Or:

“No Jews, no Arabs, no communists

have done so much damage

to the White gene pool

as Whites themselves”

The above is a quotation from Tom Sunic’s 2010 essay, “Race and Religion: Awkward Friends of the White Man” published in three parts at The Occidental Observer (here, here and here) where he also analyzes the Jewish Question from a viewpoint so alien for TOO readers that zero comments appeared in those three instalments (perhaps the admins closed the comments to prevent flaming discussions).

Below I reproduce the whole article in a single entry because it throws some light on an ongoing discussion at Counter-Currents with me about whether or not common sense dictates that the Jews “are our deadliest single enemy.”

There is a widespread idea among White nationalists worldwide that Whites need to resurrect their Christian heritage in order to be better able to retrieve their racial, religious and cultural identity. Another proposal common among White nationalists is that the liberal system needs to put an end to non-White, non-Christian immigration, which would then pave the way for polishing up the vanishing White gene pool. Another far-flung idea is that the influence of Jews must be curtailed if not stopped altogether, so that all social ills can be cured. Last but not least, the liberal system needs to be replaced by a nationalist, nativist, populist, “right wing”, White government.

There is a widespread idea among White nationalists worldwide that Whites need to resurrect their Christian heritage in order to be better able to retrieve their racial, religious and cultural identity. Another proposal common among White nationalists is that the liberal system needs to put an end to non-White, non-Christian immigration, which would then pave the way for polishing up the vanishing White gene pool. Another far-flung idea is that the influence of Jews must be curtailed if not stopped altogether, so that all social ills can be cured. Last but not least, the liberal system needs to be replaced by a nationalist, nativist, populist, “right wing”, White government.

However credible these proposals sound, they are naive in their formulations, superficial in scope, and dangerous in their possible implementation. They deal with the political consequences of the problem rather than probing into its philosophical and historical causes. Even if miraculously all non-White, non-Christian residents were to disappear from America and the European Union and even if all liberal policies were to be abandoned, it is unlikely that the White man would solve deep-rooted problems of his own racial and religious identity.

Science and quackery

Before even attempting to offer some salutary suggestions, one must be aware of the oppressive weight of the dominant ideas and their “scientific”—a.k.a. “politically correct”—ambience in the modern liberal system. Our postmodern epoch is profoundly saturated by egalitarian and economistic dogmas. Regardless how much empirical artillery one can muster in defence of the uniqueness of the White gene pool, and regardless of how many facts one can enumerate that point to diverse intellectual achievements of different races, no such evidence will elicit social or academic approval. In fact, if loudly uttered, the evidence may be considered a felony in some Western countries. In our so-called free and secular society, new religions, such as the religion of racial promiscuity and the theology of the free market have replaced the old Christian belief system. Only when these new secular dogmas or political theologies start crumbling down—which may soon be the case—alternative views about race and the meaning of the sacred may appear.

The historical irony is that it was not the Other, i.e. the non-White, who invented the arsenal of bashing the White man. It was the White man himself—both with his Christian atonement and now with his liberal expiation of the feelings of guilt. Therefore, any arguments offered in defence of racial separation will inevitably be perceived by the Other, i.e. by a non-White (and his guilt-ridden White masters) as racist. Not wanting to contravene the moral imperatives that they invented, Western man must once again posture as an example of global justice that needs to be copied by all races—albeit this time around as a negative role model.

Alain de Benoist writes that liberalism has been a racist system par excellence. In the late 19th century, it preached exclusive racism. Now, in the 21st century it preaches inclusive racism. By herding non European races from all over the world into a rootless a-racial and a-historical agnostic consumer society and by preaching ecumenical miscegenation, the West nonetheless holds its undisputed role of a truth maker—of course, this time around under the auspices of the self-hating, self-flagellating White male.

It must be stated that it was not the Colored, but the White man who had crafted the ideology of self-denial and the concomitant ideology of universal human rights, as well as the ideas of interracial promiscuity. Therefore, any modest scholarly argument suggesting proofs of racial inequality is untenable today. How can one persuasively argue about the existence of different races if the modern system lexically, conceptually, scientifically, ideologically, theologically, and last, but not least, judicially, forbids the slightest idea of race segregation—except when it evokes skin-deep exotic escapades into musical and culinary prowess of non-European races?

