Given the uncompromisingness in the implementation of his ideological goals, Hitler encountered permanent resistance from all opposing forces in Europe. The struggle against communists, socialists and pacifists, waged from the beginning, became steadily tougher during the war. More complicated was the confrontation with the liberal and conservative forces of the bourgeoisie, who expressed more and more reservations as the war progressed and circumvented or delayed numerous orders. They could rarely be forced or ousted because they could not be replaced as experts in their fields of activity. Disgruntled by this, Hitler repeatedly criticised civil servants, teachers, professors and intellectuals who did not take into account the requirements of the time.

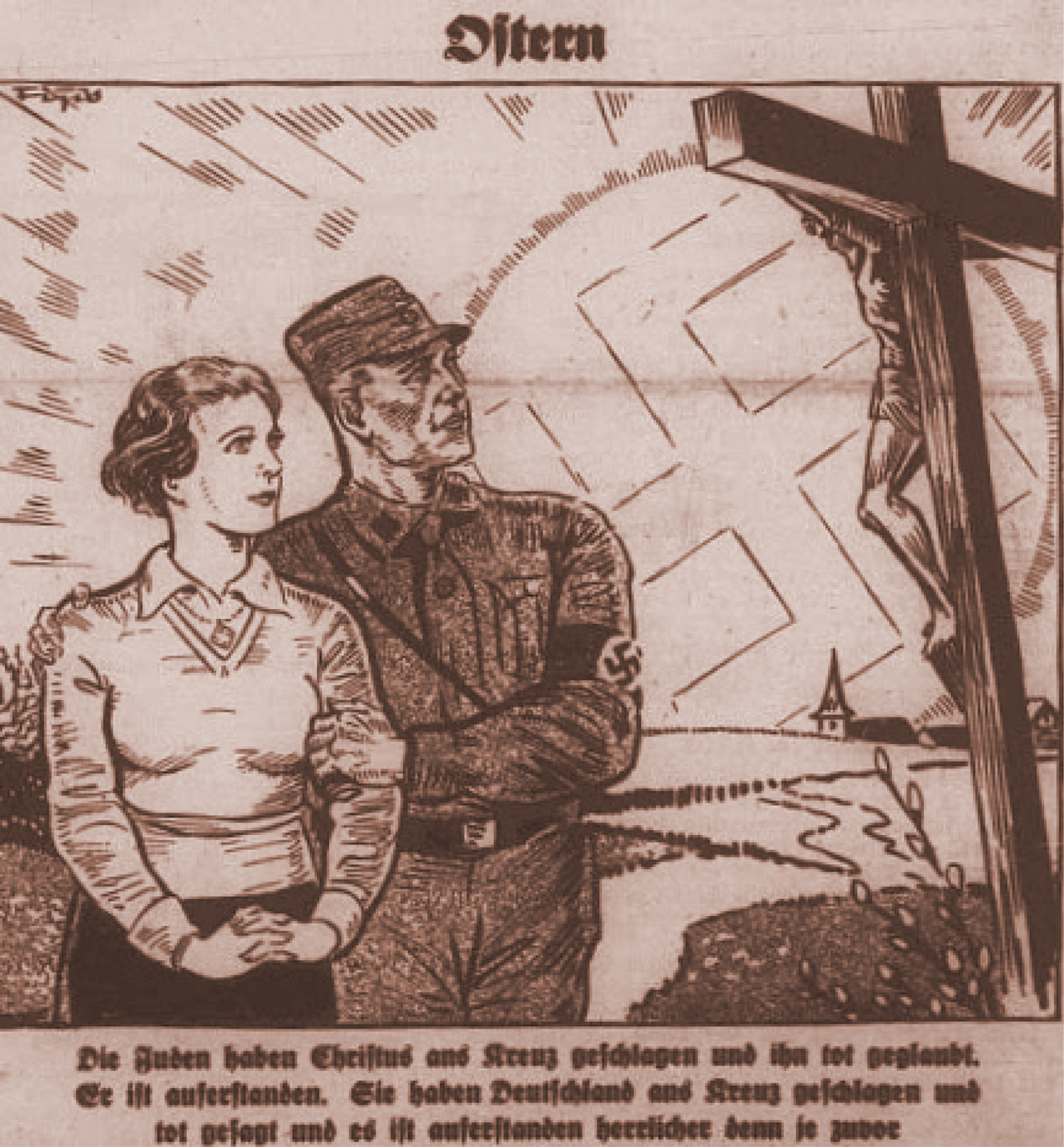

The intensification of the Weltanschauungskampf (worldview struggle) is particularly evident in the accusations against Christianity and the Christian churches. Since Christians fundamentally respect every human being as a creature of God, many of them rebelled against the practices of racial, ethnic and occupation policies when they realised that these were not temporary exaggerations or excesses, but a planned approach. Not only the small group of those who actively resisted became a danger for the National Socialist leadership, but also the constantly growing number of Christians who, out of conscientious objection, refused the regime in whole or in part.

