But this new world, inspired by eternal principles, this environment generating demigods of flesh and blood, had to be forged from the already existing human material and the conditions, both economic and psychological, in which it found itself. These conditions evolved in the years before and after the seizure of power, especially during the war years. This must be taken into account if we want to understand both the history of the National Socialist regime and the feature that the Third German Reich had in common with all the highly industrialised societies of the modern era, namely the emphasis it placed on the application of science and material prosperity within everyone’s reach, presented as an immediate goal to millions of people.

We must never forget that ‘it was out of the despair of the German nation that National Socialism emerged’.[1] We must never lose sight of the picture Germany presented in the aftermath of the First World War: the economic collapse following the military disaster; the wanton humiliation of Europe’s most vigorous people, their sense of betrayal, the insistence of the Allied commissions on reparations under the terms of the infamous Treaty of Versailles; the growing threat, and then tragic reality, of inflation, unemployment, hunger and the Jewish usurer replying to the German mother who had come to sell her wedding ring for an already paltry sum: ‘Keep it! You’ll come back next week and give it to me for half that price!’ But…

‘The cloud is already less dark where the dawn shines

And the sea is less high and the windless rough’.[2]

He who, ‘from age to age’ takes human form and returns ‘when Justice is trampled, when evil triumphs’ and restores order for a time, was watching, incognito, lost in the crowd of the desperate. He rose; he spoke as Siegfried once spoke to the Valkyrie; as Frederick Barbarossa, emerging from his mysterious cave, must one day speak to his people. And prostrate Germany felt the divine breath pass over her. And she heard the irresistible Voice: the same; the eternal.

And the Voice said: ‘It is not the lost wars that ruin peoples. Nothing can ruin them, except the loss of that power of resistance which lies in the purity of blood’.[3]

And the Voice said: ‘It is not the lost wars that ruin peoples. Nothing can ruin them, except the loss of that power of resistance which lies in the purity of blood’.[3]

She said: ‘Deutschland erwache!’, ‘Germany wake up!’ And the haggard faces, and the weary faces—the faces of men who had done their duty and yet lost everything; of those who were hungry for bread and hungry for justice—arose; the dull eyes met the glowing gaze of the living Unknown Soldier, a simple corporal in the German army who had like them ‘made war’.

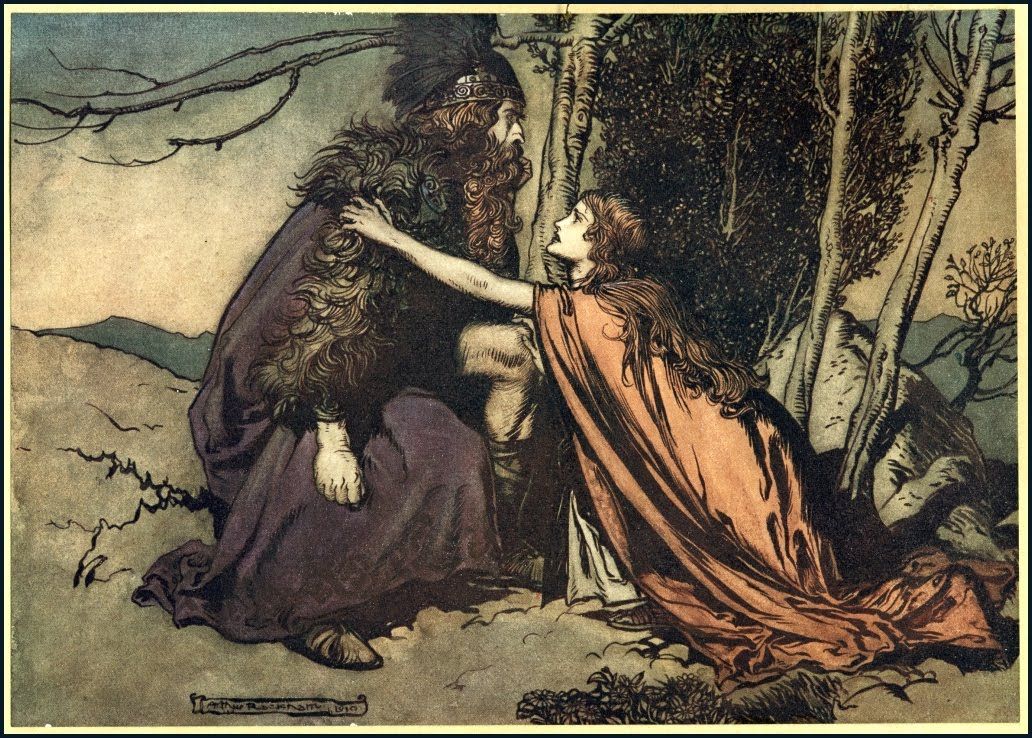

And they saw in him the immortal gaze of the red-bearded Frederick, whose return Germany awaits; of the One who has returned a hundred times over the centuries, in various places under various names, and whose return the whole world awaits. From the depths of the dust Germany has cried out its allegiance to him. Galvanised, transfigured, she rose and followed him. She gave herself to him in the fervour of her reconquered youth—to him in whom her atavistic intuition had recognised the Depositary of the Total Truth. She gave herself to him like the Valkyrie to Siegfried, conqueror of the Dragon, master of Fire.

‘Nowhere in the world is there such a fanatical love of millions of men for one’ [4] wrote Dr Otto Dietrich in a book about the Führer at the time. It was this love, the unconditional love of the little people—of the unemployed factory workers and craftsmen, the ruined shopkeepers, the dispossessed peasants, the unemployed clerks, all the good people of Germany and of a minority of inspired idealists—who brought to supreme power the God of all time back in the form of the eloquent veteran of the previous war. They recognised him by the magic of his words, by the radiance of his face, by the power of his every gesture. But it was his fidelity to the promises he made during the struggle for power that bound them to him unwaveringly, even in the hellstorm of the Second World War and—more often than the superficial observer thinks—beyond the absolute disaster of 1945.

What had he promised them? Above all Arbeit und Brot, work and bread, Freiheit und Brot, freedom and bread; the abolition of the Versailles Diktat, that treaty imposed on Germany with a knife at her throat and claiming to seal forever her position as a defeated and dismembered nation: a place in the sun for the German people; the right, for them, to live in honour, order and prosperity thanks to the virtues with which Nature has endowed them; the right, finally, to recover in their bosom their blood brothers, torn from the common fatherland against their will. (In 1918 the Austrian Parliament had, as is too often forgotten, voted unanimously to join Germany.)

Politicians, especially those who come to power ‘by the legal and democratic means’ as Adolf Hitler did, rarely keep the promises they have made from the electoral podium, or on their propaganda posters and pamphlets. Sincere patriots do not necessarily keep their promises. They are sometimes overtaken by events. They make mistakes, even when they have not lied. Only the Gods do not lie or make mistakes. They alone are faithful, always. Adolf Hitler kept in full all the promises he had made to the German people before taking power. More than that: he went beyond what he had promised.

And if the very fate of the Age in which we live had not stood in the way of his momentum; if it had not been too late for a final turnaround against the tide of Time to be possible, and too early to hope, so quickly (and so cheaply) for the end of this temporal cycle and the dawn of the next one, he would have given much more, both to his people and to the whole world.

_______

[1] Free Remarks on War and Peace, p. 252.

[2] Leconte de Lisle, Les Erinnyes Part 2, iii.

[3] Mein Kampf, 1935 edition, p. 324.

[4] ‘Nirgends auf der Welt gibt es eine derart fanatische Liebe, von millionen Menschen zu einem….’