I read ‘Nietzsche’s Der Antichrist: Looking Back From the Year 100’ in late 1993, in a hard copy issued in the winter of 1988/1989: one of the back copies of Free Inquiry that arrived in the mail when I discovered that organisation of freethinkers.

I met the author, Robert Sheaffer, at the 1994 CSICOP conference. If memory serves, he wore sandals, was dressed casually and had a beard. Last year I exchanged some correspondence with him.

Sheaffer is anything but a Hitlerite. However, the article that I abridge below is perfect for understanding a central part of esoteric Hitlerism. I mean that Uncle Adolf’s anti-Christianity, which wasn’t revealed to the masses of Germans (hence the epithet ‘esoteric’), already had antecedents in Germany.

Sheaffer’s complete article can be read here. Red emphasis is mine:

______ 卐 ______

Secular humanists have not infrequently criticized the beliefs and practices of the Christian religion, and its harmful effects on civilization and culture. Unfortunately, their voice is seldom heard. The proponents of the Christian world-view vastly outnumber secularists both in number and in activity. While humanists wonder what they they can do to more effectively convey their criticisms of religion, most of them have never read, and indeed have barely even heard of, a book written exactly a century ago containing the most devastating and complete philosophical attack on Christian psychology, Christian beliefs and Christian values ever written: Nietzsche’s Der Antichrist.

1888 was the final productive year of the life of Friedrich Nietzsche, but it was a year of incredible activity. He wrote five books during a six-month period in the latter part of that year. After that, he wrote nothing. Nietzsche’s works of 1888 have not received enough attention, especially given the inclination of many to concentrate primarily on the flamboyant and somewhat confusing Also Spracht Zarathustra, a book of intricate allegories and parables which requires that one already understand the principal elements of Nietzschean thought in order to decipher its hidden relationships and meanings. Zarathustra will be clearer if it is read at the end of a course of study of Nietzsche, not at the beginning.

The first book of 1888 was The Case of Wagner, in which Nietzsche set forth his aesthetic and philosophical objections to the music and the writings of his former close friend Richard Wagner… Next came The Twilight of the Idols (in German, Die Gotzen-dammerung, an obvious parody of Wagner’s Die Gotterdammerung, “The Twilight of the Gods”), in which he criticizes romanticism, Schopenhauer’s pessimism, German culture, Socrates’ acceptance of death as a “healing” of the disease of life, Christianity, and a good many other things. Then, in September of 1888, Nietzsche wrote Der Antichrist.

Unlike Zarathustra, there can be no mistaking the language or the intention of Der Antichrist, a work of exceedingly clear prose and seldom-equalled polemics. Even today, the depth of Nietzsche’s contempt for everything Christianity represents will surprise and shock many people, and not only devout Christians. Unlike other critics of religion, Nietzsche’s attack extends beyond religious theology to Christian-derived concepts that have spread out far beyond their ecclesiastical origins, to the very core of the value-system of Western, Christianized society.

Der Antichrist begins with a warning that “This book belongs to the very few,” perhaps to no one yet living. Nietzsche hints that only those who have already mastered the obscure symbolism of his Zarathustra could appreciate this work. Warnings aside, he begins by sketching the idea of declining vs. ascending life and culture. An animal, a species, or an individual is “depraved” or “decadent” when it loses its instincts for that which sustains its life, and “prefers what is harmful to it.” Life itself presupposes an instinct for growth, for sustinence, for “the will to power”, the striving for some degree of control and mastery of one’s surroundings. Christianity sets itself up in opposition to those instincts, and hence Christianity is an expression of decadence, a negation of the will to life [Antichrist, section 6].

“Pity”, says Nietzsche, is “practical nihilism”, the contagion of suffering. By elevating pity to a value—indeed, the highest value—its depressive effects thwart those instincts which preserve life, establishing the deformed or the sick as the standard of value. [A 7] To Nietzsche, the rejection of pity did not proscribe generosity, magnanimity, or benevolence—indeed, the latter are mandated for “higher” types—; what is rejected is to allow the ill-constituted to define what is good. Nietzsche was not hostile to the sick—Zarathustra bids the sick to “become convalescents”, and expresses sympathetic understanding of their unhappy frame of mind [Z I 3]—but what he opposed was the use of the existence of sickness and other afflications to thereby claim “life is refuted” [Z I 9].

