Criminal History, 193

For the context of these translations click here.

PDFs of entries 1-183 (several of Karlheinz Deschner’s

books abridged into two) can be read here and here.

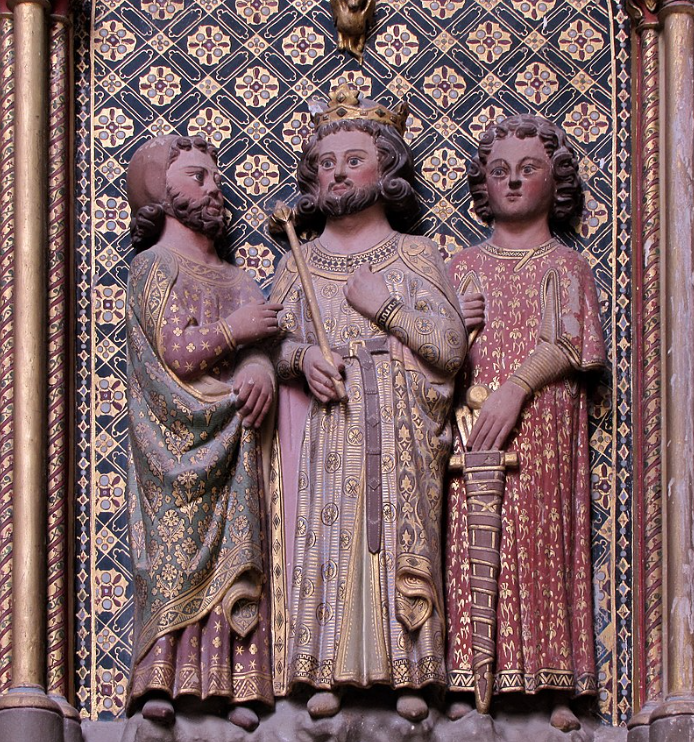

Charles the Fat in a 14th century relief, flanked by a squire and a knight.

25 years of Joseph’s marriage – the acid test passed

Like their first husband (or their second?), the high couple did not want to let the adultery sit on them. After only a few days, Charles, therefore, brought his wife Richardis ‘before the Imperial Assembly on the same matter and’, writes Abbot Regino with delight, ‘it sounds marvellous that she publicly confesses that he has never mingled with her in a carnal embrace, although they have been in his company for more than ten years through a lawful marriage’.

More than ten years? Twenty-five years. Because Karl the Fat had already married the daughter of the Alsatian and Breisgau count Erchanger in 862, a quarter of a century of Joseph’s marriage. No, much more beautiful, even purer: ‘She even claims that she has remained free not only of his, but of all male concomitance (omni virili commixtione). She praises the integrity of her courage and confidently offers to prove this, if it pleases her husband, by the judgement of Almighty God, either through a single battle or through the test of the glowing ploughshares; for she was a godly woman.’ This is why, after the divorce, Empress Richardis withdrew to the Andlau monastery in Alsace, which she had built on her estates, no longer for the sake of any men but, says Abbot Regino, ‘to serve God’.

The emperor generously refrained from proving their unimpaired might through judicial duels or glowing ploughshares.

Church propaganda, however, took up the miraculous case of chastity and, with fantastic embellishments, had the empress gloriously pass the fiery ordeal. The Martyrology of Germania (with the imprimatur of 6 May 1939) still holds fast to such a ‘passed trial by fire’. For centuries, a wax shirt was also presented in the Etival monastery which, when ignited at all four ends on the naked body of the tested person, neither destroyed the virgin body of the majesty nor was it damaged. And while the perpetrator atones for the filthy lie on the gallows, poor Richardis (who was not entirely poor; she had already been given several women’s convents at the end of the 70s) distributes ‘everything she still had to the poor and convents’.

And she also went into the convent, living only for the salvation of her soul, humility and prayer; which is why God glorified her tomb through miracles and finally, in 1049, Pope Leo IX elevated her holy body, which was ‘tantamount to canonisation’, writes in his Legend of the Saints the Capuchin priest Wilhelm Auer of Reisbach, ‘with the approval of the Most Reverend Bishop´s Ordinary of Augsburg and the permission of the superiors’. Immediately afterwards, he gives us the Church Prayer: ‘O God, who has freed your Blessed Virgin Richardis from the slander of men and crowned her with eternal glory: we ask you to grant us that we may love our neighbour in word and deed according to her example and through her intercession, so that we may attain the rewards of eternal love. Amen.’

Well said, in passing, to love our neighbour in word and deed according to their example… One must not think of poor Charles the Fat. After twenty-five years of Joseph’s marriage to a saint he is not even beatified! Of course, according to Capuchin priest Wilhelm Auer von Reisbach: ‘He had become weaker and weaker in spirit… and now rejected the noblewoman, even though she declared herself ready for all tests of her innocence and purity.’

Priests don’t know what to do with someone like Charles the Fat, who loses his nerve at every outrage. And historians not much more. Both idolise gentlemen of a completely different ilk, men with a punch above all, yes, with a punch, men of the criminal calibre of Charlemagne I for example; bandits of the state, devourers of nations, scourges of humanity, great leaders who razed hundreds of thousands of square kilometres to the ground and walked over corpses like cannibals of secular stature or world-historical terrorists. This is called Carolingian universal politics, while Charles III the Fat always ‘fails again’ (Handbuch der Europäischen Geschichte), and historians generally abhor nothing as much as weakness and failure, and love nothing as much as strength and success, regardless of the price.