‘The great masses of the people will more easily fall victims to a big lie than to a small one’.

—Adolf Hitler

‘The great masses of the people will more easily fall victims to a big lie than to a small one’.

—Adolf Hitler

The communism of antiquity, 6

by Alain de Benoist

This certainty that the Empire needed to collapse for the Kingdom to come explains the mixed feelings of the early Christians towards the barbarians. Undoubtedly, at first, they felt as threatened as the Romans.

Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, distinguished between external enemies (hostes extranei) and internal enemies (hostes domestici). For him, it was the Goths that Ezekiel was referring to when he spoke of the people of Magog. But, in the second stage, these barbarians, who were soon to be evangelised, became auxiliaries of divine justice. Christians could not admit that their fate was linked to that of a ‘Babylon of impudence’. That is why the Carmen de Providentia or the Commonitorium of Orentius are scarcely interested in other than the ‘enemies within.’ In the 3rd century, in his Carmen apologeticum, a Christian author, Comodian, speaks of the Germans (more precisely of the Goths) as ‘executors of God´s designs.’ In the following century, Orosius, in turn, affirms that the barbarian invasions are ‘God´s judgement’ that come ‘in punishment for the faults of the Romans’ (poenaliter accidisse). It is the equivalent of the ‘plagues’ Moses used to blame the Pharaoh.

On 24 August 410, Alaric, king of the Visigoths, after besieging Rome for several weeks, entered the city by night through the Porta Salaria. It was a converse patrician, Proba Faltonia, of the Anician family, who, after sending her slaves to occupy the gate, had it surrendered to the enemy. The Visigoths were Christians, and the spiritual and ideological solidarity bore fruit. The Anicians, of whom Amianus Marcellinus (XVI, 8) says that they were reputed to be insatiable, were known as fanatics of the Catholic party. The sack of Rome that followed was described by Christian authors with kindly strokes. Alaric’s ‘clemency’ was praised. Georges Sorel asked: ‘Were the vanquished guilty?’ St Augustine says of the Visigothic leader, he was God’s envoy and the avenger of Christianity. Oretius says that only one senator died and that it was his fault (‘he had not made himself known’), and that it was enough for Christians to make the sign of the cross be respected, and so on. ‘Such daring lies, says Augustin Thierry, were later admitted as indisputable facts’ (Alaric).

Around 442, Quodvulteus, bishop of Carthage, claimed that the ravages of the Vandals were pure justice. In one of his sermons, he tried to console a faithful member who had complained about the devastation: ‘Yes, you tell me that the barbarian has taken everything from you… I see, I understand, I meditate: you, who lived in the sea, have been devoured by a bigger fish. Wait a little: an even bigger fish will come and devour the one who devours, despoil the one who despoils, take the one who takes… This plague that we are suffering today will not last forever: in truth, it is in the hands of the Almighty’. Finally, at the end of the 5th century, Salvianus of Marseilles affirms that ‘the Romans have suffered their sorrows by the just judgement of God’.

In the 2nd century, the City had been invaded by foreign cults. A temple to the Great Mother had been erected on the Palatine Hill, where fanatici officiated. Moral contagion did the rest. ‘Through the gap opened in the barrier that closes the horizon of terrestrial life, they were going to penetrate all sorts of chimaeras and superstitions, drawn from the inexhaustible reservoir of the Oriental imagination.’ (Bouché-Leclercq). These were the bacchanalia, the rites with mysteries, the Isiac cult, the cult of Mithra, and finally, Christianity. The words ‘The last of his family’ were written in the tombs more frequently. Pompey’s line had disappeared in the 2nd century, and also Augustus’ and Maecenas’ lines.

Rome was no longer Rome; all the rivers of the East flowed into the Tiber. It was only much later, in the Renaissance, that Petrarch (1304-1374) observed that the ‘black epoch’ (tenebrae) of Roman history had coincided with the era of Theodosius and Constantine; while in northern Europe, in the early 16th century, Erasmus (c. 1469-1536) claimed, although he called himself a ‘militiaman of Christ’, that the true barbarians of ancient times, the ‘real Goths’, had been the monks and scholastics of the Middle Ages.