No doubt Nietzsche’s attack on “pity” was triggered in part by his revulsion against Wagner’s blatantly irrational opera Parsifal, in which the formerly irreligious Wagner returned once again to pious Christian themes. In Parsifal, a series of calamities occur because a once-holy knight succumbs to “sins of the flesh,” and it is prophesied that the situation cannot be remedied by any act of self-directed effort, but only by one “through pity made wise, a pure fool.” Nietzsche’s contempt for the limp Christianity in Parsifal and for “the pure fool” knew no bounds. The already-strained bond between the two men, who were once extremely close, was irreparably broken.

Nietzsche explains that the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer is, like Chrisitanity, decadent. Schopenhauer taught that since it is impossible to satisfy the desires of the will, one must ceaselessly renounce striving for what one wants, and become resigned to unhappiness. In the late 19th century Schopenhauer’s doctrines were extremely popular, especially among the Wagnerians. Wagner’s monumental Tristan and Isolde is an expression of Schopenhauerian nihilism, as the lovers sing of the impossibility of earthly happiness, and of their expected mystical union in the realm of “night” after their death. The opera closes with Isolde’s famous liebestod, or “love-death”, as she sings of a vision of her dead lover gloriously and mystically transfigured in the nether-regions, then dies to join him. Schopenhauer was hostile to life, says Nietzsche, “therefore pity became for him a virtue.” [A 7]

Nietzsche charges that Christianity denigrates the world around us as mere “appearance”, a position grounded in the philosophy of Plato and Kant, and hence invents a “completely fabricated” world of pure spirit. However, “pure spirit is pure lie,” and hence the theologian requires one to see the world falsely in order to remain a member in good standing in the religion. The Christian outlook was, he says, immensely bolstered against the attacks of the Enlightenment by Immanuel Kant, whose philosophy renders reality unknowable. (For Kant a virtue is something harmful to one’s life, a view Nietzsche could never accept. If you want to do something, Kant would say your action cannot possibly be virtuous; any action which contains an element of self-interest is by definition not virtuous.) Nietzsche summarizes, “anti-nature as instinct, German decadence as philosophy—that is Kant.” [A 8-11]

Nietzsche praises the skeptic (or “free spirit”) who rejects the priestly inversion of “true” and “untrue”. He says we skeptics no longer think of human life as having its origins in “spirit” or in “divinity”, but recognize the human race as a natural part of the animal kingdom… [A 12-14].

Returning to the theme of Christian doctrine as misrepresentation, Nietzsche charges that “in Christianity neither morality nor religion come into contact with reality at any point.” The religion deals with imaginary causes (such as God, soul, spirit) and imaginary effects (sin, grace, etc.), and the relationships between imaginary beings (God, souls, angels, etc.). It also has its own imaginary natural science (wholly anthropormorphic and non-naturalistic), an imaginary human psychology (based on repentance, temptation, etc.), as well as an imaginary teleology (apocalypse, the kingdom of God, etc.). Nietzsche concludes that this “entire fictional world has its roots in the hatred of the natural” world, a hatred which reveals its origin. For “who alone has reason to lie himself out of actuality? He who suffers from it” [A 15]. Here is the proof which convinced Nietzsche that Christianity is not only decadent in its origins, but rotten to its very core: no one reasonably satisfied with his own mind and abilities would wish to see the real world replaced with a lie.

Comparing religions, Nietzsche came to the conclusion that in a healthy society, its gods represent the highest ideals, aspirations, and sense of competence of that people. For example, Zeus and Apollo were obviously powerful ideals for Greek society, an image of the mightiest mortals projected into the heavens. Such gods are fully human, and display human strengths and weaknesses alike. The Christian God, however, shows none of the normal human attributes and appetites. It is unthinkable for this God to desire sex, food, or even openly display revengefulness (as did the Greek gods). Such a God is clearly emaciated, sick, castrated, a reflection of the people who invented him. If a god symbolizes a people’s perceived sense of impotence, he will degenerate into being merely “good” (an idealized image of the kind master, as desired by all slaves), void of all genuinely human attributes. The Christian God represents the “divinity of decadence,” the reduction of the divine into a God who is the contradiction of life. Those impotent people who created such a God in their own image do not wish to call themselves “the weak,” so they call themselves “the good.” [A 16-19].