Most American White nationalists use Thomas Jefferson as their patron saint, frequently associating his name with “good old times” of the American Declaration of Independence. Those were the times when the White man was indeed in command of his destiny. The White founding fathers stated: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Yet the abstract words “all men” combined with the invocation of a deistic and distant “creator” had a specific significance in the mind of Enlightenment-groomed Jefferson. Two hundred years later, however, his words ring a different bell in the ears of a real Muslim Somali or a Catholic Cholo planning to move to the United States.

Who can, therefore deny to masses of non-European non-Christian immigrants from all parts of the world to freely extrapolate, for their own racial benefit, Jefferson’s words that “all men are created equal”? The self-perception of Jefferson and his Enlightenment-influenced compatriots of 18th-century Europe and America were light miles away from the perception of his words by today’s non-Whites in search of “the American dream.” Wailing and whining that “Jefferson did not mean this; he meant that”—is a waste of time. Similar to many historical documents claiming “scientific “ or “self-evident” nature, be they of the religious, historical or judicial provenance, the American Declaration bears witness to the classical cleavage between the former signifier and the modern signified which has become the subject of its own semantic sliding—with ominous consequences for Whites worldwide.

A witty Southern antebellum lawyer, a racialist writer, with a good sense of the language, John Fitzhugh, calls Jefferson’s words “abstractions”.

The verbal tricks such as “we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal”, are bottomless pits out of which torrents of modern new demands keep arising: It is, we believe, conceded on all hands, that men are not born physically, morally or intellectually equal—some are males, some females, some from birth large, strong, and healthy, others weak, small and sickly—some are naturally amiable, others prone to all kinds of wickedness—some brave others timid. (George Fitzhugh, Sociology for the South, or the Failure of Free Society 1854, pp. 177-178).

Contemporary geneticists and biologists are no less vulnerable than philosophers and sociologists to dominant political theologies. What was considered scientific during the first part of the 20th century in Europe and the United States by many prominent scholars writing about race is viewed today as preposterous and criminal. The dominant dogma idea of egalitarianism must give its final blessing in explaining or explaining away any scientific discovery.

This is particularly true regarding the endless debate about “nature vs. nurture” (heredity vs. environment). If one accepts the dominant idea that the factor of environment (“nurture”) is crucial in shaping the destiny of different races—then it is useless to talk about differences among races. If all individuals, all races, are equal, they are expandable and replaceable at will!

The dogma of the inheritance of acquired characteristics is a matter of life or death for Marxism. This was recognized with precision by the Soviet rulers… As [Fritz] Lenz, one of the most important eugenicists [“racial hygienists”] pointed out, the Soviet rulers must for one obvious reason cling on to the doctrine of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. They need this doctrine for calming their conscience. If everything really depends on the environment, this means that the slaughtering carried out by Bolshevism of so many carriers of valuable hereditary endowment, is not an irreparable loss, but rather a state-regulated change of the environment. (Gustav Franke, Vererbung und Rasse [Heredity and Race], 1938, 1943, pp. 113-114, my trans.)

Needless to say, Franke, Lenz and thousands of German and other European anthropologists, geneticians and biologists disappeared from the reading list, after being denounced either as “bad Nazis” or “atheists”. Although the field of the former Soviet social sciences is considered today as quackery, its egalitarian, Marxist residue of omnipotent inheritance of acquired characteristics is religiously pursued by the post-Christian, neoliberal capitalist West. In layman’s terms, this means that the floodgates for mass immigration of non-Europeans must be kept wide open. Racial promiscuity and miscegenation must be enforced. It is science! It is the law!

Racial promiscuity in the age of high IQ morons

“Dorks”, “idiots”, “morons”, “halfwits”, “dimwits”, are words used daily in the portrayal of our pesky interlocutors. But what if some of our intelligent interlocutors are indeed stupid? It is a historical truism that most world explorers, famous statesmen, most scientists, most Nobel prize winners, have been White people with predominantly Nordic stature and dolichocephalic skull. It is a truism that most prisoners in America and Europe are crossbreeds of non-European out-groups, with the remnants of Whites, whose criminal record can be traced to inborn genetic disorders in their family tree. A long time ago William Sadler, a forgotten eugenicist from the Chicago Medical School, wrote a book about “the aristocracy of the unfit” that cannot be improved by any amount of do-good sermonizing: “Mental defectiveness (moronism) is hereditary and constitutional, and consequently not amenable to our preachings, asylums, hospitals, reformatories, penitentiaries, etc. We must ever bear in mind that each year a new quota of defectives is born with statistical regularity.” (Race Decadence, 1922, p. 254).

