by Tom Tolland

‘Why do they hate us?’

The president of the United States, in his address to a joint session of Congress, knew that he was speaking for Americans across the country when he asked this question. Nine days earlier, on 11 September, an Islamic group named al-Qaeda had launched a series of devastating attacks against targets in New York and Washington. Planes had been hijacked and then crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Thousands had died. George W. Bush, answering his own question, had no doubt as to the motives of the terrorists. They hated America’s freedoms. Her freedom of religion, her freedom of speech. Yet these were not exclusively American. Rather, they were universal rights. They were as much the patrimony of Muslims as of Christians, of Afghans as of Americans. This was why the hatred felt for Bush and his country across much of the Islamic world was based on misunderstanding. ‘Like most Americans, I just can’t believe it because I know how good we are.’ If American values were universal, shared by humans across the planet, regardless of creed or culture, then it stood to reason that Muslims shared them too. Bush, sitting in judgement on the terrorists who had attacked his country, condemned them not just for hijacking planes, but for hijacking Islam itself. ‘We respect the faith. We honor its traditions. Our enemy does not.’ It was in this spirit that the President, even as he ordered the American war machine to inflict a terrible vengeance on al-Qaeda, aimed to bring to the Muslim world freedoms that he believed in all devoutness to be no less Islamic than they were Western. First in Afghanistan, and then in Iraq, murderous tyrannies were overthrown. Arriving in Baghdad in April 2003, US forces pulled down statues of the deposed dictator. As they waited to be given sweets and flowers by a grateful people, they waited as well to deliver to Iraq the dues of freedom that Bush, a year earlier, had described as applying fully to the entire Islamic world. ‘When it comes to the common rights and needs of men and women, there is no clash of civilizations.’

Except that sweets and flowers were notable by their absence on the streets of Iraq. Instead, the Americans were greeted with mortar attacks, and car bombs, and improvised explosive devices. The country began to dissolve into anarchy. In Europe, where opposition to the invasion of Iraq had been loud and vocal, the insurgency was viewed with often ill-disguised satisfaction. Even before 9/11, there were many who had felt that ‘the United States had it coming’. By 2003, with US troops occupying two Muslim countries, the accusation that Afghanistan and Iraq were the victims of naked imperialism was becoming ever more insistent. What was all the President’s fine talk of freedom if not a smokescreen? As to what it might be hiding, the possibilities were multiple: oil, geopolitics, the interests of Israel. Yet Bush, although a hard-boiled businessman, was not just about the bottom line. He had never thought to hide his truest inspiration. Asked while still a candidate for the presidency to name his favourite thinker, he had answered unhesitatingly: ‘Christ, because he changed my heart.’ Here, unmistakably, was an Evangelical. Bush, in his assumption that the concept of human rights was a universal one, was perfectly sincere. Just as the Evangelicals who fought to abolish the slave trade had done, he took for granted that his own values—confirmed to him in his heart by the Spirit— were values fit for all the world. He no more intended to bring Iraq to Christianity than British Foreign Secretaries, back in the heyday of the Royal Navy’s campaign against slavery, had aimed to convert the Ottoman Empire. His ambition instead was to awaken Muslims to the values within their own religion that would enable them to see everything they had in common with America. ‘Islam, as practised by the vast majority of people, is a peaceful religion, a religion that respects others.’ Bush, asked to describe his own faith, might well have couched it in similar terms. What bigger compliment, then, could he possibly have paid to Muslims?

But Iraqis did not have their hearts opened to the similarity of Islam to American values. Their country continued to burn. To Bush’s critics, his talk of a war against evil appeared grotesquely misapplied. If anyone had done evil, then it was surely the leader of the world’s greatest military power, a man who had used all the stupefying resources at his command to visit death and mayhem on the powerless. In 2004 alone, US forces in Iraq variously bombed a wedding party, flattened an entire city, and were photographed torturing prisoners. [pages 505-507]

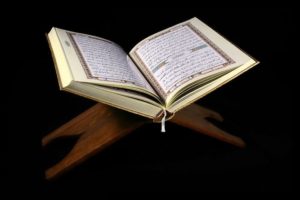

A Qur’an manuscript resting on a rehal.

Three pages further on, Holland continues:

Most menacing of all was the United Nations. Established in the aftermath of the Second World War, its delegates had proclaimed a Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To be a Muslim, though, was to know that humans did not have rights. There was no natural law in Islam. There were only laws authored by God. Muslim countries, by joining the United Nations, had signed up to a host of commitments that derived, not from the Qur’an or the Sunna, but from law codes devised in Christian countries: that there should be equality between men and women; equality between Muslims and non-Muslims; a ban on slavery; a ban on offensive warfare. Such doctrines, al-aqdisi sternly ruled, had no place in Islam. To accept them was to become an apostate. Al-Zarqawi, released from prison in 1999, did not forget al-Maqdisi’s warnings. In 2003, launching his campaign in Iraq, he went for a soft and telling target. On 19 August, a car bomb blew up the United Nations headquarters in the country. The UN’s special representative was crushed to death in his office. Twenty-two others were also killed. Over a hundred were left maimed and wounded. Shortly afterwards, the United Nations withdrew from Iraq.

‘Ours is a war not against a religion, not against the Muslim faith.’ President Bush’s reassurance, offered before the invasion of Iraq, was not one that al-Zarqawi was remotely prepared to accept. What most people in the West meant by Islam and what scholars like al-Maqdisi meant by it were not at all the same thing. What to Bush appeared the markers of its compatibility with Western values appeared to al-Maqdisi a fast-metastasising cancer…

To al-Maqdisi, the spectacle of Muslim governments legislating to uphold equality between men and women, or between Islam and other religions, was a monstrous blasphemy. The whole future of the world was at stake. God’s final revelation, the last chance that humanity had of redeeming itself from damnation, was directly threatened… His [al-Maqdisi’s] incineration by a US jet strike in 2006 did not serve to kill the hydra…

All that counted was the example of the Salaf. When al-Zarqawi’s disciples smashed the statues of pagan gods, they were following the example of Muhammad; when they proclaimed themselves the shock troops of a would-be global empire, they were following the example of the warriors who had humbled Heraclius; when they beheaded enemy combatants, and reintroduced the jizya, and took the women of defeated opponents as slaves, they were doing nothing that the first Muslims had not gloried in. The only road to an uncontaminated future was the road that led back to an unspoilt past. Nothing of the Evangelicals, who had erupted into the Muslim world with their gunboats and their talk of crimes against humanity, was to remain. [pages 510-512]

2 replies on “Dominion, 37”

A brilliant chapter! What I would add, however, is how the 9/11 conspiracy business fits into this picture. It could be viewed as part of the general Christian universalism and arrogance – Muslims could not do it because they are: 1) agency-free sandniggers; 2) hapless victims of evil (=strong) Jews. Another point could be raised as to how people assume bringing war to America to be irrational or unthinkable, so it must be muh’ Jews – because of course the foreign values of revenge and desire for blood are inconceivable to a Christian.

And so it goes that whenever a Christcuck is presented with genuine strong meat, with real examples of foreign cultures, he will scoff at them as “CIA stooges”, he will call them fake, or mad, or will try to see an economic interest where there is none. Only the Christian matrix is allowed.

Yes: another example of Occam’s razor. These guys are incapable of seeing other cultures for what they are. They (including Ron Unz) have to resort to theories that stress credibility to the breaking point instead of accepting the most parsimonious. Sad to say, a liberal like Holland is smarter than most of the racial right.