Or:

How the Woke monster originated

The chapter ‘Revolution, 1076 Cambrai’ begins by explaining how the Catholic Church decided to expand the vow of celibacy, which already existed for alienated monks, to all priests.

This, from my point of view, was a step that led to the abuse of children and pubescents in the Church throughout the next millennium, as now even the clergy could not marry, burning themselves in celibacy and masturbation. Such an aberrant step has to do with the Christian view of the human soul, which assumes that lust doesn’t exist in a pure soul, but that we simply indulge in impure thoughts, concupiscence.

A millennium later such a view of the human soul would become, in secularised form, in the trans movement that assumes that we are not sexualised animals but that we can simply ‘choose’ our sexes. In the following pages, Tom Holland mentions a milestone in the mentality of Europeans regarding the increasing power of the Church:

‘The Pope is permitted to depose emperors.’ This proposition, one of a number of theses on papal authority drawn up for Gregory’s private use in March 1075, had shown him more than braced for the inevitable blow-back. No pope before had ever claimed such a licence; but neither, of course, had any pope dared to challenge imperial authority with such unapologetic directness. Gregory, by laying claim to the sole leadership of the Christian people, and trampling down long-standing royal prerogatives, was offending Henry IV grievously. Heir to a long line of emperors who had never hesitated to depose troublesome popes, the young king acted with the self-assurance of a man supremely confident that both right and tradition were on his side. Early in 1076, when he summoned a conference of imperial bishops to the German city of Worms, the assembled clerics knew exactly what was expected of them. The election of Hildebrand, so they ruled, had been invalid. No sooner had this decision been reached than Henry’s scribes were reaching for their quills. ‘Let another sit upon Saint Peter’s throne.’ The message to Gregory in Rome could not have been blunter. ‘Step down, step down!’

But Gregory also had a talent for bluntness. Brought the command to abdicate, he not only refused, but promptly raised the stakes. Speaking from the Lateran, he declared that Henry was ‘bound with the chain of anathema’ and excommunicated from the Church. His subjects were absolved of all their oaths of loyalty to him. Henry himself, as a tyrant and an enemy of God, was deposed. The impact of this pronouncement proved devastating. Henry’s authority went into meltdown. Numerous of his princely vassals, hungry for the opportunity that his excommunication had given them, set to dismembering his kingdom. By the end of the year, Henry found himself cornered. To such straits was his authority reduced that he settled on a desperate gambit. Crossing the Alps in the dead of winter, he headed for Canossa, a castle in the northern Apennines where he knew that Gregory was staying. For three days, ‘barefoot, and clad in wool’, the heir of Constantine and Charlemagne stood shivering before the gates of the castle’s innermost wall. Finally, ordering the gates unbarred, and summoning Henry into his presence, Gregory absolved the penitent with a kiss. ‘The King of Rome, rather than being honoured as a universal monarch, had been treated instead as merely a human being—a creature moulded out of clay.’

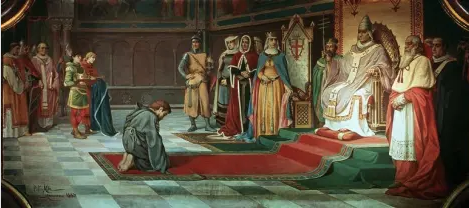

Henry IV, King of Germany from 1054 to 1105, King of Italy and Burgundy from 1056 to 1105, and Duke of Bavaria begging forgiveness of Pope Gregory VII at Canossa, the castle of the Countess Matilda, 1077.

The shock was seismic. That Henry had soon reneged on his promises, capturing Rome in 1084 and forcing his great enemy to flee the city, had done nothing to lessen the impact of Gregory’s papacy on the mass of the Christian people. For the first time, public affairs in the Latin West had an audience that spanned every region, and every social class. ‘What else is talked about even in the women’s spinning-rooms and the artisans’ workshops?’…

The humiliation of Henry IV had made visible a great and awesome prize. The dream of Gregory and his fellow reformers—of a Church rendered decisively distinct from the dimension of the earthly, from top to bottom, from palace to meanest village—no longer appeared a fantasy, but eminently realisable. A celibate clergy, once disentangled from the snares and meshes of the fallen world, would then be better fitted to serve the Christian people as a model of purity, and bring them to God…

Nevertheless, deep though the roots of Gregory’s reformatio lay in the soil of Christian teaching, the flower was indeed something new. The concept of the ‘secular’, first planted by Augustine, and tended by Columbanus, had attained a spectacular bloom. Gregory and his fellow reformers did not invent the distinction between religio and the saeculum, between the sacred and the profane; but they did render it something fundamental to the future of the West, ‘for the first time and permanently’. A decisive moment…

It was no longer enough for Gregory and his fellow reformers that individual sinners, or even great monasteries, be consecrated to the dimension of religio. The entire sweep of the Christian world required an identical consecration. That sins should be washed away; the mighty put down from their seats; the entire world reordered in obedience to a conception of purity as militant as it was demanding: here was a manifesto that had resulted in a Caesar humbling himself before a pope. ‘Any custom, no matter how venerable, no matter how commonplace, must yield utterly to truth—and, if it is contrary to truth, be abolished.’ So Gregory had written. Nova consilia, he had called his teachings—‘new counsels’.

A model of reformatio had triumphed that, reverberating down the centuries, would come to shake many a monarchy, and prompt many a visionary to dream that society might be born anew. The earthquake would reach very far, and the aftershocks be many. The Latin West had been given its primal taste of revolution. [pages 227-231]