The pre-Rockwell years (1946-1958)

For good or for ill, the German American Bund was the primary exponent of open National Socialism in the US before America entered the War. After the voluntary dissolution of the Bund on December 8, 1941, there was no open advocacy of the National Socialist worldview in the US until George Lincoln Rockwell raised the Swastika banner in Arlington, Virginia, on March 8, 1959. The option to re-found the Movement was theoretically available as soon as the War had ended in 1945. However, the immediate post-War political and social climate was so hostile to National Socialism that even the most stalwart American National Socialists were unwilling to take that path forward.

But still, the struggle went on, albeit in the political shadows, rather than in the light of day. Various pro-NS or neo-NS activist groups arose during the pre-Rockwell period that attempted to advance the Cause without openly declaring themselves to be National Socialist.

There is a great divide – really, a chasm – that divides the pre-War Movement from the post-War Movement. To a degree this separation is one of ideology: the world was a much different place in the 1950s than it was in the 1930s, and it was a natural and organic development that the Movement’s policies evolved to fit the new dispensation.

But the real differences are those of quantity and quality. If pre-War American National Socialism was, at best, a minor movement on the American political scene, it became microscopic in its numbers in the post-War period. The Bund had 25,000 members at its height, of whom 3,000 were uninformed activists. In contrast, the National Socialist White People’s Party at its strongest in the early 1970s never had more than 800 supporters and 200 Stormtroopers. Adjusted for population growth, this meant that the NSWPP had about two per cent of the Bund’s numerical strength relative to the total US population, and perhaps three per cent of its activists.

It can be said that both the pre-War and post-War movements were led by men who were fanatically committed to the Cause, who were intelligent, and who and possessed stable personalities. But the pre-War Movement’s rank-and-file members were also of similar quality: men with careers, families, marriages, community standing and the like. In contrast, the fringe nature of the post-War Movement often meant that its rank-and-file adherents had eccentric personalities, and frequently lived on the edges of American society. This is especially true of the Movement’s activist contingent. There were, of course, a percentage of rank-and-file supporters who had successful lives in society’s mainstream. But normally these comrades kept a low profile and played a passive role rather than an active one.

The Columbians

On August 18, 1946, Emory Burke, along with Henry Loomis and John Zimmerlee, incorporated the ‘Columbians Workers Movement of America’ in Georgia. It was commonly referred to simply as ‘the Columbians’. Although short-lived, the Columbians was the first attempt to rebuild the Movement after the catastrophe of 1945.

Burke was a National Socialist at heart, but he realized that with the War barely a year over, open advocacy of the Hitlerian worldview was a non-starter. Rather, something in line with American traditions and values would have a greater chance of success.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: This was a gigantic mistake by the American racialists, and it persists to this day.

The correct way would have been, as I have said, to found a publishing house for books like Hellstorm: The Death of Nazi Germany, 1944-1947, which decades later Tom Goodrich would write. All the information was already there, in the 1940s (Goodrich’s sources!). The sources only had to be cited in emotive books like Goodrich’s to show that the Allied narrative about the war was a hoax.

But they didn’t. Today’s westerners still ignore that the Allies committed a real Holocaust of Germans after 1945. The blame lies entirely with these Americans who didn’t want to do astute metapolitics (Goodrich-like books) but activism—a fool’s errand because of the media brainwash of the masses.

______ 卐 ______

What he had in mind was a dynamic racial movement, something more political than the Ku Klux Klan and more racially focused than Christian Nationalism. Burke was a veteran of numerous pre-War organizations, and he was still in contact with leaders of the old movement who still had some fight left in them, such as George Deatherage, Gerald L.K. Smith, and Gen. George Van Horn Moseley. However, he also attracted recruits who had only come of age since the War. One of these was a young attorney from Chattanooga named J.B. Stoner; another was high school student Edward Reed Fields, transplanted to Atlanta from Chicago. Although neither of these two young men would play a significant role in the Columbians, the racialist movement would hear more from them in the years to come.

