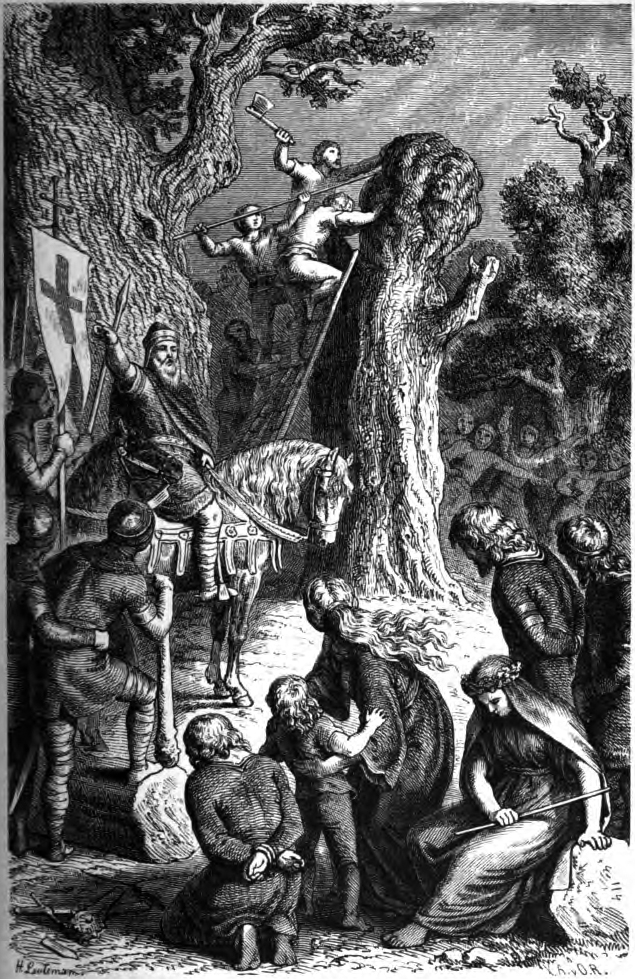

The Christian banners enter Saxony

Charles’ armies—which in the larger campaigns consisted of just 3,000 horsemen and between 6,000 and 10,000-foot soldiers—sometimes numbered more than 5,000 or 6,000 warriors. Unlike in the time of his grandfather Charles Martell, the core of the army was made up of heavy cavalry. The horsemen were armed with chain mail, helmet, shield and shin guards, with lance and battle-axe (worth approximately 18 to 20 oxen). And all this for Jesus Christ. The foot companies, still numerous, fought with mace and bow. (Only from 866, under Charles the Bald, was every Frank who owned a horse obliged to military service so that the infantry ceased to play an important role in the army.) Moreover, in the Carolingian wars, no soldiers were paid: the spoils of plunder were shared out.

The Christian butchery (‘mission by the sword’), with which Charles continued his father’s Saxon wars, began in 772. The ‘gentle king’, as he is repeatedly called in contemporary royal annals, then conquered the frontier fortress of Eresburg (today’s Obermarsberg, next to the Diemel), an important starting point of his military operations during the first half of the Saxon wars. And he destroyed (probably there) the Irminsul, the Saxon national shrine, consisting of an extraordinarily large tree trunk, which the Saxons venerated as ‘the pillar supporting the Universe’ in a sacred grove in the open air. Later Charles entrusted Abbot Sturmi of Fulda with the command of the fortress of Eresburg, which had been recaptured, again and again, lost, destroyed and rebuilt.

But other bishops and abbots also provided Charles with military services. Like the counts, they were also obliged to maintain a camp, an obligation which was also incumbent on the abbesses. Even at that time, clerical troops accompanied the Frankish army, so that, according to Sturmi’s biographer, ‘through sacred instruction in the faith, they might subject the people, bound from the beginning of the world with the chains of demons to the gentle and light yoke of Christ’. Exactly from that year onwards, Charles used a seal with the inscription: ‘Christ protects Charles, King of the Franks’.

After the Christians had completely plundered the place of worship, set fire to the sacred grove and destroyed the pillar, they left with the sacred offerings piled up there and with abundant treasures of gold and silver, ‘the gentle King Charles took the gold and silver he found there’, as the Royal Annals succinctly state. And soon after, on top of the plundered and destroyed gentile sanctuary, a church was built ‘under the patronage of Peter’ (Karpf), the gatekeeper of heaven, displacing the Saxon god Irmin (probably identical to the Germanic god Saxnoth / Tiwas). What progress!

