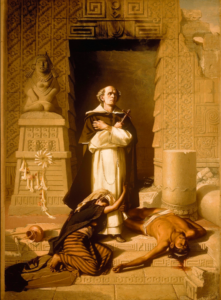

Oil on canvas, 1923 by John Collier.

Month: April 2023

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

To be a Christian was to be a pilgrim. This conviction, widely shared by Protestants, did not imply any nostalgia for the dark days of popery, when monks had gulled the faithful into trekking vast distances to bow and scrape before bogus relics. Rather, it meant to journey through life in the hope that at its end the pilgrim would be met by shining angels, and dressed in raiment that shone like gold, and led into heaven, a city on a hill…

New World, though, was not New England. South of Boston and Plymouth, there was no lack of places where dissenters might settle without fear of harassment. The most visionary of all was a colony named Philadelphia: ‘Brotherly Love’. William Penn, its founder, was a man of paradox. The son of one of Cromwell’s admirals, he was simultaneously a dandy with close links to the royal court, and a Quaker who had repeatedly suffered imprisonment for his beliefs. Philadelphia, the capital of a huge tranche of territory granted Penn by royal charter, was designed to serve as ‘a holy experiment’: a city without stockades, at peace with the local Indians, in which all ‘such as profess faith in Jesus Christ’ might be permitted to hold office. Just as the godly colonies of New England had been founded to serve the whole world as models, so too was Philadelphia—but as a haven of tolerance. By the early eighteenth century, its streets were filled with Anabaptists as well as Quakers, and with Germans as well as English. There were Jews…

In the autumn of 1718, when a Quaker named Benjamin Lay sailed for the Caribbean with his wife, Sarah, he could do so confident that they would literally be among Friends… One day, visiting a Quaker who lived some miles outside Bridgetown, Sarah Lay was shocked to find a naked African suspended outside his house. The man had just been savagely whipped. Blood, dripping from his twitching body, had formed a puddle in the dust. Flies were swarming over his wounds. Like the more than seventy thousand other Africans on Barbados, the man was a slave. The Quaker, explaining to Sarah that he was a runaway, felt no need to apologise. As in the time of Gregory of Nyssa, so in the time of the Lays: slavery was regarded by the overwhelming majority of Christians as being—much like poverty, or war, or sickness—a brutal fact of life. That there was no slave nor free in Christ Jesus did not mean that the distinction itself was abolished. Europeans, who lived on a continent where the institution had largely vanished, rarely thought for that reason to condemn it out of hand. Even Bartolomé de las Casas, whose campaign to redeem the Indians from slavery had become the focus of his entire life, never doubted that servitude might be merited as punishment for certain crimes. In the Caribbean as in Spanish America, the need for workers who could be relied upon to toil in hot and sticky climates without dying of the tropical diseases to which European labourers were prone made the purchase of Africans seem an obvious recourse. No Christian should feel guilt. Abraham had owned slaves. Laws in the Pentateuch regulated their treatment. A letter written by Paul’s followers, but attributed to Paul himself, urged them to obey their owners. ‘Do it, not only when their eye is on you and to win their favour, but with sincerity of heart and reverence for the Lord.’ The punishment of a runaway, then, might well be viewed as God’s work. Even Lay, despite not owning slaves himself, had been known to reach for a whip when other people’s slaves stole from him. ‘Sometimes I could catch them, and then I would give them Stripes.’

Lay, when he remembered bringing down the lash on a starving slave’s back, did not reach for scriptural justifications. On the contrary, he felt only a crushing sense of self-abhorrence. His guilt was that of a man who had suddenly discovered himself to be in the city of Destruction. ‘Oh my Heart has been pained within me many times, to see and hear; and now, now, now, it is so.’ Las Casas, brought to a similar consciousness of his sin, had turned for guidance to the great inheritance of Catholic scholarship: to Cajetan, and Aquinas, and the compilers of canon law. Lay turned for guidance to the Spirit. When he and his wife, fearlessly confronting the slave-owners of Barbados, beseeched them to ‘examine your own Hearts’, it was with an inner certitude as to the ultimate meaning of Scripture. The God that Lay could feel as enlightenment had bought his Chosen People out of slavery in Egypt; his son had washed feet, and suffered a death of humiliating agony, and redeemed all of humanity from servitude. To trade in slaves, to separate them from their children, to whip and rack and roast them, to starve them, to work them to death, to care nothing for the mixing into raw sugar of their ‘Limbs, Bowels and Excrements’, was not to be a Christian, but to be worse than the Devil himself. The more that the Lays, opening their home and their table to starving slaves, learned about slavery, the more furiously they denounced it—and the more unpopular they became. Forced to beat a retreat from Barbados in 1720, they were never to escape the shadow of its horrors. For the rest of their lives, their campaign to abolish slavery—quixotic though it seemed—was to be their pilgrims’ progress.