Burke and his comrades spent several months in preparation before publicly launching their new enterprise. In June 1947, they were ready. A headquarters had been secured in Atlanta, and the first issue of a newsletter, The Thunderbolt, had been issued, along with a program. Following in the steps of the pre-War movement, the Columbians had a uniform: khaki, with a red thunderbolt insignia on the left arm. The thunderbolt was also featured on their banner, which was patterned after the Confederate battle flag.

The Columbians held meetings and made a concerted effort to attract White workers and recently demobilized soldiers. In July, they began night-time patrols of White working-class neighbourhoods that were bordered by Negro areas: Blacks criminals, who had historically preyed on other Negroes, had begun to drift into White neighbourhoods after the sun went down.

The rise of the Columbians disturbed the political establishment of Atlanta, and it scared the city’s large and powerful Jewish community. After an incident in which a Columbian patrol injured a Black man found wandering at night through a White neighbourhood, the authorities cracked down on the group. Its leaders, including Burke, were arrested on charges of ‘usurping police powers’ – that is, conducting a citizens’ patrol to do a job that the police were failing to do. Burke was sentenced to prison, and the charter of the Columbians was revoked.

The Columbians were in operation only a scant two months. Their total membership numbered less than 200, of whom only a couple dozen were actively involved. Yet their example inspired racial nationalists elsewhere. Slowly, the Movement was beginning to reawaken.

National Renaissance Party

Before describing the National Renaissance Party, a cautionary note is necessary: Almost without exception, everything that may be found online or in printed books concerning the NRP and its leader, James H. Madole, is flat-out wrong. Wikipedia has collected the most egregious falsehoods about the NRP and exaggerated them further, and then published them as the truth. Virtually nothing that you may have heard about the NRP from such sources is correct.

The National Renaissance Party was officially founded on January 1, 1949, following several months of negotiations among various minor leaders of the pre-War movement who decided to combine their meagre memberships and resources into a single new group. The main groups involved were Kurt Mertig’s Citizens Protective League, the German-American Republican League (also led by Mertig) and William Henry MacFarland’s Nationalist Action League. Mertig was named as the chairman of the group, but it was under the operational control of 22-year-old James Harting Madole, a new post-War recruit.

Madole was brilliant, energetic, fearless and an effective public speaker. One of his contacts was Charles B. Hudson, who had been a defendant in the 1944 Sedition Trial described previously. Hudson shared Madoles’s interests in racial nationalist politics, space travel, science fiction and the occult. And here we come to one of Madole’s shortcomings: his trouble in separating his enthusiasms from his political career. However, this problem only manifested itself later, in the 1970s, and was not a handicap during the NRP’s early years.

Madole’s title was National Director, and he held the real power within the small party. A nine-point program was drafted, stationery was printed up, and the first issue of the party’s publication, the National Renaissance Bulletin was issued. The lead article of the inaugural issue ‘Americans, Awake’, was authored by Madole. He continued to issue the newsletter without interruption until death in 1979.

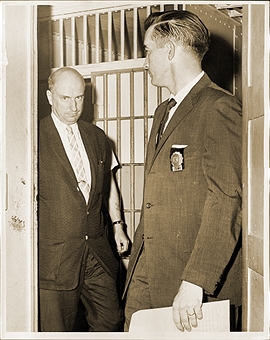

(James Madole, left.) From the very beginning, the NRP showed itself to be different from many of the pre-War NS and Christian Nationalist groups, in that it took a serious interest in ideas and ideologies. Madole’s goal was to build a new Aryan super-civilisation in North America, not just to save the Constitution from the Jews. He was anti-rightwing, anti-capitalist and anti-Christian, all of which earned him the hostility of the Christian Nationalists and their allies, such as the Ku Klux Klan.

