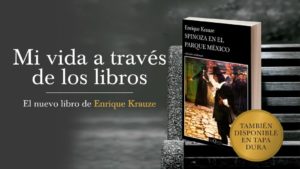

Last Friday I added a short piece on Spinoza in Mexico Park: a book by the Mexican-Jewish Enrique Krauze that I had just bought. Now that I’ve been reading it, I couldn’t resist the urge to write a critical review of it for The Occidental Observer (TOO). My book review has just been published in that webzine for JQ connoisseurs—click: here!

The following is a passage (my translation) of Spinoza in Mexico Park that I could have quoted in my TOO article:

José María Lassalle: In our last conversation we had covered a decade in your intellectual life: that of your integration into Mexican culture as a historian and as editorial secretary of the magazine Vuelta… The one you described in the first conversation with great detail and love: your culture of origin, Jewish culture. I was very surprised by everything you said. I didn’t know that this root was so deep. It almost covered everything… I understand that you wanted to belong to Mexico and to the Hispanic world, and all your life you have worked to achieve it. But secretly you were driven by that initial impulse, by that root. That root is Judaism: the tree grew in Mexico, in Mexican soil, and bore Mexican fruit, but the root and the trunk were Jewish.

Enrique Krauze: What I did was to build that Jewish compound in Amsterdam [obliquely, Krauze is referring to Spinoza, who was born in Amsterdam]… And I began to build a library of Jewish subjects from all eras. A library, above all, of characters and ideas. [pages 419-420]

Latin Americans idolise their intellectuals and writers, so there are a couple of things I’d like to add to what I wrote in the TOO review.

Besides having enormous fame in the Spanish-speaking world, Krauze is one of those serene-speaking ethnic Jews with subtle but toxic messages for the white world. For example, he hasn’t only translated Susan Sontag for the cultural magazines in Spanish he has edited (I have read Krauze since 1990). In Spinoza in Mexico Park, where he talks a lot about WW2, the historian Krauze doesn’t mention David Irving once. Moreover, Krauze writes ‘Holocaust’ in a capital letter and ‘gulag’ in a lowercase in spite of the fact that far more Gentiles died in the Gulag than Jews in the so-called holocaust!

In the TOO piece I only mentioned a few names of the Jewish authors that influenced Krauze, but Spinoza in Mexico Park is replete with other names of historical Jews, from cover to cover. (There is no notable writer in the Spanish-speaking world to point these things out. That’s why I have been calling Latin America the ‘blue pill’ subcontinent.)

On the dilemma that plagues every Westerner—Athens or Jerusalem?—Krauze wrote the following (my translation) about the Greco-Roman world, in the context of Jewish writers of antiquity, such as Josephus and Philo:

[Jewish historian Arnaldo] Momigliano argues that Jerusalem resisted Athens because of the radical religious obstinacy of the people. The Jewish people remained faithful to the priests, the guardians of orthodoxy. For them, Greek culture was synonymous with idolatry, vain pleasures, frivolous comedies, and pagan myths… The Alexandrian Jews tried to persuade the Greek world of the goodness of their faith… One text points to the excesses of a certain Flaccus, the Roman governor in Egypt, who unleashed a veritable pogrom in that city. Even then, this persecution took on the dramatic forms and dimensions that were to be seen many centuries later in the Middle Ages. The profile he [the Jew Momigliano] draws of the delirious Caligula is a jewel worthy of Suetonius [Spinoza in Mexico Park, pages 430-431].

Regular visitors to The West’s Darkest Hour know that this site has a masthead, a guide that allows us to navigate the seas of history. Compare Krauze’s Jewish POV quoted above with the Aryan POV of our ‘masthead’ (pages 33-123 of The Fair Race’s Darkest Hour, linked in our featured post):

In 62-61 b.c.e., the proconsul Lucius Valerius Flaccus (son of the consul of the same name and brother of the consul Gaius Valerius Flaccus) confiscated the tribute of ‘sacred money’ that the Jews sent to the Temple of Jerusalem. The Jews of Rome raised the populace against Flaccus. The well-known Roman patriot Cicero defended Flaccus against the accuser Laelius (a tribune of the plebs who would later support Pompey against Julius Caesar) and referred to the Jews of Rome in a few sentences of 59 b.c.e., which were reflected in his In Defence of Flaccus, XVIII:

‘The next thing is that charge about the Jewish gold… I will speak in a low voice, just so as to let the judges hear me. For men are not wanting who would be glad to excite those people against me and against every eminent man, and I will not assist them and enable them to do so more easily. As gold, under the pretence of being given to the Jews, was accustomed every year to be exported out of Italy and all the provinces to Jerusalem, Flaccus issued an edict establishing a law that…’

From these phrases, we can deduce that already in the 1st century b.c.e., the Jews had great political power in Rome itself and that they had an important capacity for social mobilization against their political opponents, who lowered their voices out of fear: the pressure of the lobbies.

Thus spake Cicero (brown letters) before the senate. The story of the Flaccus family doesn’t end there. In the masthead we then see what happened to another Flaccus[1] in the section about Caligula: another historical figure maligned by Jews and Christians, including the historian Krauze.

Incidentally, I’m in the final proofreading of the November 2022 edition of On Exterminationism, so I won’t be adding more entries here while I work on it. But I’ll answer any questions I am asked about Krauze, whom I met personally—even shook hands with him in 1993!—when he and Octavio Paz published a book by Cuban dissident Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

________

[1] Aulus Avilius Flaccus was appointed praefectus of Roman Egypt from 33 to 38 c.e.