Benjamin Lay, the four-foot hunchback who devoted his

life to an ultimately successful campaign to persuade his

fellow Quakers to condemn the slave trade.

The image and the text at the bottom of the image appear in Tom Holland’s book.

They were not the first abolitionists in the New World. Back in the 1670s, an Irish Quaker named William Edmundson had toured both Barbados and New England, campaigning to have Christianity taught to African slaves. Then, on 19 September 1676, writing to his fellow Friends in the Rhode Island settlement of Newport, he had been struck by a sudden thought. ‘And many of you count it unlawful to make slaves of the Indians, and if so, then why the Negroes?’ This again was to echo las Casas. The great Spanish campaigner for human rights, in his anxiety to spare Indians enslavement, had for many decades backed the importation of Africans to do forced labour. This he had done under the impression that they were convicts, sold as punishment for their crimes. Then, late in life, he had discovered the terrible truth: that the Africans were unjustly enslaved, and no less the victims of Christian oppression than the Indians. The guilt felt by las Casas, the revulsion and dread of damnation, had been sharpened by the sustenance that he knew he had provided to the argument of Aristotle: that certain races were suited to be slaves. ‘God has made of one blood all nations.’ When William Penn, writing in prison, cited this line of scripture, he had been making precisely the same case as las Casas: that all of humanity had been created equally in God’s image; that to argue for a hierarchy of races was an offence against the very fundamentals of Christ’s teaching; [bold by Ed.] that no peoples were fitted by the colour of their skins to serve as either masters or slaves. Naturally—since this was an argument that so selfevidently went with the grain of Christian tradition—it was capable of provoking some anxiety among the owners of African slaves. Just as opponents of the Dominican had cited Aristotle, so opponents of Quaker abolitionists might grope after obscure verses in the Old Testament.

Yet Lay’s campaign, for all that it drew on the example of the prophets, and for all that his admonitions against slavery were garlanded with biblical references, did indeed constitute something different. To target it for abolition was to endow society itself with the character of a pilgrim, bound upon a continuous journey, away from sinfulness towards the light… It was founded upon the conviction that had for centuries, in the lands of the Christian West, served as the great incubator of revolution: that society might be born again. ‘Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit.’

Never once did Lay despair of these words of Jesus. Twenty years after he had gatecrashed the annual assembly of Philadelphia Friends, as he lay mortally sick in bed, he was brought news that a new assembly had voted to discipline any Quaker who traded in slaves. ‘I can now die in peace,’ he sighed in relief… Benjamin Lay had succeeded, by the time of his death in 1759, in making the community in which he had lived just that little bit more like him—in making it just that little bit more progressive. [pages 379-386]

Quotable quote

‘I don’t think the current implosion of the global economy allows for a successful technocratic social credit totalitarianism.’

—Benjamin

Dominion, 23

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

So far I have collected some passages from the ‘Antiquity’ and ‘Christendom’ sections of Tom Holland’s book. The last section is entitled ‘Modernitas’ and begins with a chapter on Reformed England.

Oliver Cromwell c. 1655 by Samuel Cooper.

In England, where the self-identification of Puritans as the new Israel had fostered a boom in the study of Hebrew, this might on occasion shade almost into admiration. Even before Menasseh’s arrival in London…

The rabbi Menasseh ben Israel travelled from Amsterdam to London to beg that Jews be granted a legal right of residency in England.

