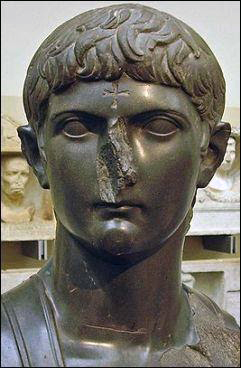

Bosch, The Last Judgement

(detail) 1500-05

Editor’s note: Regarding the view of Robert Morgan in the previous post, I disagree in the sense that it is unclear what would have happened to technology if the Third Reich had emerged triumphant. As the bad guys won the war, the use of technology in the West is self-destructing for the fair race.

It is true what Arthur Kemp says: that the use of non-whites after the Aryan conquests has been the primary cause of the decline of empires, due to the eventual miscegenation. But we live in a time when whites have become passionately ethno-suicidal, and that can only be explained by the texts linked in the sticky post. The history of Christianity, one of the two DNA axes of Aryan suicide according to the POV of this site, should be analysed with the same eagerness as white nationalists analyse the Jewish question.

When I talk to the white people, say, with whom I have spoken in England, I see an injured self-image to the degree that it evokes the mass psychosis, in a sector of the population, right after the triumph of Constantine. I refer to the Christian hermits and ascetics whose movement would eventually evolve into monastic orders. The mass psychosis, so well depicted by Hieronymus Bosch, had to do with the introduction of a fear that did not exist in the Greco-Roman world. I refer to the fear of eternal torment: something that, occasionally, persists even on the internet sites of southern nationalists in the US.

To understand what is happening to the white man it is necessary to realise that Kevin MacDonald and his followers fail to diagnose the origin of this tremendous collective guilt. Jews only thrive because of it. That’s why it is essential to tell what really happened to the Aryan psyche after the crushing triumph of Constantine. In chapter 14 of The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World, Catherine Nixey wrote:

______ 卐 ______

If you had travelled to the great cities in the eastern empire, to Alexandria and to Antioch, in the fourth and fifth centuries, then long before you came to a city itself you would have seen them. At dawn, they emerged from caves in the hills and holes in the ground, their dark robes flapping; their faces gaunt and pale from hunger, their eyes hollow from lack of sleep. As the cocks began to crow, while the city beyond was still slumbering, they gathered in the monasteries and hills beyond and, ‘forming themselves into a holy choir, they stand, and lifting up their hands all at once sing the sacred hymns’. An impressive sight – and an eerie one, their filthy, emaciated figures a living rebuke to the opulence and bustle of urban life below: a new, and newly strange, power in the world.

This was the great age of the monk. Ever since Antony had set out to the desert to do battle with demons, men had flocked after him in imitation. These men were the ideal Christians; the perfect renouncers of all those sinful pleasures of the flesh. And their way of life was thriving: so many had gone out since Antony that the desert was described as a city. And what a strange city this was. You wouldn’t find bathhouses and banquets and theatres here. The habits of these men were infamously ascetic. In Syria, St Simeon Stylites (‘of the pillar’) stood on a stone column for decades, until his feet burst open from the continual pressure. Other monks lived in caves, or holes, or hollows or shacks. In the eighteenth century, a traveller to Egypt had looked up into the cliffs above the Nile and seen thousands of cells in the rock above. It was in these burrows, he realized, that monks had lived out lives of unimaginable austerity, surviving on almost no food and only able to drink by letting down buckets on ropes to draw water from the river when it was in flood.

What was a monk at this time? In the fourth and fifth centuries, the now-ancient tradition of monasticism was only in its infancy and its ways were still being formed. In this odd and as yet uncodified existence, monks turned to the wisdom of their famous predecessors to know how to live. Collections of monkish sayings proliferated. Self-help guides of a sort – but a world away from Ovid. What is a monk? ‘He is a monk,’ wrote one, ‘who does violence to himself in everything.’ A monk was toil, said another. All toil. How should a monk live? ‘Eat straw, wear straw, sleep on straw,’ advised another revered saying. ‘Despise everything.’ Athletes of austerity, these men mortified their flesh in a hundred ways on a thousand days. One monk, it was said, had stood upright in thorn bushes for a fortnight. Another lived with a stone in his mouth for three years, to teach himself to be silent. Some, nostalgic for the tortures of past persecutions, draped themselves in chains and clanked round in them for years…

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that many of the empire’s urban, urbane men found this new breed of men who shunned the civilized life baffling to the point of repellent. To the Greek orator Libanius, monks were madmen, ‘that crew who pack themselves tight into the caves’ and who then ‘claim to converse with the creator of the universe in the mountains’. Their fasts were fiction, he said. These men weren’t starving themselves: they didn’t not eat; they just didn’t grow or buy their own food. When no one was looking, he said, they scuttled into the temples of the loathed pagans, stole those sinful sacrifices and ate them instead. Far from being ascetics they were ‘models of sobriety, only as far as their dress is concerned’. Their vicious and thuggish attacks on the temples weren’t done out of piety, said Libanius. They committed them out of pure greed…

The modern mind would tend towards a more clinical (albeit anachronistic) conclusion: many of these men must have been profoundly depressed.

