The article published yesterday on The Occidental Observer, ‘The Holocaust of Six Million Jews—in World War I’ by Thomas Dalton—yes: the First (!) World War—is worth reading.

If we now ask ourselves what influence, apart from that of Wagner’s music and the less immediate but still living influence of the Swastika, could have helped the young Adolf to acquire so early the power to transcend space and time in this way, we are immediately led to think of his only childhood love:  the beautiful Stephanie, with her heavy blond braids wrapped around her head like a soft, shiny crown[1]; Stephanie to whom he never dared to speak because he had ‘not been introduced to her’ [2] but who had become in his eyes ‘the female counterpart of his own person’.[3]

the beautiful Stephanie, with her heavy blond braids wrapped around her head like a soft, shiny crown[1]; Stephanie to whom he never dared to speak because he had ‘not been introduced to her’ [2] but who had become in his eyes ‘the female counterpart of his own person’.[3]

August Kubizek insists on the exclusivity of this very special love: the ‘ideal’ plane on which he always remained. He tells us that the young Adolf, who identified Stephanie with the Elsa of Lohengrin and ‘other heroine figures of the Wagnerian repertoire’[4] didn’t feel the slightest need to talk or hear her, as he was sure that ‘intuition was enough for the mutual understanding of people out of the ordinary’. He was satisfied to watch her pass by from afar; to love her from afar as a vision from another world.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Is the image I chose for the front cover of The Fair Race finally understood (a girl I met decades ago, and who I talk about in my last book)?

______ 卐 ______

Once, however, on a beautiful Sunday in June, something unforgettable happened. He saw her, as always, at his mother’s side, in a parade of flower floats. She was holding a bouquet of poppies, cornflowers and daisies: the same flowers under which her float disappeared. She was approaching. He had never looked at her so closely, and she had never seemed more beautiful. He was, says Kubizek, ‘delighted with the earth’. [5]

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: From the pen of Spanish Romanticist poet Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer (1836-1870):

Hoy la tierra y los cielos me sonríen,

Hoy llega al fondo de mi alma el sol,

Hoy la he visto…, la he visto y me ha mirado,

¡Hoy creo en Dios!

Terry Rooney’s translation:

Today heaven and earth smile upon me

Today the sun reaches the depths of my soul

Today I saw her… I saw her and she looked at me,

Today I believe in God!

______ 卐 ______

Then the girl’s bright eyes rested on him for a moment. She smiled carelessly at him in the festive atmosphere of that sunny Sunday, took a flower from her bouquet and tossed it to him.[6] And the witness to this scene adds that ‘never again’—not even when he saw him again in 1940, in the aftermath of the French campaign, at the height of his glory—did he see Adolf Hitler ‘happier’.

But even then, the future Führer did nothing to get closer to Stephanie. His Platonic love remained like that, ‘weeks, months, years’. Not only did he no longer expect anything from the girl after the gesture I have just recalled, but ‘any initiative she might have taken beyond the rigid framework of convention would have destroyed the image he had of her in his heart’.[7]

When one remembers what role the ‘Lady of his thoughts’ played in the life and spiritual development of the medieval knight—who could also be, though not necessarily, a figure we just caught a glimpse of, even some distant princess, whose beauty and virtues the devoted knight knew only by hearsay—and when we know, moreover, what deep links existed between the Orders of Chivalry and hermetic teaching, that is to say initiatory—one cannot help but connect the dots.

August Kubizek assures us that, at least during the years he lived in Vienna with him, the future Führer didn’t once respond to the solicitations of women, didn’t associate with any of them, didn’t approach any of them although he was ‘bodily and sexually quite normal’.[8] And he tells us that the beloved image of the woman who, in his eyes, ‘embodied the ideal German woman’ would have supported him in this deliberate refusal of any carnal adventure.

It is instructive to note the reason for this refusal, which Kubizek reports in all simplicity misunderstanding the implications of his childhood friend’s words. Adolf Hitler wanted, he tells us, to keep within himself, ‘pure and undiminished’ [9] what he called ‘the flame of Life’, in other words, the vital force. ‘A single moment of inattention, and this sacred flame is extinguished for ever’—at least for a long time—he wrote, showing us the value the future Führer attached to it. He tries, unsuccessfully, to elucidate what it is. He sees in it only the symbol of the ‘holy love’ that awakens between people who have kept themselves pure in body and spirit, and who ‘is worthy of a union destined to give the people a healthy offspring.’ [10] The preservation of this ‘flame’ was to be, he wrote, ‘the most important task’[11] of that ‘ideal state’ which the future founder of the Third German Reich thought of in his lonely hours.

This is undoubtedly true. But there is more to it than that.

__________

[1] The name Stephanie evokes the idea of a crown (Stephanos, in Greek).

[2] Kubizek, p. 88.

[3] Ibid. (‘die weibliche Entsprechung der eigenen Person’).

[4] Ibid., page 78.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., page 84.

[7] Ibid., page 87.

[8] Ibid., page 276.

[9] page 280.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

George Orwell said: ‘At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed all right-thinking people will accept without question… Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals’.

But these days, after years of hard work, Kevin MacDonald is getting a fair hearing on Jewish influence in the West—in an Israeli journal! (see KMD’s ‘My paper on Jewish influence blows up’). Despite the tearing of clothes by the usual suspects (ADL, etc.), his ideas are finally being discussed in a mainstream journal, giving him a chance to respond.

I wonder how long it will take a similar courtesy that these Israelis are extending to KMD, but this time from racialists regarding The West’s Darkest Hour?

This is our challenge to the prevailing orthodoxy in white nationalism: unlike your monocausalism, we believe that Christian ethics enabled the Jewish problem. But to this day, our unfashionable opinion has never been given a fair hearing in your highbrow forums (for example, KMD rejected Ferdinand Bardamu’s article on Christianity that now appears in The Fair Race). You haven’t done so even though it would be relatively easy to review, say, our masthead book (I only authored the preface).

This is our challenge to the prevailing orthodoxy in white nationalism: unlike your monocausalism, we believe that Christian ethics enabled the Jewish problem. But to this day, our unfashionable opinion has never been given a fair hearing in your highbrow forums (for example, KMD rejected Ferdinand Bardamu’s article on Christianity that now appears in The Fair Race). You haven’t done so even though it would be relatively easy to review, say, our masthead book (I only authored the preface).

On IQ studies

It’s true what Jared Taylor and his group say about IQ differences between races. But I have long been thinking that these studies are biased towards certain intellectual abilities, which aren’t necessarily the most important. As I wrote in my book The Human Side of Chess, what good did it do the only Americans to achieve the world championship crown, Morphy in the 19th century and Fischer in the 20th century, to have very high IQs if in their personal lives they literally lost their minds?

