Editor’s note: On 18 August 2019 this was originally uploaded as a video in YouTube by YezenIRL under the title ‘Forgiving Game of Thrones: An Unpopular Opinion’:

[Tyrion on the Iron Throne] Disclaimer: The following is not necessarily meant to argue whether or not Season 8 of Game of Thrones was good or bad. But rather to challenge the way we as an audience engaged with the story, and reframe our expectations regarding what value we can take from an imperfect work.

[Tyrion on the Iron Throne] Disclaimer: The following is not necessarily meant to argue whether or not Season 8 of Game of Thrones was good or bad. But rather to challenge the way we as an audience engaged with the story, and reframe our expectations regarding what value we can take from an imperfect work.

Jon: ‘You can forgive all of them. Make them see they made a mistake. Make them understand’.

Dany [Daenerys Targaryen]: ‘I can’t’.

Okay, so I’m back, and we have to talk about Toxic Fandom.

Since Season Eight ended, the internet’s been flooded with countless takes on the ending of Game of Thrones. From fans insisting they know the story better than the writers, to a petition demanding re-shoots, it’s clear that reactions are mixed. And while criticism is important, I think that if we want to be critical of media we should also be critical of our own opinions.

So, in light of some of the extreme reactions we’ve been seeing…

Youtuber: ‘…the worst, the worst, the worst [emphasis in his voice] finale episode in the history of television!’

…I’m gonna say we need to take a step back as a culture, and take a look at ourselves.

[Cersei on the Iron Throne] This kind of reaction isn’t really exclusive to Game of Thrones. Fandoms actually have a history of toxic backlash when things don’t go their way… Now look, I know we all have a right to our opinion and I realise negative opinions are not the same as bullying, but I do have to ask—how much of this is constructive? Do people understand the thing they’re criticising? And, are we maybe overreacting?

[Cersei on the Iron Throne] This kind of reaction isn’t really exclusive to Game of Thrones. Fandoms actually have a history of toxic backlash when things don’t go their way… Now look, I know we all have a right to our opinion and I realise negative opinions are not the same as bullying, but I do have to ask—how much of this is constructive? Do people understand the thing they’re criticising? And, are we maybe overreacting?

Part One: What if we’re overreacting?

It’s hard to talk about fandoms without generalising people, because everyone responds to a story in their own way. Some people loved the ending, some hated it, some hated the ideas, and others hated the way they were executed.

Obviously not everything I say can apply to every single person, so in order to be objective, I’m gonna be a nerd and start with some graphs. Looking at the data, there seems to be a distinct sense from the critical community that Game of Thrones fell apart in the last three or four episodes.

Before that, the show was mostly a critical hit. But was this sudden drop in scores actually fair? For me, the show had been struggling for years to depict organic character development and realistic politics. And to be frank, the books Game of Thrones is based on are way too dense and expansive to be accurately adapted to television. The problem so many had with the ending are problems I’ve been seeing for a while now, and so I’ve come to look at the show as kind of a preview for the books.

[Jorah on the Iron Throne] While I understand people’s frustration with certain sloppily handled twists, I’m also kind of just ‘over it’ and prefer to focus more on the core ideas, like what does the ending say about moral certitude and the glorification of war? Or about power, redemption and choice?

[Jorah on the Iron Throne] While I understand people’s frustration with certain sloppily handled twists, I’m also kind of just ‘over it’ and prefer to focus more on the core ideas, like what does the ending say about moral certitude and the glorification of war? Or about power, redemption and choice?

In the backlash, these bigger discussions aren’t really being had. Yet, the show-runners that fans are now calling ‘Dumb and Dumber’ are the same ones who’ve been writing the show since Season One, and had been receiving critical acclaim well after they passed the books—as we saw with episodes like ‘Battle of the Bastards’ and ‘The Winds of Winter’.

Stannis: ‘A good act does not wash out the bad. Nor a bad the good’.

Though many repeat the mantra that ‘the problem isn’t what happened, it’s how it was executed’, I don’t think that sentiment captures the full story behind the backlash. And that’s not to say that everything was well executed, but to say that for several years fans have been forgiving and even applauding sloppy writing, because they liked what was happening. For example, the resolution of the ‘Slaver’s Bay’ storyline and the ‘Battle of the Bastards’ aren’t really set up much better than anything in Season Eight. They just have more popular outcomes.