Starvation was one of the most popular of monkish mortifications – no special equipment was required – but it was also one of the hardest to bear. One monk fasted all day then ate only two hard biscuits. Another lived from the age of twenty-seven to thirty on just roots and wild herbs, then for the next four years on half a pound of barley bread a day and some herbs. Eventually he felt his eyes going dim while his skin became ‘as rough as a pumice stone’. He added a little oil to his diet, then went on as before until he was sixty, to the awe and admiration of his fellow monks. There had been asceticism before – but this went further. Others, like ruminants, lived on all fours, browsing for their food like animals. In some ways hunger helped: a famished monk would be less beset by the demons of fornication or anger than one with a full belly. ‘A needy body,’ as one put it, ‘is a tame horse.’ But thoughts of food became an obsession with these men. In their reading of the Fall, the apple that Eve gives to Adam is not seen as a symbolic representation of sex; it is seen as nothing more, or less, than an apple. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs made monkish flesh.

The monks tormented themselves by what they put on their bodies as much as what they put in them. Some chose to dress in woven palm fronds instead of any softer fabric. To wear the usual coarse monkish habit was regarded, in this extreme world, as being ‘foppishly dressed’. Others, under the desert sun, tortured their skin with abrasive hair shirts. Another dressed in an extraordinary leather costume (that would in a later era have different connotations) that left only his mouth and nose exposed. To be pleasing to the Lord, a monk’s clothes must, it was said, be an offence against aestheticism: a habit should be tatty rather than smart, old rather than new, mended and re-mended and mended again. Anything less was vanity. A monk’s clothes should be such that, if he threw his habit out of his cell for three days, no one would steal it. The monks’ self-sacrifice was unquestionable; their smell must have been unspeakable.

If this sounds like a life lived on the edge of sanity, it was. In the searing heat of the desert day, reality shimmered, flickered and thinned. One monk saw a dragon in a lake; another slew a basilisk. Another saw the Devil himself sitting at his window. Demons appeared then vanished like smoke; meditating monks turned into flames. Watch one monk as he prayed and you would see his fingers turn into lamps of fire. Pray well and you might yourself become all flame. Demons teemed around monks like flies around food. One monk was beset by visions of rotting corpses, bursting open as they decayed. Alone for weeks, months on end in their cells, with nothing more than ageing hard bread to eat and an oil lamp to look at, monks were plagued by more tempting visions of sex, and food, and youth. Some monks lost their minds – if they had ever been in full possession of them. When Apollo of Scetis, a shepherd who later became a monk, spotted a pregnant woman in a field, he said to himself: ‘I should like to see how the child lies in her womb.’ He ripped the woman open and saw the foetus. The child and the mother died.

The reasons for these peculiar practices are hard to fathom. One theory is that Christian domination of the empire had brought many gains; but one of its great losses was that it had become considerably harder to be made a martyr by unsympathetic Roman governors. Deprived of the chance to die in one terrible, glorious, sin-erasing show, these men instead martyred themselves slowly, agonizingly, tormenting their flesh a little more every hour, thwarting their desires a little more every year. These practices would become known as ‘white martyrdom’. The monks died daily in the hope that, one day, after they died, they might live. ‘Remember the day of your death,’ advised one monk. ‘Remember also what happens in hell and think about the state of the souls down there, their painful silence, their most bitter groanings, their fear, their strife, their waiting…’ A terrible enough plight, but the monk had not finished yet; he concluded his cheering list with: ‘the punishments, the eternal fire, worms that rest not, the darkness, gnashing of teeth, fear and supplications…’

Carpe diem, Horace had said. Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you will be dead for eternity. The monks offered an alternative to this view: die today and you might live for eternity. This was a life lived in terror of its end. ‘Always keep your death in mind,’ was a common piece of advice: do not forget the eternal judgement. When one brother started to laugh during a meal, he was immediately reproached by a fellow monk: ‘What does this brother have in his heart, that he should laugh, when he ought to weep?’ How should one live well in this new and austere world? By constantly accusing yourself, said another monk, by ‘constantly reproaching myself to myself.’ Sit in your cell all day, advised another, weeping for your sins.

A hint of desert isolationism started to find its way into pious city life, too. In John Chrysostom’s writings, contact with women of all kinds was something to be feared and, if possible, avoided altogether. ‘If we meet a woman in the market-place,’ Chrysostom told his congregation, herding his listeners into complicity with that first-person plural, then we are ‘disturbed’. Desire was dangerously easy to inflame. Women who inflamed it were not to be relished as Ovid had relished them, but eschewed, scorned and denigrated in writings that made it abundantly clear that the fault of the man’s desire lay with them. In this atmosphere a group of fashionable women with their low-cut necklines were not praised as beauties but excoriated as a ‘parade of whores’.

Eventually, clerical disapproval was reinforced by law. Pagan festivals, with their exuberant merriment and dancing, were banned… If anyone declared themselves an official in charge of pagan festivals then, the law said, they would be executed. John Chrysostom jubilantly observed their decline. ‘The tradition of the forefathers has been destroyed, the deep rooted custom has been torn out, the tyranny of joy [and] the accursed festivals have been obliterated just like smoke.’