by Tom Holland

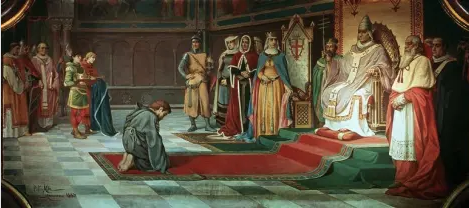

A bare couple of decades after Charlemagne’s death in 814, a Saxon poet, writing in praise of the god brought by the Franks to his people, had contrasted ‘the bright, infinitely beautiful light’ of Christ with the waxing and waning of mortals. ‘Here in this world, in Middle Earth, they come and go, the old dying and the young succeeding, until they too grow old, and are borne away by fate.’ The coronation of Otto in the ancient capital of the world bore potent witness to just how unpredictable were the affairs of men. The throne of empire had stood vacant for over half a century. The last descendant of Charlemagne to occupy it had been deposed, blinded and imprisoned back in 905. The Regnum Francorum, the ‘Kingdom of the Franks’, had fractured into a number of realms. Of these, the two largest were on the western and eastern flanks of the one-time Frankish empire: kingdoms that in time would come to be known as France and Germany. The dynasty to which Otto belonged, and which had been elected to the rule of eastern Francia in 919, had no link to Charlemagne’s. Indeed, it was not even Frankish. Otto the Great, the heir of Constantine, the shield of the West, the wielder of the Holy Spear, was sprung from the very people who, less than two centuries before, had been so obdurate in their defiance of Christian arms: the Saxons…

Meanwhile, in the northern seas, the forces of Christian order were recovering from near implosion. In 937, a great Viking invasion of Britain was defeated by the king of Wessex, a formidable warrior by the name of Athelstan. The triumph, though, was not Athelstan’s alone. For three generations, under his father and grandfather, the West Saxons had been locked in a desperate struggle for survival. They alone, of all the Anglo-Saxon peoples, had managed to preserve their kingdom from Viking conquest—and even then, only just. For a spell, the very future of Christianity in the lands cast by Bede as a new Israel had seemed to hang by a thread. God, though, had saved it from being cut. Not only had the Vikings been brought to submit to Christ, but an entire new Christian kingdom had been built out of the ruins of the old. Athelstan had emerged from a lifetime of relentless campaigning as the first king of a realm that, by the time of his death, stretched from Northumbria to the Channel. ‘Through God’s grace he ruled alone what previously many had held among themselves.’ Redeemed from the brink of disaster, Bede’s vision of the Angles and the Saxons as a single people had been fulfilled.

Great conquerors such as Otto and Athelstan stood in no barbarian’s shadow. After a long century of reverses and defeats, Christian kingship had recaptured its swagger, its mystique. What god could possibly rival the power of the celestial emperor who had brought the Saxons from sinister obscurity to such greatness, or the House of Wessex to feed so many of their foes to the wolves and the ravens? It was only natural for a pagan warlord defeated by Christian arms to ponder this question long and hard. Battle was the ultimate testing-ground of a god’s authority. Not only that, but the rewards of suing for terms from Christ were evident. To accept baptism was to win entry into a commonwealth of realms defined by their antiquity, their sophistication and their wealth. From Scandinavia to central Europe, pagan warlords began to contemplate the same possibility: that the surest path to profiting from the Christian world might not be to tear it to pieces, but rather to be woven into its fabric. Sure enough, two decades after the great slaughter of his people beside the Lech, Géza, the king of the Hungarians, became a Christian. Reproached by a monk for continuing to offer sacrifice ‘to various false gods’, he cheerily acknowledged that hedging his bets ‘had brought him both wealth and great power’. Only a generation on, the commitment to Christ of his son, Waik, was altogether more full-blooded. The new king took the name Stephen; he built churches across the Hungarian countryside; he ordered that the head be shaved of anyone who dared to mock the rites performed within them; he had a rebellious pagan lord quartered, and the dismembered body parts nailed up in various prominent places. Great rewards were quick to flow from these godly measures. Stephen, the grandson of a pagan chieftain, was given as his queen the grand-niece of none other than Otto the Great. Otto’s own grandson, the reigning emperor, bestowed on him a replica of the Holy Spear. The pope sent him a crown. In time, after a long and prosperous reign, he would end up proclaimed a saint.

