extermination, 6

Chapter 18

Strategic evolution

The ultimate makeover

Despite defensive adaptations like xenophobia, changes in sexuality, raising wolves as guard dogs, becoming more athletic, developing a trauma-proof CNS [Central Nervous System], keeping to their own territory (and away from forests), plus a plethora of defensive teems,[1] the fossil record reveals the Levantine population continued to decline. It seems that the Skhul-Qafzeh humans were slowly losing the battle for survival—and heading inexorably towards extinction. But at this pointy end of the predation cycle, things started to change, radically.

To understand what happened next, we need only examine the situation through the prism of Darwinian theory. This predicts the extraordinary and dramatic events that unfolded as the human population plunged towards extinction. For a start, it tells us that all the weak, slow-moving, dim-witted, gullible humans went the way of the dodo—their genes eradicated from the gene pool.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: This is what will happen to gullible Aryans: the fate of the Dodo!

______ 卐 ______

Then, as all but the most diehard survivors perished, it generated intense selection pressure for a new kind of adaptation. Why? Because the old defensive adaptations were no longer adaptive. Neanderthal predation was continuing to decimate the Skhul-Qafzeh population and make their lives a misery. What was needed was a radical new adaptation, one that didn’t just help humans evade or escape Neanderthals. To survive as a species and to be truly free of Neanderthals, humans needed to go on the offensive. This required a revolutionary new approach to the problem. And this is precisely what I theorise happened. The enormous selection pressure generated by Neanderthal predation gave birth to a completely new group of adaptations, which I call strategic adaptations.

Strategic adaptations are not defensive, they are offensive and, in the Levant, their blind objective was to empower the Skhul-Qafzeh humans to engage Neanderthals in combat and defeat them. Strategic adaptations were blindly aimed at the complete annihilation of the Eurasian Neanderthal. [Here and below, emphasis added by Ed.]

The emergence of strategic adaptations makes sound evolutionary sense. Defensive adaptations were useful, up to a point. But ultimately, the only way the Levantines could achieve continuity and security and be predation-free was to permanently remove Neanderthals as ecological competitors. Skhul-Qafzeh humans had to depose Neanderthals from the top of the food chain and take over the mantle of apex predator.

The enormity of the task was mind-blowing. For a timid prey species to turn the tables on the top predator on the planet would require the reversal of an ancient and well-established predator-prey interaction and would almost certainly have been

unprecedented in the animal kingdom. Humans had to evolve into a militaristic species, the likes of which had never been seen before. They would have to become more intelligent, ruthless, cunning, aggressive, cruel and determined than their lethal adversary—become a new super-warrior species with one specialist skill: to kill Neanderthals.

A superior killing machine

Skhul-Qafzeh humans born with offensive physical characteristics and aggressive teems—any kind of inheritable trait that allowed them to outcompete, kill, wound or chase off Neanderthals—lived to pass on their offensive genes along with their newly acquired Neanderthal battle teems. Strategic adaptations included any physical or behavioural adaptation that directly or indirectly contributed to Neanderthal extinction.

NP theory argues that, for the first time, a few humans didn’t run and hide when they saw Neanderthals approaching. Instead, they courageously stood their ground and engaged Neanderthals in combat. Bolstered by their newly-acquired strategic adaptations, the humans began to win a few victories. Initially, they would have lost a lot of men, but this only concentrated the strategic adaptations into a smaller group.

Because the human survivor population was so small at the time and the strategic adaptations were so adaptive, the genes that encoded the most aggressive adaptations spread to fixation very quickly. Soon, a new transitional human emerged. Natural selection was gradually evolving the ultimate killing machine—the most virulent hominid species by far—modern humans.

Once acquired, what humans did with these strategic adaptations is not in doubt. Charles Darwin, in The Descent of Man, provides a salutary reminder of what lay ahead for the Neanderthals:

We can see, that in the rudest state of society, the individuals who were the most sagacious, who invented and used the best weapons or traps, and who were best able to defend themselves, would rear the greatest number of offspring. The tribes, which included the largest number of men thus endowed, would increase in number and supplant other tribes.