‘All propaganda has to be popular and has to accommodate itself to the comprehension of the least intelligent of those whom it seeks to reach’.

—Hitler

The communism of antiquity, 5

by Alain de Benoist

Christian doctrine was a social revolution. It did not affirm for the first time that the soul existed (which would not have made it original), but that everyone had one identical at birth. The men of ancient culture, who were born into a religion because they were born into a fatherland, tended instead to think that by adopting a behaviour characterised by rigour and self-control they might succeed in forging a soul, but that this was a fate reserved undoubtedly for the best. The idea that all men could be gratified with it indifferently and simply by the fact of existing was shocking to them. On the contrary, Christianity maintained that everyone was born with a soul, which was equivalent to saying that men were born equal before God.

On the other hand, in its rejection of the world, Christianity presented itself as the heir of an old biblical tradition of hatred of the powerful, of the systematic exaltation of the ‘humble and the poor’ (anavim ébionim), whose triumph and revenge over wicked and proud civilizations had been announced by prophets and psalmists. In the Book of Enoch, widely disseminated in the first century in Christian circles (cited in the epistles of Jude XV, 4, and of Barnabas: XV), we read: ‘The Son of Man will raise kings and the powerful from their beds and the strong from their seats; he will break their strength… He will overthrow kings from their thrones and their power. He will make the mighty turn their faces away, and cover them with shame…’ (Enoch XLVI, 4-6).

Jeremiah takes pleasure in imagining the future victims in the form of animals for the slaughter: ‘Separate them, O Yahweh, like sheep for the slaughter, and reserve them for the day of slaughter’ (Jeremiah XII, 3). To the women of the powerful, whom he calls ‘cows of Bashan’ (Amos IV, I), Amos predicts: ‘Yahweh has sworn by his holiness: The days will come upon you when you will be lifted with hooks, and your descendants with fishing spears’ (IV, 2). The psalms outline the beginning of the class struggle, and the same spirit will inspire ‘the first groups of Christians and later the monastic orders’ (A. Causse, op. cit.). ‘In the end, there is only one theme in the Psalms,’ says Isidore Loeb, ‘which is the struggle of the poor against the wicked, and his final triumph thanks to the protection of God, who loves the one and hates the other’ (Littérature des pauvres dans la Bible).

The poor are always the victims of injustice. They are called the Humble, the Holy, the Just and the Pious. They are unfortunate, prey to all evils; they are sick, invalid, alone, abandoned, relegated to a valley of tears, they water their bread with tears, etc. But they bear their pain; they even seek it out because they know that such trials are necessary for their salvation, that the more they are humiliated, the more they will triumph, the more they suffer, the more they will one day see others suffer. As for the wicked, they are rich, and their wealth is always culpable.

They are happy, build cities, perform pre-eminent social functions, and command armies, but they will one day be punished in proportion as they dominate. ‘Such is the social ideal of Jewish prophecy,’ says Gerard Walter, ‘a kind of general levelling which will make all class distinctions disappear and lead to the creation of a uniform society from which all privileges of any kind will be banished. This egalitarian sentiment, carried to its ultimate limits, is linked to an irreducible animosity against the rich and the powerful, who will not be admitted into the future kingdom. The ideal humanity of the announced times will include all the just without distinction of creed or nationality’ (Les origines du communisme, Payot, 1931).

They are happy, build cities, perform pre-eminent social functions, and command armies, but they will one day be punished in proportion as they dominate. ‘Such is the social ideal of Jewish prophecy,’ says Gerard Walter, ‘a kind of general levelling which will make all class distinctions disappear and lead to the creation of a uniform society from which all privileges of any kind will be banished. This egalitarian sentiment, carried to its ultimate limits, is linked to an irreducible animosity against the rich and the powerful, who will not be admitted into the future kingdom. The ideal humanity of the announced times will include all the just without distinction of creed or nationality’ (Les origines du communisme, Payot, 1931).