The modern media-induced dumbing down process, combined with inborn mental deficiencies of an ever growing number of White people is being accelerated by massive inflow of low IQ immigrants, already conditioned to capitalize on post-Christian and liberal guilt feelings of the White man. As in the ex-Soviet Union, the dominant theology of egalitarianism and TV shows incessantly role-modeling interracial sex only accelerate the culture of mediocrity and the culture of death.

People get arrested for financial fraud or homicide. Yet professors in humanities in America and Europe, when propagating Lamarckian science-fiction and egalitarian pipe dreams get promoted. A physiologist and a Nobel Prize winner, the late French racialist Charles Richet, in his book “The Stupid Man” (L’homme stupide, 1919), understood that high IQ is not a trademark of intellectual disinterestedness or a sign of value-free judgments. Stupid, abnormal decisions are often made by high IQ people, who are driven by utopian belief systems.

High IQ among Whites, if not accompanied of good character, psychological introspection, nobility of spirit and a sense of honor—is worthless. The architects of the largest serial genocides in the history of mankind, writes Rudolf Kommos (Juden hinter Stalin, 1938, 1944), were intelligent Bolsheviks, mostly of Jewish origin, whose inborn millenarian, eschatological and chiliastic mindset, had led them to believe that dozens of millions of Russian civilians needed be wiped out.

Stupidity does not mean that a person has not understood something; rather it means that he behaves as if he did not understand anything. When a person moves headlong toward disaster in order to satisfy his prejudices, his errors, his defective and false reasoning—this is inexcusable. It is far better to be deprived of intelligence than to make poor use of it… Judging by our acts we become more stupid as we become less ignorant. (Charles Richet, L’homme stupide, 1919, p 15, my trans.)

European and American history has been full of highly intelligent individuals endorsing abnormal religious and political beliefs. This is particularly true for many temporary White European and American left-leaning academics who, although showing high IQ, are narrow-minded, spineless individuals of no integrity, or race traitors of dubious character. Low IQ Cholos or affirmative action Blacks are just happy pawns in their conspiratorial and suicidal game. The father of European racialism and a man whose work left an important impact on the study of race in the early 20th century, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, summarized how cultivated men, when driven by theological or ideological passions, commit deadly mistakes:

It is virtually impossible to change by means of education the intellectual type of an individual, however intelligent he may be. Any education will be impotent to provide him with audacity and initiative. It is heredity that decides on his gifts. I was often surprised by the intensity of gregarious spirit amidst the most instructed men… Each minor manifestation of an independent idea hurts them; they reject a priori everything as pernicious errors that has not been taught to them by their masters. (Georges Vacher de Lapouge, Les sélections sociales, 1896, p.104; my trans.)

Is this not a proof that the worst enemy of the White man can often be his fellow White man?

♣

A non-White immigrant residing in Europe or America must be bewildered, bedeviled and bemused by the spectacle offered by his White hosts. On the one hand he must be scared to death of those unpredictable, self-assured, conceited White males and their attractive White women who are capable of walking on the moon and curing plague in his jungle or his desert. On the other, he gleefully rejoices when he hears stories of endless religious and ideological conflicts amidst his White hosts. The pristine, pastoral and puerile picture of the White race, so dearly longed for by modern White nationalists, is daily belied by permanent religious bickering, jealousy and character smearing within the White rank and file. Add to that murderous intra-White wars that have rocked Europe and America for centuries, one wonders whether the proverbial and much vaunted Aryan, Promethean, and Faustian man, is worthy of a better future.

For the greater glory of God

Surely, the White man saved Greco-Roman Europe from the Levantine Hannibal’s incursion, which nearly resulted in a catastrophe in 216 b.c. at Cannae, in southern Italy. The White man also stopped Attila’s Hunic hordes on the Catalaunian Fields in France in 451 a.d. The grandfather of Charlemagne, Charles Martel, defeated Arab predators near Tours, in France in 732. One thousand years later in 1717, a short and slim Italo-French Catholic hero, Prince Eugene of Savoy, finally removed the Islamic threat from the Balkans.

But the unparalleled White will to power, couched later on in Christian millenarianism, had also prompted large crusades against “infidels.” Their commander in chief, the pious Godfrey de Bouillon, did not have pangs of consciousness after his knights had put to the sword thousands of Muslim civilians in captured Jerusalem in 1099 a.d. All was well meant for the greater glory of Yahweh!

