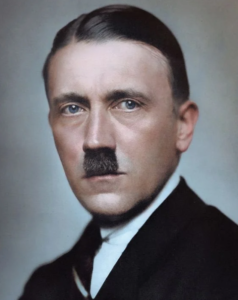

Hitler was well aware of the industrial strength of the British Empire and the United States, but in his view the struggle against the Anglo-Americans during the First World War was not decided solely by material factors. His vision of international politics was essentially human-centred. On Hitler’s reading, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had been an epic demographic contest which the German Empire had spectacularly lost. She had failed to provide an outlet for her excess population either through economic or through territorial expansion, with the result that millions of Germans had emigrated. Meanwhile, her enemies built up huge empires which they could parlay into strength on the European battlefield. Hitler lamented ‘that the Entente sent alien auxiliary peoples to bleed to death on European battlefields’. He had personal experience of this, having confronted (British) Indian troops in 1915 and (French) Algerian Zouaves in 1918. Hitler’s anxiety deepened on beholding the Africans and Moroccans who formed part of the French occupation forces in the 1920s. He accused France of ‘only waiting for the warm season to throw an army of 800-900,000 blacks into [our] country to complete the work of the total subjugation and violation of Germany’. Hitler’s concern was thus not only racial, but strategic: that France would use the human reserves of Africa to oppress Germany, a weapon no longer available to Germany as she had lost her much smaller overseas empire as a result of the war.

The main threat posed by the European empires, however, was not the deployment of men from the ‘subject races’, but from the white settler colonies. Some of the most formidable British troops on the western front had come from Canada, Australia and New Zealand. They were numerous, well fed, fit, highly motivated, and often extremely violent. Worse still was the fact that the Germans whom the Reich had exported in the nineteenth century for want of land to feed them had come back to fight against her as American soldiers during the war. In later speeches, as we shall see, Hitler repeatedly came back to the moment he had encountered his first American prisoners. The emigration question was the subject of his second known major speech in September 1919, and it also underlay his next disquisition, which was on the internal colonization of Germany. His thoughts on that subject so impressed his sponsor Captain Mayr that he announced his intention ‘to launch this official report abridged or in full in the press in a suitable manner’. Emigration was part of daily life in post-war Germany, so much so that a whole newspaper in Munich, Der Auswanderer (‘The Emigrant’), was devoted to the topic.

That said, although contemporary concern with the emigration issue went well beyond Hitler, it does not seem to have enjoyed a particular salience in the broader inquest into the war. It thus represents his distinctive contribution to the debate on German revival and one of the most important lessons he drew from the war. Henceforth the emigration question, and the associated American problem, lay at the very heart of Hitler’s thinking.

2 replies on “Hitler, 10”

I can hardly imagine any politician here concerned about Americans leaving in mass due to the incoming collapse of the country.

But how can we expect that when we live in a multicultural, racially diverse cesspool?

Hitler was remarkable by also wanting to create a German revival, despite the formidable enemies around and challenges.

It’s a great shame that the entire 19th century was wasted on petty nationalism and sycophantic subservience to the whims of Royal Families. If the white nations of Europe had viewed themselves as one people with a shared destiny, they could have exterminated every non-white population. Christianity, of course, was the biggest obstacle to this. By all rights, once Darwin made his discovery, all religions should have been abandoned. It is unnerving to think that adherents of false beliefs can maintain their delusion by simply ignoring the evidence against them. It’s terrifying, the power of unyielding denial.