The second book of the Sibylline Oracles paints a picture of humankind regenerating in a new Jerusalem under a strictly communist regime: ‘And the land will be common to all; there will be no more walls or frontiers. All will live in common and wealth will be useless. Then there will be no more poor or rich, no tyrants or slaves, no great or small, no kings or lords, but all will be equal’ (Or. Sib. II, 320-326).

Given this, it is easier to understand why Christianity initially seemed to the ancients to be a religion of slaves and heimatlos, a vehicle for a kind of ‘counterculture’ that only achieved success among the dissatisfied, the declassed, the envious and the revolutionaries avant la lettre: slaves, artisans, fullers, carders, shoemakers, single women, etc. Celsus describes the first Christian communities as ‘a mass of ignorant people and gullible women, recruited from the dregs of the people,’ and his adversaries hardly try to disabuse him on this point. Lactantius preaches equality in social conditions: ‘There is no equity where there is no equality’ (Inst. VII, 2). Under Heliogabalus, Calixtus, bishop of Rome, recommends that converts marry slaves.

Given this, it is easier to understand why Christianity initially seemed to the ancients to be a religion of slaves and heimatlos, a vehicle for a kind of ‘counterculture’ that only achieved success among the dissatisfied, the declassed, the envious and the revolutionaries avant la lettre: slaves, artisans, fullers, carders, shoemakers, single women, etc. Celsus describes the first Christian communities as ‘a mass of ignorant people and gullible women, recruited from the dregs of the people,’ and his adversaries hardly try to disabuse him on this point. Lactantius preaches equality in social conditions: ‘There is no equity where there is no equality’ (Inst. VII, 2). Under Heliogabalus, Calixtus, bishop of Rome, recommends that converts marry slaves.

For this reason, there is no idea more odious to the Christian than that of the fatherland: how can one serve both the land of one’s fathers and the Father who is in heaven? Salvation does not depend on birth, belonging to a city, or the seniority of one’s lineage but exclusively on respect for dogmas. From then on, it is enough to distinguish believers from unbelievers, and all other boundaries must disappear. Paul insists on this: ‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither male nor female…’ Hermas, who enjoyed great authority in Rome, condemns the converts to perpetual exile: ‘You servants of God live in a foreign land. Your city is very far from this one’ (Sim. I, I).

Such a disposition of spirit explains the Roman reaction. Celsus, a patriot concerned about the health of the State, who sensed the weakening of the Imperium and the decline of civic feeling that the triumph of Christian egalitarianism could provoke, begins his True Discourse with these words: ‘A new race of men born yesterday, without homeland or traditions, united against all religious and civil institutions, persecuted by justice, accused of infamy by all and who glory in this common execration: that is what Christians are. Factious men who pretend to make a separate ranch and separate themselves from common society.’ And Tacitus, who says that they were detested for their ‘abominations’ (flagitia), accuses them of the crime of ‘hatred of the human race.’ ‘As soon as it was suppressed,’ he says, ‘this execrable superstition was once again breaking out not only in Judea, the cradle of the plague, but in Rome itself, where all the horrors and infamies that exist flow from all sides and are believed…’