The power of the newly discovered universal religion and the expectancy of the “end of history,” later to be followed by bizarre beliefs in “global democracy,” often eclipsed racial awareness among Whites. As a rule, when White princes ran out of Muslim or Jewish infidels—they began whacking each other in the name of their Semitic deities or latter day democracies. The 6’4” tall Charlemagne, in the name of his anticipated Christian bliss, went on the killing spree against his fellow pagan Germans. In 782 a.d. he decapitated several thousand of the finest crop of Nordic Saxons, thereby earning himself a saintly name of the “butcher of the Saxons” (Sachsenschlächter).

And on and on the story goes with true Christian or true democracy believers. No Jews, no Arabs, no communists have done so much damage to the White gene pool as Whites themselves. The Thirty Years War (1617–1647) fought amidst European Christians with utmost savagery, wiped out two thirds of the finest German racial stock, over 6 million people. The crazed papist Croatian mercenaries, under Wallenstein’s command, considered it a Royal and Catholic duty to kill off Lutherans, a dark period so well described by the great German poet and dramatist Friedrich Schiller. Even today in Europe the words “Croat years” (Kroatenjahre) are associated with the years of hunger and pestilence.

Nor did Oliver Cromwell’s troops—his Ironsides—during the English civil war, fare much better. Surely, as brave Puritans they did not drink, they did not whore, they did not gamble—they only specialized in skinning Irish Catholic peasants alive. Not only did their chief, the Nordic looking fanatic Cromwell consider himself more Jewish than the Jews—he actually brought them back from continental Europe, with far-reaching consequence both for England and America.

A slim, intelligent, Nordic looking, yet emotionally unstable manic depressive, William Sherman, burnt down Atlanta in 1864—probably in the hopes of fostering a better brand of democracy for the South. We may also probe some day into the paleocortex of the Nordic skull of an airborne Midwest Christian ex-choir boy, who joyfully dropped firebombs on German civilians during WWII. The results may not be too difficult to detect considering that the same Biblical mindset was re-enacted in 2002 in Iraq by G. W. Bush and his advisors enraptured by Talmudic tales of “weapons of mass destruction.” Biblical or liberal-democratic crimes, when couched in political choseness and theological messianism are perfect tools for a perfectly good consciousness.

Many European White nationalists are dazed at good looking Nordic men and women from the Bible Belt raving, ranting and dancing on TV in trance to Christian-Zionist tunes. Equally stunned are American White nationalists when they observe blood-stained victimhood quarrels pitting Irish against English nationalists, Serb against Croat nationalists, Ukrainian against Russian nationalists, Walloon against Flemish nationalists, Polish against German nationalists, and so on and on.

The faith or the sacred?

No subject is so dangerous to address among White nationalists as the Christian religion. It is commendable to lambast Muslims, who are on the respectable hit-parade of the Axis of Evil. Jews also come in handy in a wholesale package of evil, which needs to be expiated—at least occasionally. But any critical examination of Judeo-Christian intolerance is viewed with suspicion and usually attributed to distinct groups of White people, such as agnostics or modern day self-proclaimed pagans.

Why did the White man accept the Semitic spiritual baggage of Christianity even though it did not quite fit with his racial-spiritual endowments? The unavoidable racialist thinker Hans Günther—a man of staggering erudition and knowledgeable not only of the laws of heredity, but also of comparative religions—reminds us that the submissive and slavish relation of man to God is especially characteristic of Semitic peoples. In his important little book, The Religious Attitudes of the Indo-Europeans, he teaches us about the main aspects of racial psychology of old Europeans. We also learn that Yahweh is a merciless totalitarian god who must be revered—and feared.

Ancient Europeans did not believe in any kind of salvation. They believed in inexorable destiny. Gods were their friends and enemies, as seen in ancient Greece and Rome. Among old Europeans the notion of polarity between Heaven and Earth, between soul and body, i.e., dualism of any kind, was nonexistent. Man was part of an organic whole, embedded in his tribe and race, and tolerant of others’ religious ideas:

Mutual tolerance of religious forms is a distinctive feature of the Indo-European. The memorial stones in the Roman-Teutonic frontier region reveal through their inscriptions that the Roman frontier troops and settlers not only honoured their own Gods, but also respected the local deity of the Teutons, the genius huius loci. (p. 36)

The messianic, chiliastic, or “communistic” mindset was unknown among ancient Europeans. They could not care less which gods other races, other tribes or other peoples believed in. Wars that they fought against the adversary were bloody, but they did not have the goal of converting the adversary and imposing on him the beliefs contrary to his racial heritage. Homer’s epic The Iliad is the best example. The self-serving, yet truly racist liberal-communistic endeavour, to wage “final and just war” in order to “make the world safe for democracy,” was something inconceivable for ancient Europeans.