Comparing religions, Nietzsche came to the conclusion that in a healthy society, its gods represent the highest ideals, aspirations, and sense of competence of that people. For example, Zeus and Apollo were obviously powerful ideals for Greek society, an image of the mightiest mortals projected into the heavens. Such gods are fully human, and display human strengths and weaknesses alike. The Christian God, however, shows none of the normal human attributes and appetites. It is unthinkable for this God to desire sex, food, or even openly display revengefulness (as did the Greek gods). Such a God is clearly emaciated, sick, castrated, a reflection of the people who invented him. If a god symbolizes a people’s perceived sense of impotence, he will degenerate into being merely “good” (an idealized image of the kind master, as desired by all slaves), void of all genuinely human attributes. The Christian God represents the “divinity of decadence,” the reduction of the divine into a God who is the contradiction of life. Those impotent people who created such a God in their own image do not wish to call themselves “the weak,” so they call themselves “the good.” [A 16-19].

Nietzsche next compares Christianity to Buddhism. Both, he says, are religions of decadence, but Buddhism is a hundred times wiser and more realistic. Buddha does not demand prayer or aesceticism, demanding instead ideas which produce repose or cheerfulness. Buddhism, he says, is most at home in the higher and learned classes, while Christianity represents the revengeful instincts of the subjugated and the oppressed. Buddhism promotes hygiene, while Christianity repudiates hygiene as sensuality. Buddhism is a religion for mature, older cultures, for persons grown kindly and gentle—Europe is not nearly ripe for Buddhism. Christianity, however, tamed uncivilized barbarians, needing to subjugate wild “beasts of prey,” who cannot control their own “will to power.” The way it did so was to make them sick, making them thereby too weak to follow their destructive instincts. Thus Buddhism is a religion suited to the decadence and fatigue of an ancient civilization, while Christianity was useful in taming barbarians, where no civilization had existed at all. [A 20-22].

Nietzsche next emphasises Christianity’s origin in Judaism, and its continuity with Jewish theology. He was fond of pointing out the essential Jewishness of Christianity as a foil to the anti-Semites he so despised, effectively taunting them, “you who hate the Jews so, why did you adopt their religion?”. It was the Jews, he asserts, who first falsified the inner and outer world with a metaphysically complete anti-world, one in which natural causality plays no role. (One might of course object that such a concept considerably predates Old Testament times.) The Jews did this, however, not out of hatred or decadence, but for a good reason: to survive. The Jews’ will for survival is, he asserts, the most powerful “vital energy” in history, and Nietzsche admired those who struggle mightily to survive and prevail. As captives and slaves of more powerful civilizations—the Babylonians and the Egyptians—the Jews shrewdly allied themselves with every “decadence” movement, with everything that weakens a society, not because they were decadent themselves, but in order to weaken their oppressors. Thus, Nietzsche views the Jews as shrewdly inculcating guilt, resentment, and other values hostile to life among their oppressors as a form of ideological germ warfare, taking care not to become fully infected themselves. This technique was ultimately successful in defeating stronger parties—Babylonians, Egyptians, and Romans—by in essence making them “sick,” and hence less powerful. (The Romans, of course, succumbed to the Christian form of Judaism, in this view.) This parallels St. Augustine’s comment, quoting Seneca, that the Jews “have imposed their customs on their conquerors.” [A 23-26; De Civitate Dei VI 11]

