oder: „Mit dem Muttermord an Europa haben die Amerikaner den Scheiterhaufen für sich selbst aufgerichtet“

(Dieser Artikel von Michael O’Meara erschien unter dem Originaltitel „Sommer 1942, Winter 2010: Ein Austausch“ – ins Deutsche übertragen von Albus:)

Im Sommer 1942 – als die Deutschen auf dem Höhepunkt ihrer Kräfte waren und sich des herannahenden Feuersturms, der ihr Land in ein Inferno verwandeln sollte, in keiner Weise bewusst waren – schrieb der Philosoph Martin Heidegger (für eine bevorstehende Vorlesung in Freiburg) die folgenden Zeilen, die ich der englischen Übersetzung entnehme, die als Hölderlins Hymne „Der Ister“ bekannt ist: (*)

„Die angelsächsische Welt des Amerikanismus“ – so Heidegger in einer Nebenbemerkung zu seiner nationalistisch–ontologischen Auseinandersetzung mit seinem geliebten Hölderlin – „hat sich vorgenommen, Europa, das heißt die Heimat, zu vernichten, und das heißt: [sie hat beschlossen,] den Ursprung der westlichen Welt zu vernichten“.

Mit der Vernichtung des Ursprungs (der Anfänge oder des Aufgehens des europäischen Seins) – und somit mit der Vernichtung des Volkes, dessen Blut in den amerikanischen Adern floss – zerstörten die Europäer der Neuen Welt unbewusst das Wesen ihres eigenen Seins, indem sie ihre Ursprünge verleugneten, die Quelle ihrer Lebensform verunglimpften und sich somit die Möglichkeit einer Zukunft versagten.

„Alles, was einen Anbeginn hat, ist unzerstörbar.“

Die Amerikaner haben ihre Selbstzerstörung bestimmt, indem sie ihren Ursprung bekämpften, indem sie die Wurzel ihres Seins abtrennten.

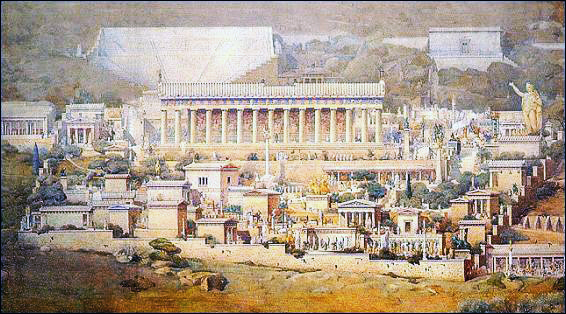

Aber Europa – dieses einzigartige Zusammenwirken von Blut und Geist – kann nicht getötet werden, denn sein Wesen ist, wie Heidegger sagt, der „Anbeginn“ – das Ursprüngliche – das Dasein – die immerwährende Erdung und Neubestätigung des Seins.

Europa erhebt sich wie ihr Stier also immer wieder unweigerlich aus dem Wasser, das sie überspült, während sie sich unerschrocken in das Kommende stürzt.

Ihr letzter Stand ist folglich immer ihr erster Stand – ein weiterer Anbeginn –, da sie zu ihren Ursprüngen vordringt – das unverdorbene Wesen ihres Anbeginns besitzend –, da sie sich in der Fülle einer Zukunft authentifiziert, die ihr ermöglicht, immer wieder neu zu beginnen.

* * *

Das gilt auch für das Gegenteil.

Amerikas Vernichtung seines Ursprungs offenbarte seinen inhärenten Mangel an solchem.

Von Anfang an bestand sein Vorhaben darin, seine europäische Herkunft zu verleugnen – das Wesen zu verleugnen, das es zu dem machte, was es war –, so wie seine Low-Church–Siedler die Metapher der zwei Welten, der alten und der neuen, gebrauchten.

Für Heidegger ist Amerikas „Eintritt in diesen planetarischen Krieg nicht der Eintritt in die Geschichte; vielmehr ist er bereits der ultimative amerikanische Akt amerikanischer Ahistorizität und Selbstzerstörung“.

Denn nachdem Amerika, unbefleckt empfangen, aus der Jeremiade seines puritanischen Auftrags hervorgegangen war, definierte es sich in Ablehnung seiner Vergangenheit, in Ablehnung seiner Ursprünge, in Ablehnung seiner fundamentalsten ontologischen Grundlage – als es westwärts blickte, der Abendsonne und der sich immer weiter ausdehnenden Grenze seiner wurzellosen, flüchtigen Zukunft entgegen, mythisch legitimiert im Namen eines aus der protestantischen Ethik und dem Geist des Kapitalismus heraufbeschworenen „American Dream“.

