Or:

How the Woke monster originated

[Andrew] Carnegie, then, proudly surveying his Diplodocus, could feel that its bones had been provided with a fitting reliquary. He was not, though, the only foreign visitor to London that May who believed that a proper understanding of science would enable humanity to attain world peace.

One day before the unveiling of the Diplodocus, a Russian named Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov—Lenin, as he called himself—had also visited the city’s museum of natural history. No less than Carnegie, he was a proponent of putting the lessons taught by evolution to practical effect. Unlike Carnegie, however, he did not believe that human happiness was best served by giving free rein to capital. Capitalism, in Lenin’s opinion, was doomed to collapse. The workers of the world—the ‘proletariat’—were destined to inherit the earth. The abyss that yawned between ‘the handful of arrogant millionaires who wallow in filth and luxury, and the millions of working people who constantly live on the verge of pauperism’ made the triumph of communism certain.

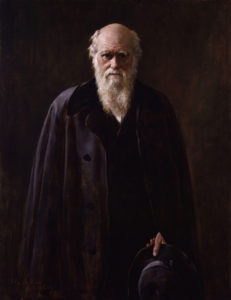

For two weeks, Lenin and thirty-seven others had been in London to debate how this coming revolution in the affairs of the world might best be expedited—but that the laws of evolution made it inevitable none of them doubted. This was why, as though to a shrine, Lenin had led his fellow delegates to the museum. It was only a single stop, however. London had a second, an even holier shrine. The surest guide to the functioning of human society, and to the parabola of its future, had been provided not by Darwin, but by a second bearded thinker who, Job-like, had suffered from bereavement and boils.

Every time Lenin came to London he would visit the great man’s grave; 1905 was no exception. The moment the congress was over, Lenin had taken the delegates up to the cemetery in the north of the city where, twenty-two years earlier, their teacher, the man who —more than any other—had inspired them to attempt the transformation of the world, lay buried. Standing before the grave, the thirty-eight disciples paid their respects to Karl Marx. There had been only a dozen people at his funeral in 1883.

That is: the year following the deaths of Darwin and Gobineau, who, had it not been for the fact that Christian ethics still reigned in the minds of agnostic scientists, their influence would have begun to lay the foundations for the revaluation of values.

None, though, had ever had any doubts as to his epochal significance. One of the mourners, speaking over the open grave, had made sure to spell it out. ‘Just as Darwin discovered the law of evolution as it applies to organic matter, so Marx discovered the law of evolution as it applies to human history’…

Marx, the grandson of a rabbi and the son of a Lutheran convert, dismissed both Judaism and Christianity as ‘stages in the development of the human mind—different snake skins cast off by history, and man as the snake who cast them off’. An exile from the Rhineland, expelled from a succession of European capitals for mocking the religiosity of Friedrich Wilhelm IV, he had arrived in London with personal experience of the uses to which religion might be put by autocrats. Far from amplifying the voices of the suffering, it was a tool of oppression, employed to stifle and muzzle protest…

‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.’ Here was a slogan with the clarity of a scientific formula.

Except, of course, that it was no such thing. Its line of descent was evident to anyone familiar with the Acts of the Apostles. ‘Selling their possessions and goods, they gave to everyone as he had need.’ Repeatedly throughout Christian history, the communism practised by the earliest Church had served radicals as their inspiration. Marx, when he dismissed questions of morality and justice as epiphenomena, was concealing the true germ of his revolt against capitalism behind jargon. A beard, he had once joked, was something ‘without which no prophet can succeed’…

Marx’s interpretation of the world appeared fuelled by certainties that had no obvious source in his model of economics. They rose instead from profounder depths. Again and again, the magma flow of his indignation would force itself through the crust of his scientific-sounding prose. For a self-professed materialist, he was oddly prone to seeing the world as the Church Fathers had once done: as a battleground between cosmic forces of good and evil… The very words used by Marx to construct his model of class struggle—‘exploitation’, ‘enslavement’, ‘avarice’—owed less to the chill formulations of economists than to something far older: the claims to divine inspiration of the biblical prophets. If, as he insisted, he offered his followers a liberation from Christianity, then it was one that seemed eerily like a recalibration of it.

Lenin and his fellow delegates, meeting in London that spring of 1905, would have been contemptuous of any such notion, of course. Religion— opium of the people that it was—would need, if the victory of the proletariat were properly to be secured, to be eradicated utterly. Oppression in all its forms had to be eliminated. The ends justified the means. Lenin’s commitment to this principle was absolute. Already, the single-mindedness with which he insisted on it had precipitated schism in the ranks of Marx’s followers. The congress held in London had been exclusively for those of them who defined themselves as Bolsheviks: the ‘Majority’.

Communists who insisted, in opposition to Lenin, on working alongside liberals, on confessing qualms about violence, on worrying that Lenin’s ambitions for a tightly organised, strictly disciplined party threatened dictatorship, were not truly communists at all—just a sect. Sternly, like the Donatists, the Bolsheviks dismissed any suggestion of compromising with the world as it was. Eagerly, like the Taborites, they yearned to see the apocalypse arrive, to see paradise established on earth. Fiercely, like the Diggers, they dreamed of an order in which land once held by aristocrats and kings would become the property of the people, a common treasury. Lenin, who was reported to admire both the Anabaptists of Münster and Oliver Cromwell, was not entirely contemptuous of the past. Proofs of what was to come were plentiful there. History, like an arrow, was proceeding on its implacable course. Capitalism was destined to collapse, and the paradise lost by humanity at the beginning of time to be restored. Those who doubted it had only to read the teachings and prophecies of their great teacher to be reassured.

The hour of salvation lay at hand. [pages 454-458]

What infected the world after the misnamed Age of Enlightenment was not the raciology of Darwin and Gobineau. Rather, millions of whites took as their new Messiah a bearded German-Jewish man whose father had been a Lutheran.

Furthermore, Darwin expected blacks to become extinct as white peoples took over their territories. It never occurred to him that Christian ethics would metastasise to such delusional levels that, in our century, it is whites who may become extinct.