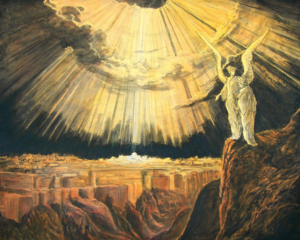

The imperial principle is at this time the instrument of a conception of the world carried out as a vast project. Thanks to it, the Pax Romana reigns in an ordered world. Filled with admiration, Horace exclaims: ‘The ox wanders safely through the fields fertile by Ceres and Abundance, while sailors everywhere plogh the peaceful seas.’ In Halicarnassus, a tripartite inscription in honour of Augustus proclaims: ‘Cities flourish amid order, concord and wealth.’ But for the early Christians the pagan State is the work of Satan. The Empire, the supreme symbol of a proud force, is nothing but arrogance worthy of ridicule. The harmonious Roman society is declared without exception guilty, for its resistance to monotheistic demands, traditions and way of life, are so many offences against the laws of heavenly socialism. And as guilty, it must be punished; that is, destroyed. Like a lengthy complaint, the Christian literature of the first two centuries breathes out its rosary of anathemas. With feverish impatience the apostles preach the ‘hour of vengeance,’ ‘so that all things which are written may be fulfilled’ (Luke XXI, 22). As the Fathers of the Church did after them, they announce the imminence of revenge, of the ‘great night’ when everything will be turned upside down. The Epistle of James contains a call to class struggle: ‘Come now, you rich people! Weep and howl for the misery that will come upon you. Your riches are corrupted and your clothes are moth-eaten’ (V,1-2).

James, who has read the Book of Enoch, predicts terrible tortures for the rich and the pagans. He imagines the final judgment as a ‘knock to the throat,’ ‘a kind of immense slaughterhouse to which thousands of the well-off, fat and splendid, and with all their wealth on them, will be dragged. He is joy at seeing them go one by one, returning their ill-gotten gains before feeding with their fat the formidable carnage he glimpses in his dreams’ (Gérard Walter, op. cit.). Above all, he accuses the rich of deicide: ‘You condemned and killed the Just One.’ (V, 6.) This thesis, which makes Jesus the victim, not of a people, but of a class, will soon become popular. Tertullian writes: ‘The time is ripe for Rome to end up in flames. She will receive the reward her works deserve’ (On Prayer, 5).

The Book of Daniel, written between 167 and 165 b.c.e., and the Book of Revelation are the two great sources from which this holy fury draws. St. Hippolytus (c. 170-235), in his Commentary on Daniel, places the end of Rome around the year 500 and attributes it to the rise of democracies: ‘The toes of the statue in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream represent the coming democracies, which will separate from each other like the ten toes of the statue, in which iron will be mixed with clay.’ Around 407, St. Jerome, in another Commentary on Daniel, defines the end of the world as ‘the time when the kingdom of the Romans will be destroyed.’ Other authors repeat these prophecies: Eusebius, Apollinaris and Methodius of Olympus. The revolutionary ardour against Rome, the ‘accursed city,’ ‘new Babylon,’ and ‘great harlot’ knows no bounds. The city is the last avatar of Leviathan and Behemoth.

In all these apocalypses, sibylline mysteries and double-meaning prophecies, in all this mental trepidation, hypersensitive to ‘symbols’ and ‘signs,’ in all this psalm-like literature, we find more imprecations than would have been necessary to warm the spirits, shake the imaginations and even arm still hesitant hands. This explains the accusations that followed the burning of Rome in the year 64.

Deuteronomy ordered the services of God to slaughter unbelieving populations and burn their cities in honour of Yahweh, and Jesus repeated the image: ‘He who does not abide in me will be thrown out like a branch that withers, and is gathered and thrown into the fire and is burned’ (John XV, 6). And indeed, from Rome to the bonfires of the Inquisition, much will burn. Sacred pyromania will be exercised without respite. ‘This idea (that the world of the impious will be destroyed by fire),’ says Bouché-Leclercq, ‘had been received by Christians from Jewish seers, from those prophets and sibilants who invoked lightning as quickly as a torch, iron as quickly as fire on the cities and peoples hostile to Israel. Never has the imagination burned so much as in the prophecies of Isaiah and Ezekiel, the richest collection of anathemas that religious literature has ever produced.’

‘In this opinion of a general fire,’ adds Gibbon, ‘the faith of Christians came to coincide with the Eastern tradition… The Christian, who based his belief not so much on the fallacious arguments of reason as on the authority of tradition and the interpretation of Scripture, awaited the event with terror and confidence, was sure of its ineluctable imminence. As this solemn idea permanently occupied his mind, he regarded all the disasters that befell the Empire as so many infallible symptoms of the agony of the world.