Der Amerikaner, der durch und durch rationale, wurzellose, uniforme Homo oeconomicus, hat sich nie die Mühe gemacht, nach vorne zu schauen, weil er nie zurückgeblickt hat. Vergangenheit und Zukunft, Wurzeln und Äste – alles abgerissen und abgeschnitten.

Keine Erinnerung, keine Vergangenheit, kein Sinn.

Im Namen des Fortschritts – den sich Friedrich Engels als einen grausamen Wagen vorstellte, der über einen Haufen Leichen fährt – löst sich das amerikanische Wesen in seinem hektischen Vorwärtsdrang in Richtung des schwarzen Abgrunds auf.

Doch wie man es auch dreht und wendet, die Amerikaner kamen aus dem Schoß Europas in die Welt, und nur durch die Bejahung des europäischen Wesens ihres Mutterlandes und ihrer Vaterschaft bestand die Möglichkeit, in ihrer „neuen“ Welt Wurzeln zu schlagen – ohne den Barbaren und Fellachen außerhalb des Mutterbodens und der väterlichen Kultur zu erliegen.

Stattdessen machten sich die Gründer Amerikas daran, ihre Mutter zu verwerfen. Sie nannten sie ägyptisch oder babylonisch und nahmen ihre Identität – als die „Ausersehenen“, die „Auserwählten“, das „Licht für die Völker“ – von den Wüstennomaden des Alten Testaments, denen die großen Wälder unserer nördlichen Länder fremd waren, die neidisch auf unsere blauäugigen, blonden Mädchen blickten und welche die großen, gewölbten Höhen unserer gotischen Kathedralen abstieß.

Dass sie ihr ursprüngliches und einziges Wesen aufgaben, machte die Amerikaner zu den ewigen Weltverbesserern, zu ideologischen Verfechtern der vollkommenen Bedeutungslosigkeit – zur ersten großen „Nation“ des Nihilismus.

* * *

Während Heidegger seinen Vortrag vorbereitete, machten sich Zehntausende von Panzern, Lastwagen und Artilleriegeschützen auf den Weg von Detroit nach Murmansk und dann an die Ostfront der Deutschen.

Kurze Zeit später fielen die Feuer vom Himmel – Feuer, die den Fluch Cromwells und die verbrannte Erde Shermans in sich trugen – Feuer, die deutsche Familien in Asche verwandelten, zusammen mit ihren großen Kirchen, ihren palastartigen Museen, ihren dicht gedrängten, blitzsauberen Arbeitervierteln, ihren uralten Bibliotheken und hochmodernen Laboratorien.

Der Wald, der tausend Jahre brauchte, um zu werden, vergeht in einer Nacht voller Phosphorflammen.

Es würde lange dauern – es ist noch nicht so weit –, bis die Deutschen, das Volk der Mitte, das Zentrum des europäischen Seins, wieder aus den Trümmern auferstehen, diesmal mehr geistig als materiell.

* * *

Heidegger konnte wenig von dem apokalyptischen Sturm wissen, der im Begriff war, sein Europa zu zerstören.

Aber ahnte er wenigstens, dass der Führer Deutschland in einen Krieg verwickelt hatte, den es nicht gewinnen konnte? Dass nicht nur Deutschland, sondern auch das Europa, das sich den anglo-amerikanischen Mächten des Mammons entgegenstellte, zerstört werden würde?

* * *

„Der verborgene Geist des Aufbruchs im Westen wird nicht einmal den Blick der Verachtung für diesen Selbstzerstörungsversuch ohne Aufbruch haben, sondern aus der Erleichterung und Ruhe heraus, die zum Aufbruch gehören, seine Sternstunde abwarten.“

Ein erwachtes, neu beginnendes Europa verspricht also, Amerikas Verrat an sich selbst zurückzuweisen – Amerika, diese törichte, von aufklärerischer Hybris durchdrungene europäische Idee, die (wie eine Familienschmach) in Vergessenheit geraten soll, sobald Europa sich wieder aufrichtet.

