must be beaten and starved and dragged around by the hair of the head.

And six pages later Clark speaks about the most famous Saint in the High Middle Ages, whose live I would also consider the result of parental abuse:

In the years when the portal of Chartres was being built, a rich young man named Francesco Bernadone suffered a change of heart.

One day when he had fitted himself up in his best clothes in preparation for some chivalrous campaign, he met a poor gentleman whose need seemed to be greater than his own, and gave him his cloak. That night he dreamed that he should rebuild the Celestial City. Later he gave away his possessions so liberally that his father, who was a rich businessman in the Italian town of Assisi, was moved to disown him; whereupon Francesco took off his remaining clothes and said he would possess nothing, absolutely nothing. The Bishop of Assisi hid his nakedness, and afterwards gave him a cloak; and Francesco went off the woods, singing a French song.

The next three years he spent in abject poverty, looking after lepers, who were very much in evidence in the Middle Ages, and rebuilding with his own hands (for he had taken his dream literally) abandoned churches.

He threw away his staff and his sandals and went out bare-foot onto the hills. He said that he had taken poverty for his Lady, partly because he felt that it was discourteous to be in company of anyone poorer than oneself.

From the first everyone recognised that St Francis (as we may now call him) was a religious genius—the greatest, I believe, that Europe has ever produced.

From the first everyone recognised that St Francis (as we may now call him) was a religious genius—the greatest, I believe, that Europe has ever produced.

Francis died in 1226 at the age of forty-three worn out by his austerities. On his deathbed he asked forgiveness of ‘poor brother donkey, my body’ for the hardships he had made it suffer.

Those of Francis’s disciples, called Fraticelli, who clung to his doctrine of poverty were denounced as heretics and burnt at the stake. And for seven hundred years capitalism has continued to grow to its present monstrous proportions. It may seem that St Francis has had no influence at all, because even the humane reformers of the nineteenth century who sometimes invoked him did not wish to exalt or sanctify poverty but to abolish it.

St Francis is a figure of the pure Gothic time—the time of crusades and castles and of the great cathedrals. But already during the lifetime of St Francis another world was growing up, which, for better or worse, is the ancestor of our own, the world of trade and of banking, of cities full of hard-headed men whose aim in life was to grow rich without ceasing to appear respectable.

Of course, Clark could not say that Francesco’s life was a classic case of battered child. Profound studies about child abuse would only start years after the Civilisation series. Today I would say that, since Francesco never wrote a vindictive text—something unthinkable in the Middle Ages that would not appear until Kafka’s letter to his father—, he internalized the parental abuse with such violence that his asceticism took his life prematurely.

What is missing in Clark’s account is that Francesco’s father whipped him in front of all the town people after Francesco stole from his shop several rolls of cloth. After the scourging inflicted by his father, with his own hands, and public humiliation, a citizen of Assisi reminded him that the town statutes allowed the father to incarcerate the rebellious son at home. Pedro shut Francesco in a sweltering, dark warehouse where “Francesco languished without seeing the light except when his father opened the door for Pica [the mother] taking a bowl of soup and a piece of bread.” After several weeks of being locked Francesco escaped and, always fearful of his father, hid in a cave. The earliest texts add that in the cave he often wept with great fear.

Francesco then embarked on a spectacular acting out of his emotional issues with his father. He made a big scene by returning to Assisi, undressing in the town’s square in front of Bishop Guido and addressing the crowd: “Hear all ye, and understand. Until now have I called Pedro Bernadone ‘my father’. But I now give back unto him the money, over which he was vexed, and all the clothes that I have had of him, desiring to say only, ‘Our Father, which art in Heaven,’ instead of ‘My father, Pedro Bernadone.’”