By 1038, the year of Stephen’s death, the leaders of the Latin Church could view the world with an intoxicating sense of possibility. It was not just the Hungarians who had been brought to Christ. So too had the Bohemians and the Poles, the Danes and the Norwegians. Ambitious chieftains, once they had been welcomed into the order of Christian royalty, were rarely tempted to renew the worship of their ancestral gods. No pagan ritual could rival the anointing of a baptised king. The ruler who felt the stickiness of holy oil upon his skin, penetrating his pores, seeping deep into his soul, knew himself joined by the experience to David and Solomon, to Charlemagne and Otto. Who was Christ himself, if not the very greatest of kings? Over the course of the centuries, he ‘had gained many realms and had triumphed over the mightiest rulers and had crushed through his power the necks of the proud and the sublime’. It was no shame for even the most peerless of kings, even the emperor himself, to acknowledge this. From east to west, from deepest forest to wildest ocean, from the banks of the Volga to the glaciers of Greenland, Christ had come to rule them all.

Yet there was a paradox. Even as kings bowed the knee to him, the hideousness of what he had undergone for humanity’s sake, the pain and helplessness that he had endured at Golgotha, the agony of it all, was coming to obsess Christians as never before. The replica of the Holy Spear sent to Stephen served as a sombre reminder of Christ’s suffering. Christ himself—unlike Otto—had never borne it into battle. It was holy because a Roman soldier, standing guard over his crucifixion, had jabbed it into his side. Blood and water had flowed out. Christ had hung from his gibbet, dead. Ever since, Christians had shrunk from representing their Saviour as a corpse. But now, a thousand years on, artists had begun to break that taboo. In Cologne, above the grave of the archbishop who had commissioned it, a great sculpture was erected, one that portrayed Christ slumped on the cross, his eyes closed, the life gone from his body. Others beheld a similar scene in their visions. A monk in Limoges, rising in the dead of night, saw ‘the image of the Crucified One, the colour of fire and deep blood for half a full night hour’, high against the southern sky, as if planted in the heavens. The closer that 1033, the millennial anniversary of Christ’s death, drew near, so the more did vast crowds, in an ecstasy of mingled yearning, and hope, and fear, begin to assemble. Never before had a movement of such a magnitude been witnessed in the lands of the West. Many gathered in fields outside towns across France, ‘stretching their palms to God, and shouting with one voice, “Peace! Peace! Peace!”, as a sign of the perpetual covenant which they had vowed between themselves and God’. Others, taking advantage of the land-route that the conversion of the Hungarians had opened up, followed the road to Constantinople, and thence to Jerusalem. The largest number of all set out in 1033, ‘an innumerable multitude of people from the whole world, greater than any man before could have hoped to see’. Their journey’s end: the site of Christ’s execution, and the tomb that had witnessed his resurrection.

What were they hoping for? If they declared it, they did so under their breath. Christians were not oblivious to Augustine’s prohibition. They knew the orthodoxy: that the thousand-year reign of the saints mentioned in Revelation was not to be taken literally. In the event, the millennium of Christ’s death came and went, and he did not descend from the heavens. His kingdom was not established on earth. The fallen world continued much as before. Nevertheless, the longing for reform, for renewal, for redemption did not fade. On one level, this was nothing new. Christ, after all, had called on his followers to be born again. The longing to see the entire Christian people purged of their sins had deep roots [bold by Ed.]. It was what, some two and a half centuries previously, had inspired Charlemagne in his great project of correctio. Yet though his heirs still claimed the right to serve as the shepherds of their people, to rule—as Charlemagne had done—as priest as well as king, the ambition to set the Christian world on new foundations was no longer the preserve of courts. It had become a fever that filled meadows with swaying, moaning crowds, and inspired armies of pilgrims to tramp dusty roads…

Arnold was right to foretell upheaval. Much that had been taken for granted was on the verge of titanic disruption. Revolution of a new and irreversible order was brewing in the Latin West. [pages 216-221]