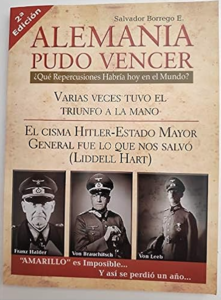

by Salvador Borrego

Worse than 5th century Attila

When the bombing of German residential areas was at its height, wounding thousands of women and children, Pope Pius XII requested that the Allied powers designate a German city as a ‘hospital city’ where the wounded could be cared for and sheltered from the bombing. Churchill did not deign to reply. By contrast, in 452 the dreaded Attila, king of the Huns, was looming over Rome, and Pope Leo I (called the Great) went out to meet him and said something to him. It is not known what, but Attila retreated unharmed.

Visibly more intractable than Attila, the ‘civilised’ Winston Churchill made decisions without the slightest trace of humanity, one might even say with complacency. For example, on learning that German Red Cross seaplanes were rescuing pilots floating in the waters of the English Channel, he ordered them to be fired upon. The rescue was of German and British pilots, but Churchill felt that the German airmen could return to combat. What about the British? If they were saved, they would be taken prisoner, so that they would be of no further use to Britain. Their lives did not matter.

Savage warfare was also fought at sea. Just one example: the German submarine U-156, commanded by Captain Werner Hartenstein, sank the 20,000-ton British-flagged armed merchant cruiser ‘Laconia’. When Hartenstein realised that there were many shipwrecked survivors, more than 200 Englishmen, including civilians, he began to rescue them and called two more submarines to help him. At the same time, he radioed his position on marine frequencies in English for help from the British Navy. The three submarines would not fire and identified themselves as the Red Cross.

Meanwhile, the castaways continued to swell, crowding the U-boats’ interiors and decks, and the submarines were towing several lifeboats. As the U-boats were struggling to care for the shipwrecked, several American tetra-motors finally appeared, but to their surprise, they were dropping bombs on the three U-boats, which were forced to submerge.

Did London think it was more ‘profitable’ to sink a submarine than to save its shipwrecked sailors? Of the 811 Englishmen on board the Laconia, 800 were saved. And of the 1,800 Italian prisoners on board, only 450 could be saved.

Hess’ offering peace—a ‘war crime’

After defeating France and the British expeditionary army, Hitler made two peace offers to Britain, asking for nothing in return. Churchill responded contemptuously. Then Rudolf Hess, head of the National Socialist Party and Hitler’s successor after Goering, made a risky flight to England to give more impetus to a third peace attempt. Churchill would not allow him to speak to the King and imprisoned him as a ‘war criminal’. He was later tried at Nurenberg and sentenced to life imprisonment. At the age of 93, aged and infirm, he was asphyxiated with a wire and it was called ‘suicide’. His remains were buried at an unknown location.

For centuries it had been customary for a white-flagged peace emissary to be listened to and then returned to his home territory, whether anything or nothing was approved. It was more practical for Churchill to declare him a war criminal, even though Hess took no part in the war. His flight took place on the eve of the German attack on the USSR.

Incidentally, Churchill, so ‘gentlemanly’, sympathised with Stalin (whom Roosevelt called ‘Uncle Joseph’), and before the war he watched impassively as the USSR took over fifteen Asian countries, with fifty million inhabitants and five million square kilometres, to subject them to communism. And during Stalin’s mass purges of opponents or mere suspects, Churchill played them down as ‘not entirely unnecessary’. The secret is that in the world there is one entity with two arms: the right one in Wall Street and London, and the left one in Moscow. The two have merged into Liberalism and savage Neoliberalism, heading towards World Government, which in turn is innocently presented as Globalisation.

Eleven million inhabitants thrown out of their homes and territory

This happened as a result of German provinces being given to Poland and the USSR, according to Churchill’s decision.

In the Atlantic Charter, signed on 14 August 1941 by Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin, it was specified that none of the three belligerents would seek territory from the defeated. But at the end of the war, it was stated that this pact did not include Germany. As a result, several provinces in eastern Germany were to be ceded to Poland and the USSR. Their 15 million inhabitants were to be thrown out, with only the clothes on their backs.

Of those 15 million, four million managed to flee months before the end of the war, due to the invasion of Soviet troops, who had been supplied with extra vodka by the Jewish commissar llia Eherenburg and the slogan to ‘humiliate German women’ using mob rapes.

