Flag was bored with the inactivity and wandered away. He was becoming bolder and was sometimes gone in the scrub for an hour or so. There was no holding him in the shed. He had learned to kick down the loose board walls. Ma Baxter expressed the belief, only because it was her hope, that the fawn was going wild and would eventually disappear. Jody was no longer even troubled by the remark.

Chechar’s note: But the fawn did something that he was not supposed to do.

Jody said, “He didn’t know what he was doin’.”

“I know, Jody, but the harm’s as bad to the ‘taters as if he done it for meanness. We got scarcely enough rations now to do the year.”

“Then I’ll not eat no ‘taters, and make it up.”

“Nobody wants you should do without ‘taters. You jest got to keep track o’ that scaper. If you keep him, it’s your place to see he don’t do no damage.”

“I couldn’t watch him and grind corn, all two.”

“Then keep him tied good in the shed when you cain’t watch him.”

“He hates that ol’ dark shed.”

“Then pen him.”

Jody rose before day the next morning and began work on a pen in the corner of the yard. He studied its position with an eye to using the fence for two corners of the pen, and to having it where he could see Flag from most of his own work-spots, the millstone, the wood-pile and the barn lot in particular. Flag would be content, he knew, if he was in sight of him. He finished the pen in the evening, when his chores were done. The next day he untied Flag from the shed and lifted him into the pen, kicking and struggling. Flag was over the bars and out and at his heels again before he reached the house. Penny found him again in tears.

Further ahead in the story:

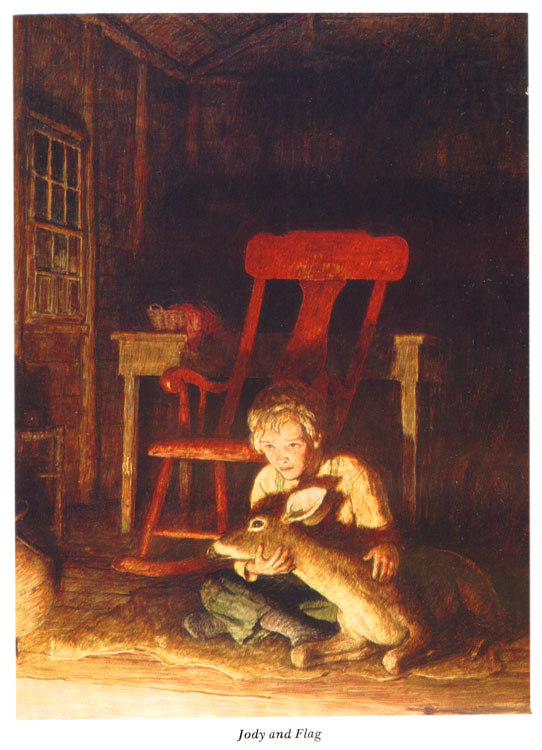

Jody rolled over on his side and stretched one arm across Flag. The fawn lay asleep, his legs tucked under his stomach, like a calf. His white tail twitched in his sleep. Ma Baxter did not mind his being in the house in the evening, after supper.

The wolves had invaded the lot and killed the heifer calf. A band of them, three dozen or more, milled about the enclosure. Their eyes caught the light in pairs, like corrupt pools of shining water.

“Now this be the kind o’ time a man needs a snort,” he said. “I shore aim to beg a quart offen the Forresters tomorrer.”

“You goin’ there tomorrer?”

“I got to have he’p. My dogs is all right, but a big woman and a leetle man and a yearlin’ boy is no match for that many hongry wolves huntin’ in a pack.”

And next morning…

Penny was back in time for dinner. He had eaten little breakfast and was hungry. He would not talk until he had eaten his fill. He lit his pipe and tilted back his chair. Ma Baxter washed the dishes and brushed out the floor with the palmetto sweep.

“All right,” Penny said, “I’ll tell you jest how it stand. Hit’s like I figgered, the wolves was about the worst destroyed by the plague of ary o’ the creeturs.”

