Criminal History, 192

For the context of these translations click here.

PDFs of entries 1-183 (several of Karlheinz Deschner’s

books abridged into two) can be read here and here.

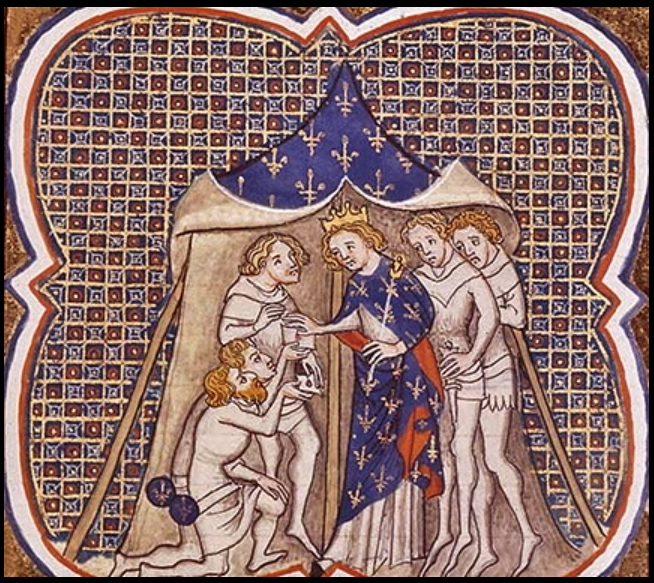

Charles the Fat receives the offer of kingship from two West Francian ambassadors.

Bishop Liutward of Vercelli – celebrated and fired

This man, a Swabian from (according to hostile sources) a very lowly family, was a monk at Reichenau, a monastery that only accepted nobles in the 10th century, and Charles’ chancellor during his Swabian reign. The up-and-comer took advantage of his high patron’s career. He became bishop of Vercelli in 879/880, Charles’ arch-chancellor and arch-chaplain, his most influential advisor and finally ‘more honoured and feared by all than the emperor’ (Annales Fuldenses). After all, the clerical upstart had an almost unimaginable wealth and took great care of his relatives. Brother Chadolt became Bishop of Novara in 882, and a nephew with the same name Liutward became Bishop of Como a little later.

As a result of his progressive hereditary illness, the emperor increasingly left governance to Liutward. In the end, he held most of the strings in his hands, led all important delegations and, in particular, organised all negotiations with the Pope from the very beginning. In short, the bishop stood as ‘the all-powerful minister next to the weak ruler’, was ‘virtually the head of Charles III’s policy’ (Schur) and ‘the key figure of his reign’ (Fleckenstein).

Gradually, however, Bishop Liutward increasingly incurred the wrath of wider circles. Not only because he sought to oust everyone from the emperor’s side, not only through his concessions to the Normans in Elsloo, where he is said to have been bribed by them but also through his greed, his nepotism and his infamous clan politics in general, whereby he had girls from the noblest families from Swabia and Italy stolen to give them to relatives as wives. He even ordered a break-in at the nunnery of St Salvatore in Brescia to extract a daughter of Margrave Unruoch of Friuli for a nephew, a granddaughter of Louis the Pious on her mother’s side: a splendid match. ‘But the nuns of this place turned to prayer and asked the Lord to avenge the dishonour inflicted on the holy place; their request was immediately granted. The one who wanted to consummate the marriage with the girl in the usual way died that night and the girl remained untouched (intacta). This was reported to a nun from the above-mentioned convent’ (Annales Fuldenses).

The abrupt death of the bishop’s nephew on the night of the bride seemed too little for the uncle of the bridegroom, Margrave Berengar of Friuli. He hurried to Vercelli, ‘and once there, he stole as much of the bishop´s belongings as he wished’. Not enough, Liutward was also accused of ‘heresy’, namely ‘belittling our Saviour by claiming that He is One through the unity of substance, not of person’ (Annales Fuldenses). He was also accused of adultery, even with the empress herself—all of which was publicly brought up in the summer of 887 at the Imperial Diet in Kirchen (near Lörrach).

Charles the Fat, however, was not only comfortable and unambitious by nature, he was also ill, physically and perhaps mentally. In the spring, in the Palatinate of Bodmann, his favoured region of Lake Constance, he had his head ‘incised in pain’ (incisionem): a mistranslation, it is now thought, not a trepanation, less dramatic.

Nevertheless, the emperor was almost incapable of ruling (admittedly the fate of many rulers). And in this fatal situation, he also exposed his first man to general anger and disappointment. Without any dialogue with Liutward, he stripped him of many fiefs ‘and drove him out of the palace in disgrace as a heretic hated by all. But the latter went to Baiem to Arnulf and discussed with him how he could rob the emperor of his rule’.