The problem with IQ studies is that they measure a part of intelligence, but not all of it. Those who have read the neurologist Oliver Sacks will know that, for a long time, neurology studied the left hemisphere of the brain to the detriment of the right hemisphere: something that Sacks tried to correct in his books.

Something very similar could be said of IQ studies. It isn’t credible that Asians are about five points higher than Aryans while the latter are much more creative, and Asians merely imitate what whites have come up with. It is obvious that something huge is missing in the IQ studies.

I think it is precisely judgement, so well studied by Sacks in his field of neurology and by us in psychohistory, that is missing from the ‘hemiplegic’ approach, so to speak, in IQ studies.

As I see it, if we take judgement in conjunction with the values measured by conventional IQ tests, pre-Christian Aryans would rank above not only Asians, but Jews themselves. It was Christianity that literally drove us mad. In Spanish we say ‘perdimos el juicio’, literally ‘we lost our judgement’ (we lost our minds in a non-literal translation). That’s why when we finish our translation of Savitri’s book we will continue with the translation of Deschner’s history of criminal Christianity.

An illustration of why IQ studies are so limited can be found in yesterday’s American Renaissance article by Roger Devlin, ‘How and why men and women differ in intelligence’. I’ve been a fan of Devlin’s articles debunking feminism, and even included his seminal piece on the subject in On Beth’s Cute Tits. But like everyone at AmRen, Devlin is a typical American conservative who falls into the traps conservatives fall into.

In his most recent article, for example, in which he discusses the IQ difference between men and women, Devlin is quick to add that women, especially as teenagers (men take longer to develop their faculties), outperform us linguistically and in other faculties. Such an approach to intelligence betrays the same failings in approaching intelligence compared to, say, Asians: the most important thing, judgement and creativity, is omitted.

(Conservative speaker Roger Devlin at the latest AmRen conference.) An American racialist who is not a conservative, say Andrew Anglin, is able to see the naked truth about judgement in the most brutal way possible. For example, in a text I also picked up in On Beth’s Cute Tits, Anglin tells us: ‘What I am “claiming”—which is in fact simply explaining an objective reality, based on accepted science—is that women have no concept of “race”, as it is too abstract for their simple brains. What they have a concept of is getting impregnated by the dominant male’ (from ‘White Sharia: Why we don’t have any choice’, The Daily Stormer, May 16, 2017).

(Conservative speaker Roger Devlin at the latest AmRen conference.) An American racialist who is not a conservative, say Andrew Anglin, is able to see the naked truth about judgement in the most brutal way possible. For example, in a text I also picked up in On Beth’s Cute Tits, Anglin tells us: ‘What I am “claiming”—which is in fact simply explaining an objective reality, based on accepted science—is that women have no concept of “race”, as it is too abstract for their simple brains. What they have a concept of is getting impregnated by the dominant male’ (from ‘White Sharia: Why we don’t have any choice’, The Daily Stormer, May 16, 2017).

A typical conservative would never talk like that since bourgeois codes of conduct, especially if he speaks in public, oblige him to be nice to everyone present, ladies included, and not to say brutal things.

But Anglin has better judgement than Devlin. The problem with judgement, which is part of intelligence, is that it cannot be measured by simple tests. Even in neurology Sacks had to resort to narrative, that is, to telling little biographical vignettes of those who had suffered a lesion in an area of the right hemisphere of their brains to show how it affected their judgement. The same could be said of those who have healthy brains (hardware) but who have terrible damage to their way of seeing the world (software), such as Christian ethics. In the latter case—software—, narrative is also crucial although, unlike biographical profiles, we are talking about a vast historical study of Christianity and how it metamorphosed into runaway egalitarianism (cf. Ferdinand Bardamu’s essay, now in four languages).

In sum, IQ studies are very limited. They only measure part of intelligence. If whites could get the monkey of Christianity off their backs, they would be the most intelligent subspecies of Homo sapiens on the planet.

It is curious, to say the least, that this extraordinary episode—which, apart from its own ‘resonance’ of truth, is guaranteed by Kubizek’s ignorance of the superhuman realm—has not, to my knowledge, been commented on by any of those who have tried to link National Socialism to ‘occult’ sources. Even the authors who have—quite wrongly!—wanted to attribute to the Führer a nature of ‘medium’ have not, as far as I know, attempted to use it. Instead, they have insisted on the immense power of suggestion which he exercised not only over crowds (and women), but on all those who came, even if only occasionally, into contact with him; on men as coldly detached as a Himmler; on soldiers as realistic as an Otto Skorzeny, a Hans-Ulrich Rudel or a Degrelle.

Now, it is ignorance of the first elements of the science of para-psychic phenomena to consider as ‘medium’ one who enjoys such power. A medium is the one who receives, who undergoes suggestion; not the one who is capable of inflicting it on others, and especially many others. This power is the privilege of the hypnotist or magnetizer, and in this case of a magnetizer of a stature that borders on the superhuman; of a magnetizer capable for his benefit—or rather for the idea, of which he wants to be the promoter—to play the role of a ‘medium’ to the strongest, the stalest, the most resistant to any affecting.

One is not both a magnetiser and a medium. We are one or the other, or neither. And if we want to include some ‘para-psychic’ in the history of Adolf Hitler’s political career—as I believe we are entitled to do—then the magnetizer is him, whose power of exalting and transforming human beings, by the mere spoken word, is comparable to that which Orpheus exerted, it is said, by the enchantment of his lyre, on people and beasts. The ‘medium’ is the German people, almost all of them—and some non-Germans throughout the world, to whom the radio transmitted the bewitching Voice.

The episode mentioned above, of which I have translated Augustus Kubizek’s account, [1] could very well serve as an argument in favour of the presence of ‘medium gifts’ in the young Adolf Hitler if these so-called gifts weren’t contradicted resoundingly, precisely by the astonishing power of suggestion which he didn’t cease to exercise throughout his career on the multitudes and practically all the people. Indeed, Kubizek tells us that he had the distinct impression that ‘another I’ had spoken through his friend; that the stream of prophetic eloquence had seemed to flow from him as from a force alien to him. Now, if the adolescent speaker had nothing of the ‘medium’ about him; if he was in no way possessed by ‘an Other’—god or the devil, whatever; in any case not himself—what then was this ‘other I’ who seemed to take his place during that unforgettable hour on the summit of the Freienberg, under the stars, and to substitute him so completely that the friend would have had some difficulty in recognising him, hadn’t he continued to see him?