…there were sectarians who claimed it a sin ‘that the Jews were not allowed the open profession and exercise of their religion amongst us’. Some warned that God’s anger was bound to fall on England unless repentance was shown for their expulsion. Others demanded their readmission so that they might the more easily be won for Christ, and thereby expedite the end of days. Cromwell, who convened an entire conference in Whitehall to debate Menasseh’s request, was sympathetic to this perspective. Nevertheless, he failed to win formal backing for it. Accordingly—in typical fashion—he opted for compromise. Written permission for the Jews to settle in England was denied; but Cromwell did give Menasseh the private nod, and a pension of a hundred pounds…

The refusal of Cromwell to grant them a formal right of admission prompted missionaries to head for Amsterdam. The early signs were not promising. The Jews there seemed resolutely uninterested in the Quakers’ message; the authorities were hostile; only one of the missionaries spoke Dutch. Nevertheless, it was not the Quaker way to despair. There was, so one of the missionaries reported, ‘a spark in many of the Jews’ bosoms, which in process of time may kindle to a burning flame’…

A second pamphlet, A Loving Salutation to the Seed of Abraham Among the Jews, quickly followed. Anxious to get both tracts into Hebrew, the Quaker missionaries in Amsterdam were delighted to report back to Fell that they had successfully procured the services of a translator. This translator was not only a skilled linguist; he had also been a pupil of none other than Menasseh himself. [pages 372-374]

This Jew was none other than Baruch Spinoza. Protestant Christians were instrumental in reversing the ban on Jews. Soon after, they returned to England.

Read David Irving’s introduction to Hitler’s War here.

Dominion, 22

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

The fall of Mexico to Christian arms had been followed by the subjugation of other fantastical lands: of Peru, of Brazil, and of islands named—in honour of Philip II—the Philippines. That God had ordained these conquests, and that Christians had not merely a right but a duty to prosecute them, remained, for many, a devout conviction. Idolatry, human sacrifice and all the other foul excrescences of paganism were still widely cited as justifications for Spain’s globe-spanning empire. The venerable doctrine of Aristotle—that it was to the benefit of barbarians to be ruled by ‘civilised and virtuous princes’—continued to be affirmed by theologians in Christian robes.

There was, though, an alternative way of interpreting Aristotle. In 1550, in a debate held in the Spanish city of Valladolid on whether or not the Indians were entitled to self-government, the aged Bartolomé de las Casas had more than held his own. Who were the true barbarians, he had demanded: the Indians, a people ‘gentle, patient and humble’, or the Spanish conquerors, whose lust for gold and silver was no less ravening than their cruelty? Pagan or not, every human being had been made equally by God and endowed by him with the same spark of reason. To argue, as las Casas’ opponent had done, that the Indians were as inferior to the Spaniards as monkeys were to men was a blasphemy, plain and simple. [bold added by Ed.]

‘All the peoples of the world are humans, and there is only one definition of all humans and of each one, that is that they are rational.’ Every mortal—Christian or not—had rights that derived from God. Derechos humanos, las Casas had termed them: ‘human rights’. [bold added by Ed.] It was difficult for any Christians who accepted such a concept to believe themselves superior to pagans simply by virtue of being Christian. The vastness of the world, not to mention the seemingly infinite nature of the peoples who inhabited it, served missionaries both as an incentive and as an admonition. [pages 346-347]

Bartolomé de las Casas was my father’s idol in the last decades of his life, to the extent that he composed La Santa Furia, a symphonic work accompanied by more than a hundred voices and a theatrical performance, which was premiered five years ago (watch it on YouTube here). After the premiere, I wrote a harsh critique of my father’s last symphonic work, which reflects the core of my thinking (an even harsher critique can be found on pages 376-388 of El Grial).

My father died before the premiere of his magnum opus. Among his descendants there is still a son and one of his grandsons who, because of La Santa Furia, believe in the myth of Bartolomé de las Casas: one of the founders of the black legend against Spain.

Guilt. Guilt. Guilt. See Félix Parra Hernández’s (1845–1919) painting above. That is the malware that Christian ethics installed in the white man’s soul (e.g., there are European Dominicans lobbying the Vatican to canonise Las Casas).