(James Madole, left.) From the very beginning, the NRP showed itself to be different from many of the pre-War NS and Christian Nationalist groups, in that it took a serious interest in ideas and ideologies. Madole’s goal was to build a new Aryan super-civilisation in North America, not just to save the Constitution from the Jews. He was anti-rightwing, anti-capitalist and anti-Christian, all of which earned him the hostility of the Christian Nationalists and their allies, such as the Ku Klux Klan.

An early NRP associate was Francis Parker Yockey, who attended NRP meetings and activities, although he never officially became a member. Madole shared Yockey’s assessment that Stalin had broken the power of the Jewish-Bolsheviks in the USSR, and was steering the Soviet Union ever-closer to the traditional Russia of the czars. Whereas the mainstream view of the Soviets in the West during the Cold War was that they were ideologically monolithic, Madole perceived that there was a behind-the-scenes struggle taking place between the remaining Jewish Marxists on one hand, and Russian nationalists on the other. The smart thing, Madole felt, was to encourage the nationalists within the Soviet regime, and forge an alliance with them, which he tried to do. This nuanced appraisal of the USSR was lost on the American Right of the 1950s, who decided that Madole was just a racist, anti-Semitic communist.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: This flaw would also appear among some white nationalists of the next century with their mad infatuation with Putin’s Russia.

______ 卐 ______

The NRP never defined itself as National Socialist, although it praised Adolf Hitler and NS Germany. In the early years, the NRP used both Swastikas and thunderbolts on its printed material. Initially, the NRP did not have a uniformed, paramilitary section. However, repeated efforts by its opponents to disrupt NRP public activities convinced Madole that such a formation was needed, and in 1953 he formed the ‘Elite Guard’, who wore black uniforms with thunderbolt armbands. The EG was under the joint command of Hans Schmidt and an 18-year-old Matt Koehl, who was just beginning his apprenticeship in NS politics.

From the very beginning, the NRP had an aggressive program of public activities. Typically, Madole and his followers would commandeer a busy sidewalk corner in a White neighbourhood of New York City, gather a crowd, and begin speaking. Some twenty-two rallies of this sort were held in 1953, for example. Madole pulled no punches in his speeches. A report to the FBI from this period from an informant describes him as ‘a vicious son-of-a-bitch’. New York’s huge Jewish community, as well as the FBI, became aware of and alarmed by, the NRP activities. Hostile and mocking publicity ensued, such as a major article in the New York Post, ‘The Man Who Wants to Be Fuehrer’.

Demands were soon made that the authorities ‘do something’ about Madole. The problem was that Madole, like the earlier German-American Bund, conducted his activities strictly within the letter of the law. One thing that the Federal government could do, however, was to ‘investigate’ the NRP. In 1954, the House Unamerican Activities Committee, under the leadership of Harold H. Velde (R-Illinois) launched an investigation of the NRP and other ‘hate groups’. Party members were interrogated and spied on. The Movement feared that the government was going to crack down on the NRP in a heavy-handed manner as it did a decade earlier with the Bund when dozens of Bund members were sent to prison. Many members dropped out of the NRP and others scattered to the four winds, some running as far as Mexico.

The government’s findings were released on December 17, 1954, in a grandiosely entitled Preliminary Report on Neo-Fascist and Hate Groups, often referred to as The Velde Report for short. It was a scant 32-pages in length, half of which were devoted to the NRP. HUAC concluded that while the NRP was ‘Unamerican’ it did not pose an immediate threat to the American republic.

The Feds estimated that there were 200 NRP members. After the release of the report, there were far fewer. Only a tiny handful of activists remained. But Madole soldiered on. On one occasion, two or three party members climbed to the roof of a Manhattan skyscraper and showered thousands of leaflets onto the sidewalk below during a busy rush hour. But although Madole continued the party until his death, the effectiveness of the NRP as a vehicle for promoting National Socialism, or ‘Racial Nationalism’ as Madole preferred to call it, was over.