Understandably, Auguste Kubizek didn’t ‘dare to pass judgment’ on this. However, he speaks of an ‘ecstatic state’, of ‘complete rapture’ (völlige Entrückung) and the transposition of the visionary’s experience onto ‘another plane, tailored to him’ (auf eine andere, ihm gemässe Ebene). Moreover, this recent living experience—the impression made on him by the story of the 14th-century Roman tribune translated and interpreted by Wagner’s music—had been, the witness tells us, only the ‘external impulse’ which had led him to the vision of the personal as well as the national future; in other words, which had served as the occasion for the adolescent’s access to a new consciousness: a consciousness in which space and time, and the individual state that is linked to these limitations, are transcended.

This would mean that the ‘other plane to the measure’ of the young Adolf Hitler was nothing less than that of the ‘eternal present’ and that, far from having been ‘possessed’ by an alien entity, the future master of the multitudes had become master of the Centre of his being; that he had, under the mysterious influence of his initiator—Wagner—taken the great decisive step on the path of esoteric knowledge, undergone the first irreversible mutation—the opening of the ‘third eye’ which had made him an ‘Edenic man’.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: Are you finally beginning to understand the metaphor that I have used so many times on this site (the symbol of the three-eyed raven)?

______ 卐 ______

He had just acquired the degree of being corresponding to what is called, in initiatory language, the Little Mysteries. And the ‘other I’ which had spoken through his mouth of things that his daily conscious self was still unaware of, or perhaps only half-perceived ‘as if through a veil’, a few hours before, was his true ‘I’ and that of all the living: the Being, with whom he had just realized his identification.

It may seem strange to the vast majority of my readers—including those who still venerate him as ‘our Führer forever’—that he could, at such an astonishingly young age, have shown such an awakening to supra-sensible realities. Among the men who aspire with all their ardour to essential knowledge, how many are there, in fact, who grow old in meditation and pious exercises without yet reaching this level? But if there is one area where the most fundamental inequality and the most blatant appearance of ‘arbitrariness’ reigns, it is this.

God places his august sign on the forehead of whoever pleases him;

He has forsaken the eagle, and chosen the birdie,

Said the monk. Why did he do this? Who shall tell? Nobody![2]

There is no impossibility for an exceptional adolescent to cross the barrier opened to the mind in search of principled truth, initiation into the Little Mysteries. According to what is still told in India about his life, the great Sankaracharya was one of these. And twenty-two centuries earlier, Akhnaton, king of Egypt, was also sixteen years old when he began to preach the cult of Aten, Essence of the Sun, of which the ‘Disc’ is only the visible symbol. And everything leads us to believe that there were others, less and less rare as we go back for the cycle in which we live the last centuries.

If, on the other hand, one sees in Adolf Hitler one of the figures—and undoubtedly the penultimate one—of the One who returns when all seems lost; the most recent of the many precursors of the supreme divine incarnation or of the last messenger of the Eternal (the Mahdi of the Mahometans; the Christ returned in glory of the Christians; the Maitreya of the Buddhists; the Saoshyant of the Mazdeans; the Kalki of the Hindus) or by whatever name one wishes to call him, who is to end this cycle and usher in the Golden Age of the next, then all becomes clear.

If, on the other hand, one sees in Adolf Hitler one of the figures—and undoubtedly the penultimate one—of the One who returns when all seems lost; the most recent of the many precursors of the supreme divine incarnation or of the last messenger of the Eternal (the Mahdi of the Mahometans; the Christ returned in glory of the Christians; the Maitreya of the Buddhists; the Saoshyant of the Mazdeans; the Kalki of the Hindus) or by whatever name one wishes to call him, who is to end this cycle and usher in the Golden Age of the next, then all becomes clear.

For then, naturally, he was an adolescent and before that, already an exceptional child: a child whose sign, a word, a nothing (or what might seem ‘a nothing’ to anyone else) was enough to awaken his intellectual intuition. So, it is not impossible to think that, from the school years 1896-97, 1897-98 (and partly 1898-99), which he spent as a pupil at the Benedictine abbey of Lambach-an-Traun, in Upper Austria, the magic of the Holy Swastika—a powerful cosmic symbol, an immemorial evocator of the principal truth—seized him, penetrated him, dominated him; that he had, beyond the exhilarating solemnity of Catholic worship, identified with it forever.

For the Reverend Father Theodorich Hagen, Abbot of Lambach, had, thirty years earlier, this sacred sign engraved on the walls, on the woodwork, in every corner of the monastery, however paradoxical such an action may seem ‘without counterpart in a Christian convent’.[3] And as he sang in the choir the young Adolf, nine years old in 1898, ten years old in 1899, had ‘right in front of him’ on ‘the high back of the abbot’s chair’, in the very centre of Father Hagen’s heraldic shield, the ancient Symbol now destined to remain forever attached to his name.

It is natural, then, that he should have been aware very early on, in parallel with his opening up to the world of Essences, of what had to be done in this visible and tangible world, at the eleventh hour, a ‘recovery’; or even only to suggest one—to sound the last, supreme warning of the Gods, in case the universal decadence was irredeemable (as indeed it seems to be). And, as Kubizek reports, there is every reason to believe that this was the case, since even at the time of his extraordinary awakening the future Führer spoke of the ‘mission’ (Auftrag) he was to receive one day, to lead the people ‘from bondage to the heights of freedom’.[4]

__________

[1] There is a French edition of Auguste Kubizek’s book Adolf Hitler, mein Jugendfreund, published by Gallimard. Unfortunately, the original text has been shortened. The most interesting passages of this story are not included in the translation.

[2] Leconte de Lisle in the poem entitled ‘Hieronymus’, in Poèmes tragiques.

[3] Brissaud : Hitler et l’Ordre Noir, page 23.

[4] Kubizek: Adolf Hitler, mein Jugendfreund, page 140.

Spotlight

or

Antichristianity for beginners

These days I’ve really gotten into the movie Spotlight filmed in 2015, winner of the Oscar for Best Picture, and directed by Thomas McCarthy. The film tells a real-life story: how the investigative unit of The Boston Globe newspaper, called ‘Spotlight’, brought to public light a scandal in which the highest authorities of the Catholic Church concealed a huge amount of sexual abuse perpetrated by different priests (no: McCarthy is not a Jew).

These days I’ve really gotten into the movie Spotlight filmed in 2015, winner of the Oscar for Best Picture, and directed by Thomas McCarthy. The film tells a real-life story: how the investigative unit of The Boston Globe newspaper, called ‘Spotlight’, brought to public light a scandal in which the highest authorities of the Catholic Church concealed a huge amount of sexual abuse perpetrated by different priests (no: McCarthy is not a Jew).