Zeal to convert and intolerance have always remained alien to every aspect of Indo-European religiosity. In this is revealed the Nordic sense of distance between one man and another, modesty which proscribes intrusion upon the spiritual domains of other men. One cannot imagine a true Hellene preaching his religious ideas to a non-Hellene. (p.36)

A German-British racialist author of the early 20th century, Houston Stewart Chamberlain in his The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century writes that “a final judgment shows the intellectual renaissance to be the work of Race in opposition to the universal Church which knows no Race (p. 326). Unlike Christianity, which preaches individual salvation, for ancient Europeans life can only have a meaning within the in-group—their tribe, their polis, or their civitas. Outside those social structures, life means nothing.

In the 1st century, words of far-reaching consequence for all Whites were pronounced by a Jewish heretic, the Apostle St. Paul, to the people of Galatia, an area in Asia Minor once populated by the Gauls (i.e., Celts). Galatia was then well underway to become a case study of multicultural debauchery—similar to today’s Los Angeles: “You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.” (Galatians 3:28).

Christianity became thus a Universalist religion with a special mission to transform the Other into the Same. The seeds of egalitarianism—albeit on the religious, not yet on the secular level—were sown. The pagan notion of the mystical sacred was gradually being displaced by the dogmatic notion of one omnipotent faith:

Yahweh in the Bible is not just the only and unique god who wields power. He is only and unique in the sense of his Absolute Otherness. He is only and unique in his own kind—that is to say he is the Absolute Other away from this world. The essence of biblical monotheism is its constitutive dualism… Where paganism establishes bridges and links, the monotheism of the Bible creates fractures, ruptures, and forbids anybody to span them. Yahweh forbids mixtures between Heaven and Earth, between Man and the Divine, between humans and other living beings, between Israel and the “nations.” (Alain de Benoist, “Sacré païen et désacralisation judéo-chrétienne” in Quelle religion pour l’Europe? [Which Religion for Europe?] 1990, pp 30-31, my trans.)

Although Christian Churches never publicly endorsed racial miscegenation, they did not endorse racial segregation either. This was true for the Catholic Church and its flock, as observed by the early French sociologist and racialist Gustave Le Bon. Consequently, Catholic Spaniards of White racial stock in Latin America could not halt decadence and debauchery in their new homelands as WASPs in North America did—at least prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Naturally, it is not only in politics that decadence of the Latin race, which inhabits the south of America, manifests itself. It is in all elements of its civilization. If they were reduced to themselves, these unhappy republics would return to barbarism. All industry, all commerce is in the hands of foreigners, English, Americans and Germans. Valparaiso has become an English town. Nothing would remain of Chile if its foreigners were removed (p. 86). (Gustave Le Bon, Lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples, 1895, my trans.).

Later, in 1938, in light of eugenic and racial laws adopted not only in Germany and Italy, but also in other European countries and many states in America, Pope Pius XI made his famous statement: “It is forgotten that mankind is one large and overwhelming Catholic race.” This statement was to become part of his planned encyclical under the name The unity of the human race.

“The unity of the human race”, as noble as these words may sound, is a highly abstract concept. On a secular level communist and liberal intellectuals constantly toy with it—in order to suppress real tribes, real nations, real peoples and their real racial uniqueness. Even if this white race, constantly defamed as “wicked”, “racist” , “bigoted” and “fascist,” disappeared from the face of the earth, non-White immigrants know that they would soon have to climb back onto their native tree or return to their despotic cave.

♣

Each religion is exclusive and exclusionary, which inevitably results in downplaying or, even worse, in denial of other religions. By definition, all Christian denominations, in order to strengthen their theological credibility, have historically resorted to this type of “negative legitimacy.” Yet, despite devastating wars among Whites of different Christian persuasions, Christianity, as a whole, has retained its transcendental value, which has made life more or less liveable.

No longer is this the case with postmodern “civil religions” that ignore the sacred. Their nature of exclusion is already resulting in intellectual terror—that may soon be followed by real state-sponsored physical terror.

Civil religions also have their holy shrines, their holy relics, their pontiffs, their canons, their promises and their menaces. Failure to believe in them—or failure to at least pretend to believe in them—results, as a legal scholar of Catholic persuasion, Carl Schmitt wrote, in a heretic’s removal from the category of human beings. Among new civil religions one could enumerate the religion of multiculturalism, the religion of antifascism, the religion of the Holocaust, and the religion of economic progress.