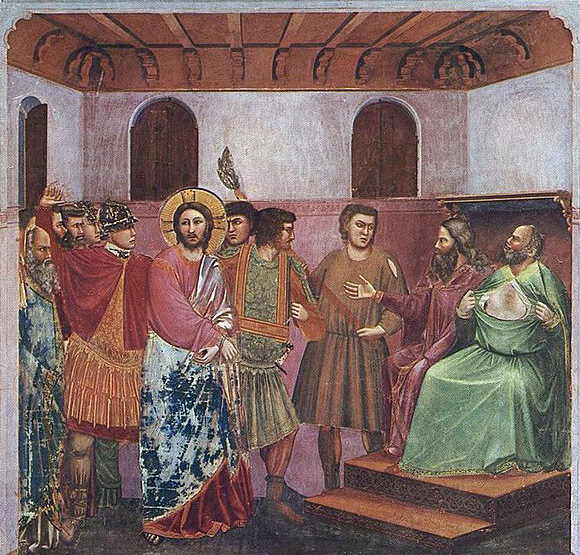

“On a soil falsified in this way, where all nature, all natural value, all reality had the profoundest instincts of the ruling class against it, there arose Christianity, a form of mortal hostility to reality as yet unsurpassed.” The revolt led by Jesus was not primarily religious, says Nietzsche, but was instead a secular revolt against the power of the Jewish religious authorities. The very dregs of Jewish society rose up in “revolt against ‘the good and the just’, against ‘the saints of Israel’.” This was the political crime of Jesus, a crime of which he was surely guilty, and for which he was crucified. Nietzsche examines the psychology of Jesus, as is best possible from the Biblical accounts, and detects a profound sense of withdrawl: resist not evil, the kingdom of God is within you, etc. He sees parallels in the psychology of Christ not with some hero, but with Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. (Dostoyevsky is not mentioned here by name, but we know from other sources that this is the “idiot” Nietzsche had in mind.)

Nietzsche deduces that the earliest Christians sought to retreat into a state of extreme withdrawl from “the world”, undisturbed by reality of any kind. They rejected all strong feelings, favorable or otherwise. Their fear of pain, even in infinitely small amounts, “cannot end otherwise than in a religion of love.” Thus Nietzsche sees early Christianity as promoting an extremely dysfunctional state resembling autism, a defense mechanism for those who cannot deal with reality. Noting Christianity’s claims to deny the world, and its stand in opposition to every active virtue, Nietzsche asks how can any person of dignity and accomplishment not feel ashamed to be called a Christian? [A 27-30; 38]…

By placing the center of life outside of life, in “the beyond”, Nietzsche says we deprive life of any focus or center whatsoever. The invention of the immortal soul automatically levels all rank in society: “‘immortality’ conceded to every Peter and Paul has so far been greatest, the most malignant attempt to assassinate noble humanity”. Thus “little prigs and three-quarter madmen may have the conceit that the laws of nature are constantly broken for their sakes,” thereby obiliterating all distinctions grounded in merit, knowledge or accomplishment. Christianity owes its success to this flattering of the vanity of “all the failures, all the rebellious-minded, all the less favored, the whole scum and refuse of humanity who were thus won over to it.” For Christianity is “a revolt of everything that crawls upon the ground directed against that which is elevated: the gospel of the ‘lowly’ makes low.” Here we clearly see Nietzsche’s repudiation of Christianity’s attitudes as well as its theology: as he pointedly noted in Ecce Homo, “no one hitherto has felt Christian morality beneath him”. All others saw it as an unattainable ideal. [A 43; EH 4 (“Why I Am a Fatality”) 8] Pre-Christian thinkers did not, of course, see poverty as suggestive of virtue, but rather of its absence. One point Nietzsche was unable to either forgive or forget was that the enemies of the early Christians were “the intelligent ones”, persons far more civilized, erudite, and accomplished than themselves, people who Nietzsche felt more fit to rule than the Christians.

Nietzsche sees the Gospels as proof that corruption of Christ’s ideals had already occurred in those early Christian communities. They say “Judge Not!”, then send to Hell anyone who stands in their way. Arrogance poses as modesty. He explains how the Gospel typifies the morality of ressentiment ( a French term Nietzsche used in his German texts), a spirit of vindictiveness and covert revengefulness common among those who are seething with a sense of their own impotence, and hence must hide their desire for vengeance. “Paul was the greatest of all apostles of revenge,” writes Nietzsche [A 44-45]…

At this point, Nietzsche advises the reader to “put on gloves” when reading the New Testament, because one is in proximity to “so much uncleanliness.” It is impossible, he says, to read the New Testament without feeling a partiality for everything it attacks. The Scribes and the Pharisees must have had considerable merit, to have been attacked by the rabble in such a manner. Everything the first Christians hate has value, for theirs is the unthinking hatred of the rabble for everyone who is not a wretched failure like themselves. Nietzsche sees Christianity’s origins in what Marxists would call “class warfare,” and sides with those possessing learning and self-discipline against those having neither. [A 46].