‘If today I stand here as a revolutionary, it is as a revolutionary against the Revolution’.

—Hitler

I listened to a couple of black guys’ recent interview with Derek Lambert and found it very instructive.

What I loved about the interview was a family anecdote. In trying to reason gently with his Christian mom, rather than giving her the exegetical spiel he mentions on his MythVision podcasts, Derek compared the NT to the tale of Odysseus: the religion of the ancient world for white people. At one point, Derek mentioned that the Greek Gods were absolutely beautiful physically (which is just what I’ve tried to convey on this blog since the site’s earlier incarnations)! So admirably did he summarise the adventures of Odysseus that, in a soliloquy, I said to myself: This segment could very well have come from the lips of an NS man trying to raise Aryan children!

Indeed, Derek’s words about The Odyssey are the best introduction to the ethos of Homer’s epic poem that I know of. Alas, although in that interview Derek spoke eloquently about the dishonesty of Christian apologists, as a good neochristian he doesn’t tolerate ‘racists’, ‘homophobes’ and ‘misogynists’ (see here why we put quotation marks around these words).

The communism of antiquity, 4

by Alain de Benoist

The ancients believed in the unity of the world, in the dialectical intimacy of man with nature. Their natural philosophy was dominated by the ideas of becoming and alternation. The Greeks equated ethics with aesthetics, the kalôn with the agathôn, the good with beauty, and Renan rightly wrote: ‘A system in which the Venus de Milo is only an idol is a false system, or at least a partial one, because beauty is worth almost as much as goodness and truth. With such ideas, a decline in art is inevitable.’ (Les apótres, p. 372). The ‘new man’ of Christianity professed a very different vision of things. He carried within himself a conflict, not the everyday one that forms the fabric of life, but an eschatological, absolute conflict: the divorce from the world.

The ancients believed in the unity of the world, in the dialectical intimacy of man with nature. Their natural philosophy was dominated by the ideas of becoming and alternation. The Greeks equated ethics with aesthetics, the kalôn with the agathôn, the good with beauty, and Renan rightly wrote: ‘A system in which the Venus de Milo is only an idol is a false system, or at least a partial one, because beauty is worth almost as much as goodness and truth. With such ideas, a decline in art is inevitable.’ (Les apótres, p. 372). The ‘new man’ of Christianity professed a very different vision of things. He carried within himself a conflict, not the everyday one that forms the fabric of life, but an eschatological, absolute conflict: the divorce from the world.

Early Christianity extends the messianic idea present in Judaism in an exacerbated form, due to a millennial expectation. In the words attributed to Jesus we find literal quotations from the visions of the Book of Enoch. For the first Christians, the world, a mere stage, a vale of tears, a place of unbearable difficulties and tensions, needed compensation, a radiant vision that would justify (morally speaking) the impotence of here below. That is why the earth appears as the field on which the forces of Evil and Good, the prince of this world and the heavenly Father, those possessed by the devil and the sons of God, confront each other: ‘And this is the victory that has overcome the world: our faith’ (I John V, 4). The idea that the world belongs to Evil, later characteristic of certain Gnostics (the Manicheans), appears frequently in the first writings of Christianity. Jesus himself affirmed: ‘I do not pray for the world…, as I am not of the world’ (John XVII, 9-14). St. John insists: ‘Do not love the world, nor the things that are in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life, is not of the Father but is of the world.’ (I John II, 15-16.) ‘Do not be surprised if the world hates you.’ (Ibid. III,13). ‘We know that we are of God, and the whole world lies in the power of the evil one.’ (Ibid. V, 19.) Later, the Rule of St. Benedict will state as a precept that monks must ‘make themselves strangers to the things of the world’ (A saeculi actius se facere alienum). In the Imitation of Christ we read: ‘The truly wise man is he who, in order to gain Christ, considers all the things of the earth as rubbish and dung.’ (I, 3, 5).