Artistically, the film is a true marvel. Furthermore, inside the window of discourse, or Overton window, it represents the first baby step in crossing the psychological Rubicon. (Remember that on this site we blame the artificial Jews—the Christians—more than the common Jews since the traitor is worse than the subversive of an alien group.)

If we have a loved one who is a normie, I can think of nothing better than giving him a movie that won the top Oscar to see if he can take his first step across the river. Even to my 2013 list of the ten films I most recommend, I would add an eleventh: Spotlight. (If I were asked why I included Disney’s Sleeping Beauty on that list my answer is that, although it is for children, it gives its due to the enormous beauty of the Aryan woman; Tchaikovsky’s music is extraordinarily well handled, and Eyvind Earle’s drawings are superb.)

Of my list of 50 films I suggested for entertainment in the early months of the Covid quarantine, I can hardly watch most of them. The situation in the West depresses me so much that I can only think of my priesthood of the sacred words.

But Spotlight is the exception! I can still watch it, and even the YouTube interviews with the actors and real-life reporters from The Boston Globe for the simple fact that it represents the first step that a normie can take, a move toward my side of the river.

The majority of Hitler’s monologues, which are published in this volume, were handed down by Heinrich Heim (pic above). He was born in Munich on 15 June 1900, and grew up in Zweibrücken where he also attended school.

In keeping with his heritage—Heim came from an old and respected Bavarian legal family (his father was a judge at the Bavarian Supreme Court and from 1918 to 1925 a member of the Bavarian State Court and for a time of the Disciplinary Court)—he studied law at the University of Munich.

Heim met Rudolf Hess at an economics college and through him came into contact with the NSDAP, which he joined as early as 19 July 1920. After passing his exams for the higher judicial and administrative service, the young lawyer set up his own practice in Munich. He worked in an office partnership with Dr Hans Frank, who was already Hitler’s and the NSDAP’s preferred legal representative at that time. Heim, too, immediately became active as a lawyer for the party. He primarily represented the interests of the NSDAP’s relief fund, which was headed by Martin Bormann. This established a collaboration that lasted until 1945.

When Rudolf Hess was appointed Deputy Leader in 1933 and Martin Bormann appointed as his chief of staff, the systematic development of an efficient party headquarters began.

Bormann brought Heim onto his staff on 13 August 1933 where he worked, albeit initially on a fee basis without clearly defined responsibilities. Only after the National Socialist party leadership had been given a say in state legislation and namely in the appointment and promotion of civil servants, other lawyers and staff were recruited. In the newly established constitutional law department of the party headquarters, Heim was assigned the handling of all questions concerning the judiciary. He remained in this position of head of the Reich Office until the end of 1939. In 1936 he was appointed senior government councillor, and in 1939 he received the rank of ministerial councillor.

When, at the beginning of the war, Martin Bormann (who had already been in Berlin from time to time and had kept the connection between Hitler and the party leadership) followed the leader of the NSDAP to his respective headquarters, he took Heim with him as his adjutant. He remained in this position from the end of 1939 until the autumn of 1942. After that, when he returned to the Braune Haus in Munich, he headed a newly created department until the end of the war, in which fundamental questions of a reorganisation of Europe were dealt with.

The decisive factor for Heim’s command to the Führer’s headquarters was Hitler’s wish. If possible, he only wanted to see people he knew in his environment.

The fact that Heim was one of his earliest followers (he had the old membership number 1782) also established a special relationship of trust that made him seem suitable to record Hitler’s discussions and explanations. As Bormann’s adjutant, Heim not only ate regularly at Hitler’s table, but he was also frequently invited to the nightly teatimes in the Führer’s bunker, which were attended only by the closest political confidants and the secretaries. The circle was rarely larger than six to eight people. The records of these nocturnal monologues by Hitler make up the special value of Heim’s collection.

In spring 1942, Heim was commissioned to assist the painter Karl Leipold, to whom he was particularly close, in preparing an exhibition at the Haus der Kunst. For the time of his absence from the Führer’s headquarters from March to July 1942, Bormann was looking for a substitute. Since no one was available in the party chancellery, he turned to the Gauleiter of the NSDAP and asked them for suggestions. Among the names he was given was that of Dr Henry Picker, a senior government official. He had been proposed by the Gauleiter of Oldenburg, Karl Rover. The party chancellery made a preliminary selection, and the decision lay with Hitler himself.

Bormann accepted Picker as Heim’s representative because the proposal came from a proven Gauleiter and Hitler transferred the recognition he paid to Picker’s father to his son. Senator Daniel Picker had already promoted the NSDAP in Wilhelmshaven in 1929 and brought its leader into contact with representatives of the shipyard industry and the navy.[1]

During his visits to the port city, Hitler had repeatedly been a guest in the Picker house. For the sake of clarification, it deserves to be stated that Henry Picker did not come to the Führer’s headquarters as a civil servant or lawyer, but served there as Bormann’s adjutant on behalf of the Party Chancellery. His permanent duties therefore included recording Hitler’s conversations during the official lunch and dinner table.

____________

[1] Picker: Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier (op. cit.), page 12.

Jung-inspired term

In some grey letters in my previous entry, I spoke of the ‘language of the Self’ without defining it. Here is an approximation:

Hölderlin, Kleist, and Nietzsche are obviously alike even in respect of the outward circumstances of their lives; they stand under the same horoscopical aspect. One and all they were hunted by an overwhelming, a so-to-say superhuman power, were hunted out of the warmth and cosiness of ordinary experience into a cyclone of devastating passion, to perish prematurely amid storms of mental disorder, and one of them by suicide.

A power greater than theirs was working within them, so that they felt themselves rushing aimlessly through the void. In their rare moments of full awareness of self, they knew that their actions were not the outcome of their own volition but that they were thralls, were possessed (in both senses of the word) by a higher power, the daimonic.

I term ‘daimonic’ the unrest that is in us all, driving each of us out of himself into the elemental. It seems as if nature had implanted into every mind an inalienable part of the primordial chaos, and as if this part were interminably striving—with tense passion—to rejoin the superhuman, suprasensual medium whence it derives…

Source: The Struggle with the Daimon. Understanding how I use the term ‘Self’ in this sense can be done by reading Jung’s Man and His Symbols. On this site I stole a page from that book: here.

Despite the polemics that the name of the Führer still unleashes, more than a quarter of a century after the disappearance of his physical person, his initiation into a powerful esoteric group, in direct connection with the primordial Tradition, is no longer in doubt.