He next turns to a point essential for the understanding of Nietzschean thought: the inevitability of a “warfare” between Christianity and science. Because Christianity is a religion which has no contact with reality at any point, it “must naturally be a mortal enemy of ‘the wisdom of the world,’ that is to say, of science.” Here “science” is not to be understood as merely the physical sciences, but as any rigorous and disciplined field of human knowledge, all of which are potentially threats to Christian dogma. Hence Christianity must calumniate the “disciplining of the intellect” and intellectual freedom, bringing all organized secular knowledge into disrepute; for “Paul understood the need for the lie, for faith.” Nietzsche refers to the Genesis fable of Eve’s temptation, asking whether its significance has really been understood: “God’s mortal terror of science”? The priest perceives only one great danger: the human intellect unfettered. Continuing the metaphor of science as eating from the tree of knowledge:

Science makes godlike—it is all over with priests and gods when man becomes scientific. Moral: science is the forbidden as such—it alone is forbidden. Science is the first sin, the original sin. This alone is morality “Thou shalt not know”—the rest follows.

The priest invents and encourages every kind of suffering and distress so that man may not have the opportunity to become scientific, which requires a considerable degree of free time, health, and an outlook of confident positivism. Thus, the religious authorities work hard to make and keep people feeling sinful, unworthy, and unhappy. [A 47-49]

In previous works, Nietzsche had emphasised the necessity of struggling hard to uncover truth, of preferring an unpleasant truth to an agreeable delusion. [The Gay Science 344; Beyond Good and Evil 39] Consequently, he sees another reason for being suspicious of Christianity in its notion that “faith makes blessed,” that is, creates a state of pleasure in harmony with God. He re-iterates that whether or not a doctrine is comforting tells us nothing about its truth. Nor does the willingness of martyrs to suffer and die for a belief constitute any proof of veracity, suggesting that a visit to a madhouse will suffice to demonstrate the fallaciousness of such arguments. Martyrdoms have, in fact, been a great misfortune throughout history because “they have seduced” us into questionable doctrines. “Blood is the worst witness of truth”. [A 50-51, 53]

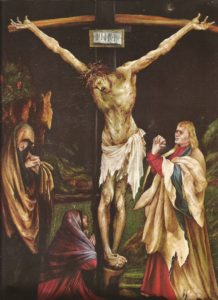

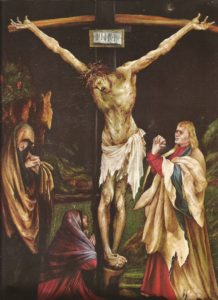

Christianity, says Nietzsche, needs sickness as much as Hellenism needed health. (To understand this point, compare a Greek statue of a tall, handsome, naked God with a Christian religious image of an unhygenic, slovenly figure suffering greatly.) One does not “convert” to Christianity, but rather one must be made “sick enough” for it. The Christian movement was, from its beginning, “a collective movement of outcast and refuse elements of every kind,” seeking to come to power through it. “In hoc signo decadence conquered.” Christianity also stands in opposition to intellectual, as well as physical, health. To doubt becomes sin. Nietzsche defines faith as “not wanting to know what is true,” a description which strikes me as stunning, and quite exact. [A 51-52]…

Christianity, says Nietzsche, needs sickness as much as Hellenism needed health. (To understand this point, compare a Greek statue of a tall, handsome, naked God with a Christian religious image of an unhygenic, slovenly figure suffering greatly.) One does not “convert” to Christianity, but rather one must be made “sick enough” for it. The Christian movement was, from its beginning, “a collective movement of outcast and refuse elements of every kind,” seeking to come to power through it. “In hoc signo decadence conquered.” Christianity also stands in opposition to intellectual, as well as physical, health. To doubt becomes sin. Nietzsche defines faith as “not wanting to know what is true,” a description which strikes me as stunning, and quite exact. [A 51-52]…

Nietzsche now turns to consider why the lie is told. Once again, Christian teachings are compared to those of another religion, that of Manu, “an incomparably spiritual and superior work.” Unlike the Bible, the Law-Book of Manu is a means for the “noble orders” to keep the mob under control. Here, human love, sensuality, and procreation are treated not with revulsion, but with reverence and respect. After a people acquires a certain experience and success in life, its most “enlightened,” most “reflective and far-sighted class” sets down a law summarizing its formula for success in life, which is represented as a revelation from a deity, for it to be accepted unquestioningly. Such a set of rules is a formula for obtaining “happiness, beauty, benevolence on earth.” This aristocratic group considers “the hard task a privilege… life becomes harder and harder as it approaches the heights—the coldness increases, the responsibility increases.” All ugly manners and pessimism are below such leaders: “indignation is the privilege of the Chandala” (Indian untouchable). What is bad? “Everything that proceeds from weakness, from revengefulness.” [A 57]