1942 wusste Heidegger jedoch nicht, dass sich die Europäer, selbst die Deutschen, bald an die Amerikaner verraten würden, als die Churchills, Adenauers und Blums – Europas Speichellecker – an die Spitze der Nachkriegspyramide der Yankees aufstiegen, die jede Idee von Nation, Kultur und Schicksal zerschlagen sollte.

Das ist die Tragödie Europas.

* * *

Erwacht Europa – und das wird eines Tages der Fall sein –, wird es sich wieder selbst bestätigen und sich behaupten, nicht mehr abgelenkt von Amerikas Glitzer und Flitter, nicht mehr eingeschüchtert von seiner Wasserstoffbombe und seinen Lenkraketen, sondern endlich klar erkennend, dass sich hinter dieser hollywoodesken Unterhaltung eine ungeheure Leere verbirgt – endlose Übungen in vollendeter Bedeutungslosigkeit.

Unfähig, neu anzufangen, weil sie sich selbst den Anbeginn verweigert hat, wird die schlechte Idee, zu der Amerika geworden ist, im kommenden Zeitalter von Feuer und Stahl in ihre Einzelteile zerfallen.

In diesem Moment werden die weißen Amerikaner aufgerufen sein, als Europäer der Neuen Welt ihr „Recht“ auf ein Heimatland in Nordamerika geltend zu machen – damit sie dort endlich einen Platz haben, an dem sie sein können, wer sie sind.

Sollte ihnen dieses anscheinend unerreichbare Glück gelingen, werden sie zum ersten Mal die amerikanische(n) Nation(en) gründen – und zwar nicht als das universelle Simulakrum, das Freimaurer und Deisten 1776 zusammengebraut haben, sondern als das Geblüt des amerikanischen Schicksals Europas.

„Wir denken das Geschichtliche in der Geschichte nur halb, das heißt, wir denken es gar nicht, wenn wir die Geschichte und ihre Größe nach der Länge … des Gewesenen berechnen, anstatt das Kommende und Zukünftige zu erwarten.“

Der Anbeginn als solcher ist „das Kommende und Zukünftige“ – das „Historische in der Geschichte“ –, das sehr weit zurückreicht und in jede ferne, sich entfaltende Zukunft hineingetragen wird – wie Picketts gescheiterter Infanterieangriff in Gettysburg, der, wie Faulkner sagt, immer wieder versucht werden soll, bis er gelingt.

* * *

„Wir stehen erst dann am Anbeginn der eigentlichen Geschichtlichkeit, d. h. des Handelns im Bereich des Wesentlichen, wenn wir in der Lage sind, auf das zu warten, was aus dem Eigenen bestimmt werden soll.“

Das „Eigene“ – diese Selbstbehauptung – wird, so Heidegger, nur dann eintreten, wenn wir uns über Konformität, Konvention und unnatürliche Konditionierung hinwegsetzen, um das europäische Wesen zu verwirklichen, dessen Bestimmung allein die unsere ist.

In diesem Moment, wenn es uns gelingen sollte, aufrecht zu stehen, wie es unsere Vorfahren taten, werden wir nach vorne und darüber hinaus zu dem reichen, was durch jede futuristische Bejahung dessen, was wir Europäer-Amerikaner sind, begonnen wird.

Dieses Ausgreifen wird jedoch kein „handlungs- oder gedankenloses Kommen- und Gehenlassen der Dinge sein … [sondern] ein Stehen, das bereits vorausgesprungen ist, ein Stehen in dem, was unzerstörbar ist (zu dessen Nachbarschaft die Verwüstung gehört, wie ein Tal zu einem Berg)“.

Denn die Verwüstung wird – in diesem Kampf, der auf unseresgleichen wartet – in dieser bestimmten Zukunft trotzig eine Größe aushalten, die nicht zerbricht, während sie sich im Sturm biegt – eine Größe, die mit der Gründung einer europäischen Nation in Nordamerika sicher kommen wird – eine Größe, von der ich oft befürchte, dass wir sie nicht mehr in uns haben und die deshalb in den feurigen Kriegerriten beschworen werden muss, die einst an die alten arischen Himmelsgötter erinnerten, wie weit entfernt oder fiktiv sie auch geworden sind.

– Winter 2010

Anmerkung

_________

(*) Martin Heidegger, Hölderlin’s Hymn „The Ister“, übers. von W. McNeill und J. Davis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), S. 54 ff.