Certainly, his detractors—and there are many!—have tried to present him as a man driven to all kinds of excesses, having been driven by his ‘hubris’ to betray the spirit of his spiritual masters. Or they saw in him a master of error, a disciple of ‘black magicians’, himself the soul and instrument of subversion (in the metaphysical sense) at its most tragic. But their clarity is suspect only because they all take the ‘moral’ point of view—and a false morality, since it is supposedly ‘the same for all men’.

What repels them, and prevents them a priori from recognising the truth of Hitlerism, is the total absence of anthropocentrism, and the enormity of the ‘war crimes’ and ‘crimes against humanity’, to which he is historically linked. In other words, they reproach him with being at odds with ‘universal consciousness’.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: What Aryans don’t understand is that one has to reject theism and embrace pantheism to save one’s race (see my last comment in another thread).

______ 卐 ______

But the all-too-famous ‘universal conscience’ doesn’t exist; it has never existed. It is, at most, only the set of prejudices common to people of the same civilisation, insofar as they don’t feel or think for themselves, which means that it is not ‘universal’ in any way. Furthermore, spiritual development is not a matter of morality but of knowledge; of direct insight into the eternal Laws of being and non-being.

It is written in those ancient Laws of Manu, whose spirit is so close to that of the most enlightened followers of the Führer, that ‘a Brahmin possessing the entire Rig Veda’ (which doesn’t mean knowing by heart the 1009 hymns which compose it but the supreme knowledge), the initiation (which would imply the perfect understanding of the symbols hidden therein under the words and images they evoke) it is written, I say, that such a Brahman ‘would be stained with no crime, even if he had slain all the inhabitants of the three worlds, and accepted food from the vilest man’.[1]

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: This reminds me of ‘Dies irae’, the first essay in my Day of Wrath. The error of Christians and secular neochristians—virtually all whites—is that they think through New Testament value codes; not like the Star-Child.

______ 卐 ______

Certainly, such a man, having transcended all individuality, could only act dispassionately and, like the sage spoken of in the Bhagawad-Gîta, ‘in the interest of the universe’. But it doesn’t follow that his action would correspond to a ‘man-centred’ morality. There is even reason to believe that it could, if need be, deviate from this. For nothing proves that the ‘interest of the Universe’—the agreement of the action with the deep requirements of a moment of history, which the initiate grasps from the angle of the ‘eternal Present’— sometimes doesn’t require the sacrifice of millions of men, even the best.

Much has been made of Adolf Hitler’s membership (as well as that of several very influential figures of the Third Reich, including Rudolf Hess, Alfred Rosenberg, Dietrich Eckart) in the mysterious society founded in 1912 by Rudolf von Sebottendorf. Much has also been said about the decisive influence on him of readings of a very particular esoteric and messianic character, among others the writings of the former Cistercian monk Adolf Josef Lanz, known as Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, founder (in 1900) and Grand Master of the ‘Order of the New Temple’, and his journal, Ostara (founded in 1905). We did not fail to recall his close connection with the geopolitician Karl Haushofer, member of the Société du Vril, versed in the knowledge of secret doctrines, which would have been revealed to him in India, Tibet and Japan, and very aware of the immense ‘magic power’ of the Swastika.[2]

Finally, the particular role of initiator played by at least Dietrich Eckart—if not Eckart and Rudolf Hess, although both have always presented themselves in public life as his faithful disciples and collaborators—has been emphasized. Eckart is said to have declared, in December 1923, on his deathbed, before some of his brothers of the Thule Society, that the masters of the said Society, including himself, would have given Adolf Hitler ‘the means of communicating with them’, that is, with the ‘higher unknowns’ or ‘intelligences outside of humanity’, and that he, in particular, would have ‘influenced history more than any other German’.[3]

It should not be forgotten that, whatever the initiatory training he underwent later on, it seems certain that the future Führer was already ‘between the ages of twelve and fourteen’ and perhaps even earlier, in possession of the fundamental directives of his historical ‘self’; that he had already shown his love for art in general, and especially for architecture and music; that he had already shown interest in German history (and history in general); that he was an ardent patriot; that he was hostile to the Jews (whom he felt to be the absolute antithesis of the Germans); and finally, his boundless admiration for all of Richard Wagner’s work.

It seems certain, from the account of his life up to the age of nineteen given by his teenage friend August Kubizek, that his great, true ‘initiator’—the one who really awakened in him a more than a human vision of things before any affiliation with any esoteric teaching group—was Wagner, and Wagner alone. Adolf Hitler retained all his life the enthusiastic veneration he had, barely out of childhood, devoted to the Master of Bayreuth. No one has ever understood or felt the cosmic significance of Wagnerian themes as he did—no one, not even Nietzsche who had undoubtedly gone some way towards knowing the First Principles. The creation of Parsifal remained an enigma for the philosopher of the ‘superman’, who only grasped the Christian envelope. The Führer, on the other hand, knew how to rise above the apparent opposition of opposites—including that which seems to exist between the ‘Good Friday Enchantment’ and the ‘Ride of the Valkyries’. He saw further ahead.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: We’ve talked a lot about Parsifal on this site, and I’ve also read what Nietzsche says about that opera (he loved the Prelude). If we take into account what I and others have been saying about Bach’s music, we see that Parsifal was a step forward in that syncretism of the Christian with the Pagan: something that Hitler understood perfectly, although the ultimate goal was pan-Germanic Paganism stripped of Christian influence. The Wagnerian Richard Strauss, who premiered works during the Third Reich, could have continued crossing that bridge but the Allies took it upon themselves to cut off neopagan culture and impose consumer capitalism, or communism, on both sides of the Berlin Wall.

Above I mentioned my ‘Dies irae’. To understand Richard Strauss better, remember what I say there about a symphonic poem I listened to countless times in my bedroom as a teenager: Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Strauss’s opus 30.

______ 卐 ______

Behind the ‘poetic setting of Wagnerian drama’, Hitler welcomed ‘the practical teaching of the obstinate struggle for selection and renewal’[4] and in the Grail, the source of eternal life, the very symbol of ‘pure blood’. And he praised the Master for having been able to give his prophetic message both through Parsifal and the pagan form of the Tetralogy. Wagner’s music had the gift of evoking in him the vision not only of previous worlds, but of scenes of history in the making; in other words, of opening the gates of the eternal Present—and this, apparently, from adolescence, if we are to believe the admirable scene reported by Auguste Kubizek which would have taken place following a performance of Wagner’s Rienzi at the Linz Opera House, when the future Führer was sixteen. The scene is too beautiful not to take the liberty of quoting it in full.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Wagner’s opera is about the life of Cola di Rienzi, a papal notary turned political leader, who lived in medieval Italy and succeeded in overthrowing the noble classes in Rome and giving power to the people. Magnanimous at first, he had to quell a revolt by the nobles to regain their privileges. In time, popular opinion changed, and the Church, which at first was in his favour, turned against him. At the end of the opera the people burned the Capitol in which Rienzi and a few followers met their fate.