The strategic adaptations which I propose played a pivotal role in humans gaining the upper hand over their historical enemy are a disparate lot. They include high intelligence, cruelty, male bonding and aggression, language capacity, the facility to interpret intention from behaviour, organisation, courage, guile, conjectural reasoning, a genocidal mindset, improved semantic memory, consciousness, competitiveness and the ability to form strategic coalitions, or proto-armies.

These adaptations included a raft of new aggressive them and us teems that unified the Levantine humans into a cohesive combative force (the first proto-army) that encouraged them not only to stand their ground but to attack Neanderthals and exterminate them without guilt or remorse.

A major plank of the hypothesis is that strategic adaptations emerged only towards the end of the period of Neanderthal predation (during the population bottleneck) sometime between 70,000 to 50,000 years ago. To prove the strategic adaptations hypothesis, it must be demonstrated that they all emerged because they helped humans kill Neanderthals, and that they all appeared between 70,000 and 50,000 years ago.

Because there are so many strategic adaptations it is not possible to make a detailed examination of them all in this book. Instead, my analysis is limited to a sample of the most important strategic adaptations:

- Male aggression

- Courage

- Self-sacrifice

- Tough-mindedness

- Machiavellian intelligence

- Language

- Creativity

- Organisation—the origins of human society

- Gender differences

- Division of labour.

Bloodlust teems

Courage, bravado and proactive aggression are normally anathema (or a last resort) to prey species. From a survivalist perspective, it makes more sense to be timorous and cautious. But, because killing Neanderthals would require hand-to-hand combat, getting into close contact required courage, audacity and even self-sacrifice. Gradually, timid defensive individuals lost out to a new breed of aggressive, courageous, tough-minded individuals.

It is not difficult to see how a ‘bloodlust teem’ could be encoded. If a group of Skhul-Qafzeh men came across a wounded or infirm Neanderthal, they might easily work themselves up into a highly agitated state and beat him to death before pounding his corpse to a pulp. This kind of frenzied excitement (observed so frequently among wild chimpanzees) could generate enough excitement in one individual to precipitate a directed (or teemic) mutation in an intron (the nonprotein-coding region of his DNA). If the affected intron happened to be on his Y (male sex) chromosome, the bloodlust emotions he experienced during the melee would be permanently encrypted into his ncDNA and subject to patrilineal descent. Once inherited by male descendents, the archived bloodlust emotions would remain unexpressed until triggered by the sight or sound of a Neanderthal. When expressed, the bloodlust emotions could precipitate the same kind of reckless and frenzied aggression.

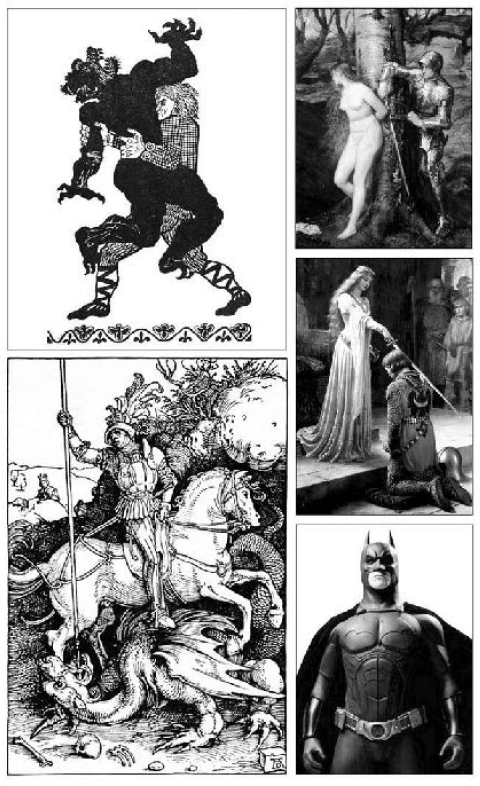

Only in this specific and atypical ecological context were reckless daring, proactive aggression and self-sacrifice adaptive behaviours. When it came to fighting Neanderthals, risk-taking become both a laudable human attribute and a functional adaptation. In this context, foolhardy machismo and reckless bravado became laudable heroism. American anthropologist Joseph Campbell once said, “A hero is someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself.” And, while the great cause was genocide, for those Skhul-Qafzeh humans it would have been a noble cause. Heroic males would not only be praised and appreciated as altruistic and self-sacrificing by the folk they defended, but would also be highly sought after as sexual partners by admiring females. Even today, research shows that when choosing a mate, women place significantly greater importance on altruistic traits than anything else.