Many Whites make a fundamental mistake when they portray new civil religions as part of an organized conspiracy of a small number of wicked people. In essence, civil religions are just secular transpositions of the Judeo-Christian monotheist mindset which, when combined with an inborn sense of tolerance and congenial naïveté of the White people, makes them susceptible to their enchanting effects.

The folly of the compound noun: “anti-Semitism”

As a result of semantic sliding of political concepts, the Jewish-born thinker and the father of the secular religion of communism, Karl Marx, would likely be charged today with “anti-Semitism” or the “incitement to racial hatred.” Leftist scholars usually do not wish to subject his little booklet, On the Jewish Question (1844) to critical analysis. Consider the following:

The Jew has emancipated himself in a Jewish manner, not only because he has acquired financial power, but also because, through him and also apart from him, money has become a world power and the practical Jewish spirit has become the practical spirit of the Christian nations. The Jews have emancipated themselves insofar as the Christians have become Jews.

Of particular significance is Marx’ last sentence “insofar as the Christians have become Jews.” In fact the White man has “jewified” himself by embracing the fundaments of the Jewish belief system, which, paradoxically, he uses now in criticizing Jews. Christian anti-Semitism can be described, therefore, as a peculiar form of neurosis. Christian anti-Semites resent the Jews while mimicking the framework of resentment borrowed from Jews. Accordingly, even the Jewish god Yahweh was destined to become the anti-Semitic God of White Christians! In the name of this God, persecutions against Jews were conducted by White non-Jews. Simply put, the White non-Jew has been denying for centuries to the Jew his self-appointed “otherness” i.e. his uniqueness and his self-chosenness, while desperately striving to re-appropriate that same Jewish otherness and that same uniqueness, be it in the acceptance of Biblical tales, be it the espousal of the concept of linear time, be it in the belief of the end of history.

To face up to the purported bad sides of Judaism by using Christian tools, is futile. This is the argument of the German philosopher Eugen Dühring, who notes that “Christianity is an offshoot of Judaism” and “a Christian, when he rightfully comprehends himself as such, cannot be a serious and complete anti-Semite.” (Die Judenfrage als Frage des Rassencharakters, 1901). Dühring was a prominent German socialist philosopher, contemporary, but also a foe of Marx. Like most German socialist thinkers of the late 19th century he was an anti-Semite, in so far as he saw in the Jewry the incarnation of capitalism. Dühring notes that “historical Christianity, when observed in its true spirit, and all things considered, has been a backlash within and against Judaism, but it has also emerged from it and to some extent in its fashion.” (p. 25-26).

Gradually, the so-called intellectual anti-Semitism, based on economic and sociological factors, was replaced by racial anti-Semitism. As was to be expected, thousands of German scholars who had delved into the critical description of the racial traits of Jews disappeared after WWII from the radar screen, and their books went up in flames. As a rule, when they are quoted today in American or European academia by half-knowledgeable, tenure-scared professors, they are pathologized as “monsters” or proverbial “Nazis”, or their words are taken out of context.

A German legal scholar and a local government leader of the NSDAP of the city of Magdeburg, Professor Helmut Nicolai, writes that

Germanic loyalty (‘Treue’) is contrary to the Oriental concept of obedience (‘Gehorsam’). A loyal person operates within the spirit of a person to whom he shows loyalty. Loyalty always presupposes inner mutual understanding. By contrast, obedience refers to the achievement of an order, to the implementation of a letter of the word… Laws cannot create a better legal framework for the rule of law; rather it is a better people who can achieve that. (Die Rassengesetzliche Rechtslehre) (“Racial Provisions of Law in Jurisprudence,” 1933. p. 44)

Naturally, the question that comes to mind today is the meaning of natural law with the dogma that all people are equal. Is it possible to have the same constitutional rights for different peoples of different gene pools and different cultures? A Palestinian fellah views his rights differently from a New York-born Jewish kibbutznik on the West bank; an Aborigine from New Zealand has a different concept of justice than a White farmer; a Christian Orthodox Serb has a different concept of historical justice from his neighbour, a Muslim Albanian.