What changed in the last three episodes is that the outcomes got controversial. For example, many believed that defeating the Night King was Jon’s whole arc, and insist that Jon was robbed of his destiny. But even before he encountered the White Walkers, Jon’s conflict was always framed as Love versus Duty—the human heart in conflict with itself. His arc is about making difficult choices, not accomplishing great feats. And in that, Jon is still a chosen hero. It’s just that his heroism isn’t supposed to be cool, or honourable, or even triumphant. The point is that doing the right thing isn’t always totally awesome.

[Brienne on the Iron Throne] That kind of subversion is classic Game of Thrones. I mean: if we look to the beginning, Ned’s arc seemed to be going South to become Hand of the King and solve the mystery of Jon Arryn’s murder. Yet, not only does Ned die, he also never figures out who the real killer was. The true arc was Ned’s inner struggle, and like Jon, the legacy of his actions on the world isn’t immediately apparent.

[Brienne on the Iron Throne] That kind of subversion is classic Game of Thrones. I mean: if we look to the beginning, Ned’s arc seemed to be going South to become Hand of the King and solve the mystery of Jon Arryn’s murder. Yet, not only does Ned die, he also never figures out who the real killer was. The true arc was Ned’s inner struggle, and like Jon, the legacy of his actions on the world isn’t immediately apparent.

Tyrion: ‘Ask me again in ten years’.

Not all, but so many of the complaints around the final season come down to some form of ‘this isn’t what I expected’. From the belief that the Night King was the true threat, through the belief that Jon would sit the Iron Throne, to the belief that Jamie’s ending would be more heroic. Which leads us to question: why did the audience have the expectations they did? And what is it about subverted expectations that’s so hard to accept?

Part Two: What if Game of Thrones was never meant to be popular?

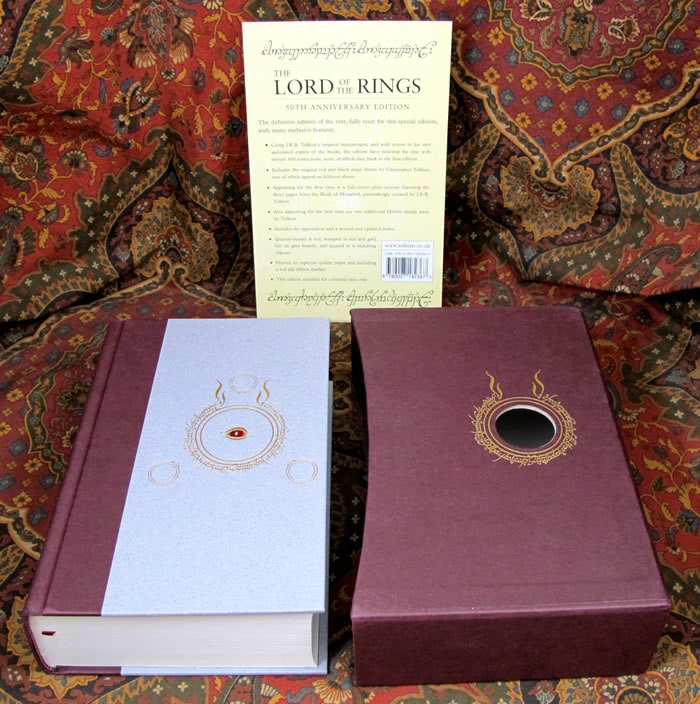

Throughout its eight-year run, Game of Thrones became what can only be described as a landmark television drama, pushing the limits of what a show could accomplish in terms of scope and story, and gaining popularity approaching that of Star Wars, Harry Potter, or the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Simply put, the show reached mainstream status, which is complicated.

So for those who don’t know, Game of Thrones is based on this series of gritty fantasy novels by George R.R. Martin, who’d previously been known for writing really weird niche sci-fi, filled with telepathic hive-minds, body-snatching, and Space Catholicism. The books, as well as the early seasons, trade out straightforward character arcs and cathartic victories for messy, soul-crushing realism. I say this to point out that, unlike Star Wars, Harry Potter or the MCU, Martin’s story was probably never meant to be a big crowd-pleaser.