The accusations against the churches and Christianity were so sharp not least because Hitler was by no means areligious and believed in a Creator, but in contrast to the Christians was convinced that he knew and could do His will. From his point of view, the churches were acting completely unnaturally by observing the commandment of love, which included the incurably ill, people of different skin colour and race, and unbelievers. For him, therefore, Christianity was ‘pre-Bolshevism’ (table talk #40). In Hitler’s view, Paul had transformed and used the teachings of Christ to undermine and bring down the Roman Empire from within. Through the demand for equality of all people, the uprising of the lowly and the inferior had been initiated: the ground was prepared for overthrow and destruction. ‘Pure Christianity’, Hitler concluded, ‘leads to the destruction of humanity, it is naked Bolshevism in metaphysical dressing’ (table talk #66).

The verbal radicalism of the attacks against Christianity was also determined by the fact that Hitler knew exactly that he could not wage a determined church struggle during the war. He was well aware of the power that the churches still represented. A great conflict, therefore, was bound to lead to deep anxiety among the population and evoke great dangers during the war. Therefore, it seemed advisable merely to register the opposition of the bishops, clergy and church laity and to postpone the reckoning until a later time (# 130).

Hitler’s sharp front against Christianity was by no means approved of by all, even within the NSDAP and its branches. Ministers who had gained their office through the party broke ranks. Even in the SS there were still leaders and members who had not left the church and who were bound to come into serious conflict in the event of a dispute. It was no different in the corps of political leaders up to the highest ranks. This example—others could be brought up—shows that the NSDAP was not a monolithic bloc, and that there was no basic consensus even on decisive questions. In the Weltanschauungskampf Hitler could not rely unconditionally on his party; rather, he was dependent on other forces and power-bearers to carry out his plans and orders.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s Note: This wonderfully shows that it was not time to wage war! It was time to consolidate the Nazi state and educate the masses about Christianity: something that white nationalists across the Atlantic haven’t yet managed to do. (That’s why I consider them semi-normies, as I said yesterday.)

______ 卐 ______

But other groups of Germans were certainly not unreservedly prepared to make the goals of the National Socialist state their own. In Hitler’s national community (Volksgemeinschaft), the social contradictions and the old ideals were by no means overcome, as has been shown, but only pushed back; they broke out again when rapid rearmament and military expansion overstretched popular forces. Even before the war began, the enthusiasm of the national bourgeoisie that it had shown in the face of the reintroduction of universal conscription and the foreign policy successes of the Third Reich was waning. Regimentation, growing restrictions on economic, intellectual and cultural activity and the constant threat of external conflict led to a revival of faded principles. The working class, which to a large extent had recognised the efforts to revive the economy as well as the improvement of social benefits, increasingly rebelled against the restrictions on the choice of employment and the enforcement of their wage demands. The more powerless they felt in the face of decisions to extend working hours and worsen employment conditions, the more they became aware of the disintegration of trade union organisations.

In Hitler’s thinking, ideological goals had absolute priority, so he ignored the concerns and wishes of the population as soon as his rule was securely established. His regime became uncompromising, the subordinate leaders and generals were to be ‘ice-cold dog snouts’ and ‘unpleasant people’ (#98) when it came to accomplishing the tasks set. Convinced of the rightness of what he was striving for, he allowed no leniency or forbearance. He understood people with their faults and weaknesses, but forbade himself and others to take them into account. His regime was not in the service of the people, but the people were made to serve his worldview.

In recent years, various attempts have been made to revise the image of Hitler. According to them, the leader of the Third Reich appears as the man of peace, the patron of the arts and the builder of a new, more beautiful Europe.[1] Evidence for these theses can certainly be found in the monologues published here. And there is no doubt that Hitler knew how to win over and inspire people for himself and his goals right up to the end. But anyone who reads these conversation notes carefully, cannot ignore the fact that he wanted to build the happiness of future generations on the misfortune of those whom he declared enemies or who did not act and believe as he did. On the way to his future, not only enemies but also enthusiastic followers and faithful followers were left behind as victims.

_________

[1] I will mention here only one book, representative of many others, by the architect Hermann Giesler: Ein anderer Hitler. Erlebnisse–Gespräche–Reflexionen. Leoni am Starnberger See, 1978.

2 replies on “The Führer’s monologues (viii)”

Most Conservative Christians in America idolise the Communist Subversive, Bonhoeffer. J.D. Hall, William Lane Craig, Eric Metaxas, John MacArthur, et al.

Christians boast about how they did everything in their power to destroy the third Reich and to assassinate Hitler. Nazi Germany would have probably been a glorious thousand-year Reich were it not for Christian subversives like Bonhoeffer and Pius XI.

Yeah, Hitler should have consolidated power in Germany rather than starting a World War.

He didn’t start a world war. He started a war with Poland.

The fucking Anglos then escalated it into a European war.

This began a domino effect which then led to a War of Extermination carried out by the Egalitarian Soviets and the Neochristian Americans.

If Hitler hadn’t started the war with Poland, the three U’s (UK, USSR, USA) would eventually concoct a plan to start a war which involved the third Reich. They were never going to allow Hitler to continue consolidating power. War was inevitable.

It’s all part of a game of Hegemony – as explained by Mearsheimer.