Thus, the nascent genes for courage, altruism, self-sacrifice—indeed for heroism itself—dispersed through the community, transforming the Levantines from a timorous prey species into a proto-militaristic tribe.

The current anthropological model does not adequately explain the historic and cultural preoccupation with the hero’s struggle against the forces of evil. However, in the context of an adversarial struggle between two sibling species, it makes sound evolutionary sense.

It follows that the Skhul-Qafzeh attitude to killing also had to change. Early humans obviously killed other animals, but only for food. Now for the first time, they had to kill something they didn’t intend to eat, and another hominid to boot. And kill them without compunction, hesitation or guilt. This required a library of virulent new aggression teems.

These new teems were adaptable because, if early humans could not bring themselves to administer the coup de grâce to a wounded Neanderthal, then these soft-minded individuals risked retaliation, revenge and possibly their own lives. Selection favoured the cruel and the merciless. This was, after all, war before there was a notion of it—before civilisation, before even barbarism. There were no treaties, protocols, exchange of prisoners or rules of engagement. No field hospitals, no Red Cross and no POWs. In this context of quintessential savagery, mercy was not only maladaptive, it was not a practical option.

To dispatch Neanderthals efficiently and without pity, humans had to perceive them psychologically and emotionally in a new way. And this is where teems proved so functional. Teems can encode extreme antipathetic feelings into genetic sequences. Once encoded into ncDNA and inherited, Neanderthal hostility teems provided the emotions used to instinctively loath and dehumanise Neanderthals. They allowed the Levantines to perceive Neanderthals as sub-human, not even in the same category as animals. After all, the animals they regularly killed for food were not despised but were more likely revered for their speed, grace and life-force, and because they gave their lives so that humans could survive. This respect for prey (at times elevated to a spiritual relationship) is evident in every modern hunter-gatherer culture.

Neanderthals though, were a special case.

They were, in all probability, considered by humans as ‘worse than animals’, categorised metaphorically as pests, along with cockroaches, spiders and rats.

This would have served an important adaptive function. Seeing Neanderthals as subhuman allowed humans to slaughter them without guilt or remorse. Administering the coup de grâce to a wounded Neanderthal would be as easy as squashing a cockroach or crushing a rat with a rock.

The selection extended to favour men who were willing to give up their lives fighting Neanderthals. Under normal circumstances, male self-sacrifice would almost certainly be maladaptive, but in lethal combat with Neanderthals, this level of commitment and courage was obviously a strategic advantage that could turn the tide of a battle. Also, male bonding, pack mentality and obedience to the leadership would be eminently adaptive because discipline, organisation and hierarchy are essential elements of military success.

Within the context of the life and death struggle in the Levant between two adversarial sibling species, aggression, risk-taking, self-sacrifice, and the ability to exercise lethal violence without hesitancy (all derived from Neanderthal teems) were advantageous and essential to human survival.

Collectively, this disparate assortment of aggression traits in modern humans has been aptly described by psychologist Erich Fromm as ‘malignant aggression’, which he says is biologically nonadaptive. Considering that during the last century alone, 203 million people were slaughtered by other human beings, he’s got a point. But while malignant male aggression in today’s fully modern humans is unquestionably deleterious, back in the torrid days of Neanderthal predation, malignant male aggression was the lynch pin of Skhul-Qafzeh survival and renewal.