Heinrich Leutemann’s Destruction of

the Irmin Column by Charlemagne

In the following years, ‘the gentle king’ fought mainly in Italy. Through the emissary Peter (that was the name of the envoy), Pope Adrian had invited him ‘for the love of God and in favour of the right of St Peter and the Church to help him against King Desiderius’ (Annales Regni Francorum). But already in 774, barely back from the plunder of the Longobard kingdom, the good King Charles sent four army corps against the Saxons: three of them ‘were victorious with the help of God’, as the royal analyst once again reports, while the contingent corps returned without even having fought, but ‘with great booty and without loss’ to the sweet home.

And then Charles himself somehow introduced ‘Christian banners into Saxony’ (Groszmann), with the result that ‘the war became more and more the war of faith’, as Canon Adolf Bertram acknowledged in 1899.

Concerned about the further course of the war, Charles had consulted an expert by courier if there was any sign that Mars had accelerated his career and had already reached the constellation Cancer. He conquered Sigibur on the Ruhr and crossed the Weser, ‘many of the Saxons being slain there’, advancing towards Ostfalia, intending ‘not to give up until the defeated Saxons had either submitted to the Christian religion or had been completely exterminated’. It was the programme of a thirty-three-year war ‘with an increasingly religious motivation’ (Haendier). Indeed, in its planning, it represented something new in the history of the Church, ‘a direct missionary war, which is not a preparation for missionary work but is itself a missionary instrument’ (H.D. Kahl).

This was precisely the decade in which the prayer of a sacramentary (a missal) openly called the Franks the chosen people. Charles’ wars against the Saxons were already regarded as wars against the heathen and were therefore considered just. ‘Rise, thou chosen man of God, and defend the Bride of God, the Bride of thy Lord’, the Anglo-Saxon Alcuin, one of his closest advisors, urged him. And later the monk Widukind of Corbey wrote: ‘And when he saw how his noble neighbouring people, the Saxons, were imprisoned in vain heresy, he strove by all means to lead them to the true way of salvation’.

By all means. As far as the year 765 is concerned, the royal Annals make it lapidary clear: ‘After having taken hostages, seizing abundant booty and three times provoking a bloodbath among the Saxons, the aforementioned King Charles returned to France with the help of God (auxiliante Domino)’.

Booty, bloodbaths and God’s help are things that keep coming back, and the good God is always on the side of the strongest. In 776, ‘God’s strength justly overcame theirs… and the whole multitude of them, who in panic had fled one after another, killing one another… succumbed to the mutual blows, and so were surprised by God’s punishment. And how great was the power of God for the salvation of the Christians no one can say’. In 778, ‘A battle began there, which had a very good end. With God’s help the Franks were victorious and a great multitude of Saxons were slaughtered’. In 779, ‘with the help of God’, etc. And between the regular mass murders in the summers, sometimes in this palace estate and sometimes in that city, the so-called peaceful king celebrated Christmas…

The heathen were being fought, and that justified everything. Groups of clergymen accompanied the beheader. Miracles of all kinds took place. And after each campaign, they returned with abundant booty. In the principality of Lippe, there were mass baptisms, especially of nobles: the Saxons came with women and children in countless numbers (inumerabilis multitudo) and had themselves baptised and left as many hostages as the king demanded.

And at the brilliant national assembly, held at Paderborn in 777 they again thronged and solemnly abjured ‘Donar, Wotan and Saxnot and all evil spirits: their companions’ and pledged faith and allegiance ‘to God the Father almighty, to Christ the Son of God and the Holy Spirit’.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: Can you see why WDH is the only worthwhile site among our forums? So-called anti-Semitic racialists are unable to see that overthrowing the Aryan Gods and putting the Jewish god in their place is the ultimate treason!

2 replies on “Christianity’s Criminal History, 164”

Nicht in kalten Marmorsteinen,

Nicht in Tempeln, dumpf und tot:

In den frischen Eichenhainen

Webt und rauscht der deutsche Gott.

Not in cold marble stones,

Not in temples dull and dead:

In the fresh oak groves

Weaves and rustles the German God.

Are there any Whites left in in the West, however? The demographic numbers give around 70% per American state – and that’s counting untold myriads of frail boomers. The cute Irish YouTuber WhatIfAltHist opines that a civil war would be won by some deranged Christcuck mutts.