______ 卐 ______

On leaving the theatre in Linz, where they had just seen a performance of Richard Wagner’s Rienzi, the two young men, Adolf and Augustus, instead of going home took, even though it was already past midnight, ‘the path leading to the top of the Freienberg’. They liked this deserted place because they had spent many a beautiful Sunday afternoon there alone in the middle of nature.

Now it was young Adolf who, visibly upset after the show, had insisted that they return there, despite the late hour or perhaps because of it. ‘He (Adolf) walked on’, writes Augustus, ‘without saying a word, without taking my presence into account. I had never seen him so strange, so pale. The higher we climbed, the more the fog dissipated…’

I wanted to ask my friend where he wanted to go like that, but the fierce and closed expression on his face prevented me from asking him the question… When we reached the top, the fog in which the city was still immersed disappeared. Above our heads the stars were shining brightly in a perfectly clear sky. Adolf then turned to me and took both my hands and clasped them tightly between his own. It was a gesture I had never seen him do before. I could feel how moved he was. His eyes shone with animation. The words did not come out of his mouth with ease, as usual, but in a choppy way. His voice was hoarse, and betrayed his upset.

Gradually he began to speak more freely. Words poured out of his mouth. Never before had I heard him speak, and never again was I to hear him speak as he did when alone, standing under the stars, we seemed to be the only creatures on earth. It is impossible for me to relate in detail the words my friend spoke in that hour before me.

Something quite remarkable, which I had never noticed when he had previously spoken struck me then: it was as if another ‘I’ was speaking through him: an Other, in contact with whom he was himself as upset as I was. It was impossible to believe that he was a speaker who was intoxicated by his own words. Quite the contrary! I rather had the impression that he himself experienced with astonishment, I would even say with bewilderment, what was flowing out of him with the elemental violence of a force of nature.

I dare not pass judgment on this observation. But it was a state of rapture in which he transposed into a grandiose vision, on another plane, his own—without direct reference to this example and model, and not merely as a repetition of this experience—what he had just experienced in connection with Rienzi. The impression made on him by this opera had, rather, been the external impulse that had compelled him to speak. Like the mass of water, hitherto held back by a dam, rushes forward, irresistible, if the dam is broken, so the torrent of eloquence poured out of him, in sublime images, with an invincible power of suggestion, he unfolded before me his own future and that of the German people…

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: For decades I have called this phenomenon ‘the language of the Self’. (Alas, in Neanderthal land where I live, I never had a chance to use it on a mortal; only in my soliloquies.)______ 卐 ______

Then there was silence. We went back down to the city. The clocks in the church towers struck three in the morning. We parted in front of my parents’ house. Adolf shook my hand. Stunned, I saw that he was not going home but back up the hill. ‘Where do you want to go again?’, I asked him, puzzled. He answered laconically: ‘I want to be alone’. I followed him for a long time with my eyes, while he went up the empty street in the night, wrapped in his dark coat.[5]

‘And’, Kubizek adds, ‘many years were to pass before I understood what that hour under the stars, during which he had been lifted above all earthly things, had meant for my friend’. And he reports a little later on the very words that Adolf Hitler pronounced, much later, after having recounted to Frau Wagner the scene that I have just recalled, unforgettable words: ‘It was then that everything began’. That was when the future master of Germany was, I repeat, sixteen years old.

_________

[1] Laws of Manu, Book Eleven, verse 261.

[2] Brissaud: Hitler et l’Ordre Noir (op. cit.), page 53.

[3] Ibid., pages 61-62.

[4] Rauschning: Hitler m’a dit (op. cit.), page 257.

[5] Auguste Kubizek, Adolf Hitler, mein Jugendfreund, 1953 edition, pages 139-141.

Editor’s note: This site has been promoting Richard Carrier’s work about the dubious historicity of Jesus. But Carrier is a typical neochristian. As Robert Morgan once said, the Christian influence on culture has been so profound that even atheists like Dawkins and Carrier accept the Christian moral framework without question. Carrier’s liberalism has gone so far that he even subscribes the psychosis en mass that a human being can choose his or her sex, disregarding biology.

Editor’s note: This site has been promoting Richard Carrier’s work about the dubious historicity of Jesus. But Carrier is a typical neochristian. As Robert Morgan once said, the Christian influence on culture has been so profound that even atheists like Dawkins and Carrier accept the Christian moral framework without question. Carrier’s liberalism has gone so far that he even subscribes the psychosis en mass that a human being can choose his or her sex, disregarding biology.