Early Christianity extends the messianic idea present in Judaism in an exacerbated form, due to a millennial expectation. In the words attributed to Jesus we find literal quotations from the visions of the Book of Enoch. For the first Christians, the world, a mere stage, a vale of tears, a place of unbearable difficulties and tensions, needed compensation, a radiant vision that would justify (morally speaking) the impotence of here below. That is why the earth appears as the field on which the forces of Evil and Good, the prince of this world and the heavenly Father, those possessed by the devil and the sons of God, confront each other: ‘And this is the victory that has overcome the world: our faith’ (I John V, 4). The idea that the world belongs to Evil, later characteristic of certain Gnostics (the Manicheans), appears frequently in the first writings of Christianity. Jesus himself affirmed: ‘I do not pray for the world…, as I am not of the world’ (John XVII, 9-14). St. John insists: ‘Do not love the world, nor the things that are in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life, is not of the Father but is of the world.’ (I John II, 15-16.) ‘Do not be surprised if the world hates you.’ (Ibid. III,13). ‘We know that we are of God, and the whole world lies in the power of the evil one.’ (Ibid. V, 19.) Later, the Rule of St. Benedict will state as a precept that monks must ‘make themselves strangers to the things of the world’ (A saeculi actius se facere alienum). In the Imitation of Christ we read: ‘The truly wise man is he who, in order to gain Christ, considers all the things of the earth as rubbish and dung.’ (I, 3, 5).

In the midst of the great artistic and literary renaissance of the first two centuries, Christians, as outsiders who pleased to be so, remained indifferent or, more often, hostile. Biblical aesthetics rejected the representation of forms, the harmony of lines and volumes; consequently, they had only a disdainful look on the statues that adorned squares and monuments. For the rest, everything was an object of hatred. The colonnades of temples and covered walks, the gardens with their fountains and domestic altars where a sacred flame flickered, the rich mansions, the uniforms of the legions, the villas, the ships, the roads, the works, the conquests, the ideas: everywhere the Christian saw the mark of the Beast. The Fathers of the Church condemned not only luxury, but also any profane work of art, colourful clothing, musical instruments, white bread, foreign wines, feather pillows (had not Jacob rested his head on a stone?) and even the custom of cutting one’s beard, in which Tertullian sees ‘a lie against one´s own face’ and an impious attempt to improve the work of the Creator.

The rejection of the world became even more radical among the early Christians because they were convinced that the Parousia (the return of Jesus Christ at the end of time) was going to take place immediately. It was Jesus himself who had promised it to them: ‘Assuredly, I say to you, some who are standing here will not taste death until they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom.’ (Matthew XVI, 28). ‘Assuredly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have happened.’ (Matthew XXIV, 34). In view of this, they repeated the good news more and more. But the end of all things is at hand (I Peter IV, 7). ‘It is the last time’ (I John II, 18). Paul returns again and again to this idea. To the Hebrews: ‘Therefore cast not away your confidence, which has great reward… For yet a little while, and He that shall come will come, and will not delay’ (Hebrews X, 35-37). ‘Not forsaking the assembling of ourselves together… but exhorting one another, and so much the more as you see the day approaching’ (Ibid., X, 25). To the Thessalonians: ‘Stand firm, for the coming of the Lord is at hand.’ To the Corinthians: ‘Brothers, the time is short; therefore let those who have wives be as though they had none…’ (I Cor. VII, 29). To the Philippians: ‘The Lord is near. Do not be anxious about anything…’ (Phil. IV, 5 and 6).

In his dialogue with Trypho, Justin affirms that Christians will soon be gathered in Jerusalem, and that it will be for a thousand years (LXXX – LXXXII). In the second century, the Phrygian Montanus declares that he foresees the imminence of the end of the world. In Pontus, Christian peasants abandon their fields to await the day of judgment. Tertullian prays pro mora fines, ‘that the end may be delayed.’ But time passed and nothing happened. Generations disappeared, one after another, without having seen the glorious advent; and faced with the continual delay of its eschatological hopes, the Church, giving proof of prudence, ended by resigning itself to placing the Parousia in an undetermined ‘beyond.’ Today only Jehovah’s Witnesses repeat on a fixed date: ‘Next year in the Jerusalem of heaven.’