It remained, then, to displace eleven million inhabitants. The Russian writer Solyenitsin writes that ‘the savagery committed by the Soviet troops seemed to be a decoration won in combat’. Some towns occupied by the Red Army were temporarily retaken by German troops, and they witnessed so many crimes against the civilian population that press correspondents from neutral countries such as Switzerland, Sweden, Spain and even France were called in as witnesses. Geneva’s Le Curier reported on 7 November 1944 that there were scenes that were hard to believe if you did not see them. A caravan of women and children trying to escape had been crushed by the tracks of Soviet tanks. The enemy raped girls as young as seven and women as old as 80, and those who put up desperate resistance were hanged and still raped. In small villages, not a woman or girl or old man was left alive. There had been numerous suicides. An estimated 1.5 million girls and adult women were raped.

On 28 December 1944, when the savagery of the Soviets had been fully established, Pope Pius XII publicly condemned it, but no one seconded him. The mainstream press hushed up the whole thing or alluded to it only tangentially in brief notes.

Churchill authorised the ‘transfers’

On 15 December 1945, Churchill reiterated in the House of Commons: ‘Expulsion is the method which, so far as we can foresee, will prove most satisfactory and lasting. And I am not concerned with these mass deportations which, under modern conditions, are now more practicable than ever.

Already the Earl of Mansfield had prepared the ground for Churchill in the House of Commons with the following ‘reasoning’: ‘There is no reason why we should look with undue consternation on the inevitable sufferings which may be inflicted on the Germans in the course of these transfers’.

Since such transfers were more difficult in the middle of winter, as there were no vehicles on land and the displaced persons were forced to walk long distances on foot, the German navy wanted to help. On the liner Wilhelm Gustloff, 10,500 people were crammed onto the ship on 30 January 1945. It was a ship identified as a Red Cross ship, as it was carrying women, children and wounded. Yet it was torpedoed and sunk by a Soviet submarine. Almost all died in the icy waters.

Twelve days later the hospital ship Steuben, with 3,608 civilians on board from East Prussia, which the Allies were cutting off from Germany to give to the USSR, met the same fate. Days later, a third hospital ship, the Goya, was also sunk with 6,667 civilians on board. Together, the three sinkings killed 20,000 adults and children, thirteen times more than those who died in the Titanic tragedy of 1912. Captain Marinesko, commander of the submarine that carried out two of the three sinkings, was declared a hero of the Soviet Union.

But, of course, as the English Earl Mansfield had said, ‘There is no reason why we should look with undue consternation on the inevitable sufferings which may be inflicted on the Germans in the course of the transfers’.

A dismayed US senator

When the mass expulsion was already in full swing, a group of US senators went to observe what was happening. They saw how people were forced to leave their homes, their furniture and their land. They could only take what they were wearing. Mr Eastland then reported to the US Senate: ‘It is one of the most horrible chapters in human history. Words are incapable of adequately describing what is going on there. The virtue of humanity and the value of human life are the most sacred possessions of civilised man. Yet they are today the most trivial thing in East Germany. Conditions prevail there which defy human comprehension’ (4 Dec. 1945).

Another who was also dismayed was the British MP Evans, who denounced in the House of Commons that the expulsions ‘are a great tragedy, indescribable and revolting. Is it for this that the souls of the brave, of those who did not return, of those who could not grow old, have died in this war?’

Moreover, a British officer, a witness to the expulsion, said: ‘The greatest horror in contemporary history is taking place in East Germany. Many millions of Germans—mostly women and children—have been thrown on the roads and are dying by the thousands on those roads from starvation, dysentery and exhaustion’ (14 Nov. 1946). Summing up what he had seen in turn, US Congressman Mr Eastlan declared: ‘It is a crime of genocide’.

It was remarkable, at the time, how unanimous the international news agencies were in silencing or ignoring the protests in Britain and the United States about the cruelty of the expulsions.

From his point of view as a geographer, the American Isaiah Bowman—who participated in the San Francisco Peace Conference when the transfers were taking place—said: ‘One’s territory evokes personal and group feelings. For a people, it is in its soil that the traces of its past reside. A people endows their territory with a mystical nature where the echo of its ancestors resounds. The authors of old deeds speak to their people from their graves dug in their soil. The landscape is essential to the concept of home’. This is how this scientist saw the tragedy of the millions of Germans forced to lose the soil of their ancestors, and that nine million adults and children could hardly be accommodated in West Germany.

Even in the House of Commons in London there was criticism of such expulsions as inhumane, to which Churchill responded as follows: ‘Since seven million Germans died in the war, there is now sufficient space to receive at least as many displaced people from the eastern territories, thus restoring everything to its former equilibrium’. Not even Attila used to make such ‘transfers’!

Psychological enigma: Churchill and Eisenhower

Psychological enigma: Churchill and Eisenhower