Lebenskraft ! (3)

Prague

25 and 26 April

On this trip, Prague in the Czech Republic was the first city whose beauty struck me.

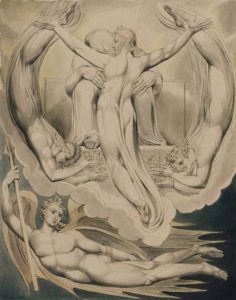

I arrived at night and saw the thirty statues on the Charles Bridge. Even in the freezing winter there are people on this famous bridge! All the statues, without exception, are either of the so-called ‘holy family’ or of Catholic ‘saints’. That night I photographed only one:

Very artistic indeed, but it is degenerate art because it is Christian propaganda. In fact, what I said about destroying the rebuilt Lutheran cathedral in Dresden applies also to Catholic art in Prague. All that will have to be destroyed by Kalki (see for example pages 132-140 in On Exterminationism which Savitri Devi wrote in 1956).

Taking such drastic measures is noticeable even in the new pope, a Chicago-born mongrel. Dedicated to the order of St Augustine, before he was Leo XIV he had criticised Trump’s anti-immigration policies. Or do Catholic racialists think it has nothing to do with their religion that the hotel I stayed at in Prague had blacks in the lobby? Are they so dishonest as to claim that it doesn’t affect the Czech collective unconscious to see their pope kissing the feet of a black migrant? Francis I wasn’t hypnotised by Jews: he was inspired by Francis of Assisi, who kissed lepers. I have said it a thousand times and it bears repeating: white nationalists are profoundly dishonest people, intellectual cowards who do not want to see what is right under their noses.

In the light of the next day I walked around the Old Square and saw the great church of ‘Our Lady of Tyn’, and then went to the Astronomical Clock that has been in operation since 1410, whose main attraction is the animated figures of the twelve apostles that come out at noon—twelve ethnic Jews! Then I visited Prague Castle, a citadel containing St Vitus Cathedral, St George’s Basilica and the Golden Alley. I had to buy a notebook because my notes began to pile up from what I was writing on loose papers during the trip.

I never imagined that a purely sightseeing trip would be riddled with devastating observations and anecdotes about the lobotomised eunuchs—the male Europeans of whom I have already spoken on this site, including the Czechs. I say eunuchs because there are now a lot of sandniggers inhabiting the Czech Republic.

In the centre of the old part of town I saw a strange sculpture, The Butterfly, dedicated to the two Czech ‘heroes’ who murdered Heydrich.

It seems obvious to me that in addition to tearing down all the statues, churches and religious monuments in Prague, a Temple in honour to Heydrich should be put in their place where Aryan culture is taught.

We don’t need a new religion like the Abrahamic ones, only to be aware of our pre-Christian cultures: a project that had already started in Himmler’s mystical castles. We must reclaim those cultures to educate our children according to the varied heritage represented by the Edda, the Mabinogion, Homer and Virgil. We must draw from that rich heritage, and the moral maxims of a good Roman like Cicero. We also need temples, and enclosures for reconnection with the heroes of National Socialism. A perennial fire in these spaces will be most inspiring! We need places where we can gather and remember the story of the white race told by William Pierce, and the after-dinner talks of Uncle Adolf. Remember: it’s all about the story we are telling us!

Back to my visit to old Prague. I visited again the Astronomical Clock but couldn’t enter the cathedral because just that day a mass was being celebrated for the funeral of Pope Francis I, and it was crowded. In Prague’s famous Jewish Quarter I saw the largest synagogue in medieval Europe, dating from 1270, and passed the rabbi’s house in the most expensive part of the city. The sculptures on Charles Bridge that I had seen at night I was able to see in full daylight and photographed them (in this series I only reproduce a small fraction of the photos I took).

When among the myriad of tourists I saw a good-looking Aryan with a pram and his gook wife, I wrote down that he was just the sort of people to be executed—Aryan male, mongrel child and wife—during what Pierce called ‘The Day of the Rope’. Also at the entrance to the Castle there was an army of tourists, and there I saw another pure Aryan with his Indian wife, carrying a half-breed baby: what I have been calling the sin against the holy spirit of life.

Here is my shock therapy to cure Europeans of such ethnosuicidal barbarities. It took the Czechs six hundred years to build Prague Cathedral. Kalki would destroy it in a single second with a few-kiloton atomic bomb, like the one used at Nagasaki. When the time came that I took out this foto—:

—I thought: ‘This must have remained part of the Third Reich. Hitler was right to take over Czechoslovakia’. Inside the castle I saw an oil painting of the idiot Joseph II of Habsburg, Marie Antoinette’s brother, who emancipated the Jews not because of kike propaganda but because he was a good Christian (Jewry hadn’t yet taken over the media).

Then I went downstairs and saw the Archbishop’s Palace with black flags for the death of the pope who, literally, kissed the feet of the invading niggers. The archbishop lives in that building.

What bothered me the most was something that happened at 3:15 pm.

In the middle of the crowd, a gook kissed his girlfriend: an Aryan nymph, the kind that even the SS would boast about in their propaganda booklets. This happened on the most popular square in the old part of Prague. In a truly civilised world, this would merit the death penalty for the gook, and the gift of that spoiled brat to a good Aryan soldier for his military services. What is the point of so much architectural, pictorial and sculptural beauty if the race that created it is now perpetrating ethnic suicide?

According to the white nationalist myth, the Jews hypnotised the Gentiles with their media and academic propaganda, supported by their financial power. In reality, I thought among the throng of tourists, it is the people who are screwed. The elites just take advantage of these masses which reminds me of the experiment of putting electrodes on rats’ brains pleasure centre. The animals push a button, like neurologically masturbating, to such a degree that they forget to even eat.

Similarly, all these tourists are degenerated by pleasure. In my notebook I wrote: ‘It is the Aryan people, along with the elites of course, that must be punished with the fury of Kalki: a Himmler to the nth power’.