Thus Nietzsche holds that the purpose for the lie of “faith” makes a great difference in the effect it will have on society. Do the priests lie in order to preserve (as in the book of Manu, and presumably Greek myth), or to destroy (as in Christianity)? Thus Christians and socialist Anarchists are identical in their instincts: both seek solely to destroy. The Roman civilization was a magnificent edifice for the prosperity and advancement of life, “the most magnificent form of organization under difficult circumstances which has yet been achieved”, which Christianity sought to destroy because life prospered within it. These “holy anarchists” made it a religious duty to “destroy the world”, which actually meant, “destroy the Roman Empire”. They weakened the Empire so much that even “Teutons and other louts” could conquer it. Christianity was the “vampire” of the Roman Empire. These “stealthy vermin,” shrouded in night and fog, crept up and “sucked out” from everyone “the seriousness for true things and any instinct for reality.” Christianity moved truth into “the beyond”, and “with the beyond one kills life.”

Before charging Nietzsche with possibly irresponsible invective, compare the above with Gibbon’s summary of the role of Christianity in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of a military spirit were buried in the cloister: a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers’ pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity.

On the positive side, Gibbon notes that even though Christianity clearly hastened the demise of Rome, it “mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors”. This would seem to parallel Nietzsche’s view that Christianity seeks to control the uncivilized not by teaching them the self-discipline needed to control their own impulses, but by making them too “sick” to do a great deal of harm. [A 58; Gibbon, Chapter 38 ]

“The whole labor of the Ancient World in vain!”: thus does Nietzsche overstate the magnitude of the calamity. (Our civilization’s heritage from classical antiquity is obviously far from nothing!). Nonetheless, no one who prefers civilization to barbarism can be indifferent to the point here raised. Nietzsche emphasises that the foundations for a scholarly culture, for science, medicine, philosophy, and art, had all been magnificently laid in antiquity, only to be destroyed by the advent of Christianity. Today, he says, we have certainly made great progress, but each of us still retains bad Christian habits and instincts which we must work hard to overcome. Two thousand years ago, we had acquired that clear eye for reality, patience, attention to detail, seriousness in even small matters—and it was not obtained by “drill” or from habit, but flowed naturally from a civilized instinct. All this was lost! And it was not lost to some natural disaster or destroyed by “Teutons and other buffalos” (Nietzsche’s contempt for German nationalism and militarism knew no bounds!) but it was “ruined by cunning, stealthy, invisible, anemic vampires. Not vanquished-merely drained. Hidden vengefulness, petty envy become master.” Everything that was miserable and filled with bad feelings about itself came to the top at once. [A 59]…

The meaning and significance of the Renaissance is considered in this next-to-last section of Der Antichrist. “The Germans have cheated Europe out of the last great cultural harvest which Europe could still have brought home—that of the Renaissance.” Nietzsche views the Renaissance as “the revaluation of Christian values,” that is, the repudiation of life-denying Christian values and their replacement with secular values which emphasise art, culture, learning, and so on. With the Renaissance in Italy, Christianity was being repudiated at its very seat. “Christianity no longer sat on the Papal throne! Life sat there instead!”

Nietzsche envisions the immortal roar of laughter that would have risen up from the gods on Mount Olympus had Cesare Borgia actually succeeded in his ruthless quest to become Pope. (The notorious murderer and poisoner Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, spread his power ruthlessly across Italy. Father and son appointed or poisoned Cardinals as needed to position the son for election as the next Pope. However, the plan went awry when they accidentally tasted some wine that had been “prepared” to rid themselves of a wealthy cardinal! The father died, and the son became gravely ill, and was hence in no position to coerce the selection of his father’s successor.)

Nietzsche envisions the immortal roar of laughter that would have risen up from the gods on Mount Olympus had Cesare Borgia actually succeeded in his ruthless quest to become Pope. (The notorious murderer and poisoner Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, spread his power ruthlessly across Italy. Father and son appointed or poisoned Cardinals as needed to position the son for election as the next Pope. However, the plan went awry when they accidentally tasted some wine that had been “prepared” to rid themselves of a wealthy cardinal! The father died, and the son became gravely ill, and was hence in no position to coerce the selection of his father’s successor.)