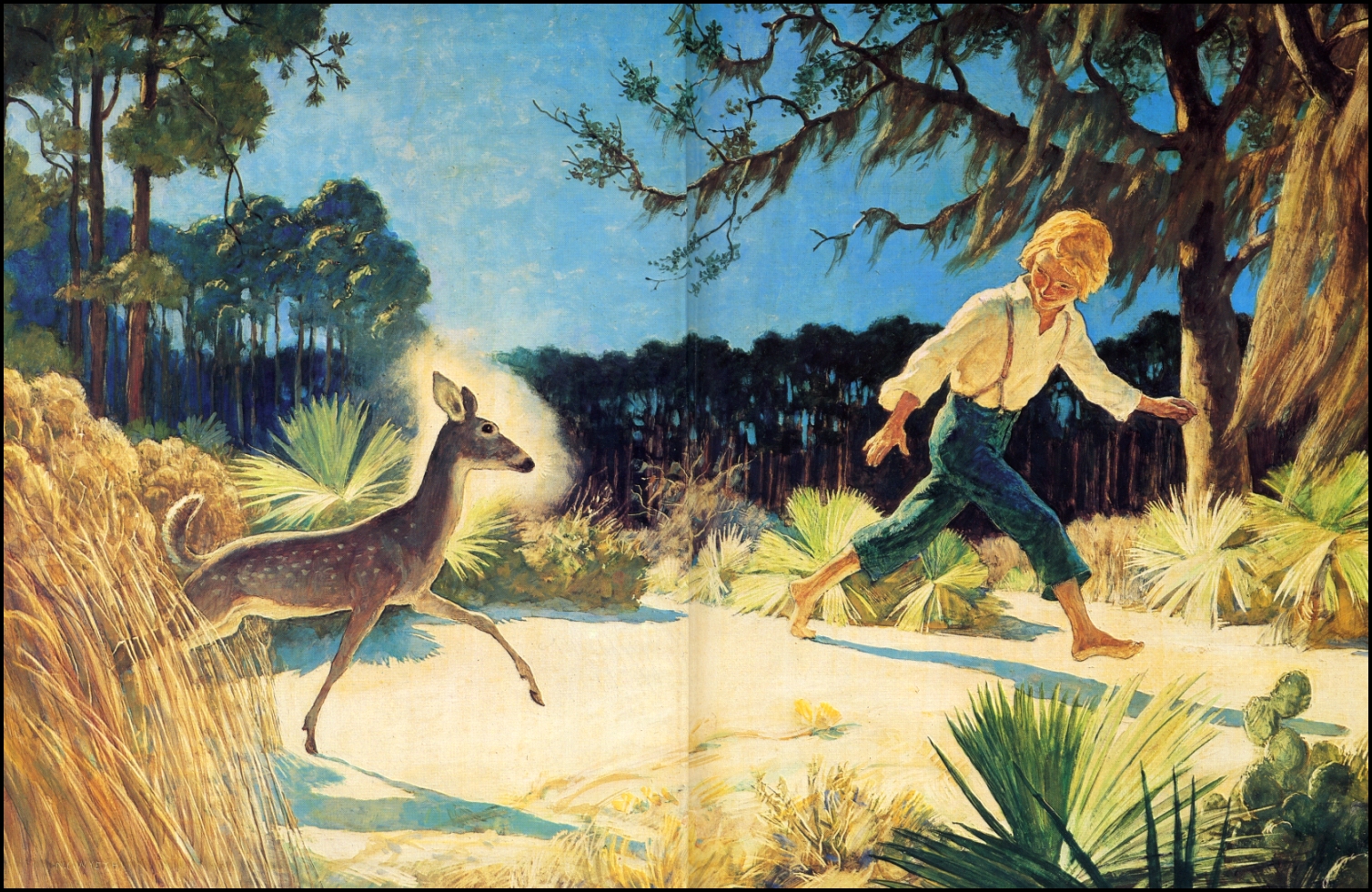

To everyone’s surprise Francesco broke with his wealthy parents forever, thus renouncing any possible reconciliation. So resolute was his parental repudiation, writes a Catholic biographer, that from that day on Pedro and Pica disappear from all the biographies of their son. There is no historical evidence of reconciliation, and no information about his parents or the circumstances of their death. (The pic is taken from Zeffirelli’s adaptation of the life of St Francis.)

To everyone’s surprise Francesco broke with his wealthy parents forever, thus renouncing any possible reconciliation. So resolute was his parental repudiation, writes a Catholic biographer, that from that day on Pedro and Pica disappear from all the biographies of their son. There is no historical evidence of reconciliation, and no information about his parents or the circumstances of their death. (The pic is taken from Zeffirelli’s adaptation of the life of St Francis.)

But I don’t want to diminish the figure of St Francis. Quite the contrary: in my middle teens I wanted to emulate him—and precisely as a result of the abuse inflicted by my father on me. And nowadays our world that has Mammon as its real God—trade, banking and dehumanized cities that are rapidly destroying the white race—, this will always remind me what Clark said about St Francis.

Nevertheless, despite my teenage infatuation with the saintly young man of Assisi, I doubt that poor Francesco’s defence mechanism to protect his mind against his father’s betrayal could be of any help now…

However, it is true that Fernando de Rojas felt alienated in the late 15th century Spain. Some of his biographers even claim that, when Rojas was a bachelor studying in Salamanca, he received the tragic notice that his father, a Jew converted to Catholicism, had been condemned to die at the stake by the Inquisition.

However, it is true that Fernando de Rojas felt alienated in the late 15th century Spain. Some of his biographers even claim that, when Rojas was a bachelor studying in Salamanca, he received the tragic notice that his father, a Jew converted to Catholicism, had been condemned to die at the stake by the Inquisition.