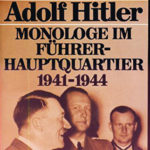

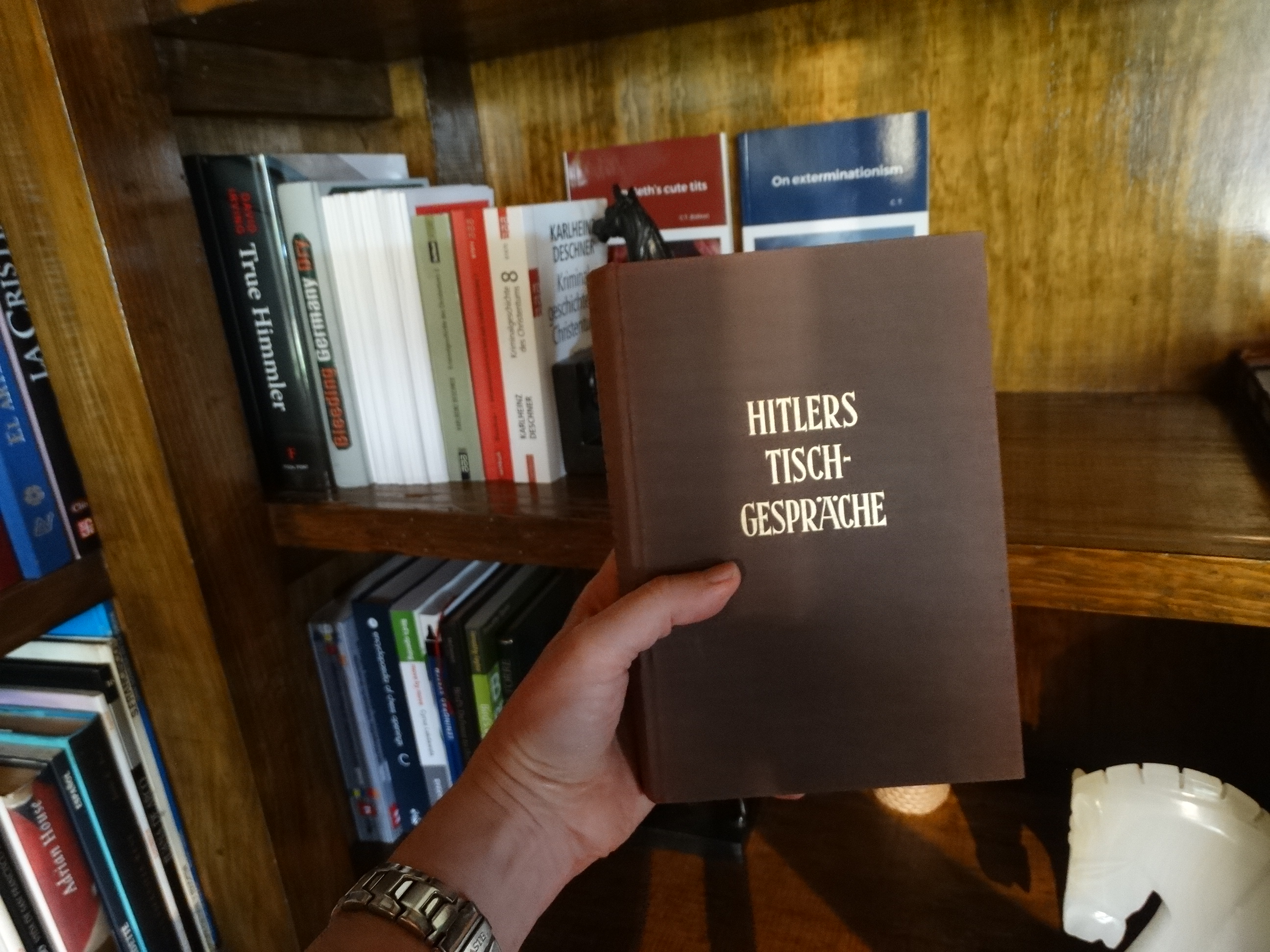

Carrier also talks nonsense about Hitler, especially about the Führer’s after-dinner talks. All his rigour as a scholar of 1st-century Mediterranean religions goes out the window when he addresses Hitler’s anti-Christianity. Carrier cheats by deliberately using sloppy English translations instead of the originals (this video featuring David Irving and Richard Weikart explains it briefly).

Here is my hand holding one of the good German editions, Henry Picker’s, which, unlike the popular translations, wasn’t slightly altered. It is time to refute Carrier’s claim that Hitler wasn’t anti-Christian, although in this new translation I will be using another edition also mentioned in the above-linked video, not the book in my hand. However, the editor’s introduction is too long for a single blog post and I’ll have to divide it into parts (i, ii, iii, etc.). If you want to read it all in the original language, you can do so in the German section of this site.

Here is my hand holding one of the good German editions, Henry Picker’s, which, unlike the popular translations, wasn’t slightly altered. It is time to refute Carrier’s claim that Hitler wasn’t anti-Christian, although in this new translation I will be using another edition also mentioned in the above-linked video, not the book in my hand. However, the editor’s introduction is too long for a single blog post and I’ll have to divide it into parts (i, ii, iii, etc.). If you want to read it all in the original language, you can do so in the German section of this site.

______ 卐 ______

Adolf Hitler

Monologues at the Führer’s Headquarters 1941-1944

– The Records of Heinrich Heim Edited by Werner Jochmann –

Introduction

Shortly after the beginning of the war against the Soviet Union, Reichsleiter Martin Bormann suggested recording Hitler’s conversations during breaks in the Führer’s headquarters. He was guided by the following considerations: After years of unprecedented restlessness with travels, visits, events, intensive consultations with architects, artists, party leaders, representatives of the state, the economy and the Wehrmacht, and after the major foreign policy actions and the first campaigns of the Second World War, the Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht was now directing operations against the Red Army with his staff from East Prussia. To preserve for posterity the ideas and conceptions he developed in this seclusion and during the most decisive phase of the war so far, Bormann, as head of the party chancellery, asked his adjutant Heinrich Heim to set them down.

On the way home from a lunch meeting with Hitler at the end of June or beginning of July 1941, Heim reports, Bormann suggested that he ‘try to write down from memory an omission we had just heard. What I submitted to the Reichsleiter seemed to him to miss what he was interested in; he therefore made a transcript himself and submitted it to me; inwardly I held fast to my idea, even if I could not reprove his’. Some of the difficulties that had been encountered in this accidental recording of Hitler’s expositions could be overcome by proceeding according to plan. From then on, Heim concentrated intensively on the course and content of the conversations at the table; as far as possible, he also unobtrusively noted down a few keywords, occasionally even the one or other striking sentence. With the help of these notes, he then immediately dictated his notes of the conversation to one of Bormann’s secretaries. During the nightly teatimes, however, to which only a small and intimate circle was invited, there was no opportunity to record even a single word. Since this intimate circle often remained gathered around Hitler until the first hours of the following day, the record of the course of conversation could only be dictated the next morning.

In his casual chats, Hitler frequently changed the subject. Initially, therefore, an attempt was made to systematically summarise remarks on certain problem areas over several days.[1] However, since this procedure lost the immediacy of the statement and it was also impossible to reconstruct the context in which the remarks were to be placed, it was quickly abandoned. The conversations were recorded in their course and in the order in which they took place. As a rule, Hitler spoke alone, usually choosing topics that moved him at the time. In many cases, however, he evaded the pressing problems by distancing himself from the work of the day, for example, in reports from his school days or the early days of the NSDAP. Not every monologue Heim recorded advances the reader’s political insight. But all of them provide an insight into the everyday life of the Führer’s headquarters and the mentality and lifestyle of Adolf Hitler.