New York City was the centre of American National Socialism and Christian Nationalism before the Second World War. Consequently, it made some sense to try to exploit whatever residual support remained there in the late 1940s. But a decade later, New York was enemy territory. An insane Jew took Madole hostage in February 1958, with the intent of killing him, but Madole escaped unharmed. His remaining followers told him that he needed to relocate both the party and himself to a Whiter area, but Madole stubbornly remained in New York until the end.

United White Party / National States Rights Party

Mention was made earlier of Edward Fields, a high school student affiliated with the short-lived Columbians. After the demise of the Columbians, Fields continued his participation in the shadowy world of the post-War movement. In the early 1950s he journeyed to New York City, to check out the NRP. He was impressed by Madole’s intellect and dedication but put off by Madole’s ideological radicalism. He did not like Madole’s embrace of (non-Marxist) socialism, nor did he accept The New Yorker’s analysis that the USSR was no longer under strict Jewish control. Field’s also had a poor impression of many of the NRP’s activists, some of whom had marginal personalities and lifestyles.

Fields was not a National Socialist, but his belief system ran parallel to it, especially on racial issues. His goal was to create a racial movement that combined the ideology of the Columbians with a base of mass support among racially conscious Whites, who at that time were the majority of the White population.

In 1957, Fields was instrumental in convening a gathering of White racialists in Knoxville, Tennessee, to unite various small groups together into a single large party. Among those attending the gathering were Emory Burke, J.B. Stoner, Wallace Allen and John Kasper. Also present was 22-year-old Matt Koehl, who attended as a protégé of the controversial movement personality DeWest Hooker, who was unable to attend.

The immediate outcome of the convention was the formation of the United White Party, which was reorganized the following year as the National States Rights Party. It would remain the largest White racialist formation in the US for the next two decades.

Anti-Jewish attorney J.B. Stoner was the public face of the party, while Fields ran its day-to-day operations, and edited its monthly tabloid newspaper, The Thunderbolt. The publication took its name from that of the newsletter put out by the Columbians in 1946. The NSRP also adopted the flag and the thunderbolt insignia of the Columbians. Indeed, it can be said that the party was an extension or version of the earlier group. There were close ties between the NSRP and the Klan movement, although the NSRP pursued a strictly political agenda and the Klan operated in other arenas. The membership of the party and the KKK overlapped, and, with some accuracy, the NSRP was often referred to as the political wing of the Klan movement.

Although it was not a NS formation, the party had many National Socialists among its ranks. To keep these members from drifting away, Fields would confide to them that the NSRP’s initials secretly stood for ‘National Socialist Revolutionary Party’. This, and similar practices, later got Fields condemned as a ‘sneaky Nazi’. But Fields had good reason to be concerned about losing his NS members because an open, forthright National Socialist leader was only months away from raising the Swastika banner for the first time since 1945.

The advent of George Lincoln Rockwell

One participant in the Knoxville conclave who did not go on to join the UWP was a 39-year-old naval commander, who introduced himself to the gathering as ‘George Lincoln’. He gave a presentation to the convention outlining a plan to relocate the Black population of the US to Africa. He called it the ‘Lincoln Plan’.

George Lincoln Rockwell had abandoned his philosophy major at Brown University in 1941 because he, like many other Americans, could sense that war was on the horizon. As a patriotic American, he felt that it was his duty to defend his country in times of war. Beyond that, he believed that he had a moral obligation to help ‘stop Hitler’ from ‘conquering the world’. He joined the navy as an ordinary seaman; by the end of the conflict, he had risen to the rank of lieutenant commander. After the War, he became a member of the Naval Reserve. Rockwell was called back to active duty during the Korean War. He was eventually promoted to full commander.