‘The doom of a nation can be averted only by a storm of flowing passion, but only those who are passionate themselves can arouse passion in others’.

—Hitler

Editor’s note: I feel compelled to include this recent communication from our friend Gaedhal because on this site, in promoting the work of Richard Miller, I have been using Derek Lambert’s interviews of Miller (Derek vlogs at MythVision Podcast). Miller’s New Testament scholarship is impeccable, but young Derek still has much to learn from the older folks. Gaedhal wrote:

Editor’s note: I feel compelled to include this recent communication from our friend Gaedhal because on this site, in promoting the work of Richard Miller, I have been using Derek Lambert’s interviews of Miller (Derek vlogs at MythVision Podcast). Miller’s New Testament scholarship is impeccable, but young Derek still has much to learn from the older folks. Gaedhal wrote:

______ 卐 ______

I include Derek from MythVision on this thread, although I removed him over the Robert Price thing. The Zionist video he released with his ex-military father in the wake of October 7th removed any doubt in my mind that this was the correct choice. Also, on MythVision, some theisms—i.e. The Orthodox Judaism of the likes of Tovia Singer—seem to be more equal than others. I think that even Kipp Davis—arguably an “apologist enabler” himself—recently called Tova Singer’s “scholarship” deplorable. I like Tovia, and, indeed, I learn a lot of Hebrew vocabulary from him, as he can slip seamlessly betwixt English and Ashkenzic Hebrew. Tovia will regularly, from memory, quote the Tenakh in Hebrew from memory. Although I like Tovia, nevertheless, orthodox Judaism is every bit as false and harmful as every other theism.

My view is that all apologists are cynical conmen. I would love to believe otherwise, though. I would love to believe that they were simply the other side of the argument; that there were good sensible reasons to believe in Classical Theism, even if I personally disbelieved in it; that there were good sensible reasons to believe in Christianity, even if I personally disbelieved in it.

However, this is not the case. Of all the theisms, Classical Theism is the most untenable. Of all the revealed religions, the claims of Christianity are extremely untennable indeed. At best, there is no better reason to believe that an Undead Jesus Christ floated off into the sky than that Mohommed flew to Jerusalem on a wingéd horse.

As Pocket locker 86, linked here, points out: there is no honest way to defend something that is untrue.

Thus the grifters, psychotics, psychopaths, morons and fraud-artists who make up the rogues gallery of Christian apologists. I do not, in the slightest, hate Christians or theists. Indeed, I remain a secular Catholic who is uncomfortable with the label: atheist.

Now, to be clear, one can be intelligent, empathetic, sincere, etc. and have a sincere religious faith. However, in my view, the field of apologetics itself being intrinsically fraudulent, it is impossible to be an honest apologist. An honest apologist is, to me at least, an oxymoron.

The fake credentials of some Christian apologists, such as “Doctor” Stephen Boyce—billed as a doctor by MythVision, in its description, at the time of writing!

I linked to Chrissy Hansen’s article questioning Boyce’s doctorate and my comment was deleted.

Pocket locker 86 would say: “whose side are you on!” i.e., are you on the side of us counter-apologists who wish to expose scam artists like Boyce, or are you on the side of the scam artists who are trying to conceal their scam?

And this brings me to another point that Pocket Locker 86 points out: Apologists will only pretend to be your friend, and will only agree to go on your channel, if you pull your punches, and play nice with them. If you point out that their credentials are at best dubious, they will probably demand that such a comment be deleted.

It is interesting that Hansen, a transgender Norse polytheist, has retreated from the limelight following the election of Trump.

to thank the sponsors

of this site in 2024:

B. T.

W. R.

T. J. M.

M. M.

R. W.

J. L.

and

B. P.