by Evropa Soberana

Rome

It is incredible the amount of adulterations and trash poured on the history of Rome and the biography of her emperors, but not so much if we think that the Roman Empire faced directly what would later be two very powerful forces: Judaism and Christianity. Rome represented for centuries—as the Macedonians had represented before her—the armed and conquering incarnation of the European will and the vehicle of Indo-European blood in the Near East: in the cradle of the Semitic world, of Judaism, the Neolithic and matriarchy.

In The Anabasis of Alexander Arrian tells us how, being Alexander the Great in Babylon, he received embassies from countless kingdoms of the known world. One of those embassies came from Rome, which at that time was a humble republic headed by a council of elderly patricians, called senators. Alexander saw the customs and behaviour of the Roman ambassadors and, without hesitation, predicted that if his people continued to be faithful to that sober and upright lifestyle, Rome would become a very powerful city.

Before dying, Alexander left in his will that an immense fleet was to be built for, someday in the future, to face the Carthaginian threat which began to take shape on the horizon. Rome, as heir of the Alexandrian mission, also inherited the geopolitical task of wiping out the Carthaginians: a people of Phoenician origin (current Syria, Lebanon and Israel) that had settled in what is now Tunisia. Rome destroyed Carthage in the year 146 BCE, but strong sequels and bad memories remained from that confrontation of the West vs. East, and it would never be the same again.

What struck Alexander about the Roman ambassadors? What made him distinguish them at once from the rest of the ambassadors? That the Romans were an extremely traditional and militarized people, whose life danced to the rhythm of a severe religious ritualism and a disciplined austerity. The Roman religion and Roman customs were present in absolutely every moment of the citizen’s life.

The world, before the eyes of a Roman, was a magical and holy place where the ancient gods, the Numens, the Manes, the Lares, the Penates, the geniuses and infinity of folk spirits, campaigned at ease influencing the lives of the mortals even in their most daily ups and downs (the Civitas Dei of St Augustine, despite attacking the Roman religion, provides valuable information about its complexity).

When the child was born, there was a phrase to invoke a Numen. When the child cried in the crib, another was invoked. It was also prayed for when the child learned to walk, when he came running, when he ran away; when, being a man, he received his baptism of arms, for his wedding, before entering combat, when he fell wounded, by triumphing over the enemy, by returning home victorious, by getting sick, by giving birth to his first child; before eating, before drinking, when sowing the fields…

One Numen was responsible for growing the golden harvests, another Numen (in this case a Numen of Jupiter) precipitated the rain of the sky, another was busy making the grass ripple with the wind; another, in time immemorial, turned the beard of a male family lineage red… All the qualities, all things and all the events, according to the Roman mentality, showed the trace of the creative intervention of the blessed forces of the world, the spirits of the rivers, of the trees, of the forests, of the mountains, of the houses, of the fields…

The families venerated the pater familias and the ancestor of the clan, while every male prided himself on having virtus: a divine quality associated with military prowess, training and combative spirit, and that only young men could possess. Only the flesh of animals sacrificed to the gods were eaten in rituals of uncompromising liturgy; and in religious ceremonies, the simple stammering of a priest was more than enough to invalidate a consecration or have to begin it again.

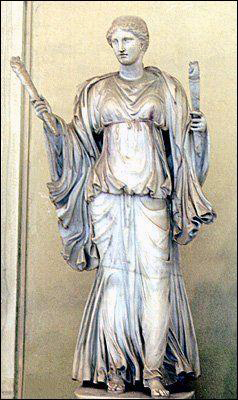

The Roman spirit, represented above by Vesta with two torches, equivalent to the Hellenic Hestia, was a virginal goddess associated with the hearth and fire, which symbolized the centre of the house, around which the family was grouped.

Her priestesses, the Vestals, were virgin girls who, in the interior of their circular temple, watched to see that the sacred fire never went out. There was a law according to which, if a person condemned to death crossed the street with a Vestal, he was acquitted. When some of them failed in their duties they were flogged, and if any transgressed the vow of virginity, they were buried alive. That is just an example of the immense religious seriousness that reigned in the origins of Rome, far removed from the famous ‘decadence of the empire’.

Despite the subsequent influence that Greece had on them, the seriousness with which the Romans took ritualism and folklore was so extreme, and their patriotism so incredible, that we may seriously think that fidelity (what they called the pietas: the fulfilment of duty to the gods in everyday tasks) they professed to the customs and ancestral traditions, was the secret of their immense success as a people. The Romans developed advanced technology and, because of the discipline of their soldiers, the ability of their commanders and a superior way of ‘doing things’ conquered the entire Mediterranean, shielding southern Europe.

If we had to give more examples of peoples in which fidelity to traditions was taken with the extreme gravitas with which it was taken in Rome, only three would be found: two of them are Vedic India and Han China.

The other is the Jewish people.

One reply on “Apocalypse for whites • III”

Arrian himself did not declare that the Romans sent ambassadors to Babylon; he merely mentioned that two writers, Aristus and Asclepiades, claimed that the Romans sent a delegation to Alexander in Babylon. Arrian was not convinced by the suggestion given that no Roman writer had ever mentioned any such delegation, neither had his two principle sources, Aristobulus or Ptolemy. Arrian did not completely dismiss the possibility of that the Romans may have wished to congratulate Alexander in such a way, but given Rome’s historical aversion to kingship, Arrian finds it unlikely.

Perhaps the story was confused with the treaty agreed by Alexander I of Epirus, the uncle of Alexander the Great, and the Romans, following the former’s intervention in Italy on behalf of the Greek city of Taras (Tarentum) in 334 BC. The Epirote king was killed in battle during his campaign in southern Italy while his nephew “waged war on women” in the East.