Shireen: ‘Father, help! Please don’t do this, father!’ [she’s being burned alive at the stake as a plea to the Lord of Light]

But with the growing popularity of the show, Season Six and Seven saw Benioff and Weiss shift gears to a more mainstream narrative. There were probably a lot of reasons for this; some business-related, others to do with the challenges of adaptation. But the story that once built up Joffrey as a villain for four seasons, only to have him poisoned by a relatively minor character, became the show that gave every victory to the fan-favourite character that most wanted it.

So of course people expected Jon and Dany to achieve their goals together. Of course they expected Jaime to save King’s Landing from Cersei. They just watched Sansa execute her rapist, and Arya assassinate everyone who took part in the Red Wedding, and Grey Worm kill the slave masters, and the Stark kids avenge their dad. Suddenly, we were being given a steady stream of good triumphing over evil, and people were eating it up.

So, when we got to the messy George R.R. Martin conclusion, audiences were jarred by the lack of cathartic victory. Thus came a flood of emotions from the fandom. People were upset by the execution and content of what happened, and it became hard to draw the line where one feeling ended and the other began.

[The Hound on the Iron Throne] So people stopped looking past flaws in the show’s execution like they used to, and instead fixated on them directly. After all, people don’t need much justification for stuff like ‘Jon is King now!’ or ‘Dany’s finally coming to Westeros!’ like they do for ‘Jaime goes back to Cersei’. We actually saw this already with Stannis Baratheon, whose tragic ending received highly polarised reactions depending on whether or not viewers had high hopes for the character, with his fans accusing the show-runners of intentional character assassination. And what happened with Stannis is now happening on a much larger scale, with much more popular characters.

[The Hound on the Iron Throne] So people stopped looking past flaws in the show’s execution like they used to, and instead fixated on them directly. After all, people don’t need much justification for stuff like ‘Jon is King now!’ or ‘Dany’s finally coming to Westeros!’ like they do for ‘Jaime goes back to Cersei’. We actually saw this already with Stannis Baratheon, whose tragic ending received highly polarised reactions depending on whether or not viewers had high hopes for the character, with his fans accusing the show-runners of intentional character assassination. And what happened with Stannis is now happening on a much larger scale, with much more popular characters.

While we can say that the tragedies of Ned, Catelyn and Rob were better set up, it’s also important to recognise that, thanks to online spoilers most people knew those characters were doomed within a month of starting the show. So those deaths didn’t really betray the people’s idea of who those characters were or shatter their expectations for what the story was supposed to be…

Due to its emphasis on prophecy and mystery, Game of Thrones actually engages in way more of this kind of theory baiting, with a fan community that’s built on piles of online theory discussions. For millions, speculating about Game of Thrones was a key part of enjoying it. Trust me, as a guy who once wrote a weirdly popular fan theory about Bran possessing Jon’s dead body, I know how it is.

And while that speculation was key to bringing together a dedicated fandom, it also led to fans taking an unwarranted sense of ownership over the story. To get even deeper into it, various fan communities even developed vastly different headcanons and would ridicule each other over their wildly different—and as it turns out—equally incorrect expectations.

[Jaime Lannister on the Iron Throne] People have difficulty accepting that Jon’s parentage is meant to subvert the secret lineage trope, revealing it to be a burden rather than a solution, or accepting that the Night King being defeated before the end is meant to reframe the Dark Lord trope—from being an external evil to an internal consequence of the pursuit of power [the social justice warrior Daenerys Targaryen]. Or accepting that Jamie’s story is an exploration of the limits of redemption arcs.

[Jaime Lannister on the Iron Throne] People have difficulty accepting that Jon’s parentage is meant to subvert the secret lineage trope, revealing it to be a burden rather than a solution, or accepting that the Night King being defeated before the end is meant to reframe the Dark Lord trope—from being an external evil to an internal consequence of the pursuit of power [the social justice warrior Daenerys Targaryen]. Or accepting that Jamie’s story is an exploration of the limits of redemption arcs.