Anti-anti-Semitism

As a response to the world-wide communist and liberal attacks against the passage of the Nuremberg racial laws in 1935 in National Socialist Germany, Professor Walter Gross, Head of the Bureau of Racial Politics of the NSDAP, wrote:

The opinion has been kicked around the globe that Germany had invented sterilisation and that it has afterward medically and scientifically dressed it up exclusively in an effort to get rid of its opponents. This is complete insanity! If we really had an intention to make a political opponent harmless we would certainly not sterilize him as he would continue to live as happily ever after for the next 60 years at our expenses”… “The fact that we consider communism a hereditary disease that needs to be combated, the fact that procreation of the progeny must be prevented—while allowing communists to roam around freely—this is really a suggestion that in no way does justice to the opinion of the German people and its state. (Walter Gross, Der deutsche Rassengedanke und die Welt, 1939, p. 17–18)

Gross pleads for racial harmony of diverse nations and describes favourably racial and cultural endowments of the Japanese, while rejecting the accusation of German racial superiority over other races. He notes, however, that “no agreement is possible with theoretical systems of the international kind… because they are based on incredible lie, i.e. the lie of the equality of all people” (p. 30).

Another highly placed legal scholar in National Socialist Germany, professor at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, Falk Ruttke, writes that

we will never solve the Jewish question through fanatical “anti-Semitism,” as the history of Judaism, not only in Germany, but the history from all over the world teaches us. The solution of the Jewish question is only possible through racial awareness (“Rassengedanke”) that is fair to each race. We shall never implement that unless we distinguish between nation and race. “National Socialism is not anti-Semitic, it is a-Semitic” (Falk Ruttke, Rasse, Recht und Volk, from Jugend und Recht, p. 30, 1937, italics in the original).

In his famous book about racial psychology of Jews, teeming with quotes by Orientalists, linguists, psychiatrists and other scholars, Hans Günther writes how Christianity, in adopting the Jewish god Yahweh, has ended up endorsing the concept of the “chosen people,” thereby greatly helping with the jewification (“Verjudung”) of the Western society. (p. 313)

Christian doctrines, historically speaking, paralyze the spirit of the West in its conventional and lasting dispute with the spirit of the Orient and in particularly with that of Judaism. Through its control of the press and intelligence service it is not at all difficult today for Jewry to give the Zeitgeist [spirit of the time] each time the direction that is most appropriate for Jews, while diverting the spiritual life of non-Jewish peoples away from their inborn spiritual values, always leading them to those spiritual values that appear as the most authoritative to Judaism. (p. 314)

In his numerous books the geneticist and biologist Fritz Lenz, who was held in high esteem by the scientific establishment in National Socialist Germany, examines the genetically conditioned proclivities among Jews, such as their extraordinary skill for moralistic pathos, the sense for empathy, mimicry, and the capability of provoking sentimental outbursts about painful injustice (“Schmerzenszug”) among deprived masses.

In revolutionary movements hysteric prone Jews play a big role because they can project themselves in utopian imaginations and therefore they can make convincing promises with far-reaching inner veracity… Not only Marx and Lasalle were Jews, but also in the recent times Eisner, Rosa Luxembourg. Leviné, Toller, Landauer, Trotsky and among others… Kahn, who praises the Jewish revolutionaries as the saviors of mankind and sees in them “a specific Jewish manner of the world-view and historical activity.” Lenz, Menschliche Erblehre (A Lesson about Human Heredity), 1936, p. 752–753

What German geneticists and anthropologists, such as Fritz Lenz, Hans Günther, Erwin Baur, Eugen Fischer and thousands of other scholars wrote about Jews had already been written and discussed—albeit from a philosophical, artistic and literary point of view—by thousands of European writers, poets and artists. From the ancient Roman thinker Tacitus to the English writer William Shakespeare, from the ancient Roman thinker Seneca, to the French novelist and satirist, L. Ferdinand Céline, one encounters in the prose of countless European authors occasional and not so occasional critical remarks about the Jewish character—remarks that could easily be called today anti-Semitic. Should these “anti-Semitic” authors, novelists, or poets be called insane? If so, then the entire European cultural heritage must be banned and labeled insane.

Excluding the Jew, while using his theological and ideological concepts is a form of latent phobia among Whites, of which Jews are very well aware of. Criticizing a strong Jewish influence in Western societies on the one hand, while embracing Jewish religious and secular prophets on the other, will lead to further tensions and only enhance the Jewish sense of self-chosenness and their timeless victimhood. In turn, this will only give rise to more anti-Jewish hatred with tragic consequences for all. The prime culprits are not Jews or Whites, but rather a civil religion of egalitarianism with its postmodern offshoots of universalism and multiculturalism.

