Or:

How the Woke monster originated

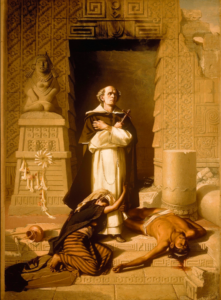

Martin Luther, who as a monk

Martin Luther, who as a monk

had been notably scrawny,

ended up putting on so much

weight that he was denounced

by one adversary as a dainty

for the Devil.

The above image and accompanying text appears in colour in Tom Holland’s book.

Luther had come to believe that true reformatio would be impossible without consigning canons, papal decrees and Aquinas’ philosophy to the flames. Then, in the wake of his meeting with the cardinal, he had come to an even more subversive conclusion… Now, travelling to the diet, Luther was greeted with matching displays of exuberance. Welcoming committees toasted him at the gates of city after city; crowds crammed into churches to hear him preach. As he entered Worms, thousands thronged the streets to catch a glimpse of the man of the hour. [pages 316-317]

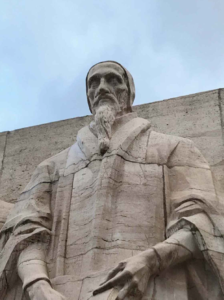

Luther didn’t approve of the historical humiliation that Gregory VII inflicted on Henry IV, which so empowered the papacy. It is worth mentioning here, using Savitri Devi’s philosophy, that unlike us Luther was ‘a man of his time’, as can be seen from the above passage. Discontent with Rome was already in the Germanic air when this obscure monk rebelled.

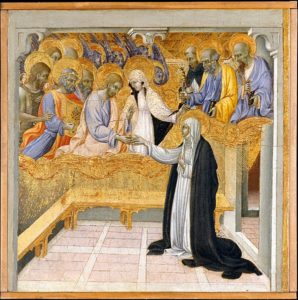

The founding claim of the order promoted by Gregory VII, that the clergy were an order of men radically distinct from the laity, was a swindle and a blasphemy. ‘A Christian man is a perfectly free lord of all, and subject to none.’ So Luther had declared a month before his excommunication, in a pamphlet that he had pointedly sent to the pope. ‘A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all.’ The ceremonies of the Church could not redeem men and women from hell, for it was only God who possessed that power. A priest who laid claim to it by virtue of his celibacy was playing a confidence trick on both his congregation and himself. So lost were mortals to sin that nothing they did, no displays of charity, no mortifications of the flesh, no pilgrimages to gawp at relics, could possibly save them. Only divine love could do that. Salvation was not a reward. Salvation was a gift. [pages 317-318]

Once more: the schizophrenogenic (i.e., it drives you mad) doctrine of salvation from eternal torture thanks to the god of the Jews!

It was in the certitude of this that Luther, the day after his first appearance before Charles V, returned to the bishop’s palace. Asked again if he would renounce his writings, he said that he would not. As dusk thickened, and torches were lit in the crowded hall, Luther fixed his glittering black eyes on his interrogator and boldly scorned all the pretensions of popes and councils. Instead, so he declared, he was bound only by the understanding of scripture that had been revealed to him by the Spirit. ‘My conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience.’

Two days after listening to this bravura display of defiance, Charles V wrote a reply. Obedient to the example of his forebears, he vowed, he would always be a defender of the Catholic faith, ‘the sacred rituals, decrees, ordinances and holy customs’. He therefore had no hesitation in confirming Luther’s excommunication. Nevertheless, he was a man of his word. The promise of safe passage held. Luther was free to depart. He had three weeks to get back to Wittenberg. After that, he would be liable for ‘liquidation’. Luther, leaving Worms, did so as both a hero and an outlaw. The drama of it all, reported in pamphlets that flooded the empire, only compounded his celebrity. Then, halfway back to Wittenberg, another astonishing twist. Travelling in their wagon through Thuringia, Luther and his party were ambushed in a ravine. A posse of horsemen, pointing their crossbows at the travellers, abducted Luther and two of his companions. The fading hoofbeats left behind them nothing but dust. As to who might have taken Luther, and why, there was no clue. Months passed, and still no one seemed any the wiser. It was as though he had simply vanished into thin air.

All the while, though, Luther was in the Wartburg. The castle belonged to Friedrich, whose men had brought him there for safe-keeping. Disguised as a knight, with two servant boys to attend him, but no one to argue with, no one to address, he was miserable. The devil nagged him with temptations. Once, when a strange dog came padding into his room, Luther —who loved dogs dearly—identified it as a demon and threw it out of his tower window. [318-319]

So typical: Christians like to worship crazy and bad people instead of sane and good people. How can the white race not be in bad shape with gurus like Luther (just compare him with Hitler’s priestess)?

He suffered terribly from constipation. ‘Now I sit in pain like a woman in childbirth, ripped up, bloody.’ He did not, as Saint Elizabeth had done when she lived in the castle, welcome suffering. He had come to understand that he could never be saved by good works. It was in the Wartburg that Luther abandoned forever the disciplines of his life as a monk. Instead, he wrote. Lonely in his eyrie, he could look down at the town of Eisenach, where Hilten had prophesied the coming of a great reformer, and believe himself—despite his isolation from the mighty convulsions that he himself had set in train—to be the man foretold…

Now, with his translation, Luther had given Germans everywhere the chance to do the same. All the structures and the traditions of the Roman Church, its hierarchies, and its canons, and its philosophy, had served merely to render scripture an entrapped and feeble thing, much as lime might prevent a bird from taking wing. By liberating it, Luther had set Christians everywhere free to experience it as he had experienced it: as the means to hear God’s living voice. Opening their hearts to the Spirit, they would understand the true meaning of Christianity, just as he had come to understand it. There would be no need for discipline, no need for authority. Antichrist would be routed. All the Christian people at long last would be as one. [319-321]

When I finish this series I will resume the new translation of Hitler’s after-dinner talks. It is very good to have Savitri’s manifesto explaining National Socialism after the catastrophe of 1945. But we need the Führer’s own words to give us an accurate picture of NS.

I have said in the past that the only thing I disagreed with in those talks was Hitler’s position on Charlemagne. But as I recall, he once spoke of Luther without criticising him.

That position differs radically from Nietzsche’s, especially what he wrote in the final pages of The Antichrist. Remember: when an isolated Aryan comes to see through the thick darkness of two millennia, he suffers annihilation in his loneliness because the rest of the white men insist on remaining in darkness. I am closer to that poor alienated man, Nietzsche, when it comes to Luther than to Hitler and his beloved Wagner (the latter, baptised in a Lutheran church).

In short, Nietzsche is right to blame Luther and Germany for the darkness that would flood the post-Renaissance mind. According to the German philosopher, when visiting Rome Luther should have knelt in true grace, with tears in his eyes as he saw how Renaissance painting, sculpture and architecture hinted a coming transvaluation of all values! (something only Wagner, centuries later, would take up again with his pagan operas that we recently reviewed). But Luther did the opposite: he thrust into the Germanic soul not only the New Testament but now the Old Testament: the holy book of the Jews. See William Pierce’s critique of Luther in Who We Are, already quoted in a couple of ‘Our books’.