But we also have to bear in mind that Martin came up with the stuff in the 90’s, well before the internet had developed into what it is today. So we can’t blame him for not expecting fans to come to the conclusions that they did.

But it’s fan entitlement that causes literally a hundred percent of misunderstanding being blamed on the writers. At no point are most people accepting that they might have been wrong about anything. This is because people have projected their own ideas of where the story was headed onto the world and characters, and interpreted everything based on those expectations.

[Sansa on the Iron Throne] Basically, I’m saying that people tend to forgive a story that’s sloppily done if it gives them what they wanted. But those same people get hypercritical if a story subverts their expectations in a way that’s upsetting.

[Sansa on the Iron Throne] Basically, I’m saying that people tend to forgive a story that’s sloppily done if it gives them what they wanted. But those same people get hypercritical if a story subverts their expectations in a way that’s upsetting.

Which brings me to my first ever YouTube callout. I’m sure a lot of you have seen [YouTubber] Think Story’s ‘How Game of Thrones Should Have Ended’.

In this video, Think Story recites his fan-fiction of how the story should have played out—abandoning everything subversive and instead just playing out all the most popular fan theories: Jamie kills Cersei; Bran gets stuck in the Night King’s memories; Jon makes the big sacrifice and is remembered as a hero-King, and queen Dany carries forward his legacy. And of course, this video was wildly popular even though it ditches the tough questions Martin asks about war and power, and just offers a conformist fan-fiction about heroes saving the world from [the bad guy of the movies]. So Think Story, thank you for being such a perfect example of mediocrity!

I bring this up because it exposes the entitlement of fandom.

[Samwell on the Iron Throne] Not every story has to please the mainstream. That’s not what Game of Thrones was ever supposed to be. In a world where stories so often fail due to corporate greed, or a lack of creativity, or pandering too hard to a particular demographic, Game of Thrones is actually being punished for the opposite. It’s being punished for keeping through the artistic vision of its author.

[Samwell on the Iron Throne] Not every story has to please the mainstream. That’s not what Game of Thrones was ever supposed to be. In a world where stories so often fail due to corporate greed, or a lack of creativity, or pandering too hard to a particular demographic, Game of Thrones is actually being punished for the opposite. It’s being punished for keeping through the artistic vision of its author.

Part Three: What if I’m wrong?

Ok, so I’ve made some harsh claims. I’ve said that a lot of people’s reactions are being driven by their attachment to an incorrect idea of what the story was supposed to be. As in, I believe the story was always gonna have Jamie choose to die with Cersei, Dany burn King’s Landing, Jon exiled to the Night’s Watch, and Bran chosen as King. That’s the story Martin was always telling, and for the most part, anything else would have been untrue to it.

But what if I’m wrong? Wrong about what’s driving people’s anger, or wrong about the story Martin is telling, or wrong about what’s good?

Jon to Dany in the finale: ‘What about everyone else? All the other people who think they know what’s good?’

Though my channel’s become most widely known for predicting that Bran would be King, I have to admit that over the years I’ve had a ton of theories, and most of them ended up being wrong. Yet, every time, I was so sure that I’d figured things out; that I knew what was good and what this story was supposed to be. Truth is, I’ve always been a little too certain that I’m right about things, and that’s something that I’ve always had to work on, and maybe so do a lot of us.

[Davos on the Iron Throne] And if you notice, that was a big part of the message of Game of Thrones there at the end. That maybe in the process of being so certain that you know what’s good, you aren’t doing anyone any good. Maybe people are out here pointing out plot holes while missing one of the key messages the show tried to deliver; that it’s destructive to be so stuck in our own perspective that we stopped trying to understand.

[Davos on the Iron Throne] And if you notice, that was a big part of the message of Game of Thrones there at the end. That maybe in the process of being so certain that you know what’s good, you aren’t doing anyone any good. Maybe people are out here pointing out plot holes while missing one of the key messages the show tried to deliver; that it’s destructive to be so stuck in our own perspective that we stopped trying to understand.

I mean, does this kind of backlash really benefit anyone? You know, probably not.