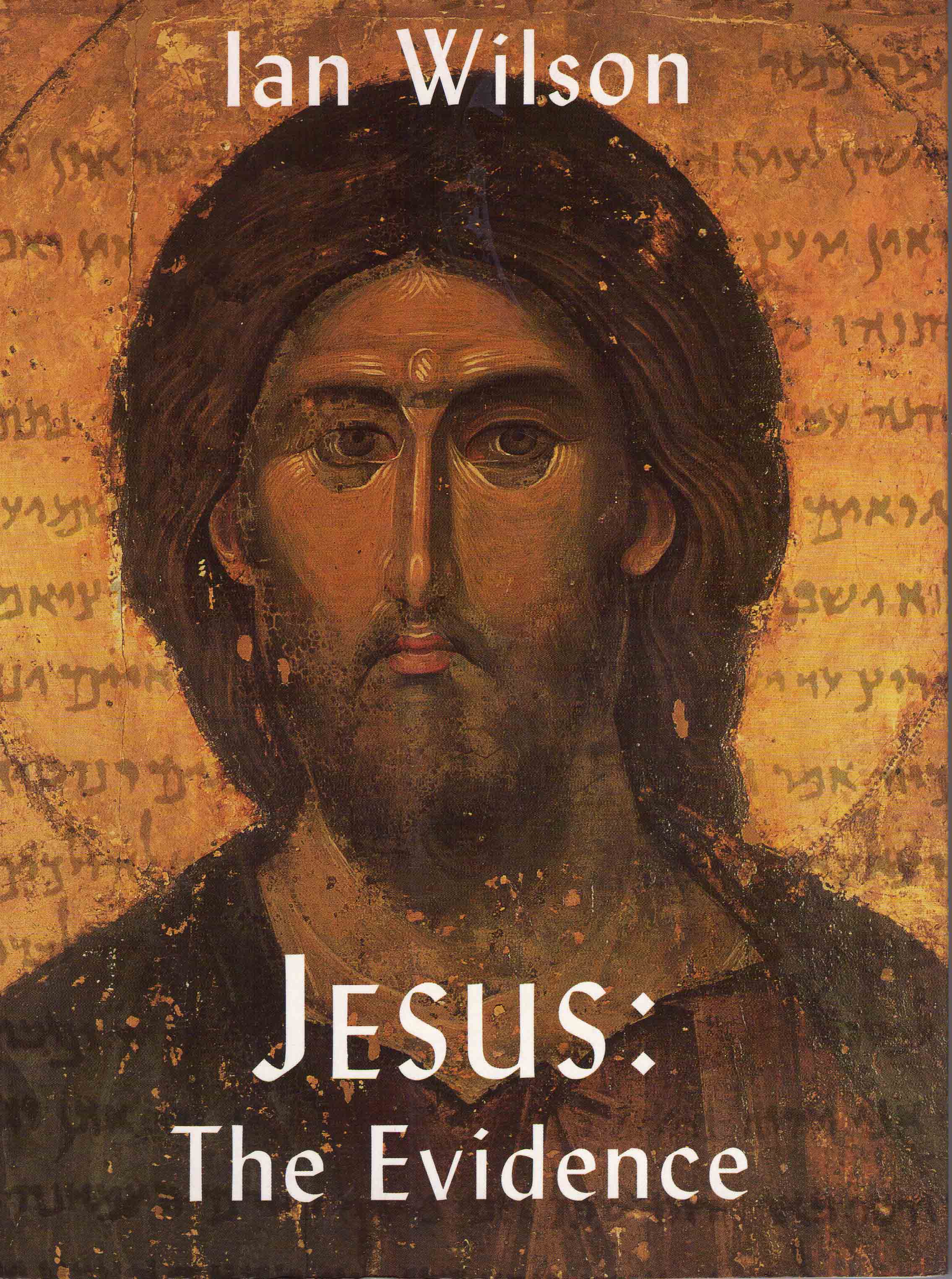

In postmodern “liquid” times words and concepts obtain liquid meanings. One of these words is the compound noun “anti-Semitism.” Anti-Semitism is also a new civil religion that can be used at will for smearing free thinkers. The point is not whether Jesus Christ looked like a proud White Galilean Aryan with a dolichocephalic skull and blond hair—as he is portrayed all over the world—or whether he needs to be pictured with hither-Asian, Semitic features similar to those of Bob Dylan and Bin Laden combined. The issue that needs to be addressed is why Whites, for two thousand years, have adhered to an alien, out-group, non-European conceptualization of the world.