______ 卐 ______

Editor’s note: Note how Danny Vendramini—a normie, after all—fails to realise that, just as Neanderthals were the mortal enemies of our distant ancestors, Erich Fromm, a Jew who fled National Socialist Germany to take refuge in Mexico (the psychoanalyst who destroyed my life studied with Fromm) is the modern equivalent, along with other influential Jews, of the forgotten prehistoric crisis. From this angle, the final solution reached by our hominid ancestors is the same as the final solution devised by Heydrich at the Wannsee Conference. Today’s racialist conservatives do not want to see something so obvious because they have internalised, to the core of their souls, Judeo-Christian prohibitions.

Vendramini ends that section of the chapter with these words:

______ 卐 ______

The challenge to existing theories of human evolution is to explain how and why malignant aggression and its correlates—warfare, racism, and genocide—were initially selected, and what adaptive function they conferred. It is hard to imagine any situation, apart from Neanderthal predation, where such extreme levels of male aggression (levels that are still evident today) would be adaptive.

Footnote:

[1] Teems are inheritable packages of emotion, and provide only an emotional memory of a traumatic incident. Teems derived from Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons present only half the picture—and no details. They describe what the others felt like but not what they specifically looked like. To flesh out the details, Mesolithic and Neolithic humans had to use their imagination, or draw on their storytellers and mythographers (all aspects of culture) to give form to the demons, monsters and satanic creatures they believed lurked in the darkness beyond their walls. In other words, culture gives form to teems. Even today, when modern humans attempt to identify the source of residual anxieties, they too must draw on their imagination, just as their ancestors did, or project their feelings onto one of the monsters from mythology, literature or the movies.

______________

Editor’s note: See also Vendramini’s second book, The Second Evolution: The secret role of emotion in evolution.

3 replies on “Neanderthal”

“Neanderthal predation was continuing to decimate the Skhul-Qafzeh population and make their lives a misery.”

The problem with the lower thinking negros, latinos, and the rest, is they just cant think outside themselves. There’s an inability to think, to analyze at the systems level. An inability to escape their immediate emotional reactions and rationally compute. Another problem Europeans have is a form of anthropomorphic fallacy. They do not see these negros as alien life forms. They do not see them as a threat. They project and assume negros think like they do. All the supernatural nonsense, especially abrahamic religions, has only made matters worse. Add in jewish communist programming and European genocide is right around the corner (btw, Fromm’s Phd was Hebrew Law, not psychology. He came from a long line of rabbis). Look at the low white birth statistics. Look at the immigration rates from non-white countries into white countries, etc.

“Humans had to evolve into a militaristic species, the likes of which had never been seen before. ” True. All life forms have evolved in conflict, and controlled by sociobiological processes. The ancient Greeks had a saying that war is the father and king of us all. The writer Frank Herbert sums it best: “war has its roots in the single cell of the primordial seas. Eat what you touch or it eats you.” The jews have taken this awareness from us, allowing these negro neanderthals in to destroy us.

“What was needed was a radical new adaptation.” This is why the jews have pulled out all the stops against national socialism (they actually practice themselves). Basically, we have to move past analysis into action. WE need all efforts for a new political party now. We are past the tipping point. I express this everywhere and get attacked. I take this as a good sign.

Dr Skrbina posted an article of eugenics yesterday over at unz you should read. Thx for your work CT.

True, but it must be added that this didn’t happen until the white man adopted the religion of St. Paul for our consumption: “There is neither Jew nor Greek… for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Wondering if we’re being deceived or perhaps ignorant about the actual appearance of Neanderthals. Shouldn’t looking at Neanderthal reconstructions evoke some form of visceral emotion in humans?

Entertaining the idea that some Neanderthal is still present in modern populations (perhaps a specific people, as some suggest). What if – in response to humans winning the upper hand – Neanderthals adapted to a more subtle kind of warfare? I.e. mimicking human appearance, infiltration, deception, etc.

Tying both paragraphs together, which modern humanoid appearance triggers the most visceral reaction in humans? Perhaps a specific color, physiognomy? In any case, mainstream science probably doesn’t back up any theories like that based on DNA research.