Martin Bormann was soon very satisfied with Heim’s work. He saw a collection of material emerging to which he attached great importance. In a memo to the Party Chancellery in Munich, he wrote on 20 October 1941: ‘Please keep these – later extremely valuable – notes very well. I have finally got Heim to the point where he is taking detailed notes as a basis for these memos. Any transcript that is not quite accurate will be corrected by me once again!’ As far as can be seen, there was little cause for correction. In the record published here, the head of the Party Chancellery added only a few additions, which are marked in the text of the edition. The extent to which individual objections and remarks were already taken into account in the final transcription of the notes cannot be established with certainty. According to Heim’s statements, this was not the case, and the findings in the files also speak against it. For each talk note, an original was made, which Heim revised and corrected once more. An original with two carbon copies was made of the final version. The first, signed by Heim in each case, was taken by Bormann, the carbon copies were kept by the heads of the political and constitutional departments of the party chancellery. Some notes dictated and signed by Bormann himself were added to the collection.

Heim’s notes begin on 5 July 1941, are interrupted on 12 March 1942, then continued again from 1 August to 7 September 1942. During Heim’s absence, his deputy, Oberregierungsrat Dr Henry Picker, prepared the talk notes from 21 March to 31 July 1942. At the beginning of September 1942, a serious crisis occurred at the Führer’s headquarters. Hitler was disappointed by the lack of success of Army Group A in the Caucasus. He heaped reproaches on the Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal List, and his generals. The Chief of the Wehrmacht Joint Staff, Colonel General Jodl, therefore flew to the Field Marshal’s headquarters to get information about the situation on the fronts of the Army Group. On his return to the Führer’s headquarters on 7 September, he recommended to Hitler a cessation of the attack and a withdrawal of the Mountain Corps, which had been particularly far advanced and weakened by the hard fighting.[2] Hitler reacted angrily and accused Field Marshal List of not following his orders and therefore being responsible for the failure. When Jodl, on the other hand, claimed that the Army Group had strictly followed his instructions and thus indicated that the criticism fell back on Hitler, the rupture was sealed.

The consequence of this serious conflict was that from then on Hitler had the briefings recorded by Reichstag stenographers; did not leave his barracks in daylight for long periods and, in particular, no longer ate with the members of the Führer’s headquarters.[3] To what extent his self-confidence received a severe blow from this event, because he realised that his goals in Russia could no longer be achieved, may remain undiscussed in this context. What is decisive is that Hitler henceforth distrusted his officers and showered them with reproaches that shocked even his closest political confidants.[4] Martin Bormann, too, registered with concern that Hitler was closing himself off more and more from those around him.[5] The transcripts end with the abolition of the common table. If there were still conversations in a relaxed atmosphere afterwards, there was hardly any opportunity to record them. The few notes made in 1943/44 by one of Bormann’s advisers, who also added them to the collection of Führer conversations, are summarised – released for publication – in the fourth part of this volume. A glance at these few documents reveals the change in atmosphere that had taken place since September 1942. Hitler no longer spoke so freely, most questions were only touched on briefly.

Martin Bormann marked his collection of ‘Führer conversations’ as ‘secret’ and sent parts of it to his wife for safekeeping. Gerda Bormann left Obersalzberg on 25 April 1945, after the property had been destroyed in a bombing raid, and took not only her husband’s letters but also the conversation notes with her to South Tyrol. She died there in a prisoner-of-war camp in Merano on 23 March 1946.[6] After the German surrender, an Italian government official in Bolzano took over the entire collection and later sold it to François Genoud in Lausanne, who still owns it. It forms the basis of the present edition.

Martin Bormann marked his collection of ‘Führer conversations’ as ‘secret’ and sent parts of it to his wife for safekeeping. Gerda Bormann left Obersalzberg on 25 April 1945, after the property had been destroyed in a bombing raid, and took not only her husband’s letters but also the conversation notes with her to South Tyrol. She died there in a prisoner-of-war camp in Merano on 23 March 1946.[6] After the German surrender, an Italian government official in Bolzano took over the entire collection and later sold it to François Genoud in Lausanne, who still owns it. It forms the basis of the present edition.

While Henry Picker has meanwhile repeatedly published his conversation notes from the Führer’s headquarters,[7] Heim’s much more extensive notes have so far only been published in foreign languages. A French edition was produced by François Genoud[8] at the beginning of the 1950s; the English edition, by H. R. Trevor-Roper at the same time. This first English edition was followed by a second in 1973; [9] two American editions identical to the English edition had appeared before that.[10] Since these translations of such a central source are much used by international researchers, it is about time that it is finally made accessible in the original text. This is all the more urgent because specific National Socialist terms and also some of Hitler’s linguistic idiosyncrasies can only be translated imperfectly. Attempts to retranslate his remarks have inevitably led to errors that have been to the detriment of the interpretation.

__________

[1] Cf. Gespräch Nr. 28, S. 74.

[2] Colonel General Haider, Kriegstagebuch Vol. III, edited by Hans-Adolf Jacobsen. Stuttgart 1964, p. 518 f. (8. 9. 1942).

[3] Notizen des Generals Warlimont. Kriegstagebuch des OKW, Vol. 2, 1st half volume. Compiled and explained by Andreas Hillgruber. Frankfurt/Main 1963, S. 697.

[4] Heinrich Hoffmann reports on a conversation with Hitler in late summer or autumn 1942, in which Hitler called his officers ‘a pack of mutineers and cowards’. Hoffmann notes: ‘I was deeply affected by this abrupt outburst of hatred. I had never heard Hitler talk like that before’. Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler, wie ich ihn sah. Munich-Berlin 1974, page 178.

[5] Bormann in letters to his wife Jochen von Lang, Der Sekretär. Stuttgart 1977, page 230.

[6] Death certificate of the registry office I in Berlin. Cf. Joseph Wulf, Martin Bormann. Gütersloh 1962, page 223.

[7] Henry Picker, Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier 1941-42 (Hitler’s Table Talks at the Fuehrer’s Headquarters 1941-42), ed. by Gerhard Ritter, Bonn 1951. The second edition was supervised by Percy Ernst Schramm in collaboration with Andreas Hillgruber and Martin Vogt. It appeared in Stuttgart in 1963 and was followed in 1976 by a third new edition edited by Picker himself, published by Seewald-Verlag, Stuttgart. The edition edited by Ritter was published in Milan in 1952 in an Italian translation Conversazioni di Hitler a tavola 1941-1942. Andreas Hillgruber supervised the edition published by Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich, in 1968, and in 1979 Goldmann-Verlag in Munich published a paperback edition edited by Picker.

[8] Adolf Hitler, Libres Propos sur la Guerre et la Paix, recueillis sur l’ordre de Martin Bormann. Paris, 1952 and 1954.

[9] Hitler’s Table Talk 1941-44: His Private Conversations. London 1953 und 1973.

[10] Hitler’s Secret Conversations 1941-1944. New York 1953 and 1961.