I think this need to direct all of our anger at a particular person when we feel let down tends to miss the bigger picture. With Game of Thrones, it’s Benioff and Weiss even though there are much bigger structural issues with adapting A Song of Ice and Fire into a television format. I mean, George R.R. Martin himself splits the story in half for Books Four and Five: a strategy which would have been impossible to do with the television show. Also, he throws in a bunch more characters, and he spent the last eight years writing the sixth book.

Meanwhile, D&D had to not only condense the story, but do it in a fraction of the time. People call them out on rushing the story, but they went one season beyond their initial plan, and spent an entire two years on the final six episodes. They made mistakes, yes, but they did so because they had a hard job…

This is kind of an obvious statement, but television and film is largely driven by the market, and so what gets made will typically be what can reliably turn a profit. On account of just how much goes into shows and movies today, studios avoid taking risks, leading to our current age of remakes, reboots and adaptations.

[Theon on the Iron Throne] When we punish stories that try to be subversive we’re implicitly telling studios to keep playing it safe. So, for better or worse, I appreciate when people have the courage to try something different. We need more different. Frankly, we need more ‘weird’.

[Theon on the Iron Throne] When we punish stories that try to be subversive we’re implicitly telling studios to keep playing it safe. So, for better or worse, I appreciate when people have the courage to try something different. We need more different. Frankly, we need more ‘weird’.

Jon: ‘I think you’re making a terrible mistake’.

Mance Rayder: [smirks] ‘The freedom to make my own mistakes was all I ever wanted’.

Which brings me back to the petition and maybe my most controversial point. In a recent interview, actor Nikolaj Coster-Waldau [Jaime Lannister] joked that the final season of Game of Thrones would be remade once the million people who signed the petition could all agree on an ending. And while he makes a great point about how it’s impossible to appease every headcanon out there, I do want to challenge his point just a little bit.

Because I actually think it would have been easy to make an ending that was better received than the one we got. Which is actually why David Benioff and D.B. Weiss deserve some credit. It would have been easy for them to abandon Martin’s vision and do a crowd-pleasing ending that people were expecting: Have Jon sword-fight the Night King; have Jamie heroically kill Cersei; have Dany install democracy, and then fly off into the sunset with Jon.

An ending like that isn’t hard to come up with. After all, that sort of fan-service and wish fulfilment is pretty much exactly what they wrote for ‘Battle of the Bastards’, and it received widespread acclaim. Seriously people, the last two episodes of Season Six are not well written. People just liked watching the heroes win.

So despite everything, I respect D&D for trying. For doing a final season that took big risks.

Do I think it was great? No! But it was ambitious, and to me that’s more important. Now, of course—of course!—there are things I would have done differently. Characters that I don’t think were handled well, and valid criticisms to make. But, we should consider that for everything that the show-runners might have gotten wrong, there were probably a ton of things we had wrong too. And instead of obsessing over plot holes, maybe our energy would be better spent trying to reach a better understanding. And appreciating that, despite being really flawed, the ending we got was genuine; not focus-grouped or test-marketed, but an attempt to explore some tough questions about who we are. Which is why we should forgive Game of Thrones.

[Varys on the Iron Throne] Although I can’t tell anyone how to feel, I can suggest that we also be self-critical. Though I can’t necessarily tell people what ideals to live by, I do suggest we try to understand the ideals present in the media we consume, and then make a choice whether or not to apply those messages in our own lives. And though it’s up to each of us to choose what we like and what we can forgive, maybe we owe it to ourselves, when our favourite stories let us down, to remember all of the things that made them our favourite stories in the first place.

[Varys on the Iron Throne] Although I can’t tell anyone how to feel, I can suggest that we also be self-critical. Though I can’t necessarily tell people what ideals to live by, I do suggest we try to understand the ideals present in the media we consume, and then make a choice whether or not to apply those messages in our own lives. And though it’s up to each of us to choose what we like and what we can forgive, maybe we owe it to ourselves, when our favourite stories let us down, to remember all of the things that made them our favourite stories in the first place.

Cersei: ‘Our marriage’.

Robert Baratheon: [laughter]

Thanks for watching. [Music]