“That’s it. I had me a good go-round with them jessies. We cain’t see it the same way about killin’ ’em. I want a couple o’ good hunts, and traps around our lot and their corral. But the Forresters is bent on pizenin’ ’em. Now I ain’t never pizened a creetur and I don’t aim to.”

Ma Baxter flung her dishcloth at the wall.

“Ezra Baxter, if your heart was to be cut out, hit’d not be meat. Hit’d be purely butter. You’re a plague-taked ninny, that’s what you be. Leave them wild things kill our stock cold-blooded, and us starve to death. But no, you’re too tender to give ’em a belly-ache.”

He sighed.

“Do seem foolish, don’t it? I jest cain’t he’p it. Anyways, innocent things is likely to git the pizen. Dogs and sich.”

“Better that, than the wolves clean us out.”

“Oh now Ory, they ain’t goin’ to clean us out. They ain’t like to bother Trixie nor Cæsar [the horse]. I mis-doubt could they git their teeth through their old hides. They shore ain’t goin’ to mess up with dogs that fights as good as mine. They ain’t goin’ to climb trees and ketch the chickens. They’s nary other thing here to bother, now the calf’s gone.”

“There’s Flag, Pa.”

It seemed to Jody that for once his father was wrong.

“Pizen’s no worse’n them tearin’ up the calf, Pa.”

“Tearin’ up the calf was nature. They was hongry. Pizen jest someway ain’t natural. Tain’t fair fightin’.”

Ma Baxter said, “Hit takes you to want to fight fair with a wolf, you–”

“Go ahead, Ory. Ease yourself and say it.”

“If I was to say it, hit’d take words I don’t scarcely know to think, let alone speak.”

“Then bust with it, wife. Pizenin’s a thing I jest won’t be a party to.”

He puffed on his pipe.

“If it’ll make you feel better,” he said, “the Forresters said worse’n you. I knowed they’d mock me in the head when I takened my stand, and they done so. And they’re fixin’ to go right ahead and set out the pizen.”

“I’m proud there’s men some’eres around.”

Jody glowered at both of them. His father was wrong, he thought, but his mother was unfair. Something in his father towered over the Forresters. The fact that this time the Forresters would not listen to him, must mean, not that he was not a man, but that he was mistaken. Perhaps, even, he was not wrong.

The passage shows that Jody’s father did have a higher degree of fairness and empathy toward the wild animals than his rude neighbors.

The Forrester poisoning killed thirty wolves in one week.

A fire was crackling on the kitchen hearth. His mother was placing a pan of biscuits in the Dutch oven. She had an old hunting coat of Penny’s over her long flannel nightgown. Her gray hair hung in braids over her shoulders. He went to her and smelled of her and rubbed his nose against her flannel breast. She felt big and warm and soft and he slipped his hands under the back of the coat to warm them. She tolerated him a moment, then pushed him away.

“I never had no hunter act like sich a baby,” she said. “You’ll be late for the meetin’ if breakfast’s late.”

Jody went with the adults to hunt those wolves that didn’t fall in the trap. The boy had to scare them by shooting and drive them towards the real hunters. Since he had done that alone, “Jody was white.”

Work was light and Jody spent long hours with Flag. The fawn was growing fast. His legs were long and spindling. Jody discovered one day that his light spots, the emblem of deer infancy, had disappeared. He examined the smooth hard head at once for signs of horns. Penny saw him at it and was obliged to laugh at him.

“You shore expect wonders, boy. He’ll be butt-headed ’til summer. He’ll not have no horns ’til he’s a yearlin’. Then they’ll be leetle ol’ spiky ones.”

Jody knew a content that filled him with a warm and lazy wonder. Even Oliver Hutto’s desertion and the Forresters’ withdrawal were distant ills that scarcely concerned him. Almost every day he took his gun and shot-bag and went to the woods with Flag. The black-jack oaks were no longer red but a rich brown. There was frost every morning. It made the scrub glitter like a forest full of Christmas trees. It reminded him that Christmas was not far away.