“Are intelligent machines a threat?” Penrose asks rhetorically, and answers in the negative because “such devices will not be intelligent”.

by Tom Holland

That October, as the people of Leiden celebrated their liberation from the Spanish, and Reformed preachers pushed with ever more determination for their country to serve worthily as a new Israel, war was threatening the Protestants of the Rhineland and Bohemia. As in the days of Žižka, a Catholic emperor had mustered armies to march on Prague. His ambition: to extirpate Protestantism…

The centre did not hold. On 8 November, the Protestant forces on White Mountain were broken. Prague fell the same day. The war, though, was far from over. Quite the opposite. It was only just beginning. Like the blades of a terrible and revolving machine, the rivalries of Catholic and Protestant princes continued to scythe, mangling ever more reaches of the empire, sucking into the mulch of corpses ever more foreign armies, turning and ever turning, and only stopping at last after thirty years. Christian teachings, far from blunting hatreds, seemed a whetstone. Millions perished. Wolves prowled through the ruins of burnt towns. Atrocities of an order so terrible that, as one pastor put it, ‘those who come after us will never believe what miseries we have suffered’, were committed on a numbing scale: men castrated; women roasted in ovens; little children led around on ropes like dogs…

To many in the killing fields of Germany and central Europe, it seemed that the roots of the Republic’s greatness were being fed by blood. Munitions, and iron, and the bills of exchange that funded the rival armies: all were monopolised by Dutch entrepreneurs. The great dream of the godly—that by their example they might inspire anguish-torn humanity to reach out to the joy and the regeneration that only divine grace could ever provide—was shadowed by the nightmare of a Christendom being torn to pieces…

On 9 November 1620, one day after the battle of the White Mountain, a ship named the Mayflower arrived off a thin spit of land in the northern reaches of the New World. Crammed into its holds were a hundred passengers who, in the words of one of them, had made the gruelling two-month voyage across the Atlantic because ‘they knew they were pilgrims’—and of these ‘pilgrims’, half had set out from Leiden. These voyagers, though, were not Dutch, but English. Leiden had been only a waypoint on a longer journey: one that had begun in an England that had come to seem to the pilgrims pestiferous with sin. First, in 1607, they had left their native land; then, sailing for the New World thirteen years later, they had turned their backs on Leiden as well. Not even the godly republic of the Dutch had been able to satisfy their yearning for purity, for a sense of harmony with the divine. The Pilgrims did not doubt the scale of the challenge they faced. They perfectly appreciated that the new England which it was their ambition to found would, if they were not on their mettle, succumb no less readily to sin than the old. Yet it offered them a breathing space: a chance to consecrate themselves as a new Israel on virgin soil…

John Winthrop

Too much was at stake. It being the responsibility of elected magistrates to guide a colony along its path to godliness, only those who were visibly sanctified could possibly be allowed a vote. ‘The covenant between you and us,’ Winthrop told his electorate, ‘is the oath you have taken of us, which is to this purpose, that we shall govern you and judge your causes by the rules of God’s laws and our own, according to our best skill.’ The charge was a formidable one: to chastise and encourage God’s people much as the prophets of ancient Israel had done, in the absolute assurance that their understanding of scripture was correct. No effort was spared in staying true to this mission. Sometimes it might be expressed in the most literal manner possible. In 1638, when settlers founded a colony at New Haven, they modelled it directly on the plan of an encampment that God had provided to Moses. [pages 340-343]

Computers can’t think

Responding to Adunai:

You have the mental block, not me. You got to read Roger Penrose to see what we mean. No computer to date has more consciousness than a washing machine.

P.S. The Penrose book I read is The Large, the Small and the Human Mind. Fascinating philosophy of science!

Dominion, 20

Or:

How the Woke monster originated

Henry VIII—who, as king of England, lived in fuming resentment of the much greater prestige enjoyed by the emperor and the king of France—had been mightily pleased to have negotiated the title of Defender of the Faith for himself from Rome. It had not taken long, though, for relations between him and the papacy to take a spectacular turn for the worse. In 1527, depressed by a lack of sons and obsessed by a young noblewoman named Anne Boleyn, Henry convinced himself that God had cursed his marriage. As wilful as he was autocratic, he demanded an annulment. The pope refused. Not only was Henry’s case one to make any respectable canon lawyer snort, but his wife, Catherine of Aragon, was the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella—which meant in turn that she was the aunt of Charles V. Anxious though the pope might be to keep the English king on side, his prime concern was not to offend Christendom’s most powerful monarch. Henry, under normal circumstances, would have had little option but to admit defeat. The circumstances, though, were hardly normal. Henry had an alternative recourse to hand. He did not have to accept Luther’s views on grace or scripture to relish the reformer’s hostility to the pope. Opportunistic to the point of megalomania, the king seized his chance. In 1534, papal authority was formally repudiated by act of parliament. Henry was declared ‘the only supreme head on Earth of the Church of England’. Anyone who disputed his right to this title was guilty of capital treason. [pages 324-325]