Nietzsche laments that this great world-historical event—life returning to Western culture—was ultimately undone by the work of “a German monk,” Martin Luther, who harbored the vengeful instincts of “a failed priest.” Through Luther’s Reformation, and Catholicism’s answer to it, the Counter-Reformation, Christianity was restored. [A 60] One might be tempted to dismiss Nietzsche’s dramatic interpretation of the Renaissance, except that his view meshes with that of Jacob Burckhardt, the single most influential historian of Renaissance civilization who ever lived. Burckhardt’s monumental work, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), has influenced the study of that period as much as Gibbon’s Decline and Fall did that of ancient Rome. Neitzsche and Burckhardt were colleagues at the University of Basle, and friends as well. In the first section of his Civilization, Burchkardt writes that the greatest danger ever faced by the Papacy was its secularization during the Renaissance.

The danger that came from within, from the Popes themselves and their nipoti (relativies, “nepotism”), was set aside for centuries by the German Reformation… The moral salvation of the papacy was due to its mortal enemies… Without the Reformation—if indeed it is possible to think it away—the whole ecclesiastical state would have passed into secular hands long ago.

Pope Julius II, powerfully anti-Borgia, was “the savior of the Papacy,” who put an end to the practice of the buying and selling of Church positions. However, the Counter-Reformation “annihlated the higher spiritual life of the people,” according to Burckhardt. Nietzsche would have said this was because they had become Christian once again.

The final section of Der Antichrist contains “the most terrible charge” against the Christian Church that “any prosecutor has ever uttered… I call Christianity the one great curse, the one great intrinsic depravity, the one great instinct for revenge for which no expedient is sufficiently poisonous, secret, subterranean, petty—I call it the one immortal blemish of mankind.” Nietzsche suggests that instead of calculating time from the “unlucky day” on which this “fatality” arose, time should be measured instead from its last day: “from today.” [A 62].

Needless to say, Nietzsche’s Der Antichrist did not prove to be the dagger in the heart of Christianity he hoped it would. After finishing this work (which was not actually published until 1895), Nietzsche wrote Ecce Homo, a philosophical autobiography, in which we first see signs of the self-aggrandizing delusions which were to characterize his incipient mental collapse. The final major work of 1888 was Nietzsche Contra Wagner, containing more polemics against the “decadence” and anti-Semetism of Wagner’s followers, much of which was taken from his earlier published works. Nietzsche’s philosophical writings end there, in the closing weeks of 1888. No doubt the breakdown which followed was hastened by the frantic pace of work during that period. Living in Turin, Italy, alone as was his habit, he continued to send letters to his family and friends.

Early in January, 1889, Nietzsche collapsed on the street in Turin. Some local people helped him back to his room, and he was soon alone again. On January 6 he sent letters to Burckhardt and to Franz Overbeck, another friend and colleague at the University of Basle, displaying obvious signs of insanity. Burckhardt, quite concerned, consulted Overbeck, who was soon on a train headed for Turin to assist his friend. Overbeck brought Nietzsche back to his mother in Germany. He was placed in an institution for a few months, and was then released to the care of his family, where he lived another eleven years as an invalid. Nietzsche actually died twice: his mind died in 1889, while his body lived on helplessly until 1900…

If Nietzsche’s polemically effective suggestion had been adopted—to begin counting time from the start of Christianity’s presumed demise, the writing of Der Antichrist—then I would now be writing these words in the year 100 P.C., the hundredth year of the post-Christian era. It would obviously be premature to expect such a calendar to gain widespread acceptance today! Yet the failure of Nietzsche’s impossibly high expectations should not cause us to overlook the significance of this monumental work, with its searing insights into the psychology of Christian belief. All those who wish not to renounce life but to affirm it, all who seek to proclaim a triumphant “yes” to human prosperity, knowledge, and happiness, will find in Der Antichrist invaluable insights on how those goals can be achieved—and on what stands on the way of them.

Notes:

There are two excellent English translations of Der Antichrist readily available, one by R. J. Hollingdale (Penguin Classics, 1968), the other by Walter Kaufmann (in Kaufmann’s The Portable Nietzsche, Penguin Books, 1978).