Lincoln Rockwell was one of any number of former servicemen who came home to an America they did not recognize. Softness in the face of Communist aggression abroad, cultural Marxism at home, feminism, and what was euphemistically termed ‘civil rights’ were features of post-War America. But most of these men merely grumbled and got on with their lives. Rockwell, being more sensitive and reflective than his compatriots, began to investigate what had gone wrong. This was not the America that Rockwell and the others had fought for – and for which 500,000 Americans had died.

While stationed in San Diego during the Korean War, he became involved in the movement to draft Gen. Douglas MacArthur as the 1952 Republican presidential candidate. Through his contacts in the conservative wing of the Republican party, he was exposed to his first anti-Semitic literature. He did not take it seriously. But over time, he noticed that the charges made in anti-Jewish publications were, by and large, factually correct. Specifically, he was horrified to learn that the Jews were behind the communist movement both, at home and abroad.

In his political autobiography, This Time the World (1962), he wrote of this time:

I wondered about Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. I had learned that he was right about the Jews. It might be worth reading his book to see if he had anything else right, too.

I hunted around the San Diego bookshops and finally found a copy of Mein Kampf hidden away in the rear. I bought it, took it home, and sat down to read.

And that was the end of Lincoln Rockwell, the ‘nice guy’ – the ‘dumb goy’ – and the beginning of an entirely different person.

That was probably sometime in 1952. Rockwell was instantly converted to National Socialism. He spent the next seven years trying to find a workable strategy to promote National Socialism in a quiet, low-key way through the extreme right-wing of the Republican party. All of these efforts came to nought. Although there was plenty of awareness of the Jewish Question and racial issues in right-wing circles, there was no will or courage to tackle these problems effectively.

Rockwell realized that the Republicans were not the solution to the problems to which he had been awakened. But he was also unimpressed with the little NS or racialist groups that he investigated. It gradually dawned on him that if he could not work through any of the existing formations, he would have to start one himself.

By 1958 he had made the acquaintance of Harold Arrowsmith, an eccentric, anti-Jewish multi-millionaire (a billionaire in today’s terms). After some negotiation, they agreed: Arrowsmith would finance the new movement, and Rockwell would run its operations. Rockwell had his idea for a name for the group, but Arrowsmith insisted on the ‘National Committee to Free America from Jewish Domination’. A house in Arlington, Virginia, was rented for use as a headquarters, and a printing press was installed in its basement.

One of Rockwell’s strengths was that he thought in grand terms: thinking big is the key to big results. As the inaugural manifestation of the Committee, Rockwell planned for several nationwide anti-Jewish demonstrations to take place simultaneously. Rockwell himself would lead a picket of the White House, while Fields would hold demonstrations at the same moment in Knoxville and Atlanta. Rockwell hoped that James Madole would come aboard in New York City, while DeWest Hooker would lead an activity in Boston. Rockwell further wanted other demonstrations in Chicago, San Diego and elsewhere.

In the event, Rockwell went ahead in Washington and Fields in Knoxville and Atlanta, but the others fell through.

Still, it was an auspicious beginning – but soon everything collapsed. A suspicious bombing of a synagogue in Atlanta that was undergoing renovation led to the arrest of the Atlanta demonstrators. Arrowsmith was picked up by the FBI and interrogated for hours as though he were a common thief, all his wealth notwithstanding. The Arlington headquarters, which was also the home of Rockwell and his family, came under repeated attack and he sent his wife and children to safety in Iceland.

Finally, Arrowsmith withdrew his support and ordered Rockwell to vacate the house and return the printing press. Rockwell fought back and won a delay: at the beginning, he had insisted that Arrowsmith sign a contract, and it held up in court. But the victory was only temporary. The year 1958 came to a bleak end for Rockwell: he had put himself in a position where he could not turn back, and he could not see a way forward.

On March 8, 1959, Rockwell received a package sent to him by James K. Warner, a young admirer. In it was a large, Third Reich-era Swastika banner. A tingling ran up Rockwell’s spine: He suddenly saw the way forward.