‘Where the Spirit of the Lord is,’ Paul had written to the Corinthians, ‘there is freedom.’ Between this assertion and the insistence that there existed only the one way to God, only the one truth, only the one life, there had always been a tension. The genius of Gregory VII and his fellow radicals had been to attempt its resolution with a programme of reform so far-reaching that the whole of Christendom had been set by it upon a new and decisive course. Yet the claim of the papacy to embody both the ideal of liberty and the principle of authority had never been universally accepted. For centuries, various groups of Christians had been defying its jurisdiction by making appeal to the Spirit. Luther had lit the match—but others before him had laid the trail of gunpowder. This was why, in the wake of his defiant appearance at Worms, he found himself impotent to control the explosions that he had done so much to set in train. Nor was he alone. Every claim by a reformer to an authority over his fellow Christians might be met by appeals to the Spirit; every appeal to the Spirit by a claim to authority. The consequence, detonating across entire reaches of Christendom, was a veritable chain reaction of protest.

Flailingly, five Lutheran princes had sought to put this process on an official footing. In 1529, summoned to an imperial diet, they had dared to object to measures passed there by the Catholic majority by issuing a formal ‘Protestation’. By 1546, when Luther died, commending his spirit into the hands of the God of Truth, other princes too had come to be seen as ‘Protestant’—and not only in the empire. Denmark had been Lutheran since 1537; Sweden was well on its way to becoming so…

Certainly, in the years that followed Luther’s death, the task of steering the great project of reformatio between rocks and shoals appeared an ever more desperate one. Lutheran princes were crushed in battle by Charles V, and cities that had long echoed to the impassioned debates of rival reformers brought to submit. Many exiles, in their desperation to find sanctuary, headed for England, where—following the death of Henry VIII in 1547—his young son, Edward VI, had come to be hailed by Protestants as a new Josiah. This was no idle flattery…

…Mary, the daughter of Catherine of Aragon. Devoutly Catholic, it did not take her long to reconcile England with Rome. Many leading reformers were burned; others fled abroad. The lesson to Protestants on the perils of placing their trust in a secular authority was a harsh one. Yet there was peril too in being a stateless exile. To refugees in flight from Mary’s England, it seemed an impossible circle to square. The liberty to worship in a manner pleasing to God was nothing without the discipline required to preserve it—but how were they to be combined? Was it possible, amid the storms and tempests of the age, for a seaworthy ark to be built at all? [pages 327-329]

A couple of pages later Tom Holland starts talking about John Calvin, from which I would just like to quote this passage:

The shelter that the city could offer refugees was like streams of water to a panting deer. Charity lay at the heart of Calvin’s vision. Even a Jew, if he needed assistance, might be given it. ‘Remember this: Whoever sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and whoever sows generously will also reap generously.’ The readiness of Geneva to offer succour to refugees was, for Calvin, a critical measure of his success. He never doubted that many Genevans profoundly resented the influx of impecunious foreigners into their city. But nor did he ever question his responsibility to educate them anew. The achievement of Geneva in hosting vast numbers of refugees was to prove a momentous one. [pages 331-332]

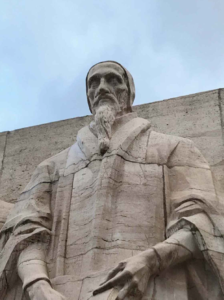

John Calvin, as portrayed on the Reformation Wall

built in Geneva to commemorate the four-hundredth

anniversary of his birth. ‘If you desire to have me as

your pastor,’ he told the people of his adopted city,

‘then you will have to correct the disorder of your lives.’

The above image and accompanying text appears in colour in Tom Holland’s book. As we saw in a previous entry of this series in which Spanish Catholics admitted baptised Jews into their kingdoms after the expulsion of the unconverted, the Protestant counterpart made the same mistake: all based on Christian piety (‘Even a Jew, if he needed assistance, might be given it.’).

The subsequent history of Europe speaks for itself. It was not the Jews who empowered themselves: it was the Christians and later the French Jacobins (whom I call neochristians since Jacobins, Catholics and Protestants share the same axiological system) who did so.